Quite often, civic authorities are panned for their myopic view – building infrastructure at best for today’s needs and at worst, for yesterday’s needs. Seldom have infrastructure projects been designed in India taking into account the landscape transformation and the associated needs for the next 10-20 years. The impact is visible in most tier-1 cities today – the metro networks should have been constructed at least a decade ago, and it is not surprising that authorities are finding it extremely difficult to execute them now due the rise in population and traffic over these years.

Learning from the mistakes of the civic bodies of tier-1 cities, or call it the compulsive need of today’s politics to showcase development agenda, many of the tier-2 cities that do not need metros today have already started preparing development plans for them to be carried out in the next five years. Few of them have already started execution, and some have already commissioned part of the proposed network, or are close to doing so. Happy times ahead for the citizens of these cities!

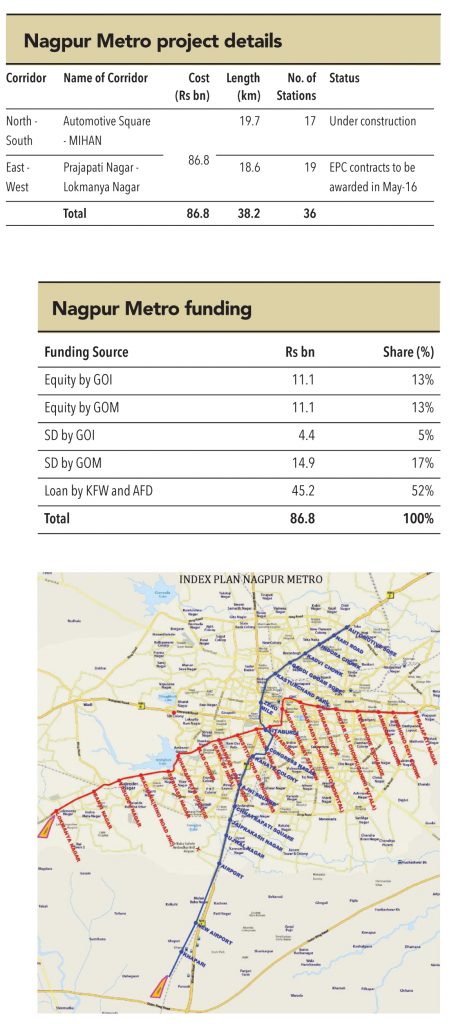

The Nagpur Metro Rail Project is envisaged to be 38.2km long with two corridors – North-South (19.6km, 17 stations) and East-West (18.5km, 19 stations). The total project cost of the 100% elevated project is estimated at almost Rs 87bn. More than 80% of the project land is already in possession. Contracts for viaduct on 12km section, from airport to Sitaburdi (intersection point of two corridors) were awarded in June and October 2015 – construction work has already begun. Contracts for 10km section on East-West corridor are expected to be awarded in May 2016.

The state government had earlier approached JICA to fund up to 40% of the project. However later, KFW of Germany and AFD of France agreed to provide loans of € 500mn and € 130mn respectively, to fund over 50% of the project cost. The Maharashtra state government intends to commission the first phase by CY18 end and the entire project by CY19.

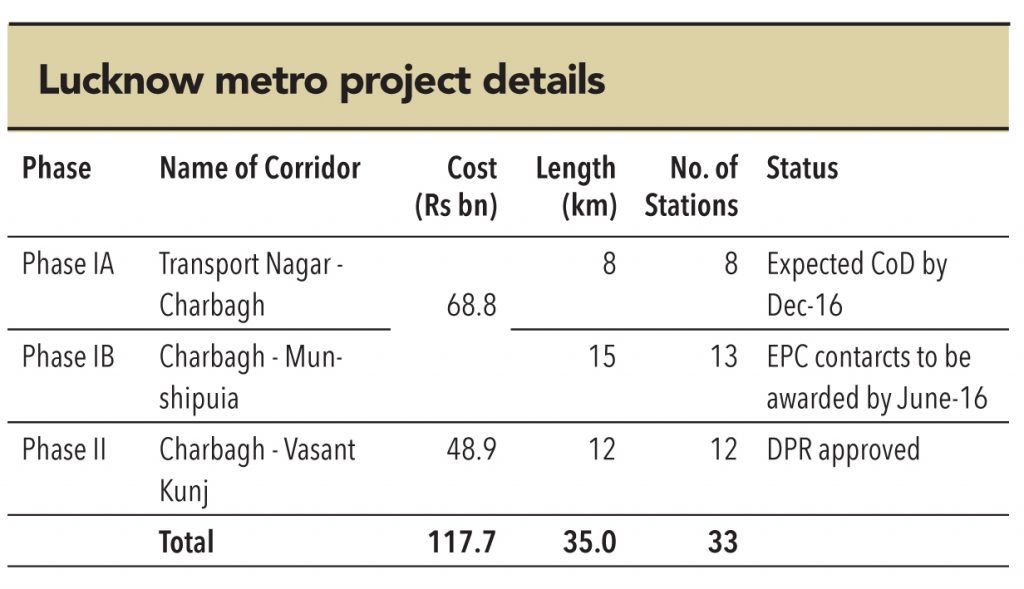

Lucknow is one of the largest and one of the most congested cities in northern India. The city desperately needs a public transport system; current roads and public buses are largely inadequate to suffice the needs of its citizens. The city has gone through a remarkable facelift over the last few years – first by the various parks built by the then ruling state government (BSP) and thereafter by the cycling lanes built by the current state government (the Samajwadi Party – whose party elections symbol, ironically, is a bicycle). An efficient and convenient metro network is what it needs to befit the rich culture and heritage of the city.

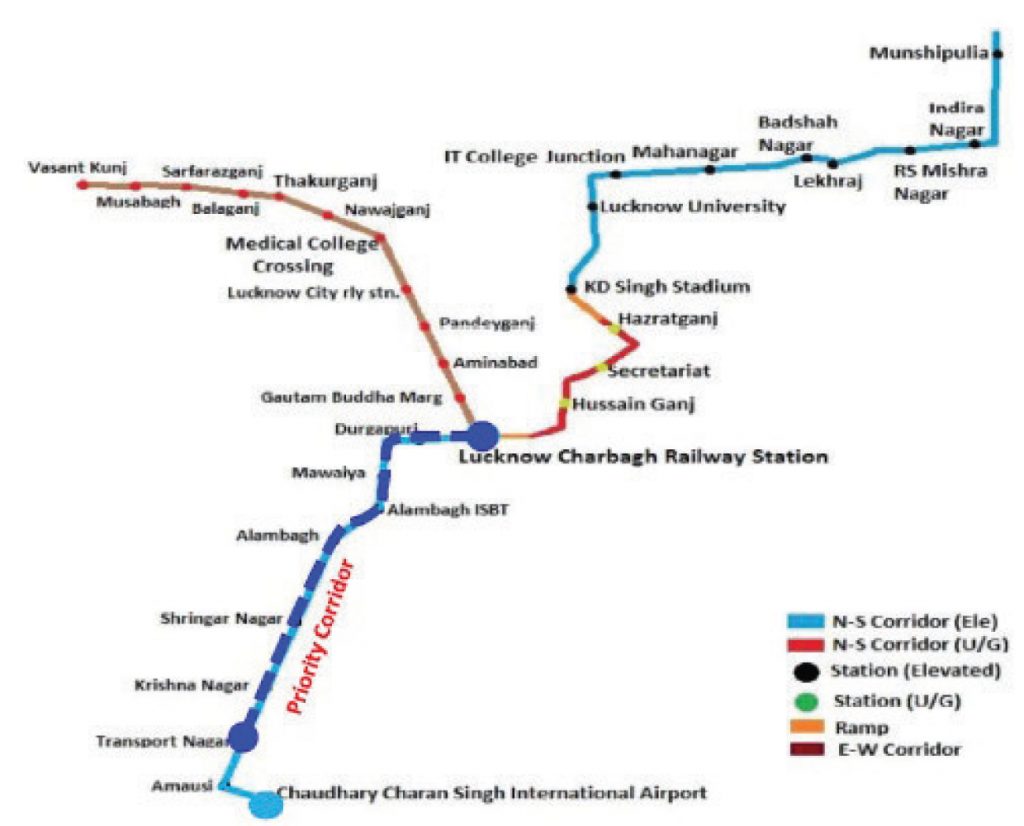

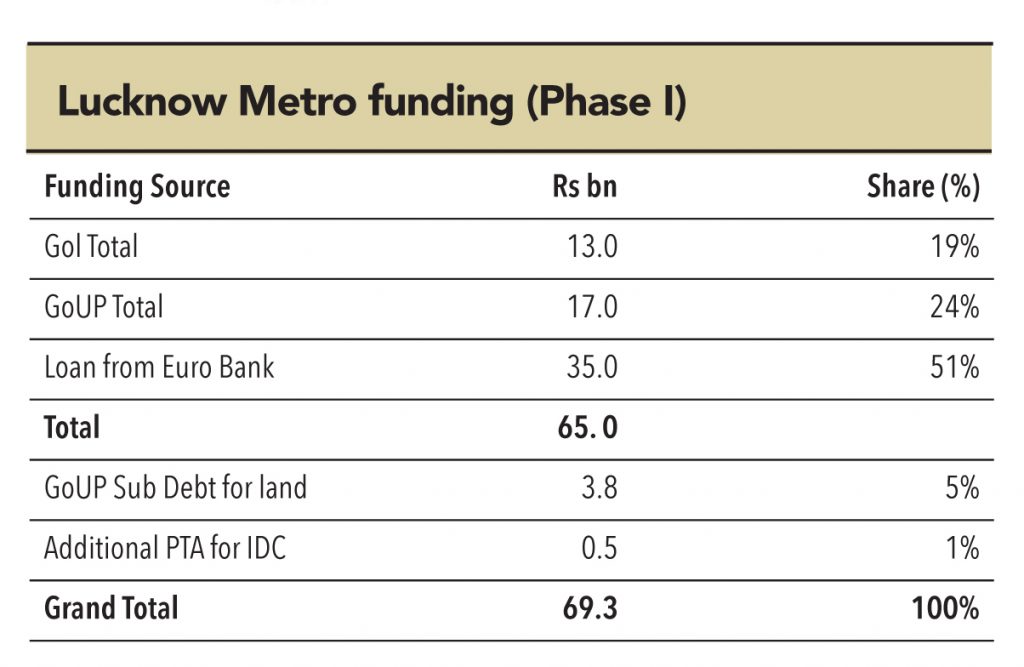

Lucknow is all set to be the first city in Uttar Pradesh to get its metro service (excluding NCR cities, which are connected via the Delhi Metro). EPC contracts for the 8km-long Phase 1A were awarded in September 2014, with a scheduled completion date of March 2017. However, in view of the upcoming state elections, the state government has preponed the commissioning date to December 2016. Work is in full swing and is expected to be complete in time. Tenders for Phase 1-B are expected to be awarded by June 2016 and execution is scheduled to start before December 2016.

The funding for phase-1 (A and B) is tied up – 52% has been arranged from Euro Bank and the remaining as equity from the Government of India and the Government of Uttar Pradesh. The state government expects healthy passenger traffic from the beginning and significant decongestion in road traffic after the metro is commissioned.

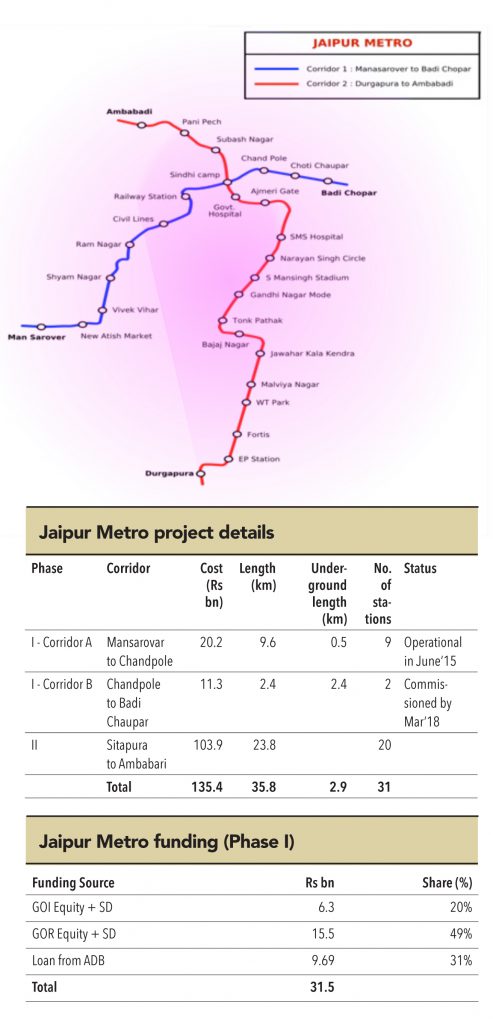

In June 2015, Jaipur became the sixth Indian city and the first tier-2 city (arguably) to join the metro bandwagon. It was a historic day for the citizens of the city as the first phase of 9.7km connecting Mansarovar to Chandpole was commissioned in record four years – with ZERO time/cost overruns. Currently, the operational network has a daily ridership of 50,772 passengers.

The Jaipur Metro project is unique in many ways – it is one of the projects where the state government offered a higher share of investment (49%) as compared to the usual 20-25% put in by most other state governments. This was made possible due to the innovative financing model of the project, where local authorities like Jaipur Development Authority, Rajasthan Housing Board, and Rajasthan State Industrial Development & Investment Corporation also contributed towards the state’s share. This also means the project required lesser funding from external sources (31% loan from ADB) – leading to a much superior FIRR (8.24%).

The land acquisition process for the Jaipur metro was very smooth and most expeditious, with the state government setting up an Empowered Settlement Committee, which worked out mutually agreed rehabilitation packages for every project affected person (PAP). Even in terms of planning, Jaipur Metro is set to become a good example of multi-model integration, as it connects the railway station, inter-state bus terminal, and Jaipur’s international airport with inter- change facilities; it is providing for bicycles, cycle rickshaws, auto-rickshaws, and bus-bays in most of its stations.

The Jaipur Metro project is likely to cost Rs 135bn and will be executed in two phases covering 35.8km with 31 stations. Of these, 12.1km is being developed in phase-1 and 23.8km will be constructed under phase-2. At present, work on phase-1B (completely underground) is in progress and is scheduled to be completed by March 2018. Construction of phase-2 will be taken up thereafter.

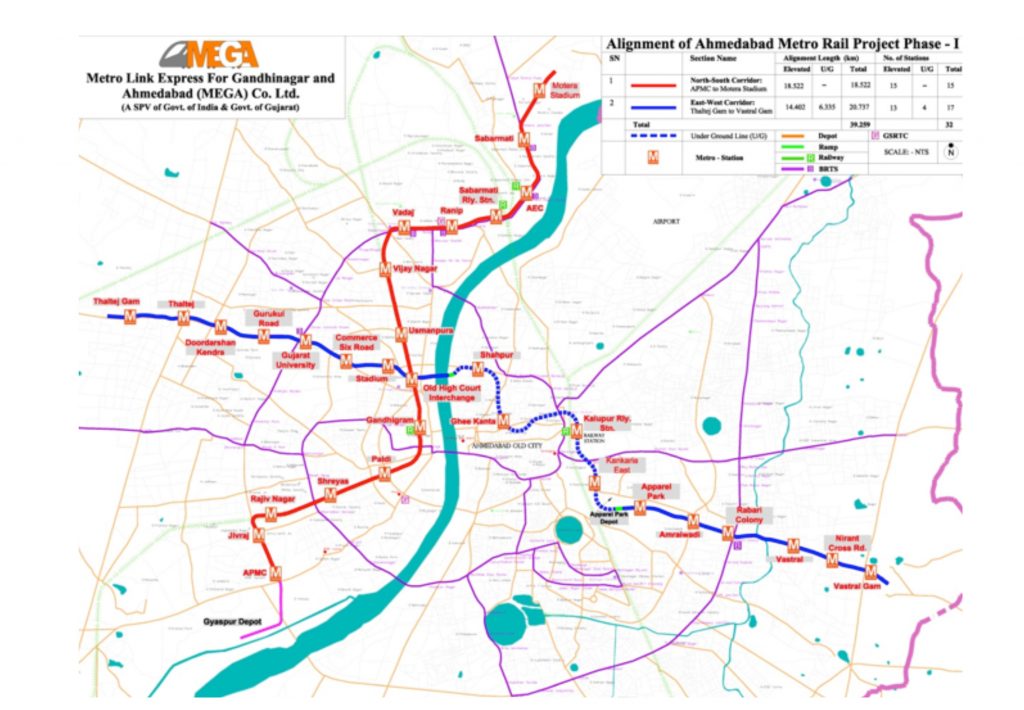

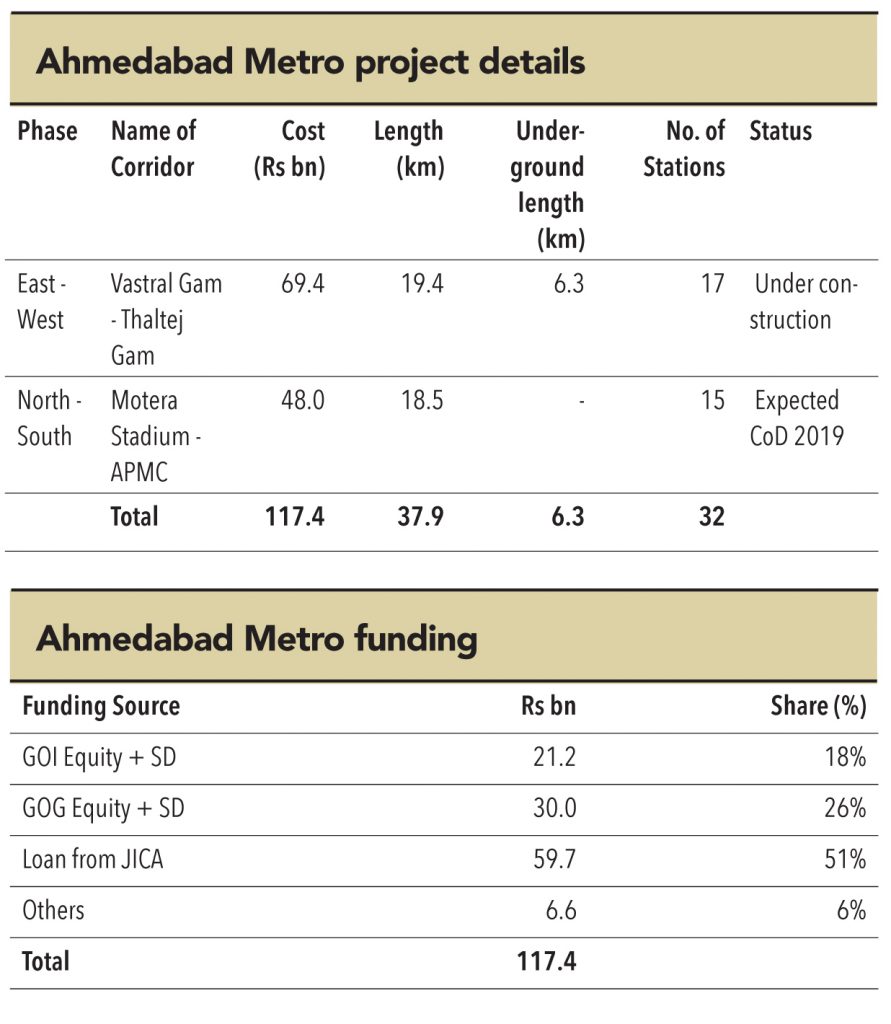

Ahmedabad doesn’t really need a metro today. It is the only city in the country that has been able to implement a BRTS (bus rapid transport system) successfully. With a population density of less than 900 people/sq. km, it is one of the relatively sparsely populated cities in India, with superior quality of roads and public infrastructure. However, it has always been the forward-thinking of the authorities in Gujarat that has made the state one of the fastest growing in the country.

The MEGA (Metro-Link Express for Gandhinagar & Ahmedabad) corridor is a 38km metro network that criss-crosses the city along four directions. The two corridors, designed along north-south and east-west direction, aim to connect the far flung areas of the city, apart from providing connectivity to the state capital – Gandhinagar. The ground breaking ceremony for the project was held in May 2015 for the construction of the Vastral-Apparel Park stretch of the east-west corridor. The construction of this stretch is expected to be complete by October 2017. The north-south corridor is expected to be complete by 2019.

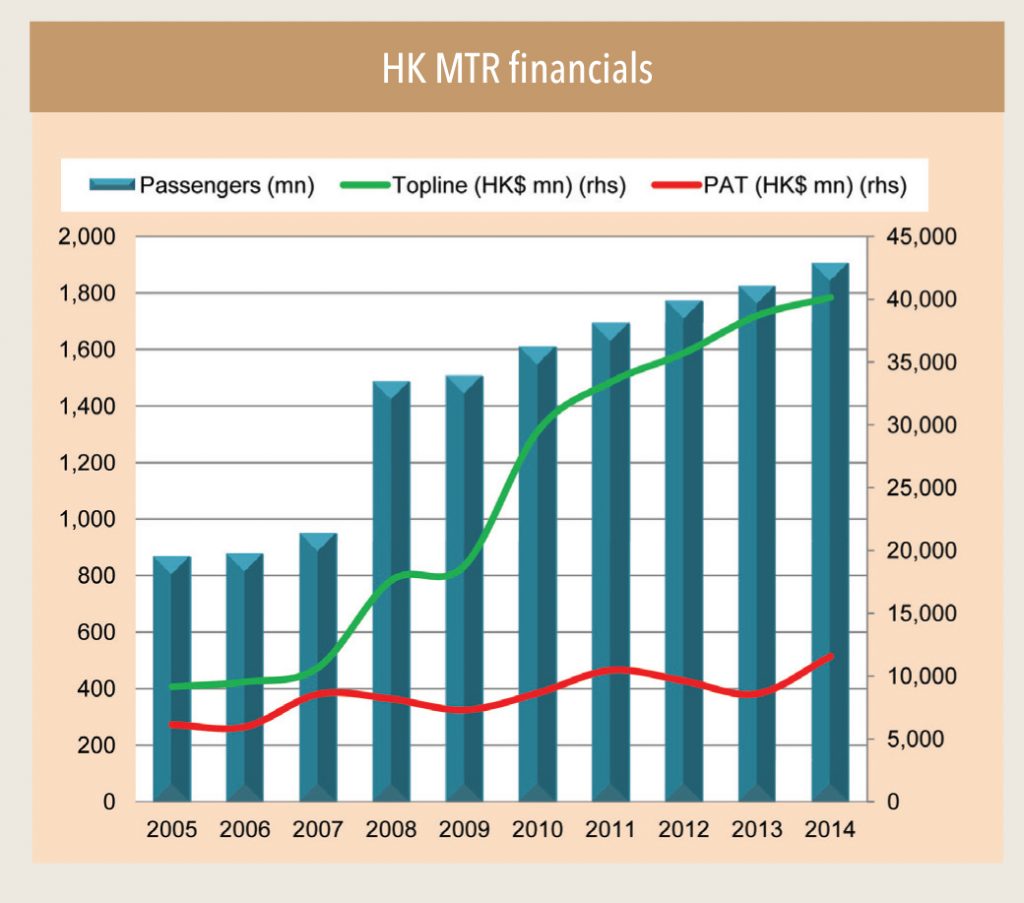

Hong Kong Metro (HKMTR) has the envious stature of being the only profitable metro system in the world. While the financials of most major metro systems are not available in the public domain, their ever-increasing debt levels to fund incremental capex clearly allude to their inadequate cashflows, and hence, profits. But how does HKMTR achieve this seemingly impossible task on a network length much smaller than most other major cities?The answer is a potent combination of highest levels of operating efficiency,high population density of the city, the ecosystem that makes it prohibitively expensive to own private vehicles, and above all, the ‘other businesses’ operated by the HKMTR. Hence, despite one of the lowest base fares in the world, the HKMTR is able to churn profits, year after year.

The HKMTR system was established as a public entity in 1974 before being privatized as the MTR Corporation in 2000, as the HK government tried to divest its ownership in public utilities to reduce expenditure and boost efficiency. However, the government remains a major shareholder (with 76% stake) of the MTR Corporation.Running for 20 hours and making 8,000 train trips per day, HKMTR boasts of a staggering 99.9% punctuality rate. Each year, it invests HK$ 5bn (US$ 645mn) in maintenance, upgrades, and renewals to the system.In fact, HKMTR has the world’s highest FBRR (fare-box recovery rate) – the percentage of income derived from ticket sales weighed against operating expenses – between 150-180% vs. less than 100% for most other metros across the world (NY Metro’s 60%).

The incredibly high FBRR can be attributed partly to the city’s densely packed population (6,500 people per sq. km. – as compared to 5,000 for London). Despite having a lesser track length than other MTRs (London 402km, New York 373km), the 218km HKMTR carries over 5mn passengers daily – the fifth highest in the world – 90% of HK residents use the MTR.

This high level of ridership exists partly due to the ecosystem. There are no suburbs in HK, from where people can commute by car. That, along with other regulations, has kept car ownership low – only six of every 100 vehicles in HK are for personal use, as compared to 70 in the US. HK freeways are also much narrower and streets are much harder to drive through. Parking is prohibitively expensive.

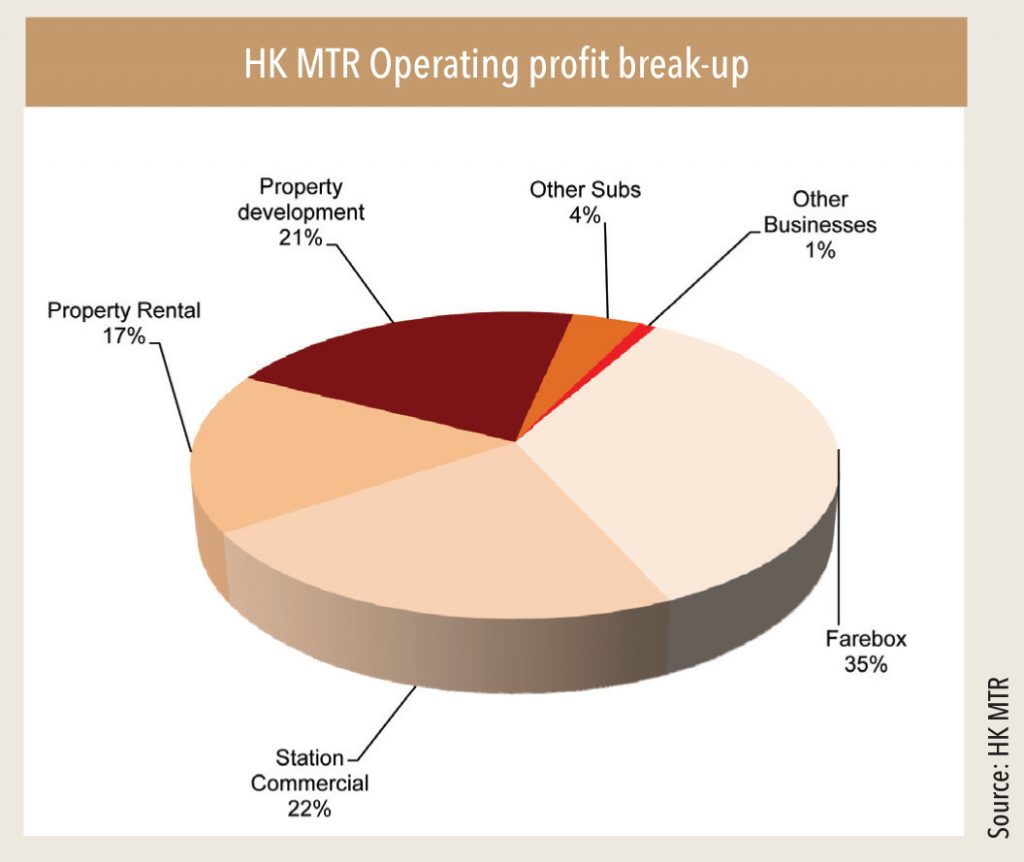

But the company’s real profits (60% of operating profits) are derived from its ‘other businesses’ – primarily, property development. HKMTR owns and manages around 50 major properties across HK, including two of the city’s tallest skyscrapers and 13 malls. The HK government provides land to HKMTR at zero cost, allowing it to develop the areas above and around its stations. Almost each station is packed with retail outlets, which either pay rentals or have profit-sharing agreements with HKMTR. “Sometimes critics say it’s a property development firm doing a side business of rail,” said Tim Hau, a professor at University of Hong Kong’s School of Economics and Finance. Thus, the HKMTR essentially functions like a vertically integrated business through a “rail plus property” model, controlling both the means of transit and the places passengers visit upon departure. Over the last few years, it has spread its wings beyond HK and now operates the London Overground, two lines of the Beijing Metro, parts of Shenzhen and Hangzhou MTR in China, Melbourne Metro, and the Stockholm Metro.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access