Objective and need for the project

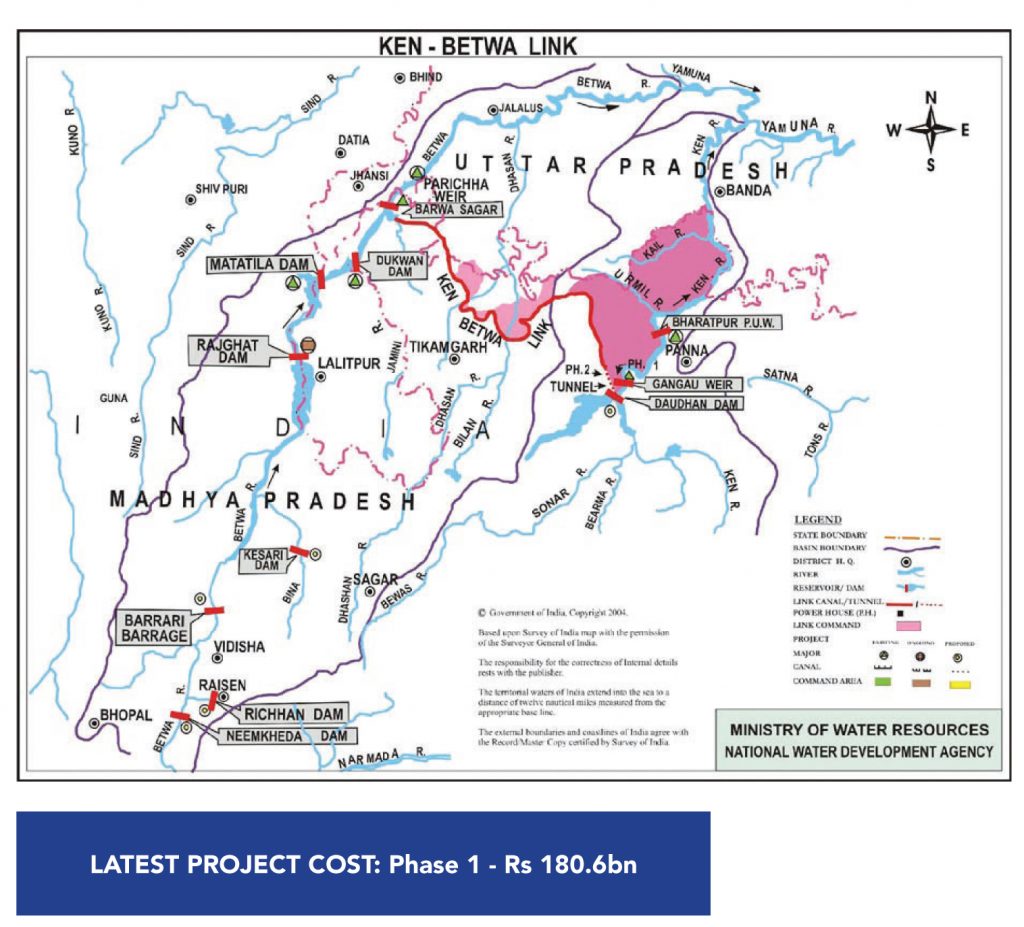

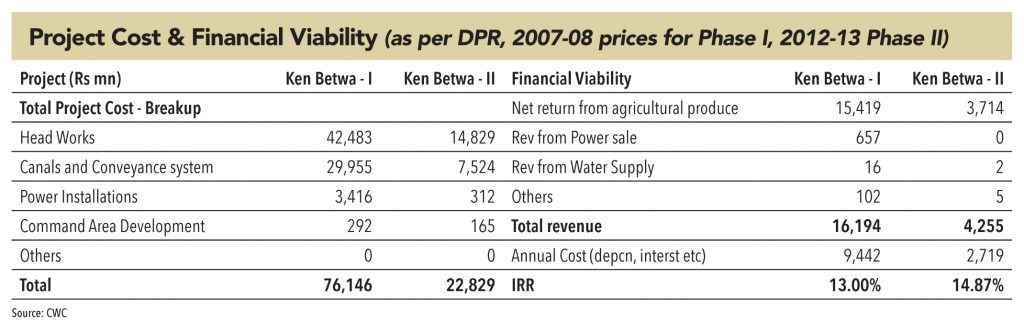

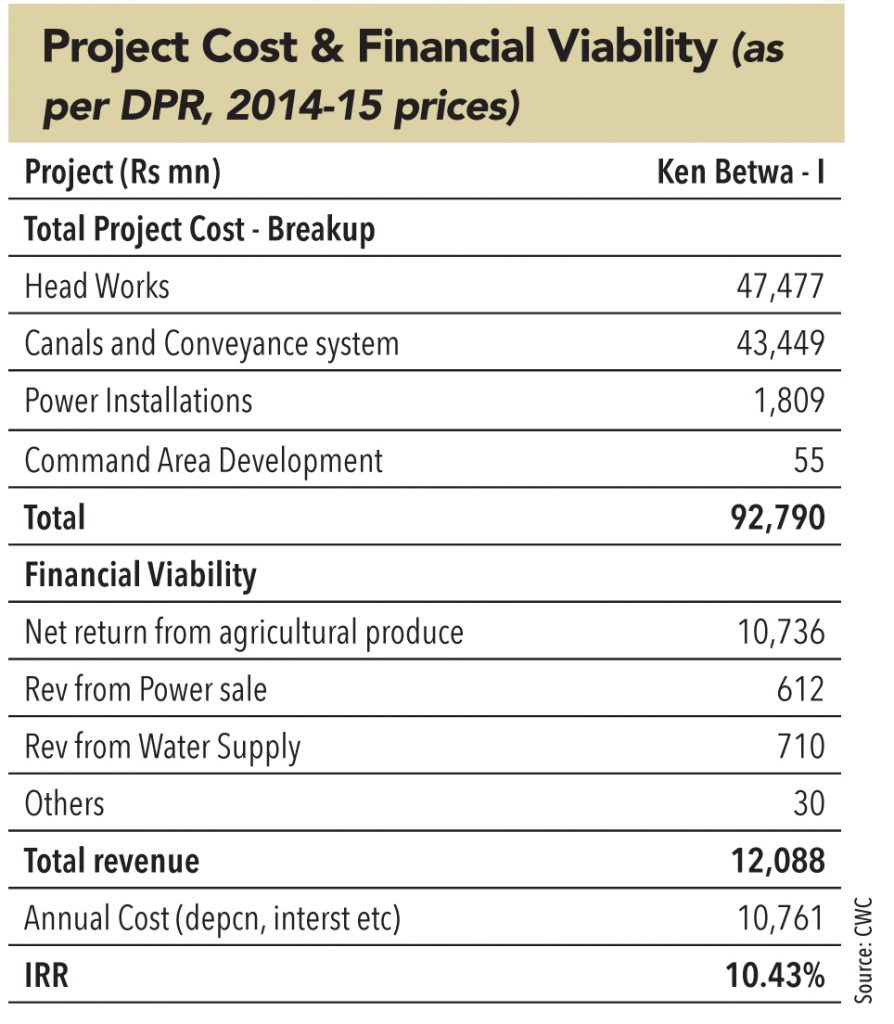

The main objective of the Ken-Betwa link project is to make water available to deficit areas of the upper-Betwa basin through substitution from the surplus waters of the Ken basin. As per an NWDA study, the Ken river basin (up to the Greater Gangau dam site) was found to be water surplus. Accordingly, a toposheet study and preliminary feasibility study of the Ken-Betwa link were carried out.

Development timeline

The feasibility report for Ken-Betwa Link was prepared by the NWDA in 1995 after which efforts were made by NWDA, CWC, and the Ministry of Water Resources to arrive at a consensus between the two beneficiary states – Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Madhya Pradesh (MP). Finally, a consensus did come through and the centre and concerned parties (MP, UP, and the Union Government) signed a tripartite Memorandum of Understanding on 25th August 2005 for preparing a Detailed Project Report (DPR) for the link.

The Ministry of Water Resources entrusted the DPR work to NWDA in January 2006. Three years later, during a secretary-level meeting (February 2009) it was decided that the DPR would be prepared in two phases – in phase-1, Daudhan Dam and its appurtenant works, two tunnels, two power houses, and a link canal would be included; phase-2 would comprise projects proposed by the MP government in the Betwa Basin. The DPR for phase-1 was completed by NWDA in April 2010 and circulated to concerned state governments.

Constitution of the project

Two dams (Daudhan and Makodia) and two barrages (Kesari and Barari) are proposed under this link. Due to topographical constraints, sufficient command would only be possible after proposing a lift up to 425m for Barari and 410m for Kesari barrage. Therefore, MDDL (minimum drawdown level) of both barrages are tentatively fixed as 401m. Two powerhouses are proposed in Daudhan Dam Complex. Phase-1 will have an installed capacity of 60 MW (2 x 30 MW) whereas the second phase will have 18 MW (3 x 6 MW).

Out of the total divertible quantity of 1074 MCM, 366 MCM of water (277 MCM for MP and 89 MCM for UP) will be used for en-route irrigation of 60,000 ha. in the districts of Tikamgarh and Chhatarpur of MP and Mahoba and Jhansi of UP, with 100% intensity of irrigation. After taking into account the requirement of en-route water-supply needs (49 MCM) and transmission loss of 68 MCM, the balance 591 MCM of water will be delivered in to the Betwa river, upstream of the Parichha weir.

Out of this 591 MCM, about 273 MCM of water, by way of substitution, will be used through the proposed projects – Makodia, Kesari, and Barari barrages – for irrigation of 62,000 ha. in the Upper Betwa sub-basin. The area that will benefit through these projects lies in Raisen and Vidisha districts of MP. The government of MP is expected to plan new projects for utilisation of remaining water.

It is proposed to provide 398 MCM of water to MP for irrigation in the Ken command through the Bariarpur pick-up weir across the Ken river, located downstream of Daudhan dam, which will irrigate an area of 68,300 ha. Similarly, 1,007 MCM of water is proposed for irrigation of 0.17 mn ha. in MP through the left bank canal (taking off from the tail-end of lower level tunnel), upstream of Daudhan dam.

Because of this project, a large area of Bundelkhand (330,000 ha. of MP and 14,000 ha. of UP) is expected to come under assured irrigation – which will increase agricultural production and productivity in the area.

Ken Betwa Phase 2:

The NWDA started preparing the phase-2 DPR in January 2011 and completed it in a record time of three years in January 2014. The project is mainly an irrigation scheme, with a small component of drinking-water supply. It consists of a dam (Lower Orr), four barrages (Neemkheda, Barari, Kotha, and Kesari) and a network of canal systems. The project will provide irrigation to an area of 98,847 ha. in Shvpuri, Raisen, Vidisha, Sagar, and Ashoknagar districts of MP, and drinking water supply to 0.16 mn population of Shivpuri (MP).

Objective and need for the project

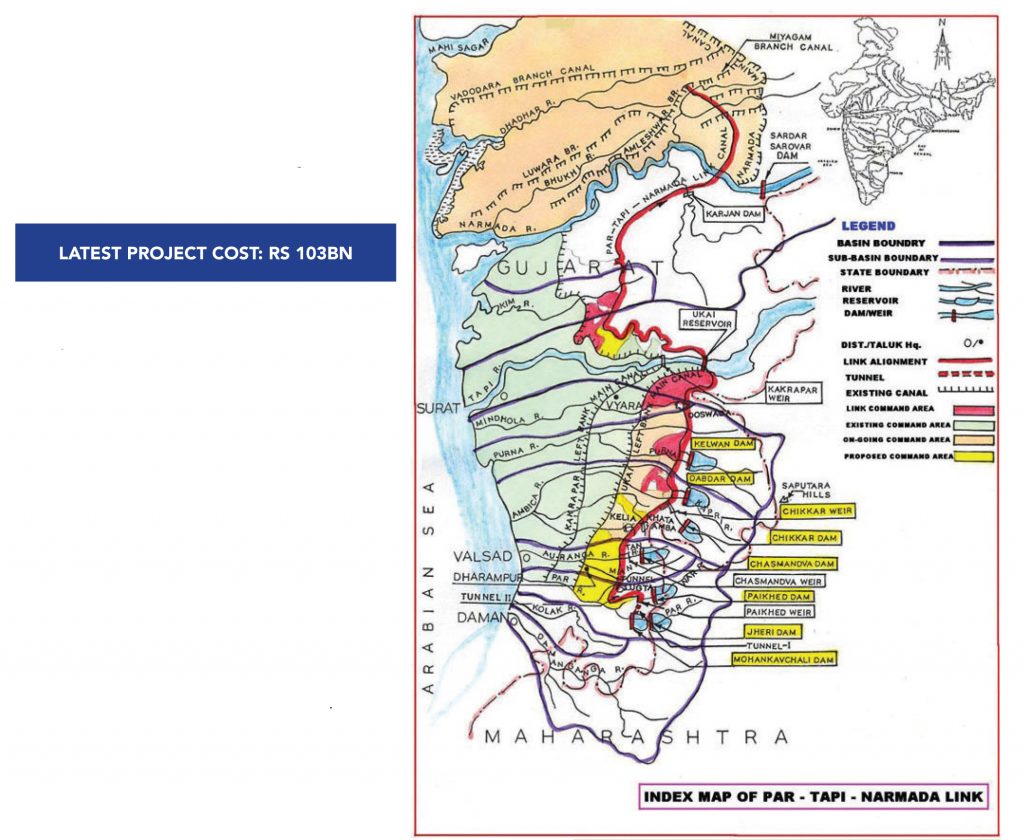

The main objective of the Par-Tapi-Narmada Link Project is to transfer water from the water-surplus regions of the Western Ghats to the water-deficit regions of Saurashtra and Kutch. The project will also cater to the command areas of five projects – Khuntali, Ugta, Sidhumber, Khata Amba, Zankhari – proposed by the Government of Gujarat. This link will serve:

There is a wide variation in distribution of water resources in different regions of Gujarat due to variation in rainfall, which is very scanty in Saurashtra and Kutch and the area is frequently affected by droughts. Par, Auranga, Ambica, Purna, and Mindhola are important west-flowing rivers in the Western Ghat region (north of Mumbai, and south of Tapi) in southern Gujarat. All these rivers originate in Maharashtra, and after flowing through the state and through Gujarat, they outfall into the Arabian sea. Only about 14% of the catchment area of these rivers lies in Maharashtra and the remaining 86% lies in Gujarat.

Out of total 38,100 MCM of estimated utilisable surface water resources in Gujarat, the ones in south and central Gujarat are 31,750 MCM (83%). However, there is large variation in per-capita water availability in different regions of the state. The per-capita water availability in south and central Gujarat is about 1,100 m3 (2011 census) and it is about 600 m3 in Saurashtra and Kutch. With the anticipated growth of population in the state by 2050, the availability should reduce further. The rivers in Saurashtra and Kutch are mostly dry through the year, whereas sizeable quantum of flows of Par, Auranga, Ambica, and Purna rivers situated in south Gujarat are going to sea unutilised every year.

In the light of the above scenario, the Par-Tapi-Narmada Link Project is envisaged to transfer the surplus flows from west-flowing Par, Auranga, Ambica and Purna rivers between Par and Tapi to water deficit drought-prone regions lying on both sides of the link canal, towards the north, including tribal areas, and up to drought-prone Saurastra and Kutch regions.

Development timeline

The feasibility report of the Par–Tapi–Narmada link project was prepared by NWDA in October 2005, and circulated to the concerned state governments (Gujarat and Maharashtra) and members of Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) of the NWDA. Since then, continuous efforts were made by NWDA, CWC, and Ministry of Water Resources to arrive at a consensus between two beneficiary states, which eventually resulted in an agreement to prepare a Detailed Project Report (DPR).

A tripartite MoU was signed by Gujarat, Maharashtra, and the Union Government on 3rd May 2010 for preparing a DPR, which the NWDA completed in August 2015 and sent to the water resources departments of both state governments. The issues of water-sharing and power-sharing between Gujarat and Maharashtra were discussed at multiple levels over the next year. The Union Minister for Water Resources also held meetings with the Maharashtra chief minister at Mumbai on 3rd May 2016 (discussed Damanganga-Pinjal and Par-Tapi-Narmada Link Projects among other issues).

Constitution of the project

The link project includes six reservoirs proposed in north Maharashtra and south Gujarat. The water from the proposed reservoirs would be taken through a 406km-long canal, including the 33km length of the feeder canals, to take over a part of the command of the SardarSarovar Project, while irrigating small en-route areas. The project comprises construction of six dams:

i) Jheri Dam across river Par in Peint taluka of Nasik district in Maharashtra

ii) Paikhed Dam across river Nar – a tributary of river Par

iii) Chasmandva Dam across river Tan – tributary of river Auranga– all in Dharampur taluka of Valsad district in Gujarat

iv) Chikkar Dam across river Ambica

v) Dabdar Dam across river Khapri – a tributary of river Ambica

vi) Kelwan Dam across river Purna – all in Ahwa taluka of Dang district in Gujarat.

Construction of two diversion barrages – one each in the downstream of Paikhed and Chasmandva dams, six powerhouses and a 406km-long link-canal (including feeder pipeline and tunnels along the link canal) connecting all six dams with the existing Miyagam branch canal (of the Narmada canal system from the Sardar Sarovar Project) are envisaged.

The surplus water proposed for diversion through Par-Tapi-Narmada link project will provide irrigation to a total area of 232,175 ha., of which 61,190 ha. is en-route the link canal:

The command area of five projects proposed by the government of Gujarat on the left side of the canal is about 45,561 ha. to be irrigated by gravity through a link canal. The tribal area on the right side of the canal is 36,200 ha., which will be irrigated by lift. About 12,514 ha. of tribal area will also be irrigated directly by lift from the proposed six reservoirs. Narmada water, so saved, will be used to provide irrigation facilities in the tribal area on the right side of Narmada main canal to the extent of 23,750 ha. in the Chhota Udepur district and 10,592 ha. in the Panchmahal district (through lift on substitution basis), and 42,368 ha. in Saurashtra, Gujarat. A provision of about 76 MCM of water is allocated to meet drinking-water supply to 2.76mn population in the above areas. Also, a provision of 50 MCM is made for filling of 2,226 panchayat and village tanks/check dams in the benefitted areas. The project will also generate about 102 MU of hydropower from the powerhouses proposed at various dams and the canal fall, besides providing drinking water to the villages in the region.

The total utilisation through Par-Tapi-Narmada link from six dams will be 1,330 MCM. However, at a later stage, when the public hindrance is resolved and the required field survey and investigations are carried out, the proposed Mohankavchali dam will also be dovetailed with the Par–Tapi–Narmada link project.

Objective and need for the project

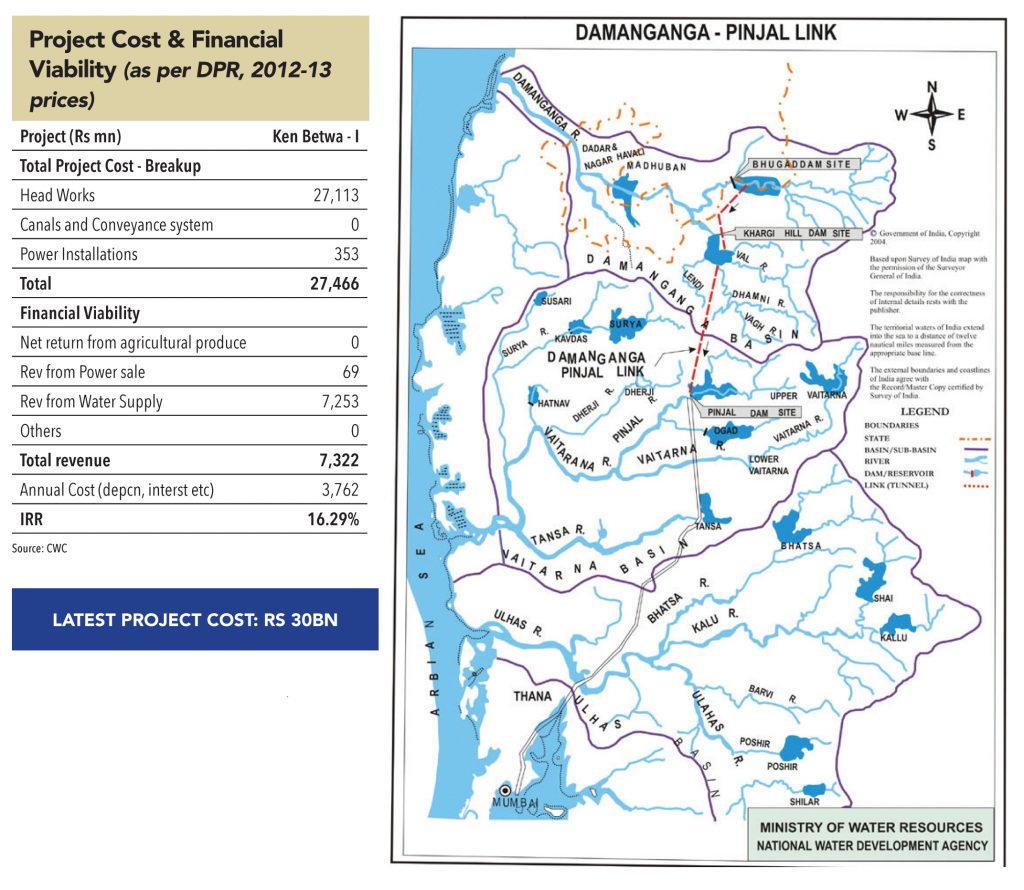

The objective of the Damanganga project is to divert surplus water of the Damanganga river at Bhugad and Khargihill reservoir to the Pinjal reservoir in Vaitarna basin (proposed by the government of Maharashtra) for Mumbai city, in order to augment the city’s domestic water supply.

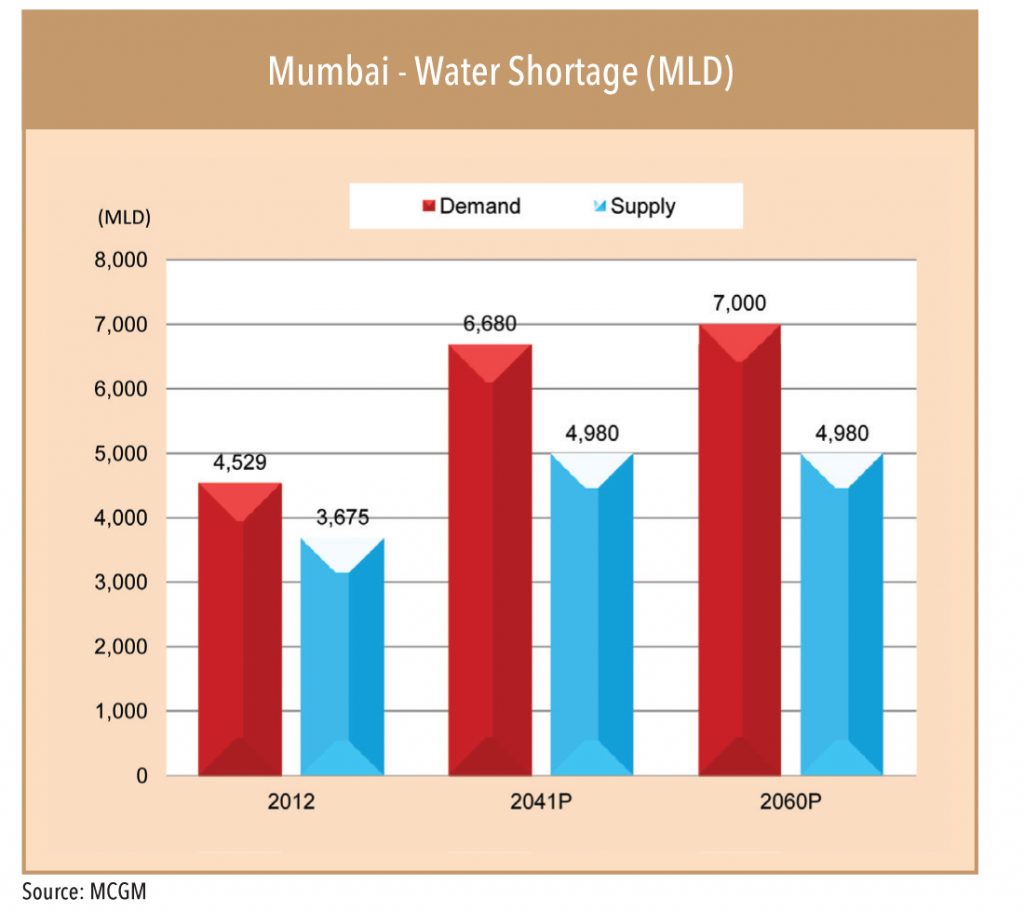

With the present pace of development of Greater Mumbai, it is anticipated that there would be acute shortage of domestic water in the year 2050. As per the assessment of the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM), the current (2012) shortage of water supply of 854 MLD (Million litres per day) will increase to 1700 MLD in 2041 and 2020 MLD by 2060.

Development timeline

The feasibility report of the Damanganga-Pinjal Link Project was prepared by the NWDA in November 2004 and circulated to all concerned State Governments and members of Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) of NWDA. After consensus was arrived amongst the Central Government and concerned States of Gujarat and Maharashtra, a tripartite Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed by the states and the Union Government on 3rd May, 2010 at New Delhi for preparation of the DPR.

Subsequently, the NWDA took-up various surveys, studies and investigation works with the help of expert agencies to complete and submit the DPR in March, 2014. Thereafter, various obstacles related to project execution have been cleared.

The Union Minister for Water Resources also held meeting with the Maharashtra CM at Mumbai on 3rd May, 2016 where in Damanganga-Pinjal and Par-Tapi-Narmada Link Projects were discussed among other issues

The project requires ‘Tehcno Economic Clearance’ from the CWC, and the ‘resettlement and rehabilitation of population’ clearance from the Ministry of Tribal Welfare. The Ministry of Environment & Forest (MOEF) indicated in a letter in 2008 that the project does not come under the provision of EIA Notifications, 2006, as it is a drinking-water-supply project and hence such environmental clearance is not required.

Constitution of the project

For this project, the following have been proposed:

In addition, two tunnels are proposed:

The surplus water available at the proposed Pinjal reservoir, along with the water to be transferred from proposed Bhugad and Khargihill reservoirs of the Damanganga basin, is to be taken up to Mumbai city through a suitable conveyance system as per the planning of the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCBM) and Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA).

The powerhouses at the toe of both Bhugad and Khargihill dams are also likely to generate hydropower by using water proposed to be released to meet the water requirements downstream of the respective dam sites.

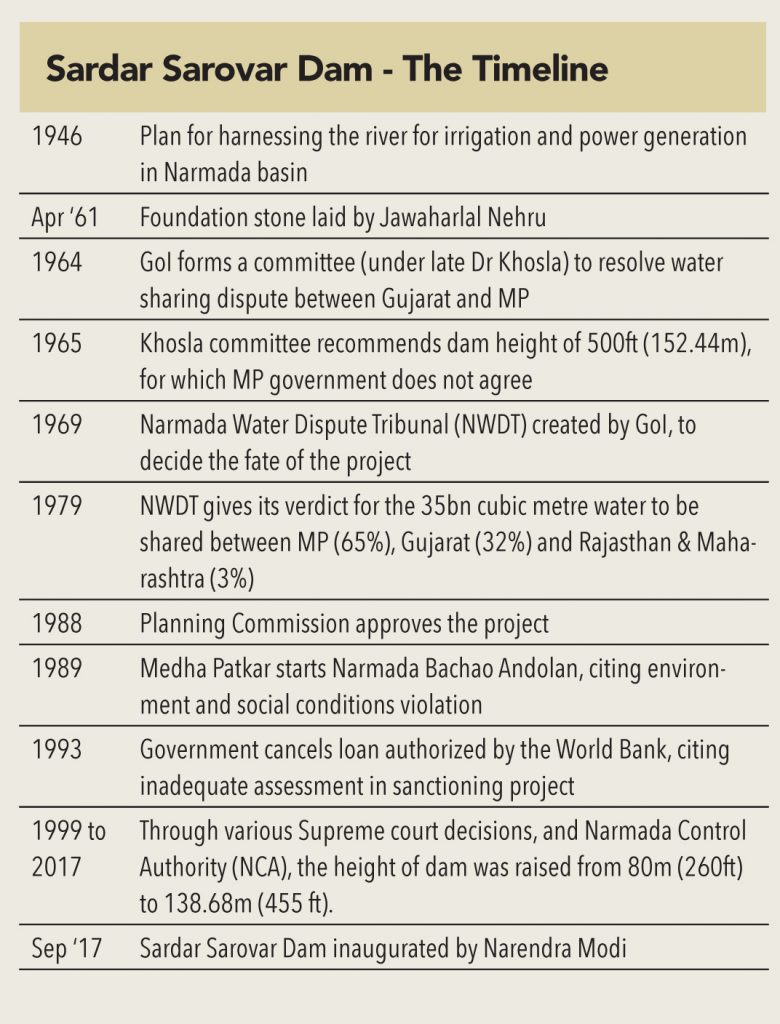

While the NRLP might offer tremendous value proposition, it will be puerile to underestimate its challenges. To understand the execution challenges in the constructing of over 100 dams and 15,000km of canals, one doesn’t need to go far – the challenges faced and the execution timeline of the Sardar Sarovar dam in Gujarat is a good example of how difficult things can get. The project, which has been the subject of much controversy for decades, is said to be one of the largest dams in the world. At a length of 1.2km and a height of 138m, the benefits of this dam will be shared by MP, Maharashtra, and Gujarat.

The Sardar Sarovar project was the vision of India’s first deputy prime minister – Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. The foundation stone of the project was laid by Jawaharlal Nehru (India’s first prime minister) on April 5, 1961 – after a detailed study was carried out on the usage of the Narmada river water flowing through the states of MP and Gujarat, and into the Arabian Sea. The DPR prepared led to many disputes over the distribution of water among three states – Gujarat, Maharashtra and MP. Consequently, a Narmada Water Dispute Tribunal (NWDT) was created in 1969, to resolve the water sharing disputes.

After studying multiple reports and negotiations, the NWDT in 1979 proposed thatout of the 35BCM of water available from the dam, MP would receive 65%, Gujarat 32%, and Rajasthan and Maharashtra the remaining 3%. The Planning Commission approved the project in 1988.

As the project was being planned, it caught the attention of social activists who were not happy with the environmental and social damages caused by the dam. Leading the protests was Medha Patkar, who visited the site of the dam in 1985, and started a movement against the project called the Narmada Bachao Andolan that went on to acquire international attention.

At that time, the project was funded by World Bank, which had granted a loan of US$ 300mn. However, the constant agitations forced the World Bank to set up a committee to review the project. It concluded that the assessments made for the project by the Indian government were inadequate, and eventually the loan was cancelled on March 31, 1993.

However, after several years of deliberation the Supreme Court allowed the construction of the dam to proceed, provided it met with certain conditions (primarily related to rehabilitation of displaced people) for every 5m increase in the height of the dam.

Eventually, 56 years after its foundation stone was laid, the dam was inaugurated by the current PM Narendra Modi (on September 17, 2017). The dam has a height of 139 metres and usable storage of 7.7 (MAF) of water. The project will irrigate more than 18,000 sq. km (6,900 sq. miles), most of it in drought-prone areas of Kutch and Saurashtra, and generate 1,450MW of hydropower.

Sardar Sarovar dam was constructed for Rs 600bn and led to displacement of 70,000 people. The NRLP is expected to cost Rs 11trn, and will lead to displacement of much higher number of people. If the SSD took 56 years after its foundation stone was laid – one can imagine the timeline for the execution of the entire NRLP. However, the experience of having dealt with protests and rehabilitation issues in SSD, should hopefully help pre-empt issues and prevent too many delays.

SARDAR SAORVAR DAM

Benefits of the Sardar Sarovar Dam

The project has the potential to feed as many as 20 million people, provide domestic and industrial water for about 30 million, employ about 1 million, and provide valuable peak electric power in an area with high unmet power demand (farm pumps often get only a few hours of power per day). It will also provide flood protection to riverine reaches measuring 30,000 ha. covering 210 villages and Bharuch city and a population of 0.4mn in Gujarat. In addition, recent research shows substantial economic multiplier effects (investment and employment triggered by development) from irrigation development. Set against the future of about 70,000 project affected people, even without the multiplier effect, the ratio of beneficiaries to affected persons is well over 100:1

The benefits of the dam as listed in the Judgement of the Supreme Court of India in 2000:

The argument in favour of the Sardar Sarovar Project is that the benefits are so large that they substantially outweigh the costs of the immediate human and environmental disruption. Without the dam, the long term costs for people would be much greater and lack of an income source for future generations would put increasing pressure on the environment. If the water of the Narmada river continues to flow to the sea unused, there appears to be no alternative to escalating human deprivation, particularly in the dry areas of Gujarat.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access