Until 2015, the Indian cable and broadcasting industry was relatively untouched by the digital revolution. But over the last few years, various OTT platforms exploded on the Indian scene and global on-demand service providers such as Netflix and Amazon Prime also entered India. With over 40 OTT platforms, the audience in India is now spoilt for choice. According to a Media Partner Asia (MPA) report, in 2014, India had 12mn active OTT video subscribers – expected to rise to 105mn by 2020.

A media executive from a leading broadcasting company says, “Currently, OTT services are targeted at premium customers, who form a miniscule proportion of overall TV viewership – at least for now. If only these customers subscribe to OTT services, it is not going to break the linear TV viewership business model.”

How does Netflix grapple with India’s thirst for local content?

Not only does India have Bollywood, it also boasts of many more regional cinema industries – Telugu, Tamil, Bengali – each with its own massive fan following. Every year, India churns out more than 1,500 movies, the largest in the world. In order to have mass subscription, Netflix would need to invest heavily in local movie content, which could prove a daunting task for any new entrant. In India, digital rights of old movies either lie with some broadcaster or with an existing OTT player.

“A big drawback for Netflix is its inability to channel local content, the way rivals such as Hotstar, Spuul, and Eros Now have managed to do, albeit in a fragmented way,” says the strategy head of a niche content production company. Publishers face problems in providing a rich portfolio of content across India’s myriad languages.

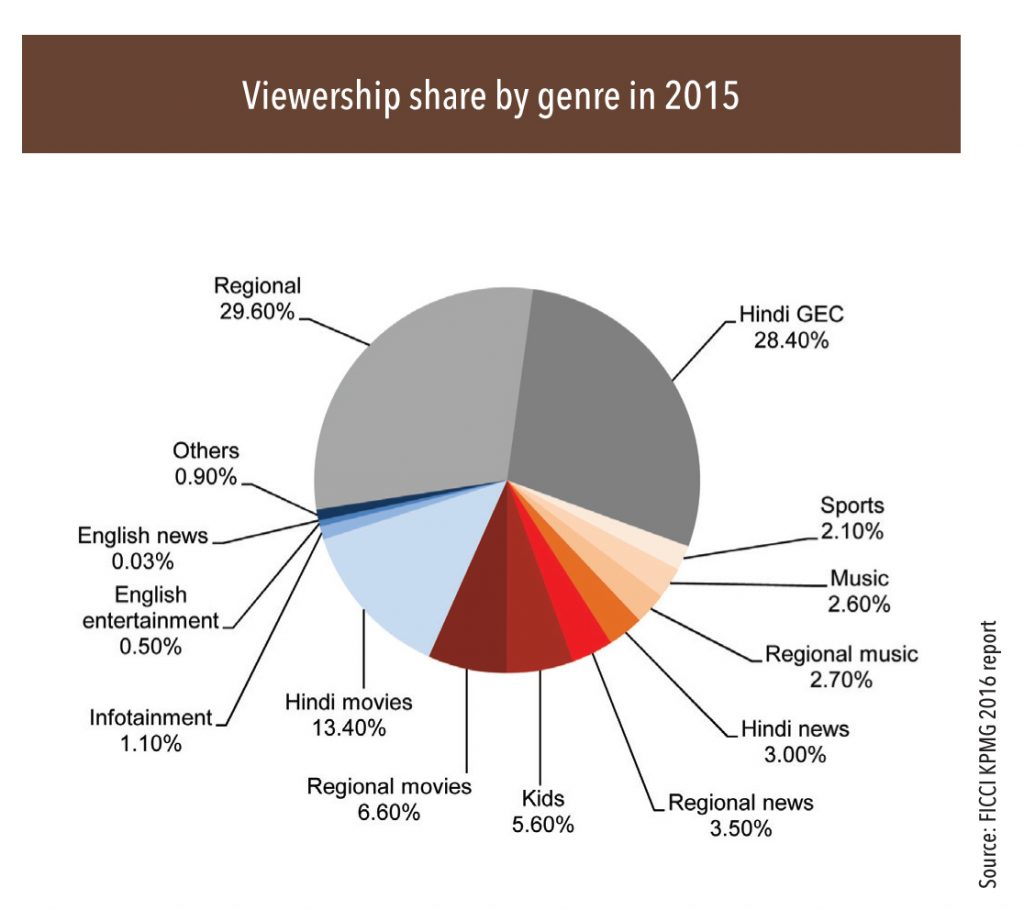

The country’s diversity also adds to the multiplicity of genres and volume of content that a provider would need to cover the entire spectrum of languages across the country. While there is moderate demand for English content in India, the broader market consumes local, regional, and Hindi content at significantly lower pay-tv ARPUs.

An inferior offering in India

Another problem for a player like Netflix is that a large part of its content is not licensed for India, which makes its India offering sub optimal. For e.g., the TV series House of Cards is not available on Netflix as it sold its rights to Zee for India. A senior executive for a leading English broadcaster has a balanced take on this. He says, “A lot of the Netflix content has not been syndicated to channels in India, so that is one advantage it has. It is too early to say what impact it will have on broadcasters, because internationally too, Netflix has not really substituted TV – they co-exist”.

According to unogs.com, which keeps a record of the number of TV shows and movies that are available on Netflix in various countries, Netflix India had only 563 movies and 263 TV shows in January 2016, while Netflix in the US offered 4,567 movies and 1,114 TV shows. Six months later, Netflix offered 916 movies and 368 TV shows, while in the US, Netflix offered 4,042 movies and 1,138 TV shows – while Netflix’s India library is growing slowly, it’s growing nevertheless.

English viewership share is too small, mass market rules

In India, the TV viewership share of English content is much less compared with Hindi and regional languages, which command a lion’s share. “I don’t see any significant impact on broadcasters or other digital players in the near term, as only 5-7% of TV-viewing audiences watch English content. Moreover, the broadband infrastructure in the country is still in nascent stages and it will take 3-5 years to build a number for critical mass,” says the business head of a leading DTH player in India.

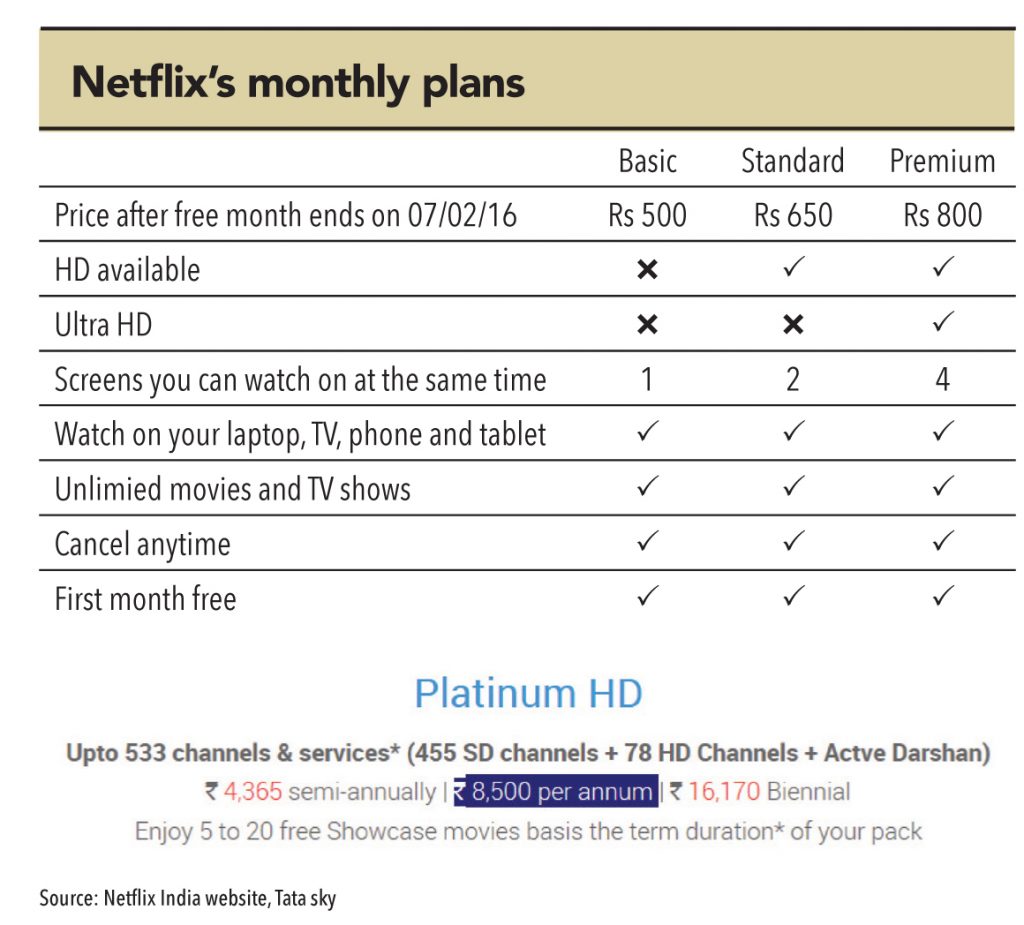

Netflix enjoys tremendous cost advantage in US and Europe where its Internet TV offering is much cheaper than traditional TV services (cable/satellite). Unfortunately, this is not the case in India. Also, India has limited number of residential broadband connections, small data limits, lack of connected media devices, and tough censorship laws. Cost consciousness is extremely high among Indian consumers, and Netflix, with its current pricing model, makes a weak case. In a country where a ‘platinum’ cable subscription usually offers 300+ channels and is available for Rs 500 a month, Netflix’s paid offering of Rs 500-800 per month is a tough sell for mass subscription. In the words of Eros International Group CEO Jyoti Deshpande, “In our experience of the partnership we had with HBO to launch premium digital ad-free channels on DTH and cable, even the Rs 200 pricing for two channels meant a ceiling of 200,000 subscribers, beyond which there was no appeal. The premium pricing that Netflix is aiming for, alienates the core category driving consumption, that is, the middle class in a mass-volume market like India.”

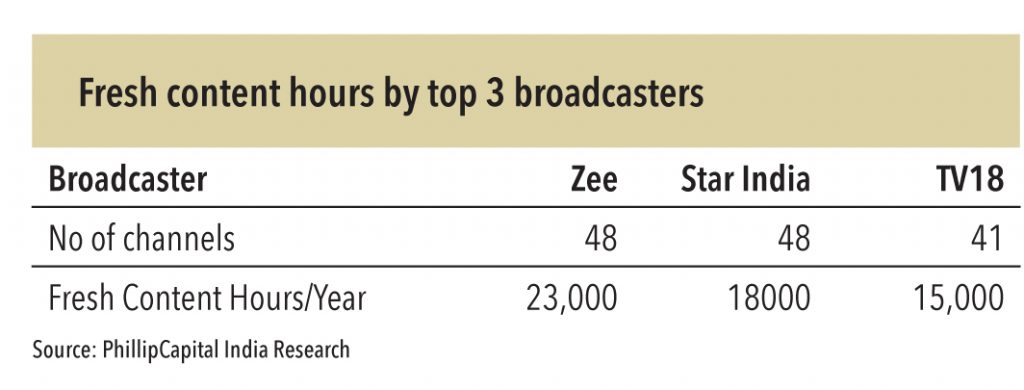

In India, it looks like Netflix’s competitors have picked up strategies directly from its playbook, in fact leaving it behind. The business model of Indian broadcasting companies is very different from ones in developed countries – unlike their western counterparts, Indian broadcasters either own the Intellectual Property (IP) of the content that they beam out, or they commission content from a third party. All major broadcasters in India – Zee, Sun, Star, TV18 – have a wide array of channels spanning languages and genres, and have been operating in India for at least over a decade.

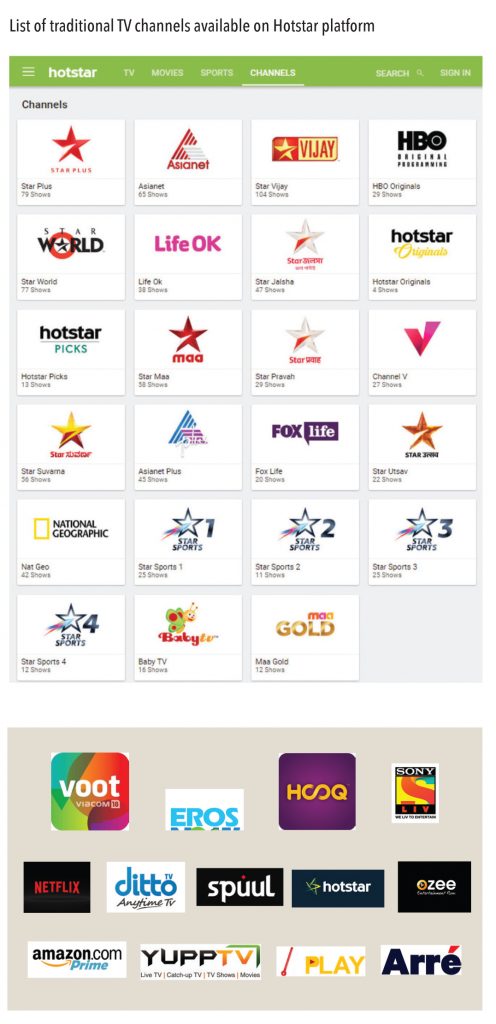

During this time, they have built a repertoire of content (daily soaps, movies), which a standalone OTT player would find difficult to replicate. Almost all broadcasters have already launched their own OTT platforms (Zee – Dittotv, Star – Hotstar, Sony – Sonyliv, TV18 – Voot) to target customers who primarily want to watch catch-up TV over a mobile platform. As broadcasters have already incurred content cost, the OTT platform merely creates another avenue for monetisation of their content – precisely the reason why broadcasters can afford to provide the content for free (i.e., without charging any subscription revenue) and still sustain the profitability of the existing business.

Broadcasters generally incur an initial start-up cost – usually the technology cost (varies from Rs 2-3 bn) and other operating cost (content) – which is easily manageable considering the financial might of established broadcasters. This is also why they can afford to provide OTT services for free, or at a nominal price.

Soon after Netflix arrived last year, Hotstar (owned by 21st Century Fox through Star India) made a deal with HBO that gave it access to most of the latter’s content, minutes after it aired in the USA. Adding to its exclusive deals, in January 2017, Hotstar tied up with Disney India to bring the latter’s film and TV slate onto its service.

Star also holds the rights to some of the biggest sporting leagues and tournaments, be it The Premier League, Bundesliga, or Wimbledon. “No other OTT platform in the world delivers this mix of entertainment and sports,” claims Hotstar’s CEO Ajit Mohan, pointing out that the platform also holds exclusive digital rights for some properties, especially cricket’s popular Indian Premier League. The IPL has become a hot property – its 10-year rights (currently held by Sony Entertainment Television) are up for renewal in 2017. Hotstar claims that in major Indian cities, more people watched this year’s IPL season on its service than on TV.

TV broadcasters expect revenues from digital platforms to grow at 10-15% in a few years, chiefly due to mobile advertising. Punit Goenka, MD, Zee Enterprises exhorts, “At an incredible price of Rs 20, we see dittoTV becoming a necessity and everyone’s default app on their mobile phones, allowing them to access TV just about anytime and anywhere. We see it serving as your first and only screen, as your second screen, or just your TV on the go!” To drive the subscriber numbers and increase the number of eyeballs, broadcasting companies are collaborating with telecom companies, who are bundling apps into the data packs or selling these to consumers – a strategy to spur data volume. Over-the-top (OTT) platforms in India are in their infancy and are currently dealing with more fundamental issues. As Uday Sodhi, Business Head, Sony Liv explains, “OTT platforms are currently focusing on increasing content consumption by sorting out peripheral infrastructure related to payment gateways, bandwidth, and video streaming.”

The business models of current OTT providers are yet to stabilise

Buoyed by the success of on-demand streaming services in the developed world, India saw a slew of launches in the OTT space. While industry experts believe that no player has found a ‘magic formula’ for monetising free OTT services, there is hope – India has a bright future for online video and audio services driven by the growth of connected devices, a large internet-enabled mobile user base, increasing internet penetration, and growing consumer appetite for on-demand and live/linear content services.

“The greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence; it is to act with yesterday’s logic.”

— Peter Drucker

Standalone OTT apps business model to revolve around ad based revenue model in the short term “India’s online video space will predominantly be an AVoD market,” claims a leading executive of an OTT player. Advertising video on demand (AVoD – free content with compulsory advertisements) services are supported by advertising, within or around online video streams, or on a website or app. Online video advertising will be driven by increased penetration of high-speed broadband and smartphones, and a greater volume of exclusive content leading to differentiated services that can command premium ad rates and sponsorships. As per a FICCI KPMG report 2016, India will improve its fixed broadband subscriber numbers to 28.3mn by 2021 from 16.6mn in 2015, and wireless broadband subscribers to 622mn from 120mn.

Although the subscription market is very small, it will pick up once data prices fall and payment gateways evolve. In the next 8-12 months, developments such as penetration of 4G services, rationalisation of data prices, and greater use of alternative payment models will help the freemium (mostly internet business model in which basic services are free while more advanced features are paid), SVoD (subscription video on demand, usually unlimited at a flat monthly rate), and TVoD (usually pay per view) business models to emerge. Digital video advertising is a US$ 1bn opportunity over the next five years. AVoD services are projected to see a CAGR of 38% between 2016 and 2021.

ALT Digital Media to try out the SVOD model – Will it succeed?

ALT Digital Media, the OTT video streaming firm of television and film production company Balaji Telefilms, eyeing an October launch, plans to produce more than 200 hours of exclusive original Indian content in a year. Currently, ALT Digital is firming up distribution partnerships with mobile phone manufacturers, telecom firms, and internet service providers. The company will follow a SVoD business model as it intends to move away from interruptive advertising to provide a value-for-money immersive viewer experience. However, it will work with select brands to integrate them seamlessly into its shows.

The big question is – how do you develop a business model in which viewers are willing to pay the content owner to view content on a second screen? A single definitive business model in OTT is missing in India. While Netflix is considered a global giant in this space, it is not sure if its model will be a game changer in India. Currently, most of the digital platform operators and standalone content providers are still experimenting with the ‘freemium’ business model and provide most services free, because of which they rely heavily on advertising revenue. Given that the subscription based business model is yet to pick-up any traction, most of the standalone OTT companies will be in investment mode for a long time, as financial data suggests that advertising income is not sufficient to cover the cost of content investment (let alone marketing). New and standalone OTT players would find it difficult to survive this experimentation phase, and industry experts believe that it be at least 3-5 years before a definite business model emerges.

Sneak peak in to Hotstar financials reveals worrying trends

Preliminary analysis of Novi Digital Entertainment Pvt Ltd (holding company of Hotsar) indicates that its revenue increased by an impressive 250% in FY16 but its operating losses widened to Rs 3.65bn from Rs 0.7bn in FY15. Its content cost was Rs 3.2bn, indicating that the company was not able to recoup its investment in content only through advertising revenue. Novi also spent Rs 1.6bn as selling and distribution expenses in FY16, which indicates that the initial operating expenditure is very high in order to sustain eyeballs.

As a rule of thumb, every 20 minutes of a scripted show costs Rs 1mn and non-scripted shows cost Rs 2-3mn. Hence, to provide the subscriber with a seamless service with decent content options, an OTT provider needs to have at least 300-400 hours of content (scripted, non-scripted, and movie included). Hence, the content cost to run an OTT platform on a per-annum basis would be at least Rs 3-4bn – an investment that is not viable for small-scale and standalone OTT operators. Hotstar, with strong parent backing and ample funding access, can afford to invest aggressively in content and experiment with various revenue models before becoming self-sustainable.

OTT revolution is an opportunity for the content providers

Where there are eyeballs, there needs to be content and Over-The-Top (OTT) service providers globally have emerged in the past two years for filling in those needs. In India, as the market for OTT content continues to grow, standalone OTT providers will have to capitalise on changing consumer preferences and interests, and combine these with a compelling user experience to build a fast-growing and very loyal paying fan base. Consumers expect to stream latest videos in high definition without buffering. With sports being streamed live online as well, consumers are beginning to expect the same uninterrupted live stream, and to download videos in high quality.

Conclusion

With faster 4G internet speeds, affordable data plans, and increase in smartphone penetration, OTT players that create the right exclusive original content, and play seamlessly on all four screens (smartphones, tablets, laptops, and televisions), with high-quality stream options (HD, ultra HD) – all at the right price-point – will be the winners of tomorrow.

Lack of much needed infrastructure is an almost debilitating condition for a fast-growing economy like India, a country that has nevertheless seen both volume and ‘strength’ growth in digital channels. Given the large, educated, young population with rising income levels, these changes (internet penetration, consuming video on the go) should be expeditious, but the reality is stark – broadband connectivity in India is not strong and internet penetration is low, especially in rural areas. Regulatory delays are another significant hurdle in the path of connectivity. Acquiring content rights for a new distribution platform such as OTT is undoubtedly challenging, given OTT’s unproven nature, faster change in consumer habits, and time taken for subscriber growth. Content owners have an additional challenge in maintaining a delicate balance between new opportunities and their existing relationships with distribution and marketing partners.

Currently, launches of multiple OTT platforms provide immense opportunities for niche content providers, as they can now leverage on changing video consumption patterns and target their prospective audience, which was otherwise difficult due to their lower bargaining power vis-a-vis the traditional linear TV platform. Global majors like Netflix and Amazon Prime, who are targeting India for the next leg of their subscriber growth, need to invest in local content due to limited appetite for English content. They need to tie up with local content production houses to fill in the gaps in their portfolios – a win-win situation for both parties.

Similarly, OTT platforms also provide an opportunity for traditional broadcasters to experiment and invest in niche content, as they now have an additional platform to not only reach their target audience, but to also increase their revenue streams – precisely the reason why most broadcasters are now investing in original content for their OTT platforms.

With Reliance JIO offering data at competitive tariffs, and other incumbent telecoms service providers following suit, mobile broadband penetration (made available at an affordable price) is going to increase at a rapid pace. Hence, bandwidth cost will no longer be a deterrent for consumption of online video (1GB of data is now available at Rs 50, which is sufficient for three hours of mobile video consumption). With one of the major hurdles now being removed, it is a matter of time before the industry discovers the best way to run this emerging business in a profitable way. Until then, participants will continue to experiment with various business models and players with deep pockets will keep emerging and forging ahead. Broadcasters with huge content libraries and IP rights of lucrative sports properties are already a step ahead of other OTT players. With changing video consumption patterns, multiplication of viewing devices, and an appetite for niche local content, there is enough space for standalone OTT players to flourish and thrive.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access