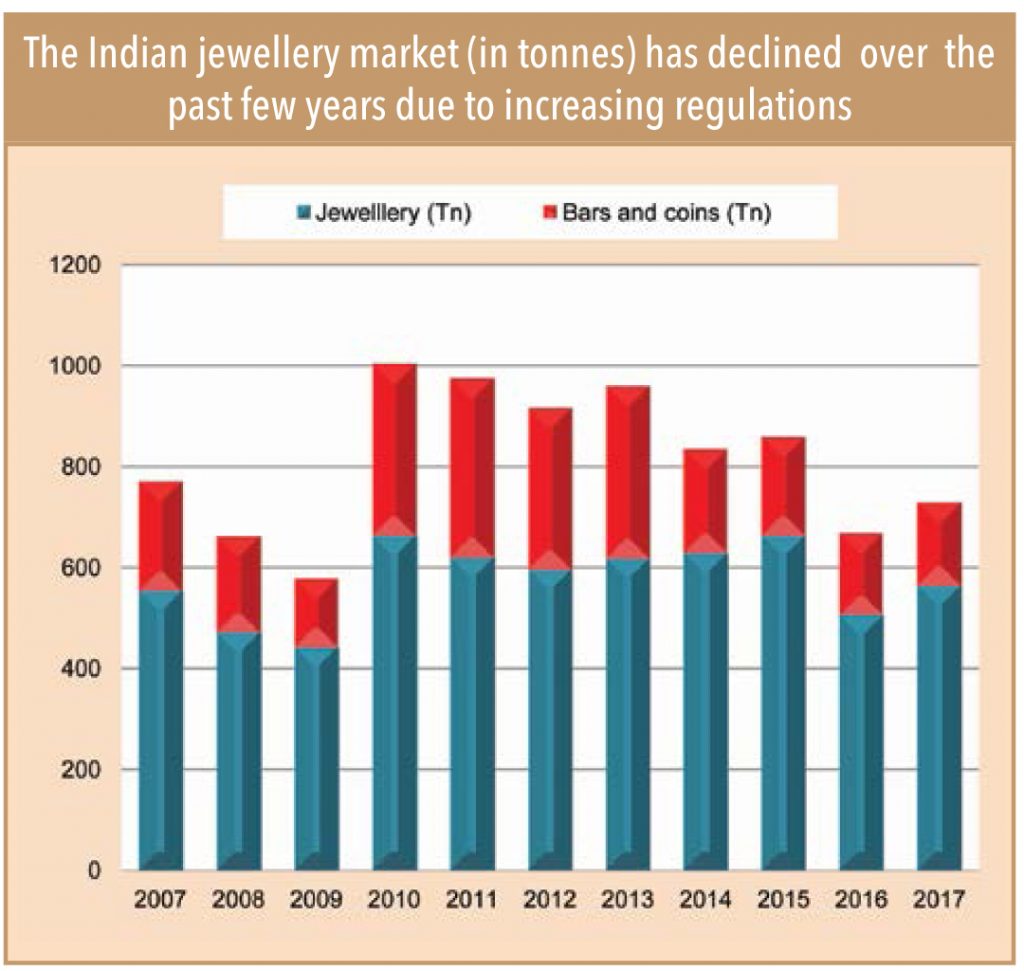

India’s US$ 50bn jewellery sector has seen turbulence over for the past five years, as the government tried every trick in its book to reduce Indians’ obsession with gold in order to reduce the flow of unaccounted money into this sector. The government has partially succeeded in curtailing gold consumption (gold demand reduced by 20% over the past five years) through various measures including PAN card disclosure. Due to this, the jewellery industry has not been able to grow to its true potential. However, of late, organised players are seeing healthy growth as the government backs its mandate of formalisation with demonetisation, GST, and hallmarking (to be implemented soon). These measures have led to customers switching to organised jewellers, who offer the advantages of contemporary design, lightweight jewellery, and most importantly, trust.

Meanwhile, unorganised players are facing problems such as their money-lending businesses (significant contributor to profitability) being under pressure, non-availability of gold-on-lease, and limited capital availability, which restricts their ability to invest into their businesses for growth. Their next generations’ flagging interest in running the show and increasing family feuds are also major drawbacks.

Organised players have taken a decisive lead over unorganised players via the introduction of differentiated design backed by their path-breaking ad campaigns and celebrity endorsements, gold-exchange programmes offering lower deductions and high caratage, and large-format stores. Additionally, the new generation of karigars (artisans or artists) are more inclined to work for organised players as they provide better salaries, food, accommodation, and other facilities such as schooling for their children. In contrast, unorganised players have a long history of exploiting these karigars.

There are some structural challenges to contend with as well – today, young adults prefer collecting ‘experiences’ rather than accumulating assets. However, this could be an urban-India phenomenon, that too within a certain segment of the younger generation. Gold is so deeply entrenched in the daily life of Indians that it is unlikely that the jewellery industry will suffer any significant slowdown anytime soon. However, like every other industry, it is changing inexorably. While small unorganised jewellers have an edge in some areas – such as in terms of exchanging gold where customers do not want to pay GST and managing threshold limits under various regulatory acts – these benefits seem transient and will fade once the government increases surveillance. Overall, the advantages are piled high on the side of the organised players.

A glittering love affair!

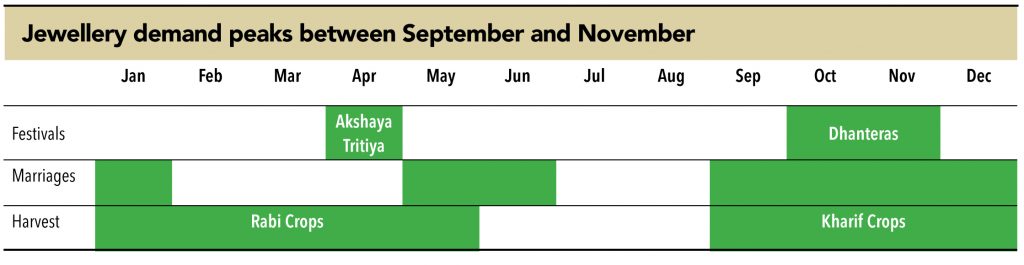

Indians know and love their gold, always have, always will. The Mahajanapadas, the sixteen kingdoms of ancient India from the 6th to 4th centuries BCE, used to trade in minted punch-marked silver coins in 600 BC and India was one of the first countries in the world to transition from barter system to a money-based trade system, along with the Greeks. During 1-1000 AD, India was the world’s largest economy and trade was conducted using gold coins and bars. However, India’s love affair with gold has chiefly centred around jewellery, which is interwoven into the very fabric of its society. Whether it is Raksha Bandhan in north India or Onam in the south, or Akshay Tritiya and Diwali all over the country, people buy gold to mark new beginnings, births, festivals, and weddings. In fact, the World Gold Council estimates that more than 50% of Indian demand for gold is wedding-related. Even today, India’s gold stock almost equals the market cap of Apple, the world’s largest company in value terms.

Deep-rooted: India’s obsession with the yellow metal!

As per the World Gold Council, Indian households own 23,000 -24,000 tonnes of gold (valued at >US$ 800bn), which is almost equivalent to the market capitalisation of Apple, the world’s largest company in terms of market cap. Additionally, Indian temples own around 3,000-4,000 tonnes of gold, which is offered to the temple deities by devotees. India consumes 700-800 tonnes of gold annually, with purchases driven by tradition, festivals, and other important family and social occasions. In some communities in India, gold is even handed out on someone’s death!

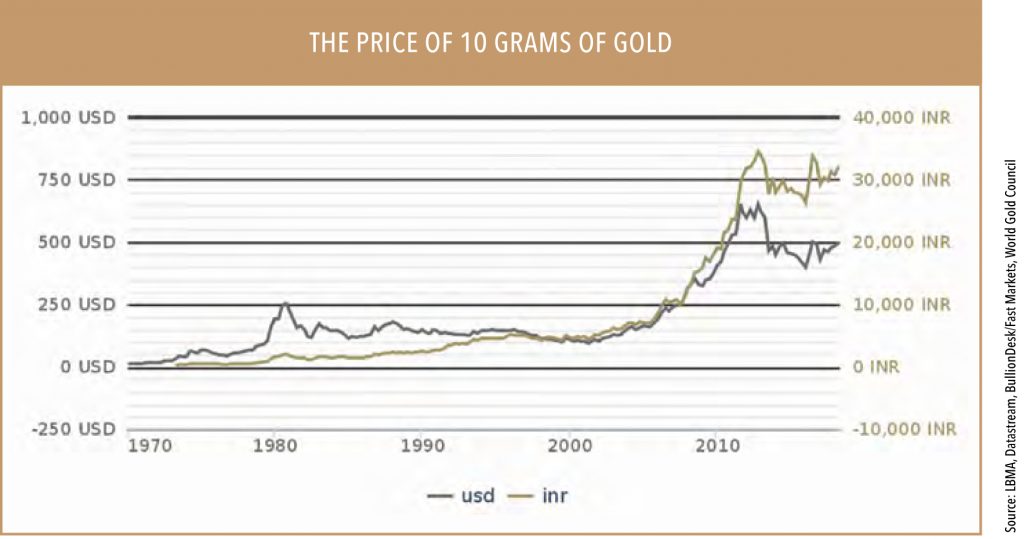

The Indian obsession with gold remains never-ending, despite more than a 7x increase in gold price between 2000 and 2017. This is because gold is deeply rooted in India’s culture. Wedding jewellery demand (constituting more than 50% of jewellery demand) remains firm. Buying gold jewellery for an Indian bride is based on the concept of streedhan – loosely translated as the property that a woman should receive at the time of her marriage, in the form of ‘bride security’; technically, it is hers to keep.

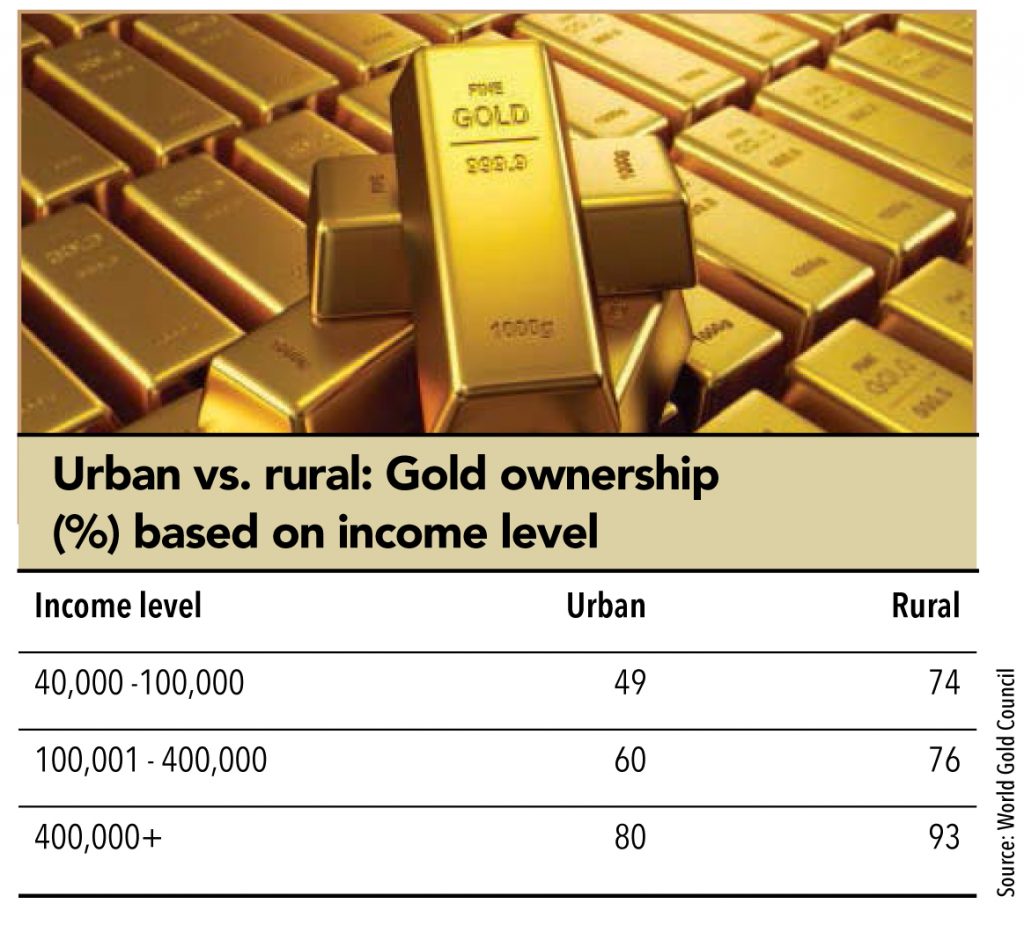

Higher ownership in rural India, which tends to rise with income levels

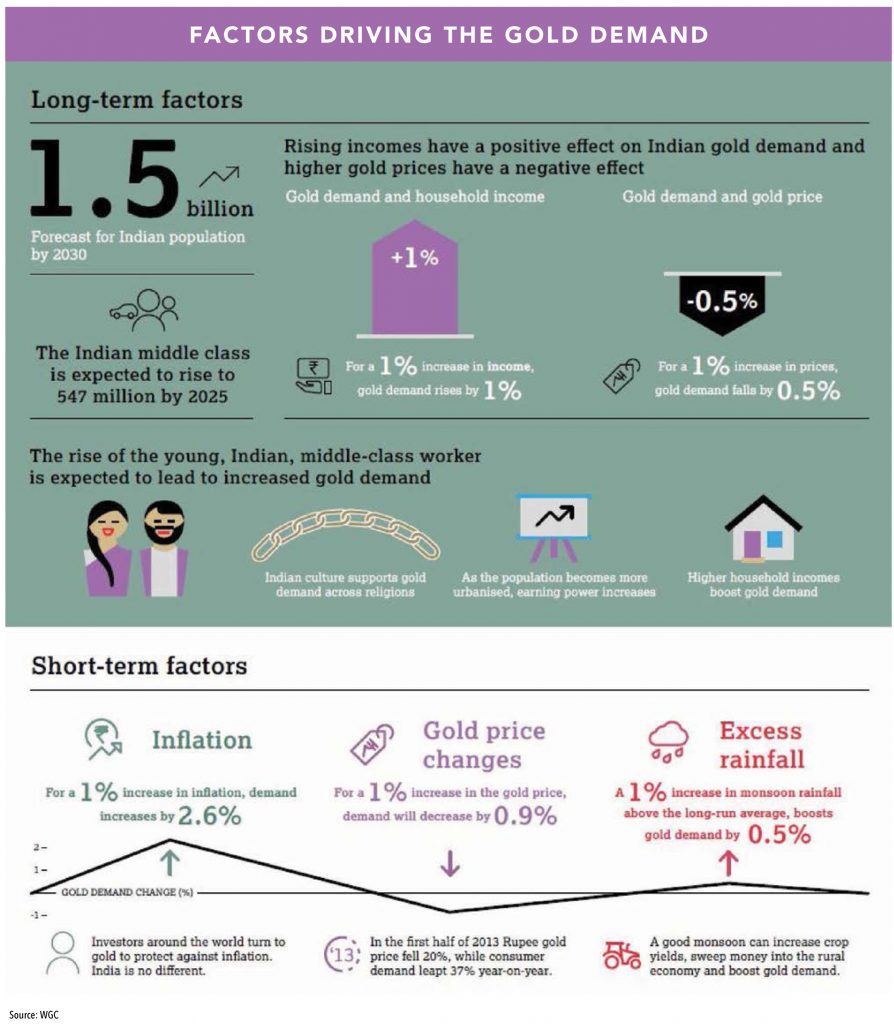

Rural India (where 70% of India’s population resides) invests its savings in gold/jewellery due to lack of access to banking facilities and the yellow metal’s high liquidity. Good harvest along with the wealth effect (increasing land and gold prices) drives rural demand, whereas improved economic sentiment (better job opportunities), an increasing middle-class, and urbanisation drive urban demand.

Arun, 18, a waiter at Sri Ganapathy Hotel in Coimbatore, earns 6000 per month. He has been saving 2,000 per month for a while so that he can give gold jewellery to his sister when she gets married.

This kind of consumer behaviour is striking and speaks volumes about India’s culture, not only in terms of the importance of gold, but also in terms of the importance of these cultural obligations trumping personal desires. It is amazing that at such a young age, this young man, instead of spending on activities that bring him pleasure, has started saving for purchasing jewellery for his sister. In south India in particular, there is a greater inclination towards gold and this region constitutes 40% of India’s total gold demand.

“Organised players are taking away business from smaller players now. Better pricing, guarantee (for every purchase), third-party purity certification, and services such as free repairs and appropriate buyback options swing business in favour of organised players.”

– Joy Alukkas, Chairman of the leading eponymous chain from Kerala

An inexorable shift towards organised

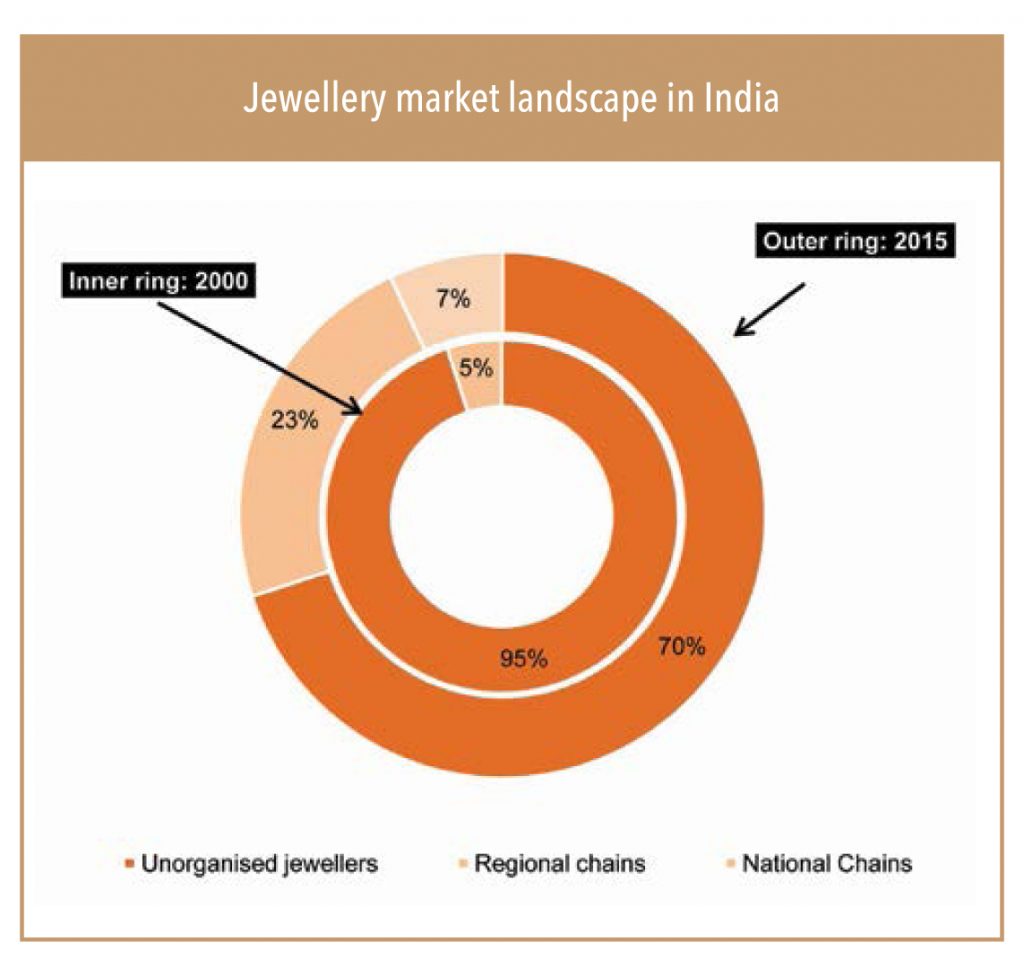

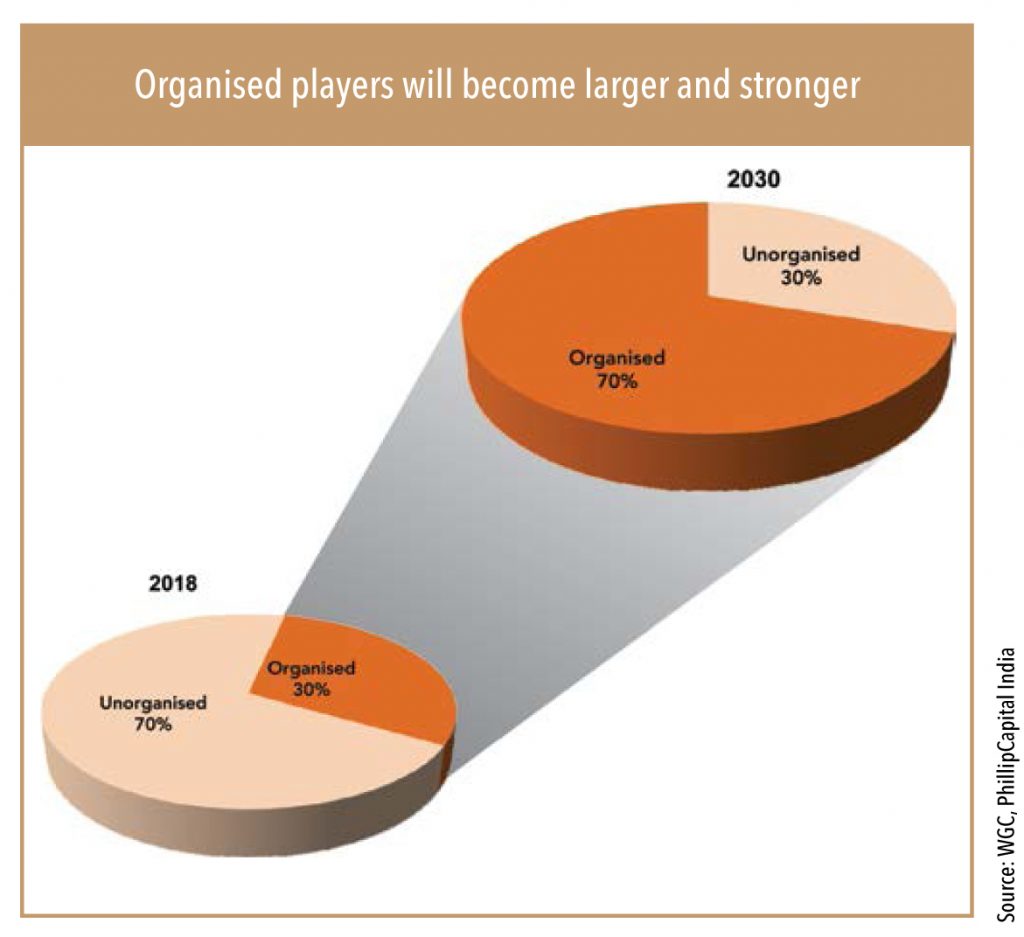

Despite its enormous potential (` 3,000bn annual jewellery sales), the Indian gold jewellery retail industry continues to remain highly fragmented. Small unorganised jewellers still command a lion’s share of the market at 70%, but they have lost considerable share to organised players. Now, the market has three kinds of participants – unorganised, organised regional players, and national players. Regional and national players have been able to increase their market share to 30% in 2015 from just 5% in 2000 based on network expansion, differentiated designs, and providing customers with the best-in-class hallmarked jewellery thereby garnering customers’ trust.

All industries are moving towards formalisation, jewellery is no exception

Stock markets have been most bullish about the formalisation theme – and sectors such as brick and mortar retail, jewellery, home-building material, and consumer durables/appliances hold the maximum potential for formalisation. Incrementally, the government is trying hard to ensure that more sectors join the formal economy via GST implementation, which ensures an audit-trail of all transactions. Out of India’s 500mn workforce, 90% is deployed in the unorganised sector and is deprived of social security benefits and minimum wages. In order to encourage formalisation, the government is planning to make a 12% contribution towards employees’ provident funds for the next three years for all new jobs across sectors. Retail (US$ 600bn) and jewellery (US$ 50bn) have the maximum growth potential, given their size and higher share of unorganised players.

“When there is suspicion, the industry suffers. Consumers want to go to a safe haven, as in a safe place to buy, like Tanishq. They want to buy clean gold rather than buy gold in cash.”

– Bhaskar Bhat, Managing Director, Titan.

Troika pushing customers to organised players, led by hallmarking

Organised jewellers have a long run ahead, as they steadily and rapidly gain market share from unorganised players. The troika – compulsory hallmarking, increased regulations (GST implementation), and structural issues are likely to accelerate this shift in coming years. Structural issues include low-cost gold on lease not being available to unorganised players, their money-lending businesses (at times almost half of their profit comes from this) being under pressure, and their next generation’s disinterest in running small business.

Compulsory hallmarking will be another turning point. There is already a trust deficit as far as unorganised jewellers are concerned. When hallmarking becomes compulsory, it will act as even more of key catalyst for the momentum accelerating to the organised sector, because the unorganised sector’s advantage of under-karating will disappear, which in turn will force them to increase making charges.

“Buyers with clean money would not want to associate with small, unorganised players anymore. They are moving to organised retailers now, as small, one-shop jewellers are not even able to provide payment options such as digital pay-ins, RTGS, or cheques. Informed buyers insist on ‘hallmark’ — a gold purity certification in accordance with Indian Standards specifications.”

– Surendra Mehta, National Secretary, India Bullion and Jewellers Association.

Hallmarking is already haunting smaller jewellers

Pratik Jain, 35, runs a shop called Kshitij Jewellers (name changed) in Andheri, a western Mumbai suburb. His family has been in this business for more than 40 years. However, he is not a happy man at the moment. “Musibatton ka pahaad toot pada hai hamare dhande par (a mountain of worries has crashed down on our business),” he lamented, as the government’s focus on increasing awareness about hallmarking has led to more customers preferring hallmarked jewellery. “We are forced to stock hallmarked jewellery – it will become mandatory in time,” he mused.

Jain openly acknowledged that currently, most small jewellers resort to ‘under-karating’ of jewellery (i.e., selling gold that is of a less karat than claimed). Apart from demonetisation, GST implementation, Pan Card regulation, increased competition from gold-loan NBFCs/fin-tech companies in money lending, hallmarking will the last nail in the coffin that will “make sure business profitability goes for a toss,” said Jain.

Can organised players become dominant by 2030?

The World Gold Council expects the share of organised players to increase to 40% in 2020 from 30% in 2015 due to a combination of factors. It is likely that after 10 more years, organised players command a dominant market share due to the limited ability of unorganised players to match their might and scale.

A small Mumbai jeweller openly acknowledged that jewellers of his size resort to under-karating, i.e., selling jewellery and other gold retail products that are less pure than what they should be

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access