India saw one of its best periods, in terms of economy, in the 1960s – when two major revolutions swept across the country. The Green Revolution – which led to significant enhancement in agriculture productivity; and the White Revolution – which made dairy farming the country’s largest self-sustaining industry. More than half a century later, we are about to embark upon a new revolution that will transform India’s agricultural landscape and provide a major disaster-control mechanism. The plan to connect India’s rivers – or the National River Linking Project – will not only provide mammoth irrigation benefits to farmers, but also help the government to avoid huge economic losses arising from recurring floods and droughts. The current government has taken the project in right earnest, and is leaving no stones unturned to ‘revive’ it. This mammoth Rs 11trillion project, could well be the next big revolution in the history of the country – The Blue Revolution.

The inter-linking of the river project (or the National River Linking Project, NRLP, as it is called) is perhaps the most-hyped infrastructure project in India so far, and always surrounded by controversies. It has also made little or no progress since its inception three decades ago. The history of the ‘concept’ dates back to the 19th century, when Sir Arthur Cotton, working as an engineer with the Madras Presidency under the British rule, proposed interlinking rivers to promote inland navigation and water transport – but his plans were rejected in favour of railways. After that, as has been the case with any mega project in this country, multiple committees were formed to ‘study’ the project, its benefits, and its impact. Eventually, in August 1980, the Ministry of Irrigation prepared a National Perspective Plan (NPP) for Water Resource Development. As it stands today, the 1980 NPP provides the basic framework for the Interlinking of Rivers project – with few modifications/enhancements made since it was proposed.

India – a unique topography

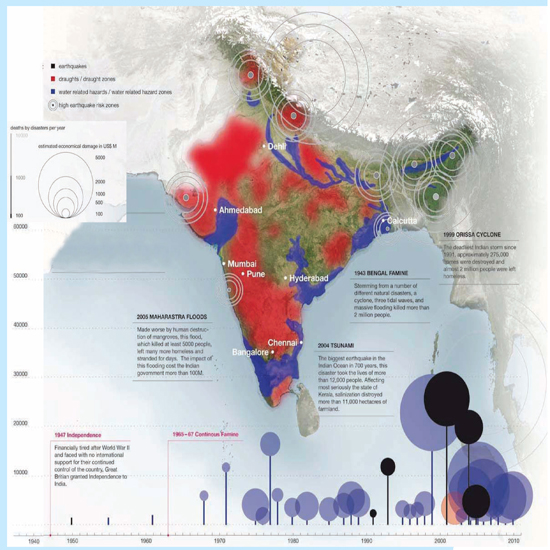

India is endowed with enormous water-reservoir potential. The average annual water flow in the country is estimated to be 1,869 bn-m3 (BCM). But, there are wide variations in availability of fresh water over the geographical space and time period in the country. Although India holds 2.4% of the world’s land area and 4% renewable water resources, its share of the world population stands at a much higher 17.5%. Also, the rainfall pattern in India is highly skewed, with most of the rain occurring in the southwest monsoon months, while the rest of the year remains relatively dry. Prolonged dry spells exacerbate this uncertainty in rainfall. As a result, parts of Haryana, Maharashtra, AP, Rajasthan, Gujarat, MP, Karnataka, and TN tend to face rainfall deficits, resulting in droughts.

In contrast, excess rainfall results in regular floods in the Brahmaputra and Ganga river basins, which affect Assam, Bihar, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh. According to an estimate by the WHO, economic losses due to floods and droughts in 1990-2001 in India were at US$ 4.6bn. With an increasing population base, the per-capita availability of water in India is rapidly declining. From 5.2k-m3 in 1950, it came down to 1.82k-m3 in 2001 and declined to 1.55k-m3 in 2011. It is expected to drop to as low as 1.34k-m3 in 2025!

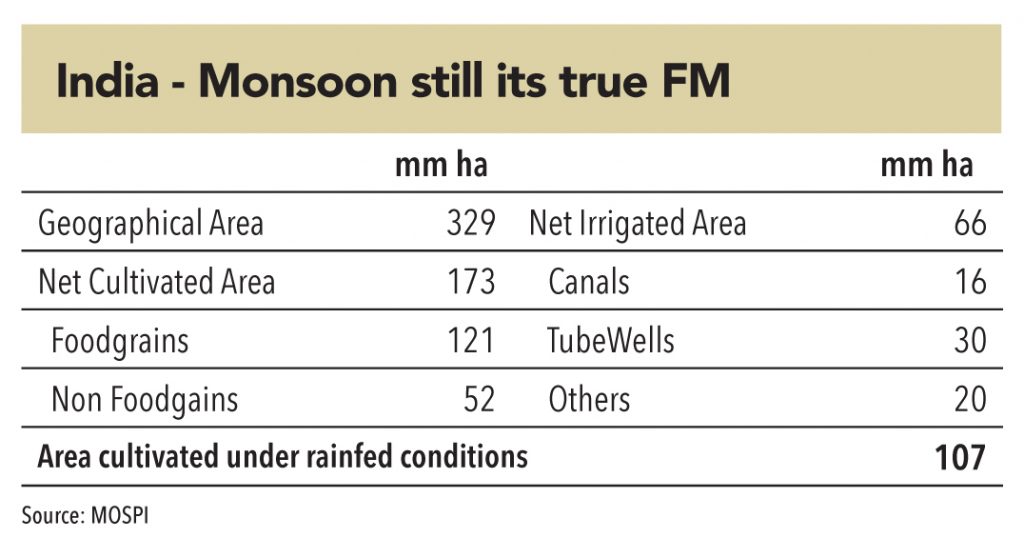

Agriculture still remains the primary source of livelihood in this country. It contributes 15% of GDP and employs over 40% of the workforce. However, irrigation in India is still highly dependent on rains – even after 70 years of independence and scores of dams/canals that have been built. The current net cultivated area in India is 173mn ha. – foodgrains comprising a mammoth 121mn ha. However, only 66mn ha. of that area, is irrigate by canals, tube wells, wells and other means. A humongous 107mn ha. (almost 2/3rd) of the net cultivated area, is still dependent on the erratic monsoons. Little wonder then, that the monsoon is called India’s true finance minister’.

For such a unique topography, with an erratic source of irrigation – the need for a large institutional mechanism, which maintains parity in water distribution, cannot be over emphasized. The linking of rivers project is something that India needed in the previous decade – the question is, will it be executed at least over the next decade?

In the 19th century, Sir Arthur Cotton, a royal engineer working with Madras Presidency, proposed a plan to interlink major Indian rivers to promote inland navigation and transport. However, the plan was shelved in favour of railways.

In 1972, Dr K.L. Rao, an engineer and former irrigation minister, proposed a “National Water Grid”. His plan envisaged a Ganga-Cauvery link that would divert surplus water (from Brahmaputra and Ganga basins) to deficit areas (central and south India). By that time, several inter-basin transfer projects had already been successfully implemented in India. However, even Rao’s plan too did not see the light of day as it was perceived to ‘lack’ any flood-control benefits.

In 1977, an Indian Airlines Pilot, Captain Dinshaw Dastur, proposed constructing two canal systems – the Himalayan Canal (at the foot of Himalayan slopes, running form the Ravi to the Brahmaputra), and the Garland Canal (in the central and southern parts of the country).

In 1980, the Ministry of Water Resources came out with a report “National Perspectives Plan (NPP) for Water Resources Development” – which drew its design from Captain Dastur’s proposal. The report split the water development project into two parts – the Himalayan and Peninsular components.

In 1982, a committee of nominated experts was setup, through National Water Development Agency (NWDA) to complete detailed studies, surveys, and investigations about reservoirs, canals, and all aspects of the feasibility of inter-linking peninsular rivers and related water-resource management. Over the next 35 years, from 1982 to 2017, NWDA conducted multiple studies ad produced many reports.

Most central governments have caved in to opposition from various camps – from ecological and environmental issues, to rehabilitation of people, and lack of national/international consensus. In 1999, the NDA government, under the leadership of the then PM, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, tried to revive the project – it formed a national-level committee to build consensus among various states. However, over the subsequent decade, under the UPA rule, the project was put on the back burner.

In 1977, an Indian Airlines Pilot, Captain Dinshaw Dastur, proposed constructing two canal systems – the Himalayan Canal and the Garland Canal – which form the underlying design for the current NRLP

In 2014, as the NDA came back to power, it revived the project and started building consensus. Over the last two years, multiple clearances have come through and many obstacles have been surmounted for some of the project’s key components. The latest fillip came from the recent cabinet reshuffle in which the Surface Transport minister, Mr Nitin Gadkari, took over the Ministry of Water Resources. Mr Gadkari is not only seen to be aggressive in terms of execution, he has an established penchant for mega projects. Soon after taking charge, he set the ball in motion for the interlinking project and is looking to start work as early as December 2017.

India has a unique problem – it is hit by droughts and floods within the same year, year after year. With rainfall patterns highly skewed, and a non-existent water transfer mechanism – from water surplus to water deficit regions, the problem has only aggravated over the last few decades despite huge investments in dams and canals across the country.

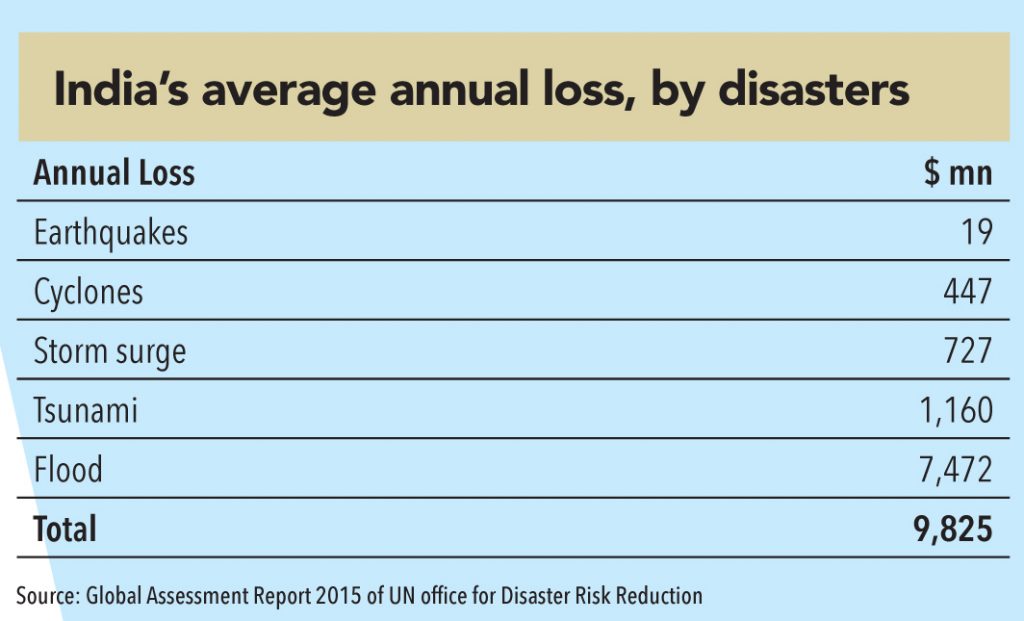

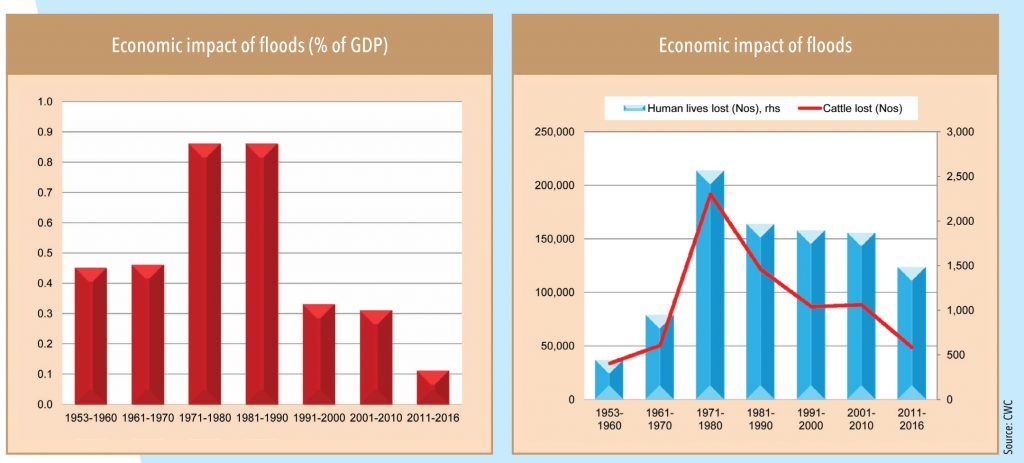

The problems associated with floods are particularly alarming. A United Nations report on ‘global assessment of disaster risk’ estimates that India’s annual average economic losses due to floods are US$ 7.5bn, and total economic losses due to all forms of disasters are US$ 10bn. This is a huge cost for a nation in which 24% of the population still lives below the poverty line (officially). In a similar analysis, the Central Water Commission (CWC) estimated that economic losses due to floods in India were 0.11% of the GDP in 2011-16 – though these were lower than 0.86% of GDP over 1970-1990. At 0.11% of GDP, the losses amount to US$ 2.5bn, 1,500 human lives, and 48,000 cattle.

On the other hand, recurring droughts in water-deficit regions (Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Karnataka) have led to huge economic losses and human lives. An Assocham study estimates that two years of successive droughts in 2014 and 2015 led to economic losses of US$ 10bn in 10 states in India. Moreover, ‘the impact of drought is likely to remain for at least six months, after the drought, because one needs resources and time to revive the activities on ground even if monsoon is predicted to be normal the next year’, the report said.

The Indian government has spend over US$ 30bn over the last 30 years on disaster recovery (as per the CeEDMM, IITR). While few of the events were unprecedented (and unavoidable) – like the 1999 Odisha cyclone and the 2004 Tsunami – a large part of this mammoth economic loss is attributable to recurring (and avoidable) floods and droughts in the country.

The Centre of Excellence in Disaster Mitigation and Management (CoEDMM) is the first center of Disaster Mitigation and Management in India. It was established in 2006 with the aim of conducting the educational program, cutting edge research and training on disasters, vulnerability and their mitigation. Creation of a National Database for rapid dissemination of information and knowledge is also an objective. The centre has faculty with domain expertise in earthquake, landslide, cyclones, floods, tsunami cyber crime, avalanche, fire, industrial disaster, CBRN (chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear) and geomatic technology. Various research and consultancy projects are being carried out through sponsored funding from Govt. of India and other national and international funding agencies.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access