Indirect tax system in India is still fraught with complexities and a cascading burden for the industry. Goods and Services Tax (GST) — aims to simplify the tax structure (more than VAT), eliminate any cascading effect, increase transparency, and boost government’s tax revenue. The NDA government is serious about implementing GST; many states have agreed and negotiations are going on with the rest. GST will bring significant gains to companies (tax credit benefit across the value chain) along with the advantages of a simple tax structure. GST will facilitate fiscal consolidation because of wider coverage and higher compliance. The flip side is that taxing consumption – which is the basis of GST – could dampen demand in case the burden on the consumer proves excessive, at least in the short term, until competitive forces even things out. The inflationary impact of GST will be based on the rate. While the form of GST may be debated (minimal exemption will bring in the best results), its introduction is vital. GST rollout is realistically possible from April 2016.

Why does India need GST so desperately?

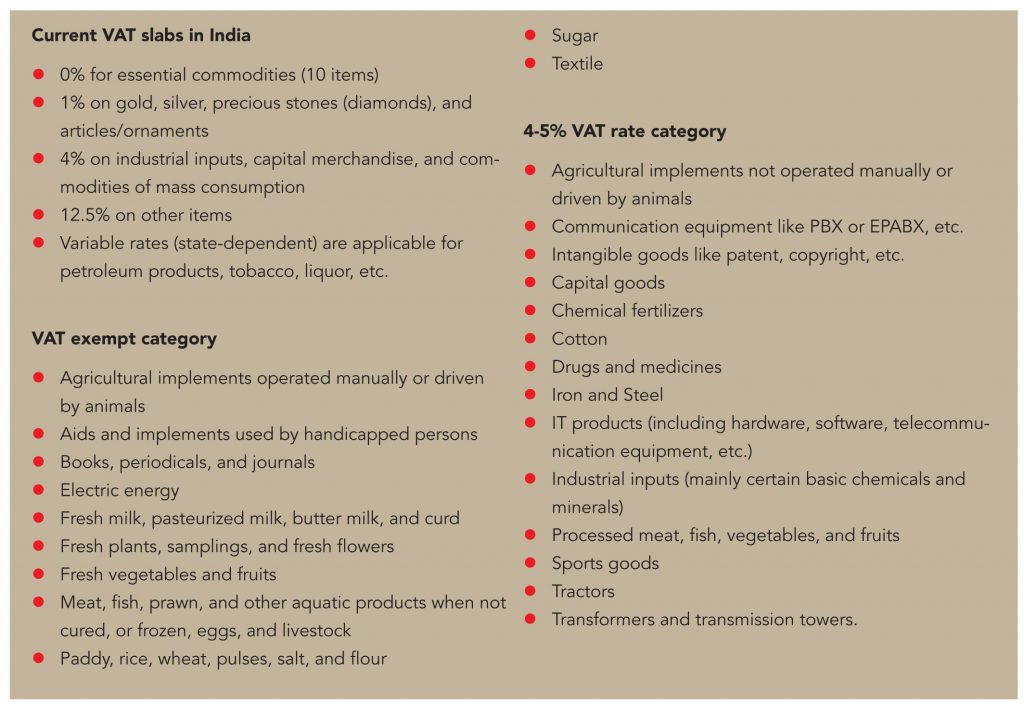

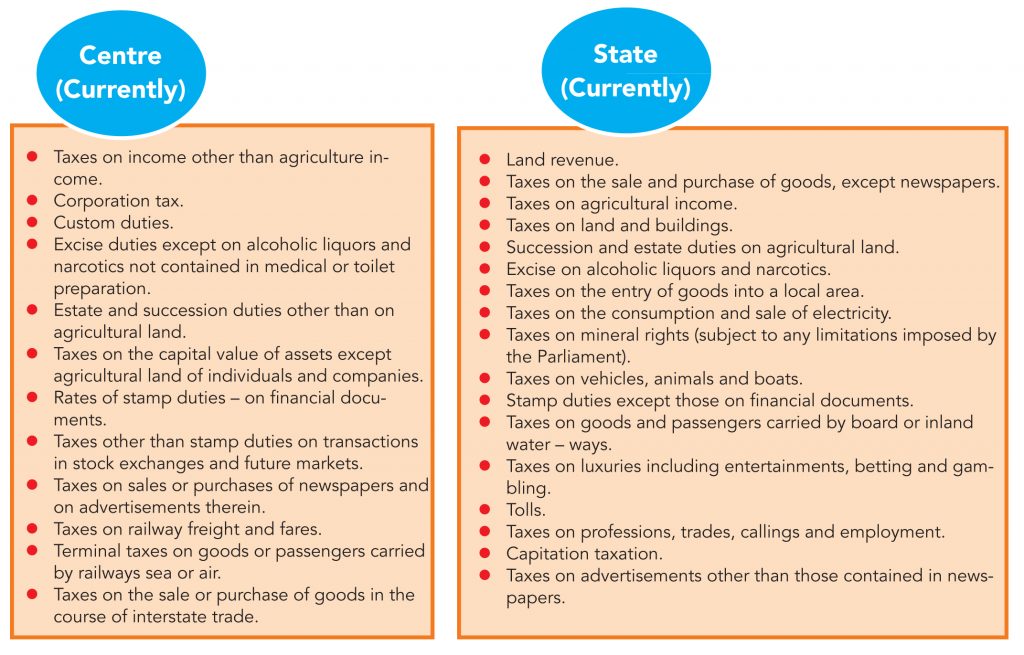

India has a very complex, multi-layered and highly inefficient tax structure, which stems from its federal structure — the centre and state both charge multiple taxes at different stages of the supply chain. A partial solution came in the form of VAT, but it did not iron out most of the inefficiencies of the system. GST will alter India’s tax landscape quite dramatically.

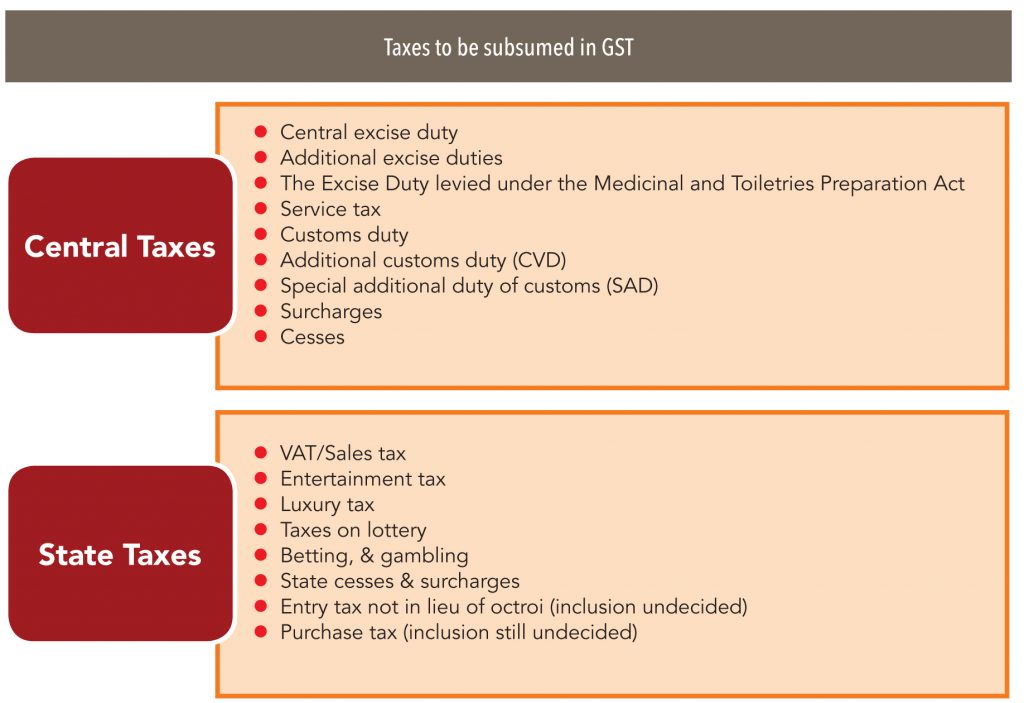

Under GST, all multiple taxes (or most of them at least) will be merged under one unified tax rate and the centre and state governments will charge single tax rate as compared to a host of taxes charged in the current regime. After the initial hiccups,this will simplify tax administration and collection to a huge extent for both the central and state governments. GST is expected to change India’s tax structure permanently and for the better — taxation will switch to the ‘destination principle’. It will broaden the tax base significantly, provided minimum exemptions are given. It will help build a common India-wide market across the country instead of the state-specific many markets that exist now and reduce compliance costs. Businesses will be able to take logical decisions based on profitability and economics, rather than illogical ones based on tax concerns.

However, despite all the known positives, GST is a politically charged subject — states fear losing their autonomy over taxation and manufacturing and exporting states fear a loss of revenue. The immediate tangible result of GST implementation is likely to be higher prices for consumers, which may not go down well for obvious reason; it will eventually indirectly help the end-consumers because industries may pass on the benefit with time and the government may lower direct taxes as revenues from indirect taxes rise.

When VAT was implemented, there was probably not a single trade and industry segment that did not register some kind of protest with the government.The most vociferous protests were from the trader lobby — more than 100,000 traders from all over the country converged on the Ramlila grounds in Delhi (in 2003) to protest the introduction of VAT. While ostentatiously their reasons for the protests were the possibility of harassment by tax inspectors and the need to maintain ‘pucca’ records, which they moaned were ‘cumbersome’ and would lead to harassment, even then, the real reason was believed to be different — under VAT they found less scope for tax evasion. GST will probably fare better as far as the trade and industry segment is concerned, because unlike VAT, which only partially solved problems while sometimes creating fresh ones, GST is actually expected

to make things far easier for the business community.

Following the success of indirect tax reform in the form of VAT, the central government is now focused on introducing another big reform in the form of GST (Goods and Service tax). GST was proposed in the FY08 budget and its implementation deadline was set at April 2010. Stiff resistance erupted from BJP-ruled states while Congress-ruled states were in favour. Now that the BJP-led NDA government is at the centre, GST should see the light of day. While states are wary of loss of fiscal autonomy and revenues because of GST implementation, the central government believes its introduction will bring revenue gain, fiscal consolidation, and higher GDP. Discussions are underway between the centre and state governments to arrive at a neutral path ensuring gains for the exchequer (centre/states), businesses, consumers, and the economy as a whole.

VAT was good; GST is the next step

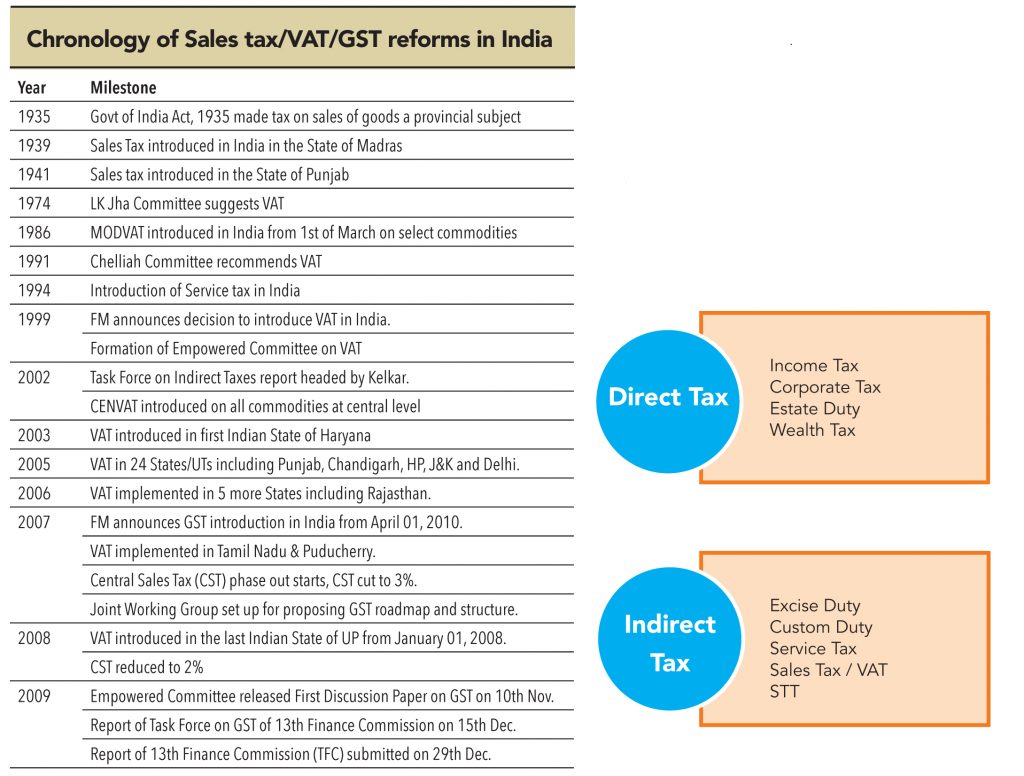

Before VAT was introduced, the tax structure suffered from multiple taxation, a cascading effect, and varying tax rates across states and commodities. There existed ten tax rates across the states causing poor compliance and excessive tax evasion. The shift from central excise duty to VAT began in the form of MODVAT (modified VAT) for select commodities. When this was extended to all commodities it was termed CENVAT (Central VAT) in 2002-03. Statelevel VAT was fully implemented in 2008. Just as GST is facing resistance now, when VAT was being implemented, states had resisted fearing revenue loss and loss of fiscal autonomy (sales-tax formed the largest source of revenue for states). It took 10 years from initiating the discussion to full implementation of state-level VAT — for GST, it has been 6 years since discussions have been initiated.

Revenue impact of VAT: Revenue compensation to states was based on the loss over and above the agreed loss due to VAT implementation by the states, distributed monthly. Total compensation to states for 3-years stood at Rs 132bn (100% of loss for FY06, 75% of loss for FY07, and 50% for FY08). Revenue growth of the VAT implementing states rose from 13.8% in FY06 to 21% in FY07 (as per government data). Based on a detailed study of VAT-implementing states, no revenue loss from indirect tax was found (few major states benefited along with many minor states) and direct tax revenue responded positively. However, due to large-scale tax evasion because of poor administration, benefits from VAT are limited.

Shortcomings of VAT: Certain taxes (such as surcharges,

service tax, entertainment tax) are outside the purview of VAT at the centre and state level, causing cascading problems. Weak tax administration by the states leads to tax evasion – limiting the benefits of VAT. Manufacturers are not able to attain the benefits from a comprehensive input tax and service tax set-off.

In GST, both the cascading effects of CENVAT and service tax are removed because it provides a ‘set-off’, and a continuous chain of set-off from the original producer and service provider up to the retailer is established, which reduces the burden of all cascading effects. This is the essence of GST, and this is why GST is not simply VAT plus service tax but an improvement over the previous system of VAT and disjointed service tax.

It is believed (not certain) that GST at centre and state levels will give more relief to industry, trade, agriculture, and consumers through a more comprehensive and wider coverage, higher tax set-offs (for input and service), inclusion of various taxes in GST, and phasing out of CST. If implemented with the calibrated tax rate and adequate state compensations, GST may bring in higher tax gain for both centre and states by way of higher coverage (base) and compliance. Thus, it benefits the state governments, central government, industry, trade, agriculture participants, and consumers.

Structure of GST

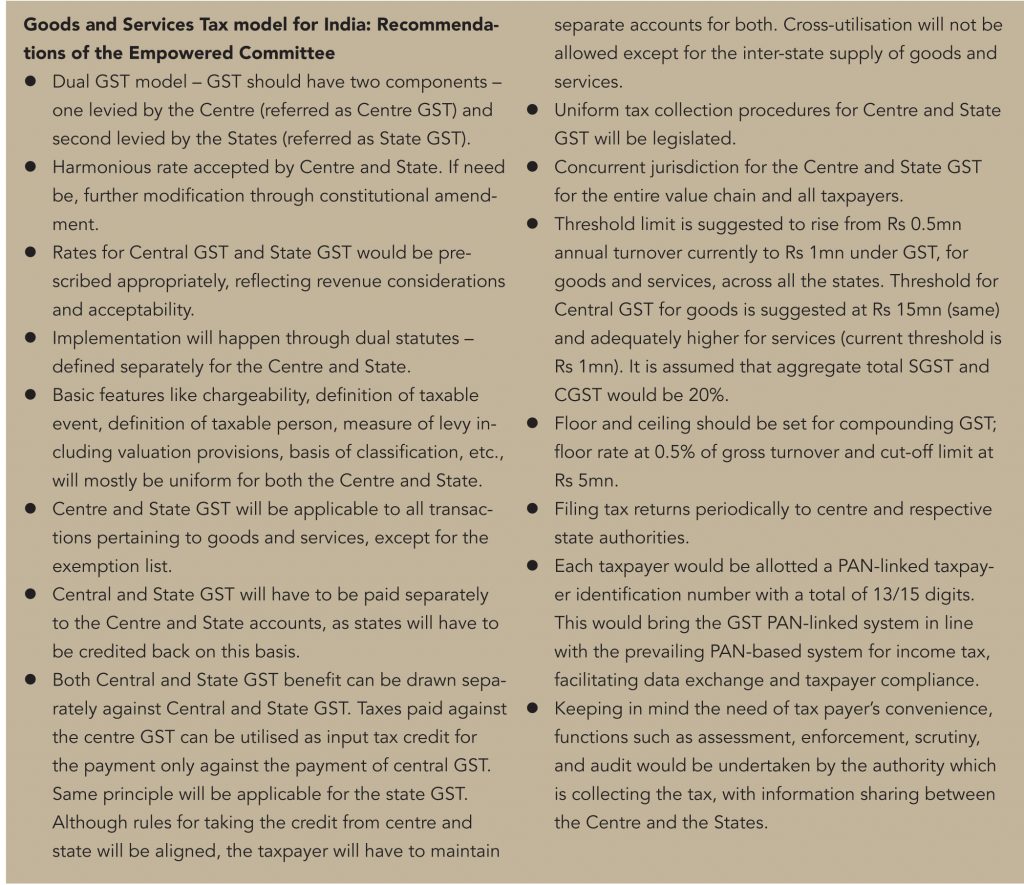

• Subsuming all state and central goods and services tax under GST

• Dual GST model – each transaction will be taxed by centre and state; tax to be referred as Centre GST (CGST) and State GST (SGST)

• Tax rate for CGST and SGST is currently aimed towards revenue neutrality

• Appropriate compensation to states

• Minimalistic exemption list (goods and services) to ensure maximum benefit; free-flow of tax credit in intra and inter-states

• Uniform tax collection and filing procedures for SGST and CGST

• Constitutional amendments to introduce CGST and SGST (possibly two separate laws)

• Seamless IT infrastructure, online tax administration

Key features of GST in India (known so far)

• Tax rate – Undecided as yet

• Coverage – All goods and services, except the basic exemption list. Currently states have reservations on including alcohol, petroleum, and entry tax.

• Threshold – Rs 1mn for SGST on goods & services; Rs 15mn for CGST for goods manufacturers, adequately higher for service providers

Benefits of GST

• Simplistic tax structure – one tax (GST) in place of many taxes

• Transparency for consumer and government

• Higher compliance as credit benefit is available across the supply chain for goods and services (from producer to retailer)

• Higher revenue generation due to wider coverage and greater compliance

• Industry to benefit significantly due to benefit of setting-off of taxes paid across the supply chain and tax simplicity

• Prices for the consumer are likely to fall due to the credit benefit for the industry and services (tax rate will be the decisive factor)

Currently, centre collects taxes from 66% of the resources, and the balance 33% is left for the states. GST can only be implemented with the consensus of states and centre as a constitutional change will be required. Passing the tax law would require two-third votes in both houses of parliament, plus the support of 15 of the 29 states to amend the constitution. Most of the states’ objections to GST revolve around loss of autonomy and perceived loss of revenue from petroleum and alcohol.

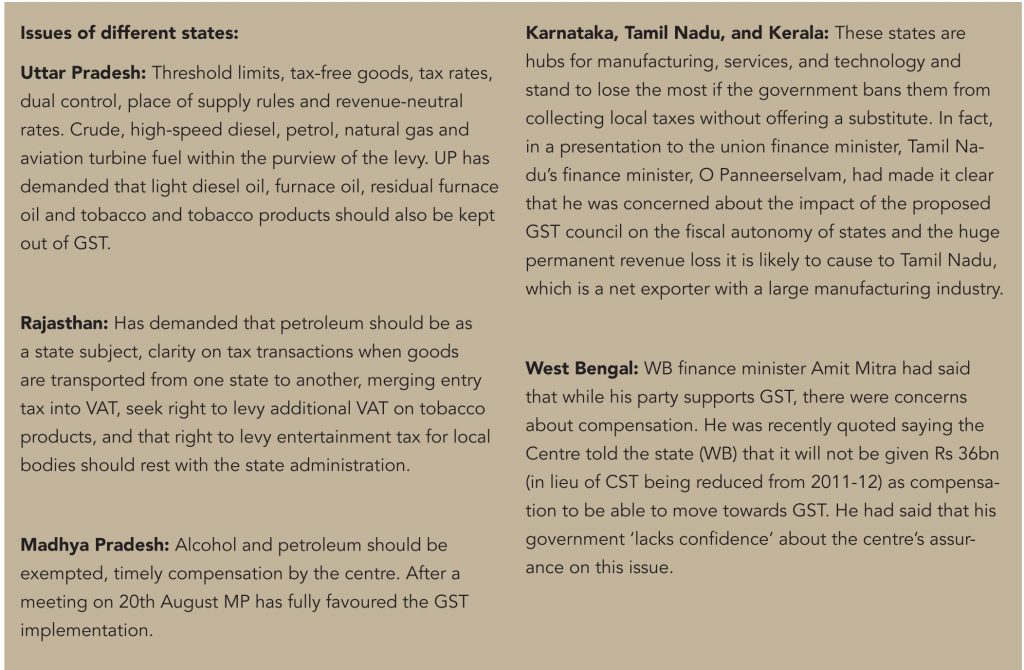

However, from being wary of introducing GST, many states have now agreed to accept GST with a few riders and exemptions. In the UPA government’s regime, BJP states were against GST. However, with the NDA government at the centre and more states also BJP-ruled, the chances of faster GST implementation are higher. So far, the response from BJP-ruled states (like Rajasthan, MP) is not full acceptance but conditional acceptance. SP-ruled UP has mildly loosened its stringent position against GST.

Experts believe that most of the state and centre taxes should be subsumed under GST to ensure simplicity,compliance, revenue generation, and benefit of all tax-paying agents.

Benefits to states

The GST at the state-level is justified because:

• States get the additional power of levying service tax

• System of comprehensive set-off relief, including set-off for cascading burden of CENVAT and service taxes

• Subsuming of several taxes in the GST

• Removal of burden of CST (CST has been reduced to 2% and will be abolished once GST is introduced).

The state’s list of concerns include

• Loss of revenue and fiscal autonomy: Industrial states like Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu receive 77-80% of revenue receipts from their own taxes while it is at 27-28% for states such as Bihar and J&K (rest of the revenue comes from centre allocations). Total losses to all the states are estimated by the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) at Rs 320bn, based on calculations taking 2007-08 as the base year. On the other hand, the task force under the 13th Finance Commission has suggested a provision of Rs 500bn as compensation for 5 years.

• Quantum and timing of compensation from centre: The Empowered Committee has recommended that adequate compensation should be provided to states for the loss that might emerge due to GST implementation for the next five years released as special grants to the states every month on the basis of a neutrally monitored mechanism.

• Producing states at loss: GST is a consumption-based tax and not origin based. Under GST structure, the tax would be collected by the states where the goods or services are actually consumed i.e., where the goods are actually sold and not the state where it is actually originated. Hence, losses could be heavy for producing states. States (Gujarat, MP) that were focused on manufacturing developed huge infrastructure and will suffer. However, the centre believes that there is no evidence yet that exporting states will suffer.

• The rate of GST

• Entry tax, alcohol, and petroleum goods should not be subsumed in GST. States are being convinced and the possibilities of allowing states to levy additional taxes (over and above SGST) in lieu of entry tax, petroleum products, and alcohol, are being considered.

• States demand legal control of central GST up to a limit of Rs 15mn — centre is willing to give only administrative control. States are worried that their small businesses will fall under centre GST. Dual-control is prescribed and accepted above Rs 15mn.

• Control over small traders in the new tax regime.

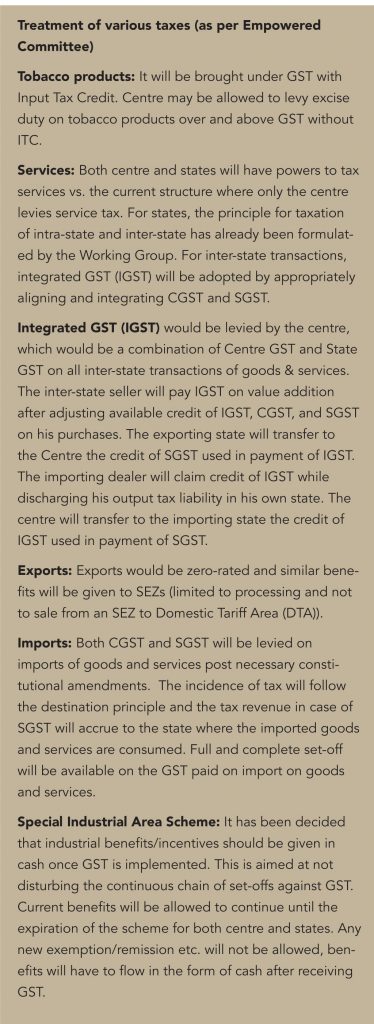

Treatment of alcohol: Close to 20% of the states’ revenue is generated from alcohol; it is the second-largest source of revenue for states after sales tax – and the reason states are wary of letting go of alcohol taxation to GST. Alcohol consumption is barred in Gujarat, Nagaland, Mizoram, and Manipur. For Tamil Nadu, 27% of the revenue came from alcohol in FY13 and for Kerala, it stood at 22%. Alcohol is subject to multiple taxes under the current regime — central excise and state VAT on manufacture and production, sales tax, entry tax, and octroi on sale/movement of goods.

The central government is in favour of including alcohol under GST for the following reasons

• To avoid cascading effect – Tax cascading has adverse impact on volumes, prices, and growth of the sector and resultant lower revenue generation

• If alcohol industry is kept out of GST, impact of CGST and SGST on inputs and services for which no credit is given will have adverse impact on the margins and result in higher prices. Inclusion will facilitate free flow of credits across the value chain. GST will provide credit on inputs and input services

• Exclusion will make tax administration of the industry too complex and costly for the government

• Exclusion will have adverse impact on trade partners (restaurants, transporters, stockists, distributors) and other industries (pharma and perfume manufacturers as alcohol used as raw material)

• Inclusion will lead to better competitiveness in domestic and international markets: No sticking costs

In India, it is being recommended that centre should apportion CGST collections on alcohol with states and SGST should be adjusted to ensure revenue neutrality.

Internationally, alcoholic beverages are taxable at two levels

• VAT / GST (as the case may be) – levied on movable goods and services (with few exceptions)

• Excise duty (non-recoverable) – levied only on specific goods.

• VAT / GST paid on inputs can be off-set in the hands of registered manufacturers

Treatment of petroleum products: Out of the total indirect tax collections of the centre, approximately 23% came from petroleum taxes in FY14. For states it stood approximately at 10-12%.

Current tax treatment of petroleum products

• To central government: through customs duties, cess on crude oil, excise duty and service tax charged on input of services.

• To state government: through sales tax/ VAT and central sales tax

• In addition to central and state taxes, octroi and entry tax are revenues that accrue to local bodies.

Problems with the current regime and exclusion from GST will result in:

• Cascading of taxes, which will have price impact on other sectors; this is because petroleum is a key input for various industries (railway, water, airways, fertiliser)

• Making exports of petroleum products uncompetitive

• Impact revenue collection

A study done by NIPFP has shown that GST implementation will either lead to prices of petroleum goods remaining unchanged or declining (except for tax exempted sectors). These results suggest that there is little reason for leaving out petroleum products from GST.

Entry tax is a tax imposed on the movement of goods from one state to another — it is levied by the recipient state to protect its tax base. It’s a tiny tax but amounts to huge complexities in compliance and also results in discrimination of goods. This tax was earlier levied by local civic bodies on mere entry of goods into its local area and collected in cash at check-posts by the road side. There was no mechanism for collecting the tax on trains or air cargo. Given the inefficiencies of collecting it at the entry point, the tax is now levied on the basis of information in the accounts of the dealers.

The entry tax is an impediment to free flow of trade and is a source of competitive distortions and inefficiencies in the supply chain. Gujarat has already eliminated entry tax by increasing its VAT. Entry tax has been held unconstitutional by various high courts across the country.

To address the concerns of states on revenue loss on account of entry tax, it is being suggested that states may be allowed to levy additional 0.5-1% rate over and above the state GST. This amount could then be transferred to their local municipalities.

States have agreed on

• Threshold levels for GST implementation at Rs 1mn (Rs 0.5mn for special-category states).

• Harmonise the exemption lists of states and the centre, which has 96 and 243 items, respectively.

• MP and Gujarat have agreed to favour GST while congress-ruled Haryana has hardened its negative stance (pertaining to purchase tax as the state gets Rs 40-50bn from agriculture). Tamil Nadu stayed with its stance of fiscal autonomy of states.

The empowered committee has decided to adopt a two-structure approach in implementing GST — lower rate for necessary items and a standard rate for goods in general. Special rate will be set for precious metals and a list of exempted items. Decision on current exemption list under VAT (to remain exempted for an initial few years) is yet to be taken. Similar decisions are to be taken for the exemption list for the Centre GST. For services, a single rate is advised for both Centre GST and State GST.

As of now, the government has not shared its thoughts on the tax rate of GST; experts’ opinions vary from a rate of 16% to as high as 24%. Experts have stated that a single rate for goods and services will be preferred. GST rate for state and centre is not crucial for the industries and consumers. A few government officials have stated that the two rates being considered are 8-10% for the lower slab and 16-18% for the higher slab. In addition, states can levy a 1% additional tax on precious metals and a list of exempted items.

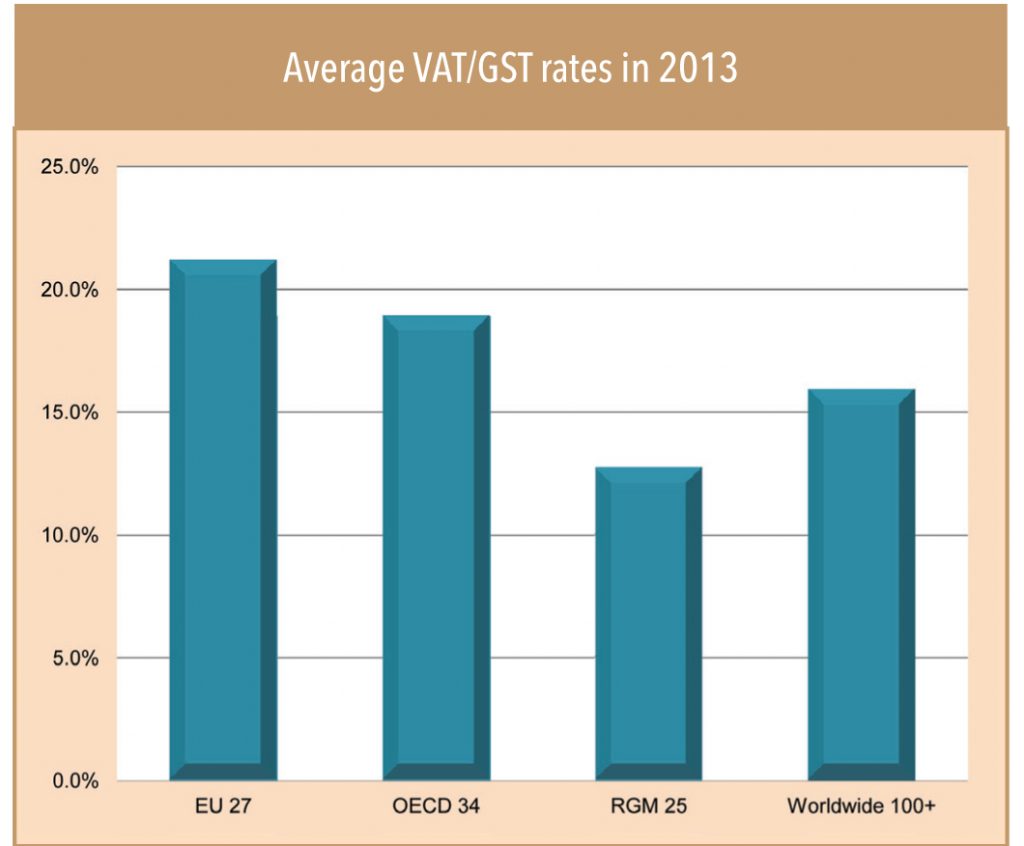

Globally, GST rates vary from 5-27%; Singapore, Canada – 5%, OECD average – 19%, and Hungary– 27%. World average GST rate stands at 15.9%, lower than 21.2% for 27 EU countries and 19% for 34 OECD countries. The GST rate set by the rapidly growing economies (suitable category for India) is lower at 12.7%. Of the 25 RGMs, 11 apply rates of 15% or more (Argentina, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Ghana, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Turkey and Ukraine), and although no RGM rate reaches the heights of 27% (the world’s highest VAT rate, which is charged in Hungary) four RGMs do charge rates at or above 20%.

The government hopes to table the constitution amendment bill in the winter session of parliament after it agreed to address some of the concerns including the non-payment of central sales tax compensation (CST) and issues surrounding the GST’s design. Since the government will need a 2/3rd majority, and considering that getting to a GST consensus is expected to take longer, GST introduction is unlikely to happen in April 2015 as suggested in the budget. A few tax experts that we spoke with are of the view that considering the current pace of negotiations with the states and requirement of constitutional amendment, GST implementation is possible in April 2016. Others feared that if it is introduced in April 2015, industries are not prepared to implement it.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access