Observations from CAG clearly highlight the chinks in India’s armour. Its defence forces have faced a shortage of personnel and critical equipment because acquisition and modernisation plans remain stuck in a mesh of bureaucracy. Out-dated equipment, technologically backward, low reliability, and perennially in short supply – these are just some of the problems with India’s defence equipment. Delayed modernisation has ensured that defence capabilities are way behind countries such as China. India now spends 1.1% of its GDP on defence (capital expenditure ex-land and construction), which is higher than the US (0.8%) and largely in line with that of UK (1.4%). While India’s capital defence spending has increased (vs. US and UK), only a small part of it goes towards new equipment. In addition, almost 60% of the annual capital budget is towards imports, mainly because India’s defence PSUs lack the expertise to manufacture complex systems and private sector participation is nascent. In order to correct this anomaly, the current government has taken steps towards changes to procurement procedures – by introducing new category IDDM, revision of the defence products list, issuing industrial licenses to the private sector, and relaxing FDI norms. Ground View undertook case studies across three segments of the defence industry – defence PSU (Hindustan Aeronautics), private sector (Tata Power‘s four-decade-old Strategic Electronics Division), and an MNC (Safran).

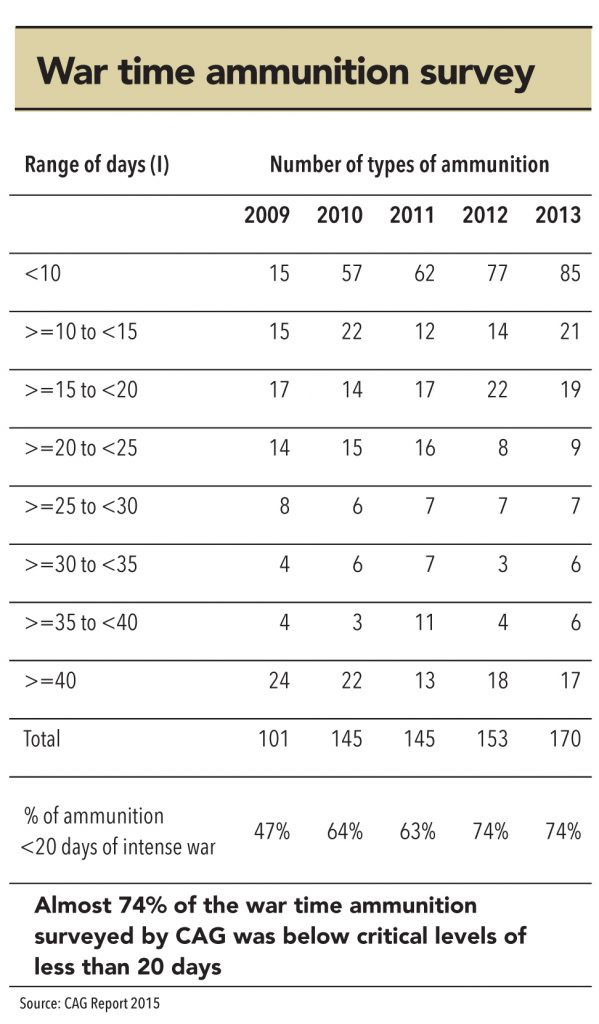

In December 2015, Comptroller & Auditor General (CAG) observed that Indian Army’s availability of authorised stock against War Wastage Reserve (WWR, which measures war preparedness) is low. Thus, against a WWR of 40 intense war (I) days, in 50% of the total types of ammunition, the availability was ‘critical’ – i.e., less than 10 (I) days. Inability of the Ordnance Factory Board (OFB) to meet the army’s demand was a major cause for this shortage. Delayed modernisation has ensured defence capabilities are way behind countries such as China.

An independent defence consultant highlighted that India’s annual capital defence spending has averaged US$ 11bn per annum over the past five years. However, only about 8% of this capex goes towards ordering new equipment; the rest is payments for equipment that was bought earlier.

The reasons for the under investment, he said, are well documented – India shares a border with two hostile neighbours – Pakistan and China. Also, its defence forces face serious shortages of critical equipment – not just fancy high-tech equipment, even basic war-time necessities.

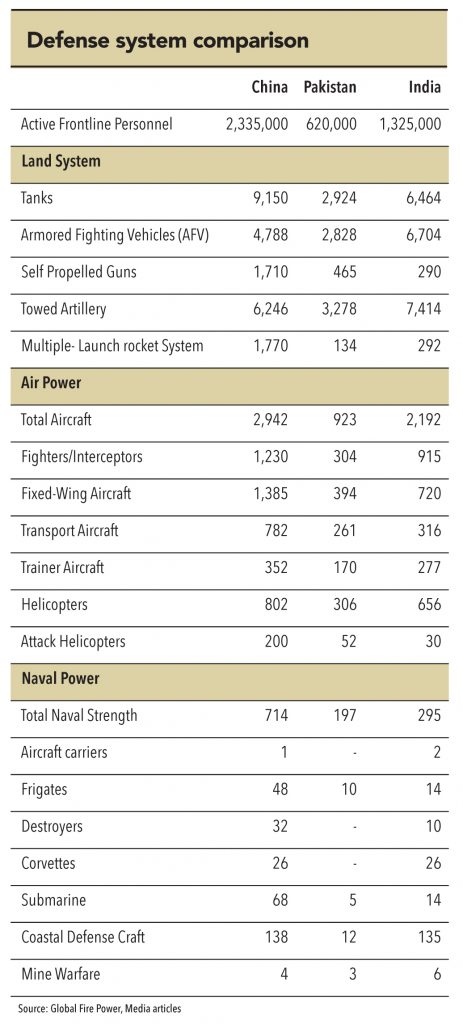

How does India stack up against its two closest neighbours?

India’s defence strength exceeds Pakistan’s, but it is grossly inadequate compared to China’s. More ominously, India’s equipment is out-dated; hence, even if its numbers seem large, its equipment reliability in active combat is low.

It is a generally agreed that India’s defence expenditure needs to see a quantum jump from current levels

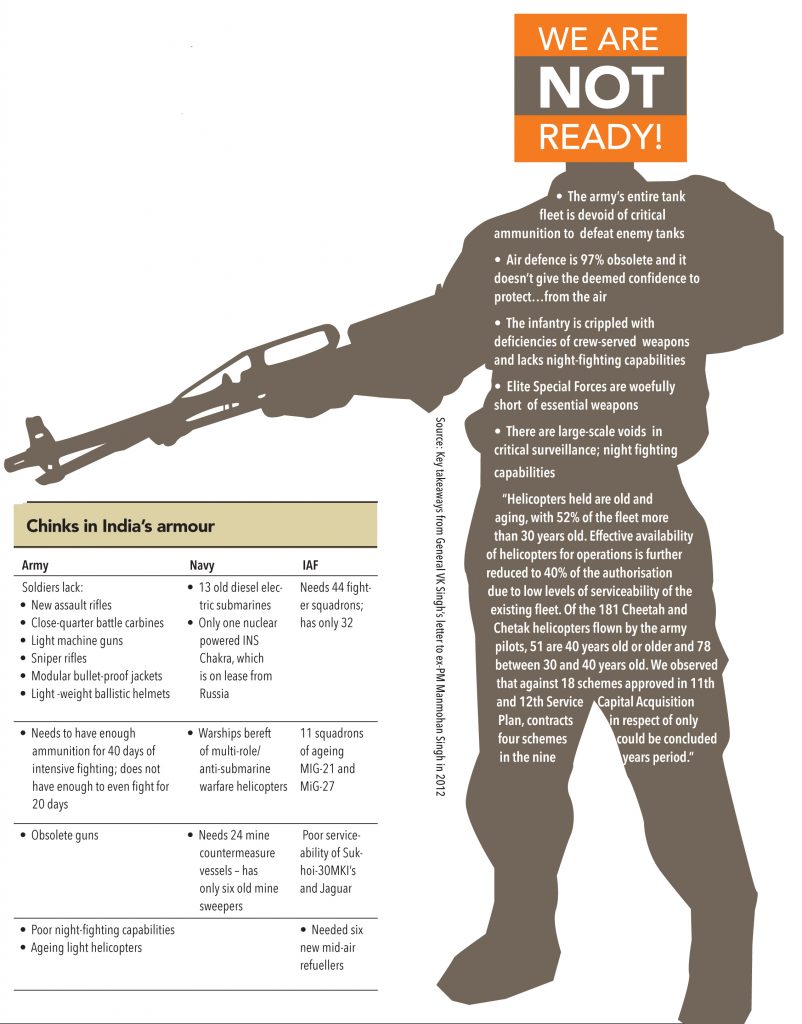

Severe shortage of critical equipment

Indian armed forces face a shortage of equipment across the board. Right from ammunition for rifles, bulletproof jackets,howitzer guns, submarines, to fighter jets. For instance, the Indian Air force operates only 32 squadrons of fighter aircrafts against the mandated 44; over the next five years, it will retire about seven more squadrons of ageing planes.

Defence forces have faced a shortage of personnel and critical equipment because acquisition and modernisation plans remain stuck in a mesh of bureaucracy

CAG observed that availability of authorised stock against War Wastage Reserve (WWR, which measures war preparedness) has been low. Thus, against WWR of 40 intense war days, in 50% of the total types of ammunition, availability was ‘critical’ – i.e., less than 10 (I) days. Inability of the Ordnance Factory Board (OFB) to meet the army’s demand was a major cause for this ammunition shortage. Delayed modernisation has ensured defence capabilities are way behind countries such as China.

Source: CAG comments in December 2015

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access