Nobody can survive selling only value- added products. The dairy industry supply chain rides on milk and its procurement,” says Mr RS Sodhi of GCMMF. Milk has two constituents – fat and SNF (solid non-fat). Fat can be used for making butter, ghee, and other value-added products, but after extracting the fat, the SNF has to be sold. If milk is sold separately while a company only focuses on the supply-chain for value-added products, then the supply-chain economics do not work out in a fiercely competitive market.

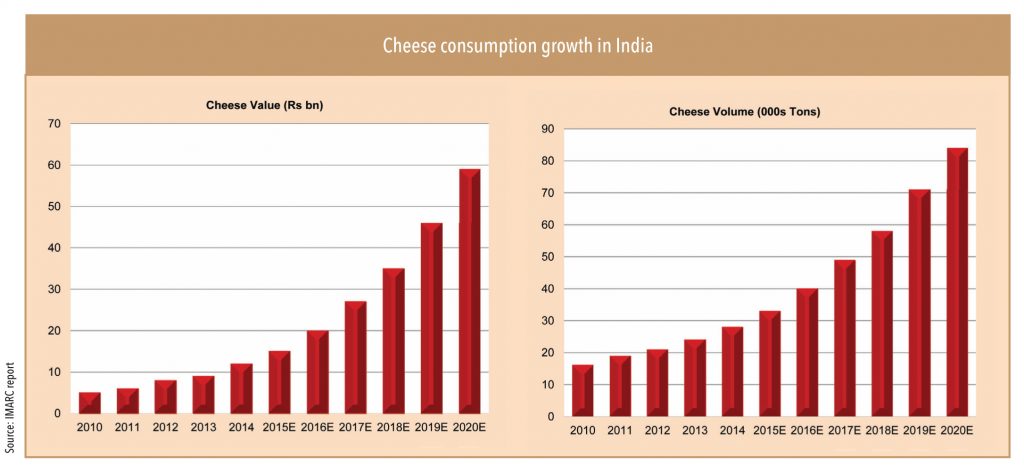

While supply-chain economics are challenging, cheese presents an interesting proposition. The by-product for cheese is whey, but it is produced in limited quantities. The market for cheese is large in developed economies. Some of the biggest companies of the world, such as Kraft, built their businesses on producing high-quality cheese.

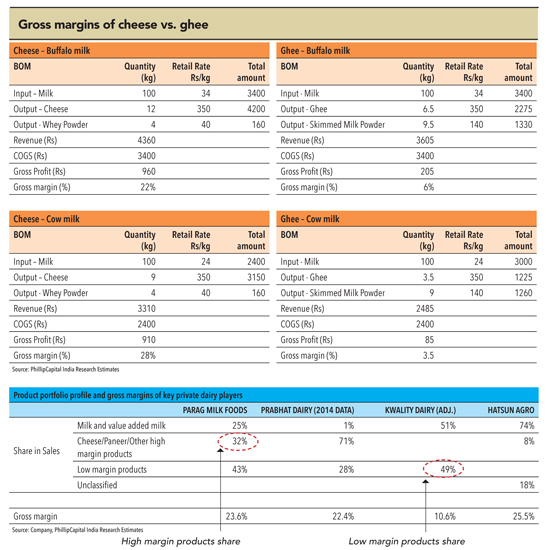

Cheese is among the more profitable value-added milk products with gross margins higher than 25% vs. ghee with 5-10% margins

The value addition in cheese can be significant, as aging is a critical component in manufacturing of cheese. The level of premiumisation that cheese offers is absent in any other dairy product. While premiumisation opportunities are significant, and there is a global precedence of successful business models built on cheese, the market for cheese in India is rather limited currently. It is seeing magnificent growth rates, but hasn’t become a standard grocery item such as ghee or butter.

Cheese-making commands higher gross margins than ghee, because it is a complex process. Cheese requires aging of three months or more, depending on the grade. This aging is done in cold storage, which significantly pushes up the working capital and fixed capital requirements. The return on investment on cheese depends on the retail and wholesale (institutional) mix as well as the ability to utilise capacity. Moreover, the wide range of cheese – from basic mozzarella to exotic varieties – offers significant brand-building avenues. A recent example is Parag Dairy’s introduction of a premium cheese spread under the brand name Almette. Building brands in dairy businesses has been challenging, and only products that command pricing power can be considered brands. However, established brands can command a premium to regional and local products and generate higher gross margins.

Apart from cheese, the range of value-added products is quite large in India. These products are less impacted by changing global commodity prices. For example, in the current scenario of a sharp correction in global skimmed milk powder (SMP) prices, domestic ghee prices have been relatively steady. The decline in global SMP prices has led to a complete stalling of SMP exports from India. Private players involved in SMP exports have significantly reduced their procurement of milk, and cooperatives have had to step up procurement. For the dairy industry, in the current scenario, ghee and buffalo milk (with higher fat content) have emerged as saviours. Buffalo milk prices are expected to bounce back as the lean summer season ensues.

While cheese could technically be a successful business by itself, the market for cheese in India (so far) is limited

“It is the buffalo that is probably going to save the dairy farmer,” believes Mr RS Sodhi, “as cow’s milk and SMP continue to remain under pressure”.

Other high-margin value-added products like UHT (ultra-high-temperature) milk and flavoured milk provide gross margins of around 50% and 70% respectively. However, the capital investment required for such products is high due to the complex nature of operations and asset turnover tends to be in low to mid-single digits.

Needless to say, a wide portfolio of value-added products is critical to the dairy business model, but so is liquid milk, as it forms the key cog of the supply-chain and branding.

The supply-chain and branding enigma of the dairy industry

“If I have to pick the most critical success factor for the dairy business, it has to be the supply chain. We calculate supply chain costs in paise and we keep our costs very low, which helps us to win markets,” says Mr Sodhi. In dairy, everything depends on efficient supply chain. Product quality to profitability– all depend on its efficiency. Most dairy products are highly perishable and require cold chains. A cost-efficient supply chain is a pre-requisite for most industries, but in dairy, these efficiencies go much further. The biggest hurdle in the dairy business is to build brands, and brands need to be scalable. The answer lies in managing supply-chain dynamics.

For a dairy producer, an efficient supply chain is far more important than for other industries, partly because of the perishable nature of the commodity

Consumer-facing businesses are all about brands. These have pricing power and are able to withstand the vagaries of economic cycles. The dairy industry is very large, but since it is dominated by co-operatives, the challenge for companies has been to build brands, considering lower gross margins across products. This, however, is not the only difficult aspect; the bigger challenge in the dairy industry has been to build brands by distributing liquid milk, which while providing unparalleled customer reach, is a rather dull business with EBIDTA margins of around 5%. Nevertheless, it has multiple advantages, which most private companies fail to commit to over the long term. The biggest advantages are:

• Supply of quality milk provides a direct connect with end consumers at lower costs and results in branding

• Provides economies of scale; plus, it is a cash business with lower working capital requirements

• Brings down the supply-chain costs on which other products can ride

All these three big advantages are a must for building a scalable consumer business, but the challenge is the ‘right to win’ in building such a consumer-facing franchise. Most FMCG companies ask themselves three ‘right to win’ questions:

• Do we have any special skill or advantages in sourcing of products?

• Do we have the brand/branding capabilities?

• Do we have the distribution infrastructure?

For most companies, getting a positive answer for any two of these equals a green signal to develop those products.

Dairy is an exciting and lucrative segment (when done right) and most FMCG companies keep mulling over cost-effective ways of tapping into it

However, in dairy, companies need to get all three questions right. This seldom happens, but companies that do, go on to build scalable businesses. Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation, owner of the iconic Amul brand, met all the criteria and has exceeded expectations. Hatsun Agro is another company that built a strong brand and capabilities, while Parag Milk Foods is the other player that managed to build a robust business model. These models have met with success because of their long-term vision.

Extending brands to dairy: Strategy still in the lab

Building dairy brands are long-gestation projects. Companies have to slog in the retail channels with low-margin products, consistently improve efficiencies, and build higher-margin value-added products. All this is a fairly long process. Brand extensions are a seemingly easier route to brand building in this segment, but the efficacy of this method is not fully proven. Some of the leading FMCG companies have forayed into the dairy business through brand extensions. Britannia and Nestle are developing their dairy franchise around the flagship brand. Nestle has met with the most success, primarily because of its first-mover advantage in infant nutrition and dairy creamer. The infant nutrition category is also impacted by regulatory hurdles (not allowed to advertise), but Nestle was able to take advantage of market conditions when regulatory hurdles were much lower. In the dairy-creamer category too, the company enjoyed first-mover advantage and it was able to build a very successful brand. Nestle’s success in these two products has not been repeated by any other player; in fact, even Nestle itself could not repeat its success in other dairy categories, notwithstanding global expertise and experience.

Britannia and ITC both have ambitious plans for the category, but do not seem to have a coherent strategy in place yet. However, since these companies have strong brands, experience in sourcing, and supply-chain management capabilities, the ‘right to win’ is seemingly inherent. Strategically, most FMCG companies shy away from low-margin businesses such as liquid milk, as they find capital-efficiency lacking; their preference is mostly towards high-margin categories. The success of this strategy is yet to be proven or probably the market is still to reach that inflection point to make a significant impact.

In this context, the dairy market has surely not reached an inflection point for growth to take off, but more importantly, products like cheese, dahi (curd), or tetra-pack milk by leading FMCG players are yet to capture the people’s imagination. In all probability, the success for this kind of a strategy would lie in a company’s ability to introduce new innovative products that find wide acceptance and still have high margins. For now, the big boys of FMCG are in a ‘wait-watch-development’mode for distruptive innovations.

Crude is not the only product flooding the world

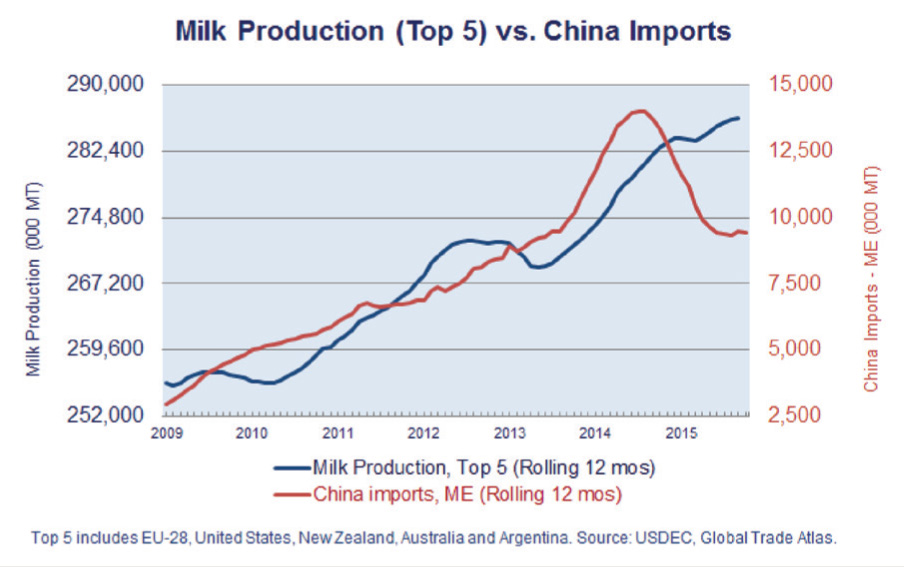

While the commodities and therefore financial markets suffer from the impact of an oil glut, for the farmer community the oversupply of another commodity (less talked about but more impactful) has been wreaking havoc globally since last two years – milk!

Global milk prices have been falling since the past two years, led by increasing supply from all major producers amidst falling demand from China and Russia. While the milk production of top-5 exporters increased consistently, milk import demand from China fell ~30% in the last two years due to slowing down of demand growth and strong growth in domestic production.

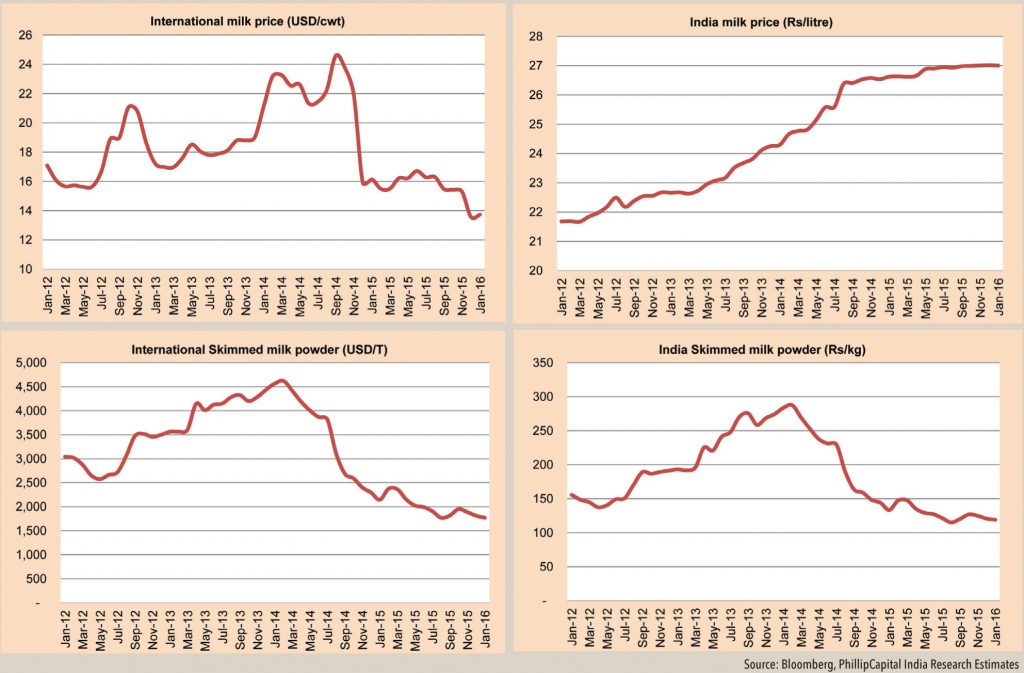

Falling milk prices led to a drop in prices of most dairy products globally. In the last two years, milk prices dropped 35% and skimmed milk powder prices dropped 60% .

Even though India consumes most of its domestic production and is therefore not a big exporter, falling prices have impacted Indian markets too, albeit to different extents on different products. While prices of milk have increased by 11% in last two years due to the dominance of co-operatives, prices of skimmed milk powder have fallen in line with global prices (by 60%).

Marc Beck (VP Strategy, US Dairy Export Council) says “It may be 2017 before we return to a scenario

where global supply and demand for milk are more closely aligned.” This is because the key factors necessary to deliver better market balance — production contraction, inventory reduction, and China buying — have yet to materialise.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access