The GV team travelled across India and met key stakeholders of the detergent industry (distributors, washing machine OEMs, customers, washing technicians, and marketing executives) to understand what is driving premiumisation. India’s US$ 50bn consumer market story is littered with buzzwords such as ‘Demographic Dividend’, ‘Under-penetration’ and ‘Premiumisation’. While to some extent, the Indian consumer story has already played out, it is still miles away from its full potential due to hurdles such as adequate job creation, which mellows demand for aspirational and premium products. Two recent events – demonetisation and GST – have changed the consumer story and enabled organised FMCG players to flex their muscles and accelerate the process of premiumisation across categories.

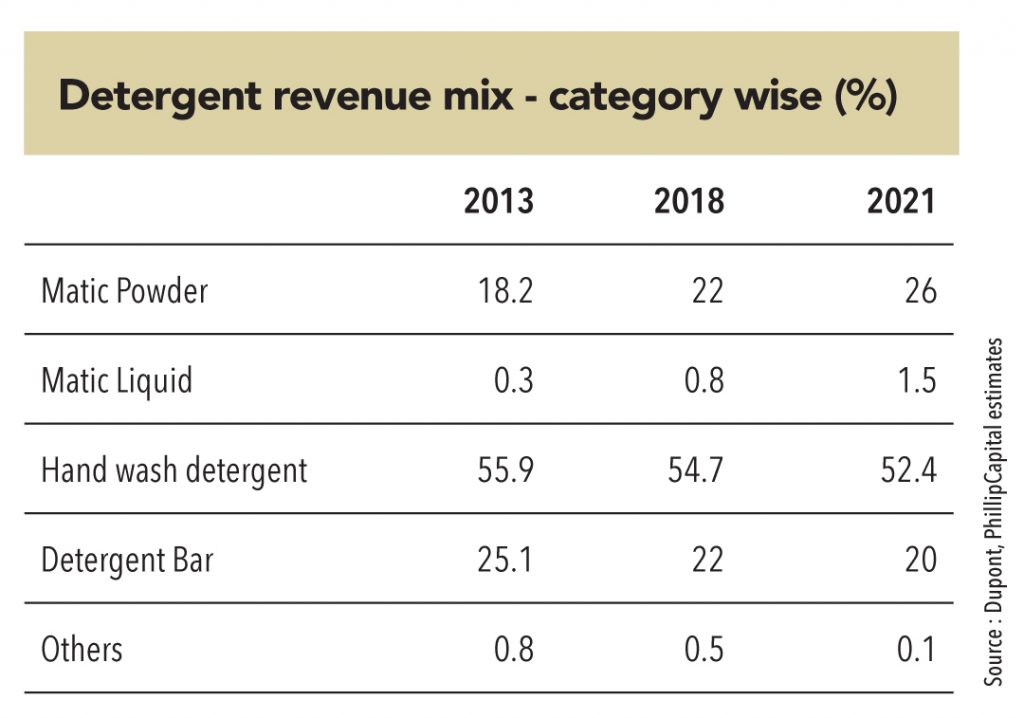

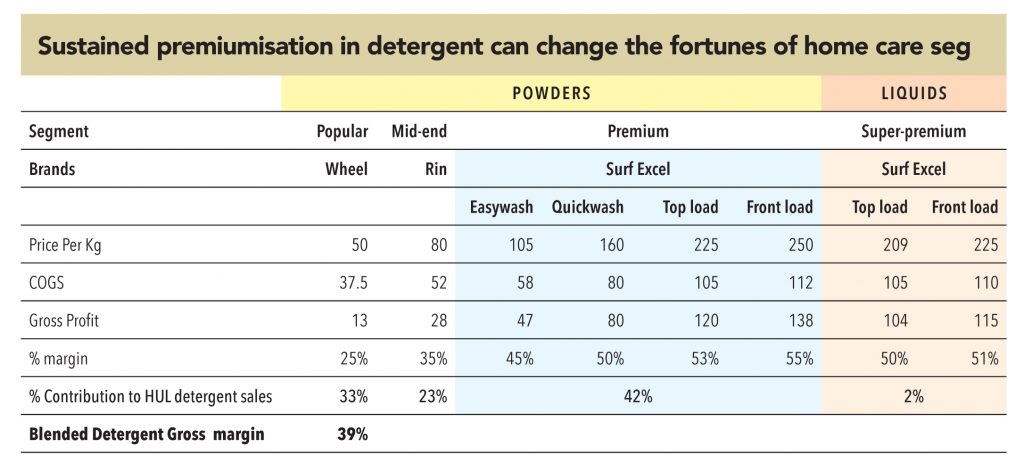

The Indian consumer remains highly value-conscious and will consume premium products only if they tick all boxes on price-value-proposition parameters. Premiumisation within detergents has taken a considerable lead over other FMCG categories, as customers find that these detergents offer the right bang for the buck. Consumers have already moved up from bars to powders over the past few decades, but FMCG companies are now trying to push them up the premium ladder a notch – to matics and liquids.

In general, things seem to be coming together for pushing premiumisation along to the next level – increasing penetration of automatic washing machines, easy financing of machines, hard-water problem aggravating not abating, higher household electrification, and development of superior formulated products that consume less water and cause less damage to the environment. FMCG companies are also getting their ducks in a row and working in close touch with consumer durables companies for product development, customer education, and innovation capabilities. Some consumer durables companies are even launching their own premium detergents, including laundry pods.

Challenges exist. Consumers are not easily opening up their wallets to purchase premium detergents and are finding ways (the great Indian jugaad) to make do with regular detergents. Another looming threat is technological innovation – what if making hard water soft becomes easy (premium detergent not needed) or waterless machines become viable at a retail level? To answer all these questions and more, this issue of Ground View delves into the squeaky clean world of detergents, checks how sustainable the premiumisation trend is, tries to get a feel of how customers perceive premium and normal detergents on the price-value chain, and also looks at challenges that FMCG companies might face in their premiumisation journey.

While people have moved from bars to popular detergents, there is still quite a ways before they adopt matics and liquid detergents

Awareness of detergents’ detrimental effects on hands and skin in rising

Locally manufactured products are believed to be very harsh on skin due to their high soda-ash content compared with branded products. As a result, most households in India – in rural areas and small towns – are moving to branded detergents. Those in semi-urban areas (tier 3-4 cities) have taken the lead in making a switch from bars to popular or mid-end detergents.

Kumud Gosrani, 48, lives in Chella village on the outskirts of Jamnagar City, Gujarat, home to the world’s largest petrochemical complex. She shifted to better quality detergents due to medical reasons. “I was diagnosed with a nail infection in 2015. The doctor told me to either use gloves while washing clothes (if I wanted to continue with my usual detergent) or to switch to a better quality detergent.” She says that once she started using branded detergents such as Wheel, she feels ‘comfortable’. “Better quality detergent (read national brands) improved my life. Not only do my clothes come out cleaner but my nails are getting better,” she said happily.

Others have made the shift because they are tired of the effort that has to be put in while using bars. Sujata Jain, 42, a native of Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh said, “I have moved on from using bars to Rin powder (mid-end product) as the effort needed to wash clothes with Rin is relatively lower and stains and dirt go away more quickly. Also, I think detergent is also more cost-effective on a per kg basis because bars dissolve fast. For my special clothes, I use Surf Excel small packs.”

Customer appetite for premium (or aspirational products) remains quite high. They get ‘hooked’ once these are made affordable (for e.g., available in Rs 10 sachets) and accessible (increased distribution reach)

Mrs Jain’s take is not entirely correct. Bars are actually more cost effective if customers are vigilant and wash clothes carefully. They have to apply detergent bars only on areas where dirt or germs are accumulated and rinse it off. Detergent powders clean the entire cloth, leading to more wastage. Of course, this logic does not work for people whose jobs entail more dirt accumulation on clothes – labour-intensive jobs such as labourers, office boys, and factory workers.

Top-end customers prefer powders over bars as the latter need a lot of time and manual effort, but bars could be the most efficient way to wash clothes

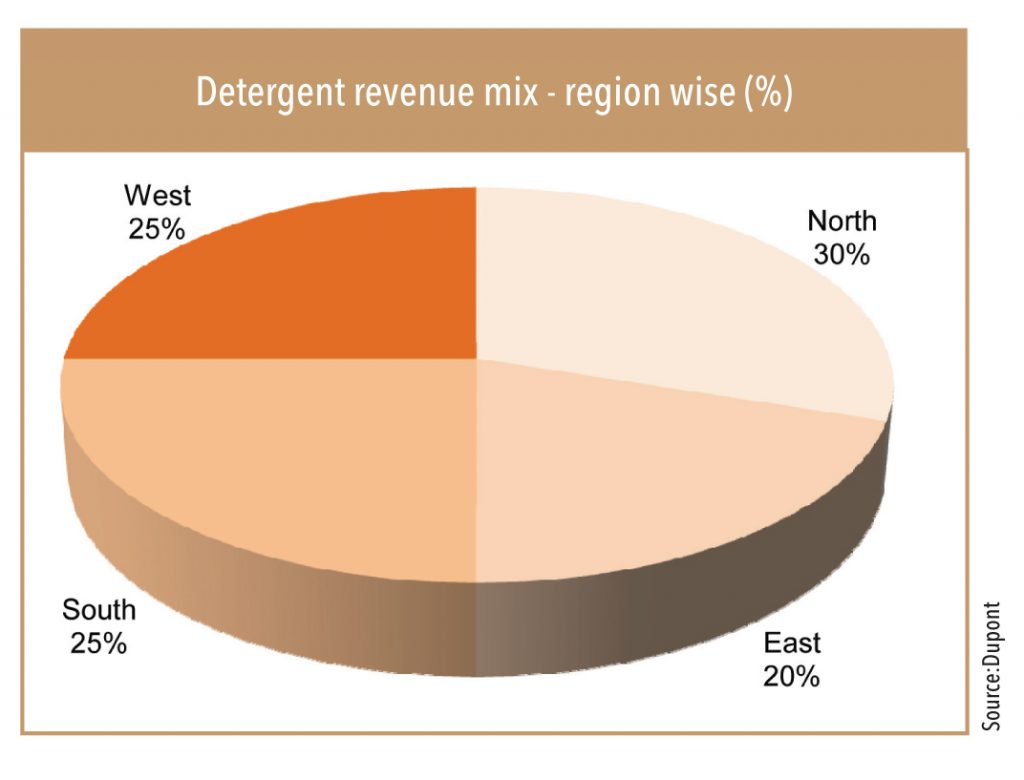

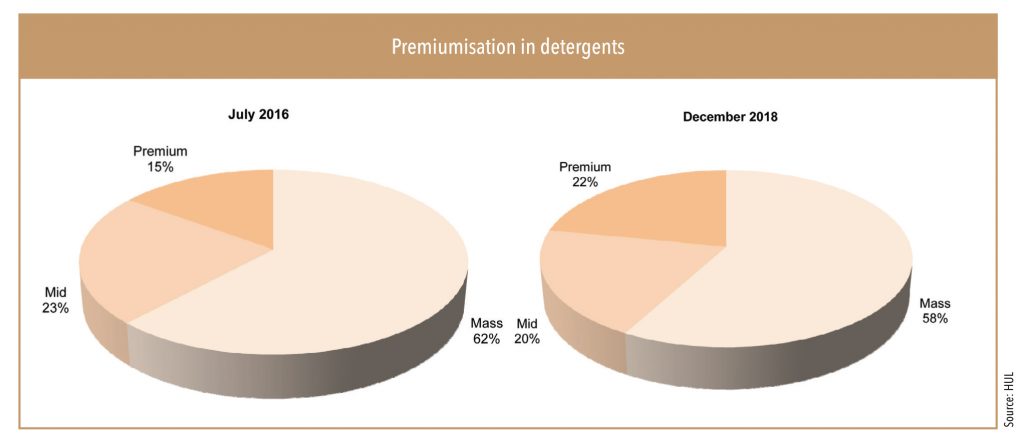

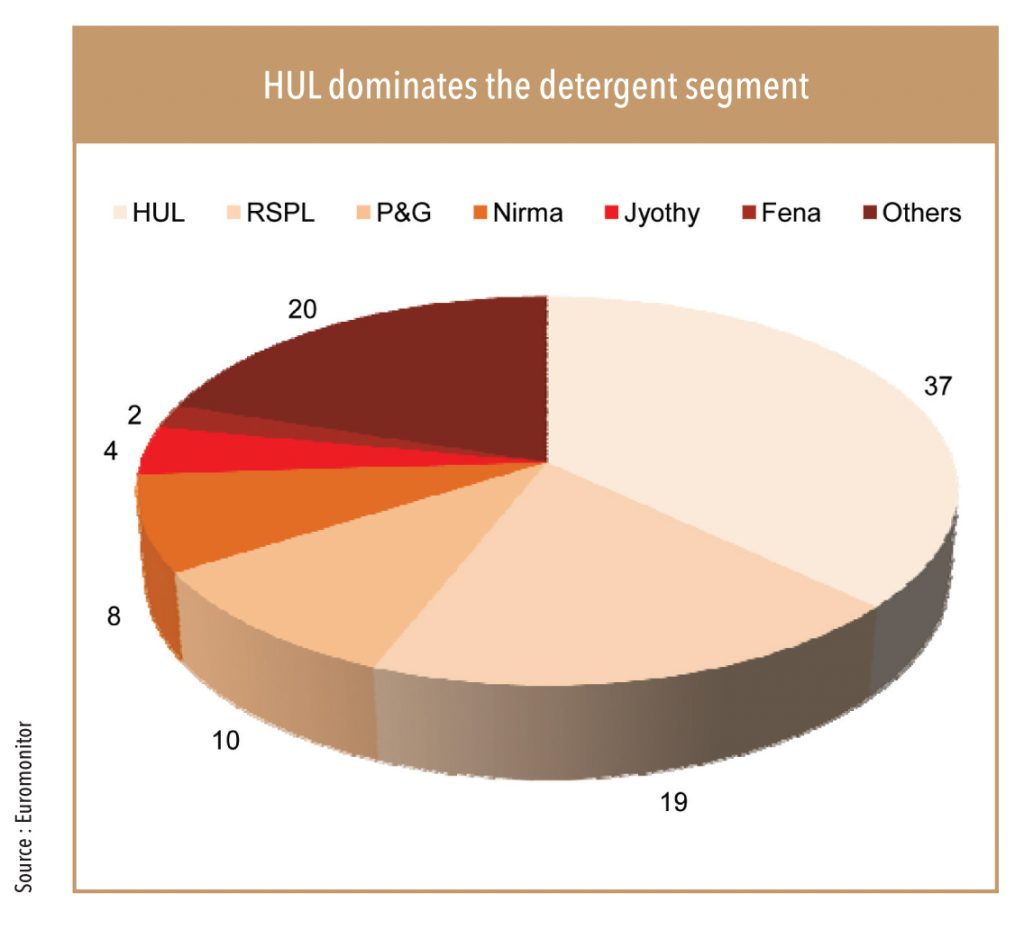

Competitive intensity continues to remain very high in popular detergents, which constitute much of the market (c.58%) in volume terms. Local players are strong in popular detergents – they are nimble, have a strong understanding about local taste and preferences, offer higher margin to trade channels, and are priced much more competitively than national brands. HUL and P&G dominate in premium and mid-tier detergents because of better-formulated products, customer affinity for consuming branded products in urban areas, and their extensive distribution network.

P&G – no longer looking at Tide bars for competing

A while ago, P&G shifted its focus away from the bar format (for the Tide brand) due to lower profitability in this segment. After its in-house manufacturing facility began, it restarted sales of Tide detergent bars, but with an objective to have a presence in the market rather than to compete.

Pre-GST and demonetisation – local players used to rule the popular segment

Before GST, many small and unorganised players held clout by evading taxes, knowing their own backyard, and distributing goods to local wholesalers – strongmen who liked to deal mainly in cash. HUL weakened in the mass (popular) segment as many unorganised players during 2014-16 used low crude oil prices to their advantage (LAB, a key raw material used to make detergents, is a crude derivative). In addition,two consecutive years of low monsoon and droughts (FY15-16) led to an increase in down-trading across FMCG categories, especially in rural areas – which hurt the growth of large organised detergent players that were not very strong in the popular detergent segment.

Even today, some local players continue to use their clout in their areas to sell the detergent of their choice. Sanjay Singh, a small shopkeeper in Satna, MP, said that he is forced to stock Mera Sangam – a local detergent powder in the popular segment. If he doesn’t, the manufacturer will not provide him stocks of Rajshree Pan Masala, a fast-selling high-margin product that the same company manufactures. “We somehow manage to sell these sub-par products (detergents available at Rs 30 per kg) to customers (despite knowing that its quality is far inferior to mainstream brands) by offering them freebies such as free buckets with the larger (mainly 5-kg) packs,” said Sanjay

GST + demonetisation has changed things quite dramatically for detergents

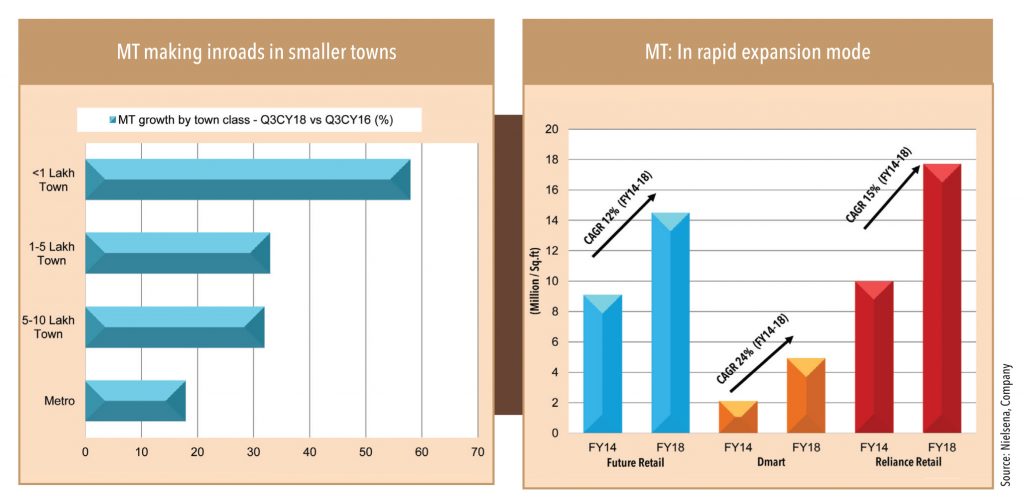

Over the past two years, things have changed for the better for pan-India branded players as strict GST compliance along with reduced availability of cash (after demonetisation) provided a more level playing field. Many consumers who moved to Modern Trade (MT)

Notably, in the last 2-3 years (after demonetisation and GST), premiumisation is no longer confined to metros and tier-1 cities. It has moved quite swiftly to tier-2 and 3 cities and MT players have aggressively expanded their reach in these areas

Pradeshfrom General Trade (GT) during demonetisation (after November 2016) have stayed with MT and have shown a higher propensity to consume premium and branded products across categories. With MT, customers got an opportunity to experience (touch and feel) premium products (matics and liquid detergents), which kirana stores were not interested in stocking due to lower customer pull. GT is usually more interested in stocking fast-moving popular and mid-category detergents.

The CMD of HUL, Sanjiv Mehta was quoted by a newspaper as saying – “We are seeing consumer demand or the off-take moving up as compared to the real lows that we saw in 2015 and 2016. Markets across urban and rural are seeing a positive trend.”

HUL passed on GST cuts to consumers at the premium end

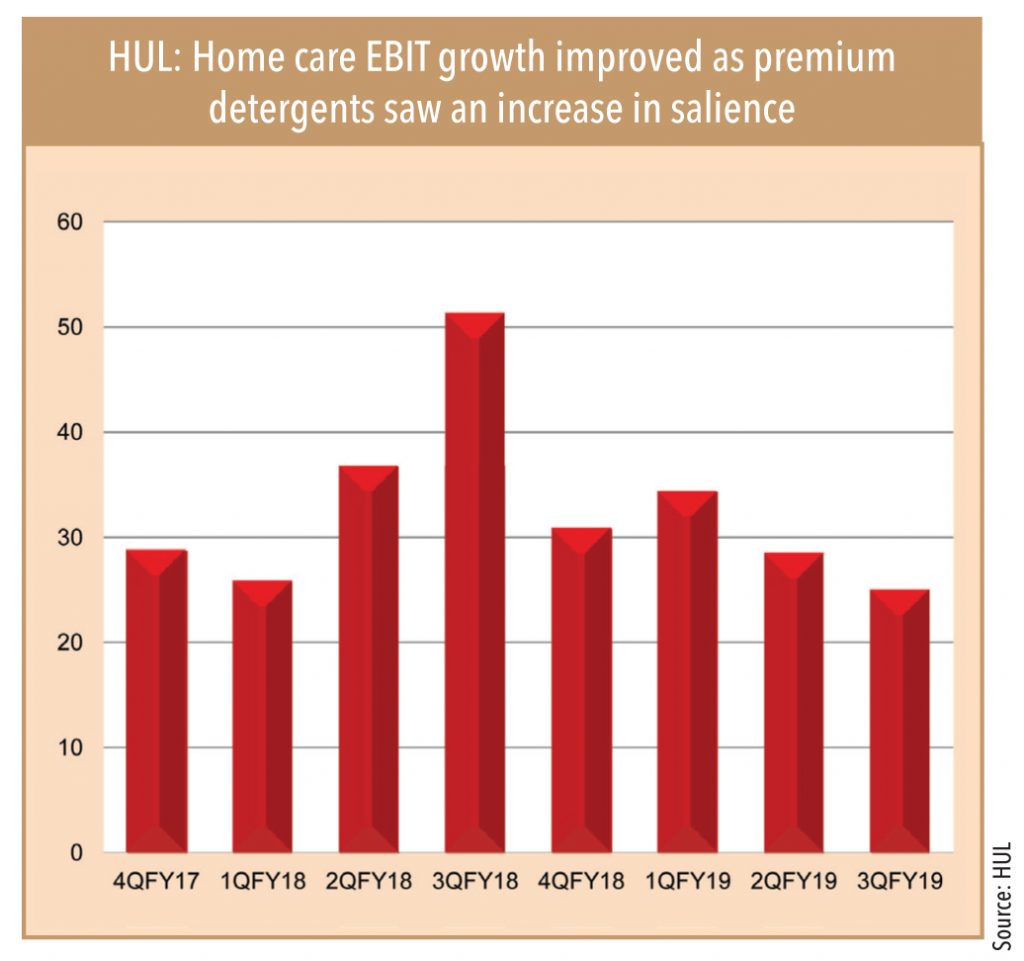

HUL used the opportunity provided by GST rate cuts to accelerate the process of premiumisation, but has taken a ‘portfolio approach’ while passing on GST rate cuts to customers. GST on detergents was reduced to 18% from 28% in November 2017. HUL reduced maximum MRP at the premium end of its portfolio (vs. the mass or mid-range end), thereby reducing the price difference between these products to some extent. This accelerated the process of premiumisation, which reflects in the EBIT growth of HUL’s home-care segment.

GST – needed in spirit, not just in letter

HUL’s profitability in home care can rise further if GST rules and regulations are implemented in spirit. If the E-Way bill (which governs interstate movement of goods) is properly implemented, it is highly likely that small and unorganised players will be forced to become fully compliant, thereby taking a hit on their margins due to higher cost of compliance. HUL will then be in a position to gain market share in the popular detergent segment, which has been its weakest link so far.

Wheel has been able to recover some of its lost ground after competition weakened (particularly Ghadi) after demonetisation and GST, which also led to HUL’s profitability in its home-care segment improving. Meanwhile, increasing focus on profitability led to P&G going slow on its low-margin products (Tide Naturals). Recent media articles indicate that HUL has significantly increased its efforts to check counterfeit products, which also helps to tilt the balance in its favour across segments in the detergents category.

Customers have shown a preference for branded consumer products over local products, even in the popular segment – if branded products are at a slight premium. This has been visible in paints over the past few quarters, when branded players showed decent growth in distempers (economy segment) after the GST rate was cut to 18% in July 2018 from 28%. This move led to the price difference between organised and unorganised players’ products shrinking substantially.

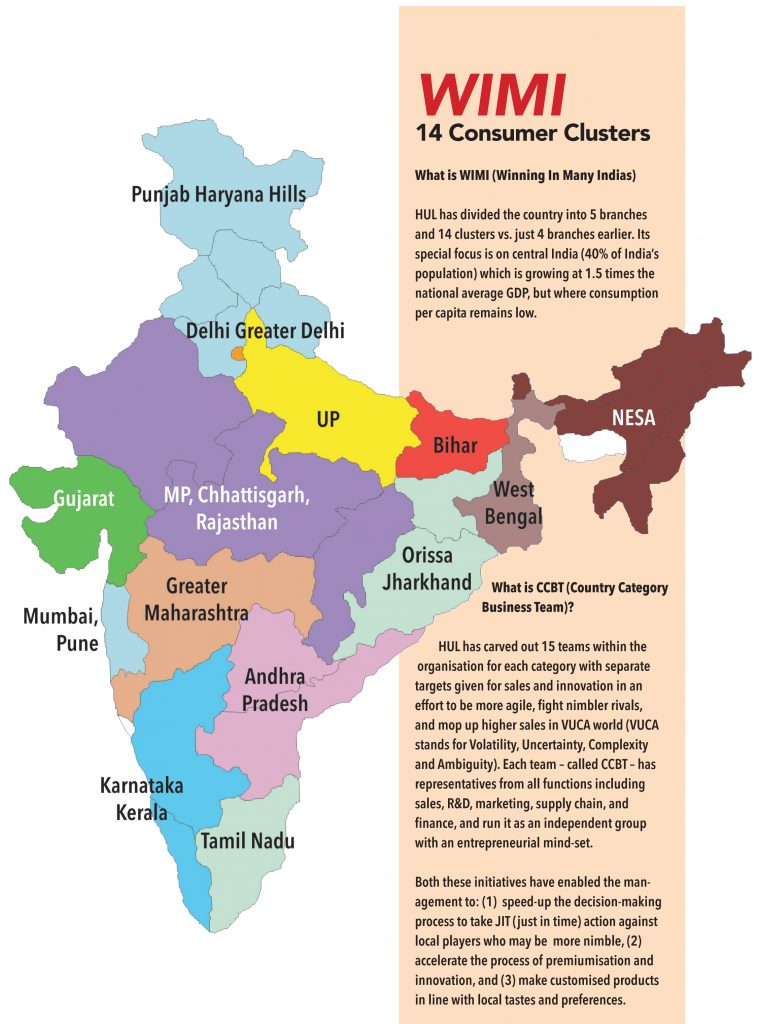

Hindustan Unilever has given enough firepower to its executives at the ‘cluster’ level to take combative action against state-specific and regional players under its initiatives – CCBT (Country Category Business Team) and WIMI (Winning in Many Indias – dividing the country into 14 clusters). Under WIMI, HUL launched detergents at different price points in Uttar Pradesh to shift consumers from local brands to Rin.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access