Mr Sanjay Shah, the chairman and managing director of DBS Affordable Housing Strategy, in his book ‘Pursuit of Affordable Housing’, mentioned that the development of affordable housing by a private player is all about cash flows, volume, and passion – managing cash flows to complete construction and delivery on time, producing enough units to break even, sustaining in the market, and a passion to serve lower-income people against all odds – form the core of this business, he believes.

He goes on to say that, “There are many ways in which the affordable segment is fundamentally different. It has a lower rate of return due to low appreciation in the prices of units. A Rs 1mn dwelling is not likely to appreciate to Rs 2mn, because then it stops being affordable. Even if does appreciate, people with a capacity to purchase a Rs 2mn unit are unlikely to be compatible (socially and economically) with the people already residing in such housing. Appreciation in the real estate market is a different story altogether. Construction of a signature, ‘limited edition’ society in a posh area will ensure unlimited appreciation. This is the basic difference between regular real estate businesses and affordable housing.”

Apart from a perception challenge, affordable housing also involves challenges related to supplying houses at a really ‘affordable’ cost, especially within city limits.

Some of the most common constraints that make houses unaffordable are:

Unavailability of land in urban areas

In urban areas, high population density has triggered huge demand. In such high-cost areas, the number of projects completed or under construction (such as Maharashtra and Delhi) tend to be low, suggesting that availability of adequate land is a must. Reports by various consultancy firms suggest that without the government’s support, limited availability of land in urban areas makes it unviable for developers to take up affordable housing projects. A KPMG report on the urban housing shortage in India says that substantial non-marketable urban land that government-owned entities (such as railways) own, can be used more efficiently – a number of such land parcels are in centrally located areas. Through better monitoring, authorities can make more optimum use of these land parcels and prevent the on-going proliferation of slums and squatter settlements in these areas.

Delays in approvals and permission

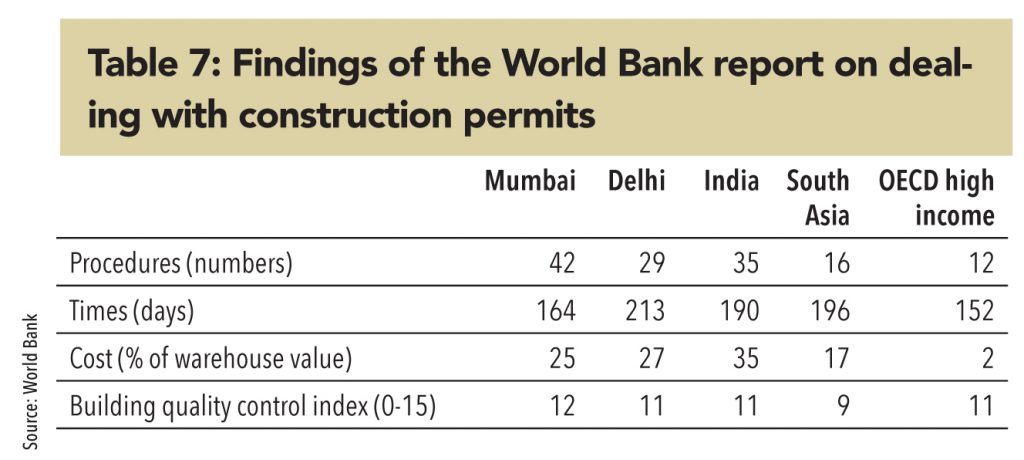

Even though real estate and housing contribute significantly to India’s economic growth, the sectors have “peculiar complexities that arise from uncertainties, inter-dependencies, and inefficiency in the operations of various process workflows and authorities,” says a study by KPMG and NAREDCO. The building approval process in India is relatively slower and more expensive than in vs. several other countries. In India, various types of approvals are required at different stages by different authorities.

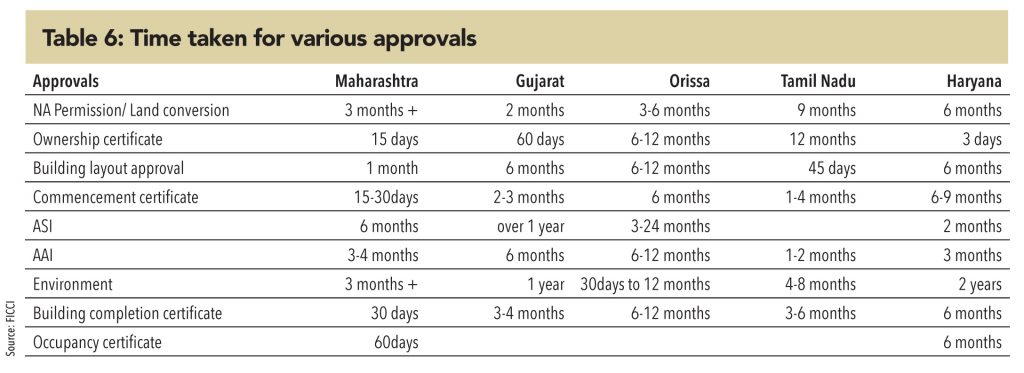

The KPMG-NAREDCO study says, “Development authorities allocate approvals based on land use and zoning regulations, while municipal corporations are responsible for the enforcement of building regulations as stipulated by the ‘NBC’. Additionally, several non-planning permissions are also required to be obtained from various authorities such as the Traffic and Coordination Department, Airport Authority of India (AAI), Coastal Regulatory Zone (CRZ) authorities etc., as an assurance that buildings do not adversely affect their surrounding areas. Permits are also needed from utilities departments such as water and sewerage departments, electricity boards, etc.” A FICCI research report titled ‘Streamlining Approval Procedures for Real Estate Projects’, which surveyed five states, suggests that in India, it takes anywhere between 2.5-4.0 years, on an average, to receive necessary building approvals.

As per the ‘World Bank Group Report – 14’, in terms of ease of dealing with construction permits, India is #185 in a ranking of 190 economies. The report highlights that in India, an average of 35 procedures are needed over a period of 190 days for obtaining construction permits (12 approvals over an average of 152 days in the OECD region, 16 approvals over an average of 196 days in the South Asia region).

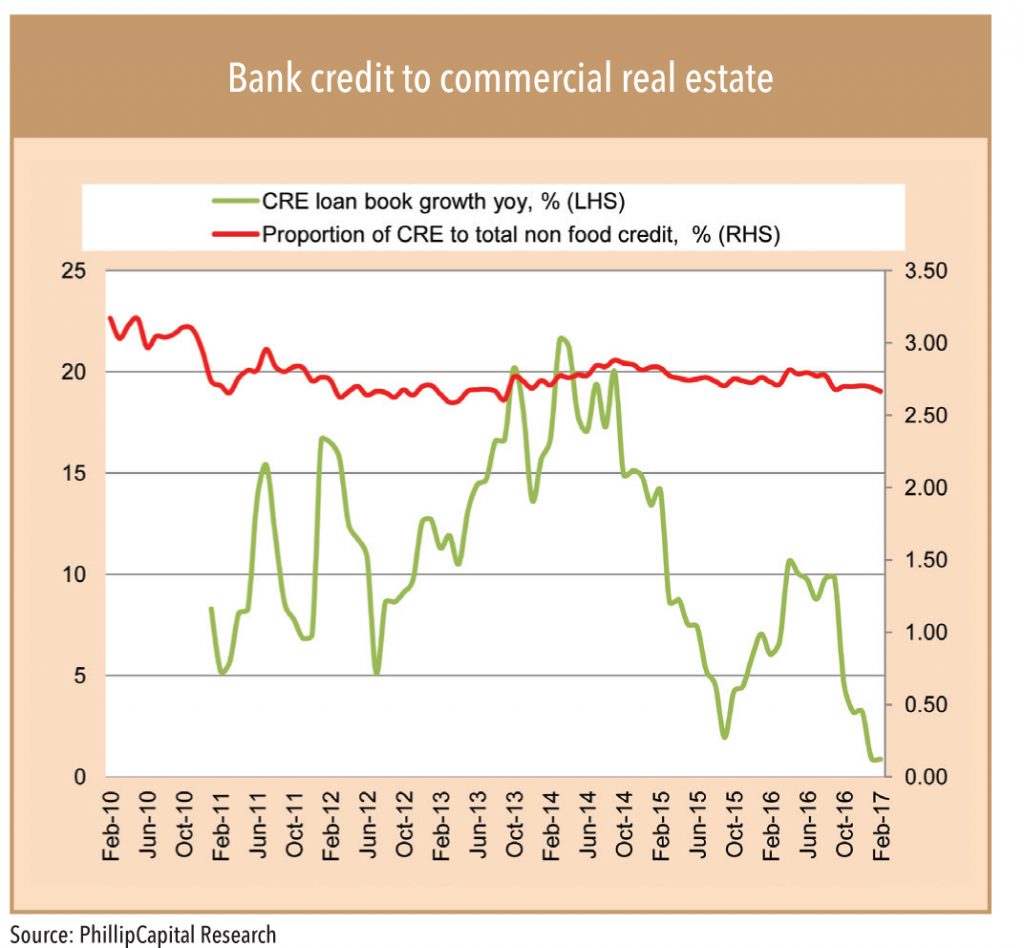

Poor fund availability to builders

Real-estate developers are grappling with funding challenges. Banks have curtailed their exposure to real estate (citing caution), leaving the developer segment with high-cost finance options such as Non-banking Financial Companies (NBFCs) and Private Equity (PE) funding. Moreover, the high cost of finance, coupled with waning demand, has disrupted developers’ cash flows, leading to deferred project launches and a change in the slated supply. For affordable housing developers, the funding situation is even grimmer.

Targets urban areas with following components/options for states/union territories and cities:

• Rehabilitation of slum dwellers with participation of private developers using land as a resource

• Promotion of affordable housing for weaker sections through credit-linked subsidy

• Affordable housing in partnership with public and private sectors

• Subsidy for beneficiary-led individual house construction or enhancement

Features

• Central grant of Rs 100,000 per house, on an average, available under the slum rehabilitation programme. State governments would have flexibility in deploying this grant to any slum rehabilitation project (that uses land as a resource for providing houses to slum dwellers).

• Under the Credit-Linked Interest Subsidy component, an interest subsidy of 6.5% (on housing loans up to a tenure of 15 years) will be provided to EWS/LIG categories, wherein the subsidy payout on an NPV basis would be about Rs 230,000 per house, for both categories.

• Central assistance at the rate of Rs 150,000 per house for EWS will be provided under ‘affordable housing’ in partnership and beneficiary-led individual house construction or enhancement.

• State governments or urban local bodies (like housing boards) can take up affordable housing projects to avail the central government’s grant.

• Will be implemented as a Centrally Sponsored Scheme except the credit-linked subsidy component, which will be implemented as a Central Sector Scheme.

• The mission prescribes certain mandatory reforms for easing up the urban land market for housing, to make adequate urban land available for affordable housing. Houses constructed under the mission would be allotted in the name of the female head of the households or in the joint name of the male head of the household and his wife.

• The scheme will cover the entire urban area consisting of 4,041 statutory towns with an initial focus on 500 Class-1 cities and it will be implemented in three phases:

o Phase-I (April 2015 – March 2017) to cover 100 cities to be selected from States/UTs as per their willingness.

o Phase – 2 (April 2017 – March 2019) to cover additional 200 cities.

o Phase-3 (April 2019 – March 2022) to cover all other remaining cities.

• However, there will be flexibility in covering number of cities in various phases and inclusion of additional cities may be considered by the Ministry of Housing & Urban Poverty Alleviation in case there is demand from states and cities, and there is capacity to include them in earlier phases.

• Credit-linked subsidy component of the scheme would be implemented across the country in all statutory towns from the very beginning.

Implementation:

• Dimension of the task at present is estimated at 20mn houses. However, the exact number of houses would depend on a demand survey, for which all states/cities will undertake a detailed demand assessment and assess actual demand by integrating Aadhar number, Jan Dhan Yojana account numbers, or any such identification of intended beneficiaries.

• A Technology sub-mission under the Mission would be set up to facilitate adoption of modern, innovative, and green technologies, and building material for faster and quality construction of houses. It will:

o Facilitate preparation and adoption of layout designs and building plans suitable for various geo-climatic zones.

o Assist states/cities in deploying disaster resistant and environment friendly technologies.

o Will coordinate with various regulatory and administrative bodies for mainstreaming and up-scaling deployment of modern construction technologies and material in place of conventional construction.

o Coordinate with other agencies working in green and energy efficient technologies, climate change, etc.

o Will also work on the following aspects: (1) design and planning, (2) innovative technologies and materials, (3) green buildings using natural resources, and (4) earthquake and other disaster resistant technologies and designs.

In the spirit of cooperative federalism, the mission will provide flexibility to states for choosing best options among the four verticals of the mission, to meet housing demand in their states. The process of project formulation and approval in accordance with ‘mission guidelines’ would be left to the states so that projects can be formulated, approved, and implemented faster. The mission will provide technical and financial support in accordance with the ‘guidelines to the states’ to meet the challenge of urban housing.

The mission will also compile best practices in terms of affordable housing policies of the states/UTs designs and technologies adopted by states and cities with an objective to spread best practices across states and cities, and foster cross learning. The mission will also develop a virtual platform to obtain suggestions and inputs on house design, materials, technologies, and other elements of urban housing.

Central and state grants and incentives + local bodies

In order to incentivise borrowers and generate demand for housing, Government of India has provided various incentives and grants. For the EWS segment, it provides a (per dwelling) central grant of Rs 150,000 where the unit cost is around Rs 500,000. Apart from the central government, state governments and urban local bodies have various schemes with grant amounts of Rs 150,000-250,000. Due to the existence of both central and state grants, the beneficiary contribution tends to be minimal or nil in the EWS segment.

In order to incentivise the LIG and MIG segments, the government launched the credit-linked subsidy scheme (CLSS). It provides an interest subsidy of 6.5% in the LIG segment for loans up to Rs 600,000. Similarly, the interest subsidy available for MIG-1/2 (MIG 1: Household income Rs 0.6-1.2mn; MIG 2: Rs 1.2-1.8mn) is 4%/3%. The present value of the subsidy amount is reduced from the principal component, which brings down the cost of the dwelling unit. For the LIG segment, the subsidy benefit for a dwelling unit costing Rs 1.8mn translates to 14%. Similarly, the average benefit in MIG-1/2 works out to 7%/4%. Income tax benefits provided to home-loan borrowers, along with subsidy schemes, brings down the effective interest costs of home loans to as low as 2.4% for LIG, which is similar to rental yields in India, while for MIG-1/2, the costs come to 3.8%/4.4%.

Under CLSS, the present value of the subsidy amount is reduced from the principal component, which brings down the cost of the dwelling unit

The success stories globally in affordable housing have some things in common, which can be well replicated in India. Land has always being an issue within city limits. In most of the global success stories, the government has made land available. In India, today, government or semi-government bodies (such as railways, defence, and state transport authorities) own large land parcels. These land parcels can be effectively used for affordable housing at low costs. Similarly, there is a concept of rental homes provided by local authorities, which would help address the issue of down payments. Redevelopment of existing slums is a major hurdle in cities such as Mumbai due to relocation policies. Therefore, a welcome move would be policies (such as higher FRA/FSI) that support redevelopment without too much inconvenience to developers.

Singapore affordable housing:

The government develops and manages a large part of the residential housing in Singapore. Around 75% of the housing stock in the country is built by The Housing & Development Board (HDB), Singapore’s public housing authority. The primary objective of HDB is to provide affordable housing for the poor. The purchase of these flats is financially aided by the Central Provident Fund (CPF). Because of effective policies, the country’s home ownership rate at 90% is one of the highest globally. Currently, Singaporeans who have a family income of less than SG$ 12,000 a month qualify for an apartment. Among resident employed households, the 2014 median household income from work was SG$ 8,292 per month. The median house type is a four-room flat sold by the Housing & Development Board (HDB), on a 99-year leasehold basis.

Government provides support for HDB in the form of: (1) annual grants from the current budget to cover its deficits incurred for development, maintenance, and upgrading of estates, (2) loans for mortgage lending and long-term development purposes, and (3) land allocation for HDB housing and comprehensive HDB town planning. The Singapore affordable model has been a great success – 82% of the resident population lived in such accommodation as on 31 March 2015. The HDB brought about a transformation on the housing-supply side, leading to higher homeownership rates, which doubled to 59% in 1980 from 29% in 1970 and reached 90%+ in 2017.

Eligibility criteria for various dwelling types

• HDB rental and direct purchases are restricted to citizens, with current monthly gross household income caps at SG$ 1,500 for rental and SG$ 12,000 for direct purchase, respectively.

• The Executive Condominium scheme, a hybrid public–private housing scheme for citizen households, has a household income cap of SG$ 14,000.

• The resale HDB sector is available to citizens and Singapore permanent residents (SPRs). However, HDB housing grants are made taking into account citizenship, marital status, and household income of purchaser households.

• The private housing sector is dominated by transactions of higher-income Singapore citizens, SPRs, expatriates, and foreign investors.

Central Provident Fund used as a vehicle for housing finance

• In 1968, the government allowed withdrawals from the CPF fund to finance the purchase of housing sold by the HDB. Both employers and employees contributed a certain share of the individual employee’s monthly salary toward the employee’s personal and portable account in the fund. When the CPF was established in 1955, the contribution rate was 10% (5% each by employees and employers) of the monthly salary. These rates were raised gradually to 25% of wages in 1984. At present, these are 20% of salary for employees and 17% of salary for employers, up to a monthly salary ceiling of SG$ 6,000.

Singapore follows a progressive subsidy and tax structure – wealthy property owners and investors are taxed and the receipts are used to subsidise homeownership of lower-income groups.

Hong Kong affordable housing

The Hong Kong Housing Authority (HKHA) and The Hong Kong Housing Society (HKHS) are two statutory bodies that are responsible for implementing most of Hong Kong’s public housing programmes. Hong Kong’s Long-Term Housing Strategy (LTHS) has three major directions:

• To build more public rental housing (PRH) units and to ensure the rational use of existing resources; these units are rented at discounted rates to low-income residents

• To provide more subsidised sale flats, expand the forms of subsidised home ownership, and facilitate the market circulation of existing stock. These categories of houses are assigned for sale to low-income qualifiers at prices that are significantly lower than market value, and the land value is similarly subsidised. The mortgage and resale of these units in the second-hand market are likewise restricted to eligible low-income residents.

• To stabilise the residential property market through steady land supply and appropriate demand-side management measures, and to promote good sales and tenancy practices for private residential properties.

As of 31st March 2016, about 30% of the population lived in PRH flats and 16% lived in subsidised sale flats; the rest 54% were residing in private permanent houses. Because of the focus on rental housing, home ownership rate in Hong Kong remained relatively lower at about 50%.

Shanghai affordable housing

The Shanghai affordable housing model is based on four approaches:

• Low-rental housing for extremely poor families who otherwise find it difficult to be included in the formal housing sector

• Public rental housing for the working population with stable incomes

• Shared ownership housing with the government

• Housing for those who need to be relocated from their old shaky buildingsShanghai has set up a housing provident fund to fund low-cost housing. The government introduced the Housing

Shanghai has set up a housing provident fund to fund low-cost housing. The government introduced the Housing Provident Fund in Shanghai in 1991, requiring all employees of state-owned enterprises to contribute a proportion of their salaries to the fund – with employers contributing a similar amount. Workers are allowed to withdraw their savings from the fund when they retire; alternatively, they can use the money to purchase homes in the private housing market. They can also apply for low-interest loans from the fund to buy property. Because of the effective affordable housing policy, homeownership in Shanghai has more than doubled to 85% from 36% in 1997.

Economically affordable housing

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access