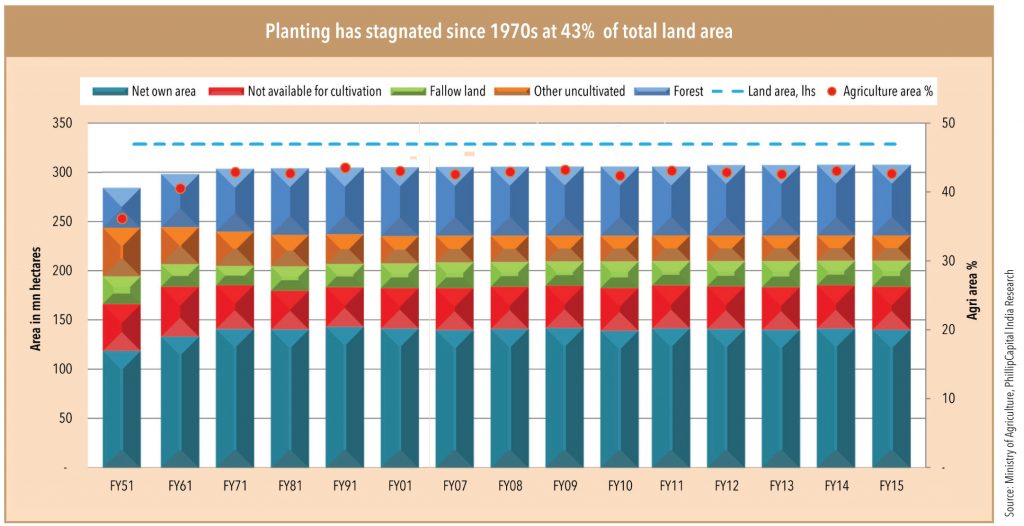

The Green Revolution in India happened almost half a century ago! Yes, you read that right. The biggest paradigm shift in Indian agriculture happened that long ago and there haven’t really been any revolutions since, just slow and steady progress towards self-sufficiency and world records in production of several agricultural commodities, and a just as steady escalation of problems.

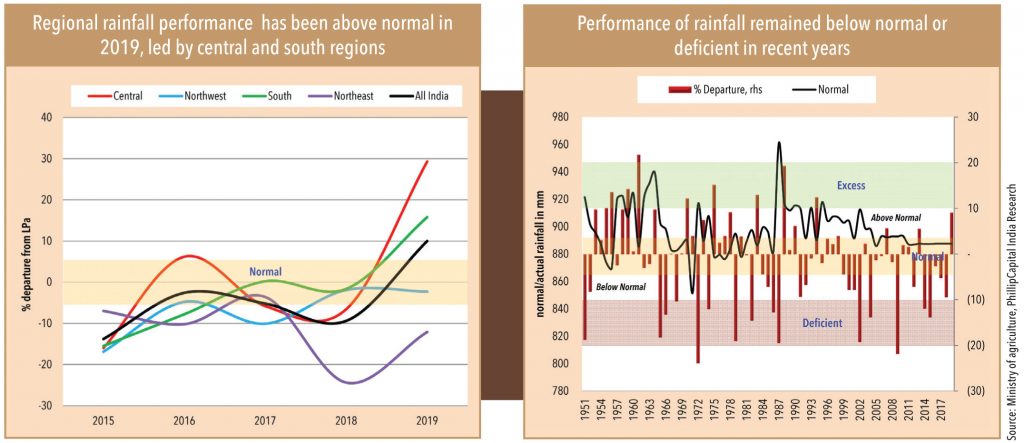

Some are surmountable – such as inadequate irrigation, shrinking landholdings, over usage of urea over other nutrients, and shrinking farmer margins. And some, such as erratic and inadequate rainfall, are indirectly surmountable with planning and implementation of schemes that support farmers.

This report takes a closer look at what is happening at the farm-level, what the farmers feel about various issues, and what the various stakeholders such as government officials and agro-chem manufacturers saying. The report also attempts to shine a light at how changing consumption patterns are driving a structural shift in Indian agriculture, not quite a revolution, but not a quiet change either. The new developments are bold, they are beautiful, they are daring, and there is a good chance that they will leave Indian farmers much more empowered than before.

Ongoing policy concerns in procurement, storage, and pricing are affecting farmers

Agriculture in India is not easily lucrative

The GV team travelled and interacted with many stakeholders in India’s agriculture sector to understand what is really happening on the ground. It seems that barring rich farmers in a few states, most farmers are finding it difficult to earn even reasonable returns. Farming as a business has lot of uncertainty and a major one is dependency on the monsoon. Mr Agrawal, a large distributor of agrochemicals and fertilisers from Chandigarh, said that “Farming is not an easy task. If you lose 50-70% of your produce because of rains or any other reasons, farmers can forget about profit.” Mr Patel, a fertiliser distributor in Vadodara, takes up a challenging stance while talking about agriculture – “I am happy to offer you Rs 1,00,000. Will you do sowing for paddy next season? I just need a return of 10-15%,” he smirks, trying to convey that farming is so fraught with risks today that a person with a non-agriculture background almost always stays away. He believes that non-farmers have misconceptions about the level of farmers’ earnings and the so-called freebies that they receive from the government and other agencies.

Government support present, but not enough

There is no doubt that government support over the last many decades, and the efforts of the farmers themselves, has helped India register a four-fold jump in food-grain production to 285mn tonnes in 2018-19. However, despite this growth, farmers find it difficult to make decent returns because of various reasons. The primary reason is heavy dependency on monsoon for a major share of water requirement, which is why erratic rainfall often reduces crop yields and production. Traditional government policies of procuring and storing only rice and wheat often limit farmers’ realisation because many farmers still tend to stick to these crops mainly just because of habit, lack of education and information, and historical government focus. In fact, when the monsoon is good, the crop production is higher and farmers’ realisations drop as they sell at below MSPs and do not get ‘true realisation’ – because of several reasons.

“If agriculture goes wrong, nothing else will have a chance to go right in our country”

– Mr M S Swaminathan, father of India’s Green Revolution.

Positive structural changes

Among positive structural changes in agriculture are the gradual changes in sowing patterns; farmers are increasingly opting to grow more pulses, cereals, or horticulture crops in order to earn better returns. In Maharashtra and many southern states, sowing of fruits and vegetables is becoming very important, mainly because of shortage of rainfall and lack of good irrigation facilities. Of course, changes in lifestyle or eating habits are also structurally supporting the higher prevalence of horticulture crops. The government is focused on crops that consume less water as only about half of India’s agricultural land is irrigated. Also, crop diversification supports the profitability of farmers.

No quick fixes – several questions prevail

Changes in agriculture are taking Indian agriculture and farmers in the right direction – towards better earnings. But the process is slow and there are no quick-fixes. The government will have to have a long-term outlook and provide growth visibility by leveraging various policy measures, including income-support schemes, crop insurance, major irrigation projects, soil health card, and DBT. Both structural changes and ongoing concerns have led to changes in consumption patterns and product mix over the past few years. Several questions prevail – what are the most pressing concerns? How are farmers adapting to structural changes? How are government measures really affecting farmers? What are the growth opportunities for agriculture-inputs companies? This GV attempts to address all these questions and more. It covers the ground realities – from the farm to the firm and on to people’s dining table.

A brief history of agriculture in India

More than 50% of India’s population still directly or indirectly depends on agriculture and allied sectors – clearly showing the importance of agriculture in India.

• The known history of Indian agriculture begins as early as 9,000 BCE in north-west India with cultivation of plants and domestication of crops and animals. Double monsoons helped two harvests in a year, leading to multiple crops.

• Under the British Raj, few Indian commercial crops (cotton, indigo, opium, wheat, and rice) made it to the global market. Due to extensive irrigation with canal networks in Punjab, Narmada valley, and Andhra Pradesh, these places became centres of agrarian reforms in India. The British regime in India supplied irrigation works, but rarely on the scale required. Community effort and private investment soared as market for irrigation developed. Agricultural prices of some commodities rose to about three times between 1870-1920.

• Since India’s independence, the country has built self-sufficiency in basic food crops with the government’s policies (Green Revolution), reforms, and the effort of India’s farmers. Five-year plans for agriculture development, land reclamation and development, mechanisation and electrification and use of chemicals (largely fertilisers) were also initiated.

• India relied on imports and food support to cover domestic requirements before the mid 1960s.

• A severe drought in the mid-1960s led to reforms in agricultural policies via several initiatives such as the Green Revolution and adoption of high-yielding varieties of crops. In fact, several programmes were undertaken to improve food and cash crops supply – 1940s : Grow More Food Campaign; 1950s : Integrated Production Programme. Several other measures were taken to improve crop production such as Yellow Revolution (for oilseeds in 1980s), Operation Flood (dairy in 1970s) and Blue Revolution (fishing in 1970s).

• India eventually built self-sufficiency in basic food crops. Larger beneficiaries were states such as Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh – that benefited and supported the most in the Green Revolution mainly because they had larger irrigated areas. They are now considered the country’s bread basket.

• With successful productivity gains, farmers started focusing more on crops such as oil seeds, and fruits and vegetables by the 1980s along with other activities such as dairy, fishing, and livestock.

• New varieties of crops needed higher fertiliser usage, so, the government formed cooperative societies such as IFFCO.

Nowadays, the government is focusing on newer areas such as agro processing and biotechnology.

Some interesting facts

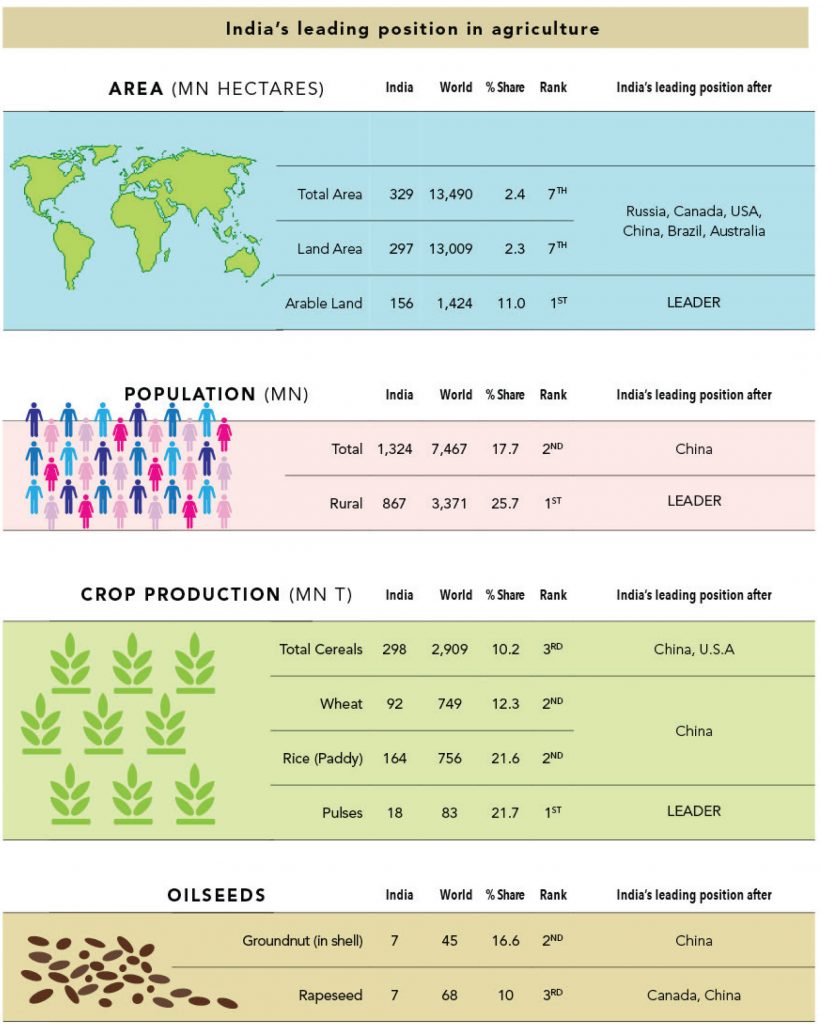

• India is still an agrarian country, if not an agrarian economy. It holds the #1 spot in arable land in the world, with a share of about 11%. It is at 7th place in terms of land area, and uses c.53% of its land for agriculture. India has the largest rural population with a global share of 26%.

• Because the share of agriculture land usage is high, there is major dependency on agriculture and its allied sectors for employment and livelihood.

• However, agriculture’s share towards GDP continuously declined since independence from about 50% to about 15% presently. Rapid growth of industrialisation and focus on the service sector with an increasingly educated population are major reasons for this.

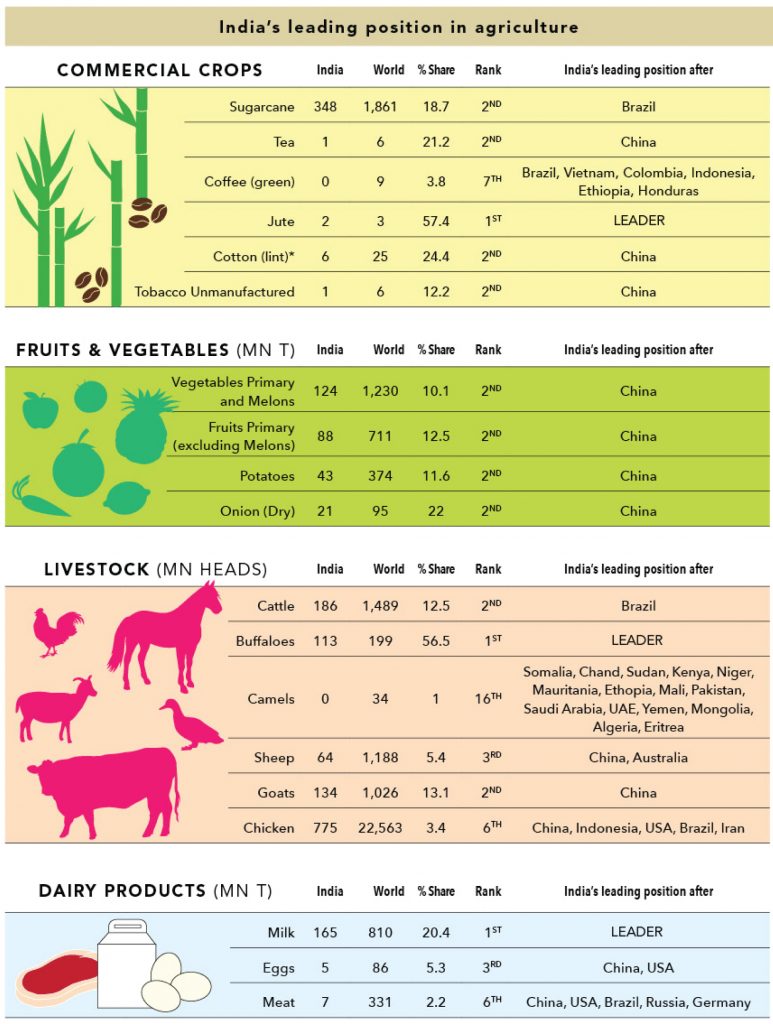

• In terms of crop production, India is only next to China with a focus on cereals (rice and wheat), oil seeds (groundnut and rapeseeds) and fruits/vegetables.

• India is the largest milk producer globally, with a share of about 20% and this is due to its #1 position in buffalo stocks (113mn; global share of 56%).

• Despite a rise in agriculture production, its share in India’s GDP is continuously declining on rapid growth in services, and industrial and non-agriculture sectors.

“Agriculture will remain a necessary part of the Indian economy. Its direct and indirect dependence is significant. Today, we are eating much more affordable food, and that is only because of self-sufficiency achieved over the past few the years”

– Mr Arora, a marketing representative of a large fertiliser company in Uttar Pradesh

Hurdles abound

Over the years, India has gradually become self-sufficient in crop production, from being an import-dependent country, particularly for rice and wheat. It is now one of the leading countries in many categories of food production.

Indian agriculture is more diverse than other countries in terms of soil quality, land holding sizes and cropping patterns. Also, Indian farmers depend on monsoon as only c.48% of India’s farming land is irrigated. There has been a drought-like situation in several parts of Maharashtra over the past 2-3 years. Sometimes, unseasonal rains also destroy standing crops, leaving farmers with huge crop losses. Availability of agriculture inputs at reasonable prices and farm laborers is another complication. Farmers receiving reasonable realization is not a given, and their profitability tends to vary from season to season and year to year. “It (farming) is a very difficult business, Sir. It requires hard work, constant investment, and risk-taking ability. Lack of education and traditional land holding forces farmers to remain attached to agriculture. Forget profit, it is difficult to recover cost nowadays,” said Mr Mamniya, a distributor of agriculture inputs at Satara, Maharashtra.

A selective approach (focused on rice and wheat) and constraints such as availability of resources, regional diversity, small landholdings, and high dependence on rainfall are hurdles in the way of India’s long-term agriculture sustainability.

Farmers do not have much control over realisations, so they focus on costs to increase profitability

Government initiatives are not enough, politically driven

The government has come up with several policy initiatives to mitigate some of the problems surrounding Indian agriculture. However, these measures are often taken to further state and central government political agendas. What is quite clear is that half-hearted reforms only support select farming communities. “We need some visible and long-term measures. Ultimately, farmers are the best judge of any scheme. So, if we see a farmer’s income is growing, then policies are good, but this should be sustainable. I believe the government’s intentions in recent policies are sincere, and I hope it will benefit our farmers in the long term,” said Mr Dubey, a distributor of agrochemicals in Haryana.

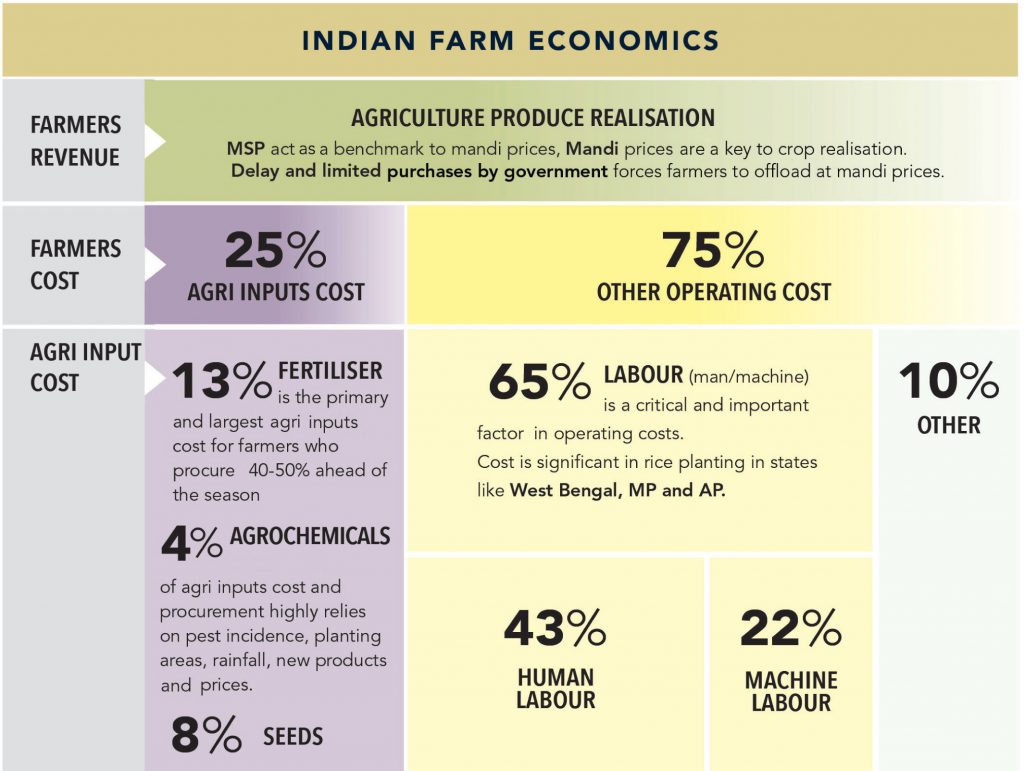

Mandi prices determine true earnings

To understand farmers’ financial health, affordability (how much they can afford), and profitability in India, one must understand farm economics. Farmers’ earnings (cash inflows) are mainly determined by mandi prices (market prices – mainly wholesale) or the MSP (Minimum Support Prices set by the government). While mandi prices generally remain in line with MSPs, with the arrival of fresh production, they tend to fall below them. Because the government procures only limited volumes (25-30%) of India’s total farm production at MSPs, mandi prices determine the true earnings of farmers.

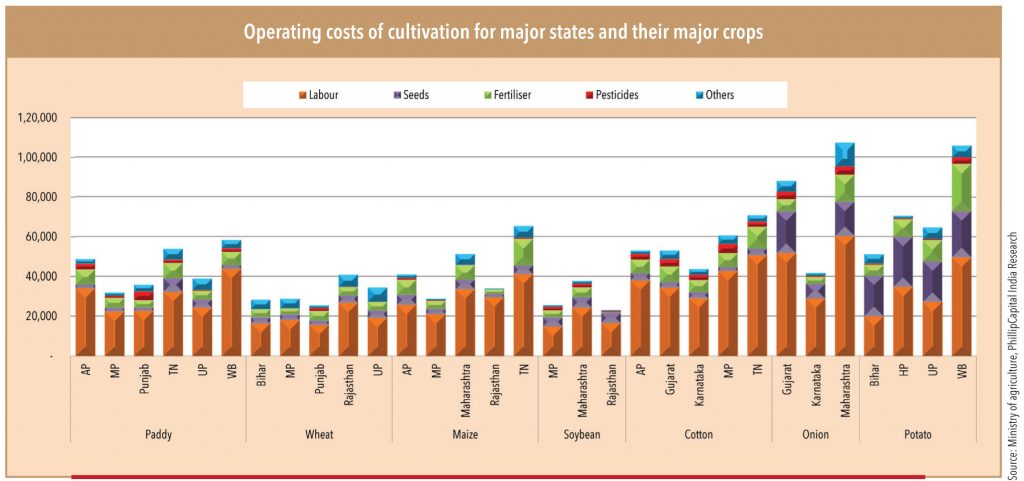

Labour dominates

Operating costs are dominated by labour charges in India at c.75%, including human/machine labour and irrigation charges. Rising urbanisation, or villagers switching towards alternate employment, is continuously creating labour shortages, leading to rising wage costs. In fact, this is a common concern for the entire emerging world, which is increasing demand for pesticides (herbicides) in a big way.

India’s land-holding patterns are skewed towards small and marginal holdings. These small and marginal farmers have to first look at labour costs before making decisions on other major costs such as agriculture inputs. “Small farmers have very limited cash and land areas both. That’s why they can’t afford tractors or technology. In any case, it makes no sense for them to spend on tractors for their small land holdings. Using labourers is the only option for them,” said a marketing representative of Hindchem Corporation, a bio-fertiliser company based in Mumbai.

Operating costs are most important in the cost of farming, and as labour cost has the largest share in these, it plays an important role in determining profits

Agriculture inputs – fertilisers, agrochemicals, seeds

Agri inputs mainly cover seeds, fertilisers, and agrochemicals – together accounting for c.25% of total farming costs. While usage varies by crops and states, these inputs are largely consumed for paddy, wheat, cotton and fruits/vegetables.

• Fertilisers is the largest cost component at 50-55% within agriculture input costs; it holds 13-15% share in overall operating costs of cultivation. Proclivity of farmers towards urea procurement is higher than it is for complex fertilisers (NP/NPK/NPS) due to the former’s lower prices – DAP is 5x more expensive than urea.

• Agrochemicals account for 15-17% of total agriculture inputs costs. Consumption levels in India are one of the lowest at c.300gm/ha compared to the world average of 4kg/ha. Farmers’ procurement depends on multiple factors such as pest incidences, sowings areas, distribution of rainfall, and price.

• Seeds account for c.33% of total agri input costs.

Rice (paddy) and wheat

• Rice and wheat are part of India’s primary food requirements and cover 75-77% of food grain production.

• Kharif season (monsoon plantation) is mainly identified with paddy (rice) and rabi (winter plantation) with wheat. For both seasons, major producing states are Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and West Bengal.

• For rice cultivation in Tamil Nadu, agriculture inputs are 30% of operating costs with a major contribution from seeds. In West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh, labour costs have a larger share.

• It is different in the richer agri states. “In Punjab or Haryana, most farmers are rich. Naturally, sowing as well as agriculture inputs consumption is high. Both states can afford to use more technologies compared to any other states in India,” said Mr Sharma, who works with a large agriculture inputs company in Madhya Pradesh.

Corn (maize)

• Within input costs in corn production, fertilisers account for c.20% (major consumer) vs. c.13% for rice and wheat, but pesticide usage for corn is very minimal at less than 1% of input costs.

• Over the past few years, corn is becoming an important crop after rice and wheat (c.65% share in cereals) with increasing usage in feed, food, and industrial non-food products (mainly starch).

• Feed for poultry covers a large share (c.50%) in corn consumption followed by feed for livestock.

• “Changing dietary patterns towards meat, government’s emphasis towards non-traditional crops, and some contribution for ethanol fuel is supporting corn,” said Mr Sharma, who works with a large agri-inputs company in MP.

• Corn is grown throughout the year, but c.75% is produced in the kharif season in Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Andhra Pradesh.

• Because of high labour costs, cultivation costs in Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu are higher.

Soybean

• Soybean is considered a premium crop as it is a major source of vegetable oil and food. The government’s support for oilseeds (higher MSPs) and changing food habits (mainly towards a protein-rich diet) is helping soybean production.

• It is one of the faster growing kharif crops with a production of c.14mn tonnes.

• Major producing states are Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan.

• Farmers’ operating costs of cultivation areis similar to corn in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra.

• For soybean, seeds and fertilisers are important components for agriculture input costs, covering c.14%.

Cotton

• India is a leading producer of cotton. It is largely a kharif crop with a 6-8-month maturity cycle and its sowing depends on factors such as soil, temperature, climate and irrigation.

• “Cotton is a very dynamic crop. Frost is its enemy; it needs temperatures of 21-30 degree celsius,” said Mr Patel, a large agriculture-inputs dealer in Anand, Gujarat, a state that is India’s leading cotton-producer (one-third share) followed by Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Madhya Pradesh. “Gujarat is the most preferred state to produce cotton because it has the right temperature, soil, availability of water and agriculture inputs. Gujarat’s leadership in textiles is highly dependent on its cotton production,” said Mr Patel.

• Cotton has the second-highest pesticide consumption after paddy, covering about 6% of agriculture input costs.

Onion

• Recently, onion prices went through the roof. “Excess rainfall damaged standing crops in larger areas, creating shortages. Prices will come down once domestic supply stabilises and imports begin (were to start by January),” said a Nagpur-based onion farmer at the Kisan Fair 2019 in Pune.

• India is the second-largest onion-growing country in the world with a production of c.23mn tonnes; production is round the year.

• Onions are majorly harvested after the rabi season (March to May) and major states producing states are Maharashtra, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat – these cover c.65% of India’s production.

• In onions, seeds are a major contributor to operating costs with a share of 19%, second-highest after potato.

Potato

• Potato used to be called a poor man’s friend and has been grown for 300+ years. It is known for its widespread availability, affordability, and its usage in various Indian dishes.

• It grows throughout the year (Kharif: September to November. Rabi: December to March), but rabi harvesting covers a major share.

• India is the third-largest potato producing country in the world, at 52mn tonnes.

• Three states – Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Bihar – produce c.70%.

• Potato is a high consumer of agriculture inputs with seeds having a major share at about 32%.

The Commission of Agriculture Costs & Prices (CACP) in the Ministry of Agriculture recommends MSPs for 23 crops (kharif and rabi). The aim is to keep MSPs at 1.5x production costs, taking into account the demand and supply situation. However, this methodology has been criticised. “Current MSP methodology does not reflect the present situation of farmers. CACP only undertakes projections based on state-wise and crop-specific estimates based on Ministry of Agriculture data. And, this data is three years behind, which means the cost escalation in inputs for farmers is not reflected in MSP,” said Mr Rao, a marketing officer a the Adventz Group.

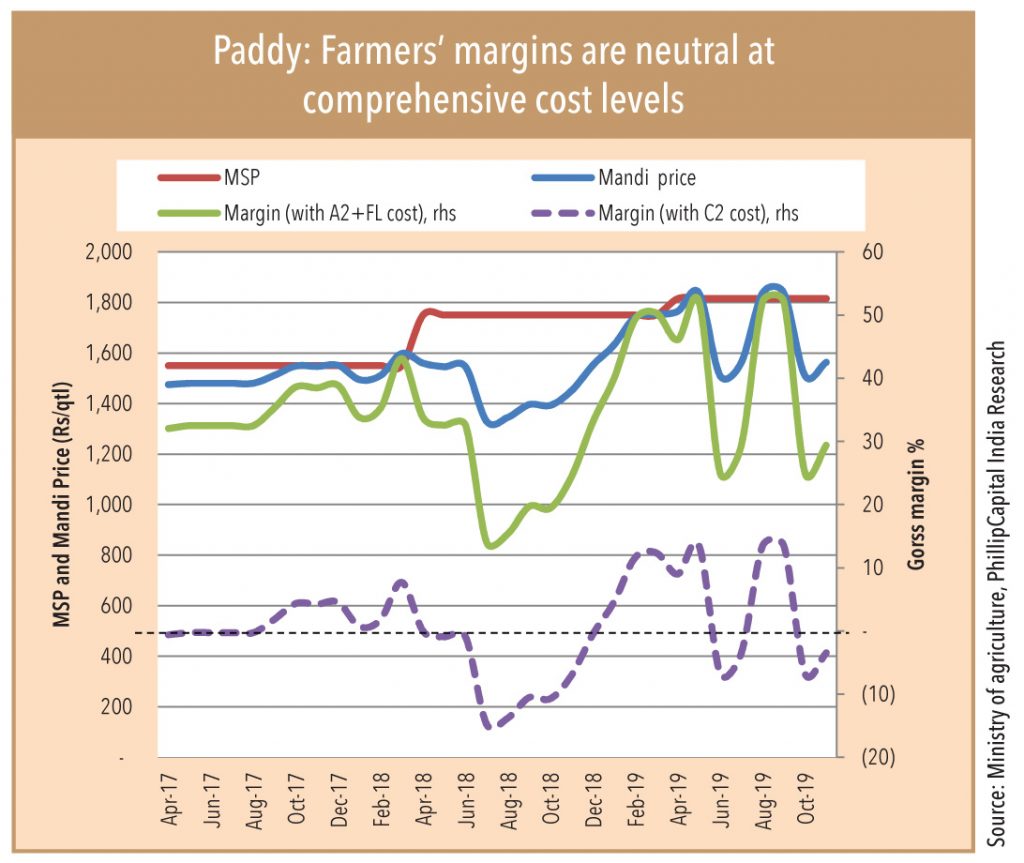

The government maintains that it reviews MSPs every sowing season to ensure that farmers receive adequate realisations. The CACP determines production costs of crops based on A2+FL (A2 = cost of agriculture inputs, hired labour, fuel, irrigation and other inputs costs. FL = value of unpaid family labour) and C2 (comprehensive costs covering interest cost, rental cost, owned land and fixed capital costs, above A2+FL). Government aims to keep MSPs at 1.5x of A2+FL cost rather than C2 or comprehensive cost.

So, observing incidence of crop losses caused by uneven rainfall, continuous rise in input costs, and limited compensation via crop insurance, it seems like farmers’ realisations are limited. Keeping MSPs at A2+FL cost does not seem to be compensating farmers adequately.

“Agriculture is the prime source of income for us. Our aim is to get some profit so that we can plan future sowing. Rising costs and no compensation for losses forces us to take loans at high costs. If there are two or more back-to-back poor seasons, then our high-interest loans keep on rising,” said a small farmer in Uttar Pradesh who was busy with wheat and potato sowing.

Looked at two major crops – rice (kharif) and wheat (rabi). Aim was to determine farmers’ gross earnings.

Paddy

• Mandi price for paddy remained below MSP for most months over the past three years. At mandi prices, farmers’ gross margins considering A2+FL costs are at 35% in the past three years.

• Paddy is considered to be a risky crop due to its high dependency on monsoon, and therefore, farmers’ earnings are highly determined by monsoon prospects. Untimely rain increases the chances of crop damages.

• Considering comprehensive cost, farmers are not making any profit on an average for the past three years. This seems to reflect the general picture of farmers’ earnings for paddy crops. However, it will vary from state to state and sowing areas. For example, farmers in Punjab/Haryana or western Uttar Pradesh will not be affected much, and earn a reasonable profit because irrigated farms stand at +90% in these states compared to India’s average 48%.

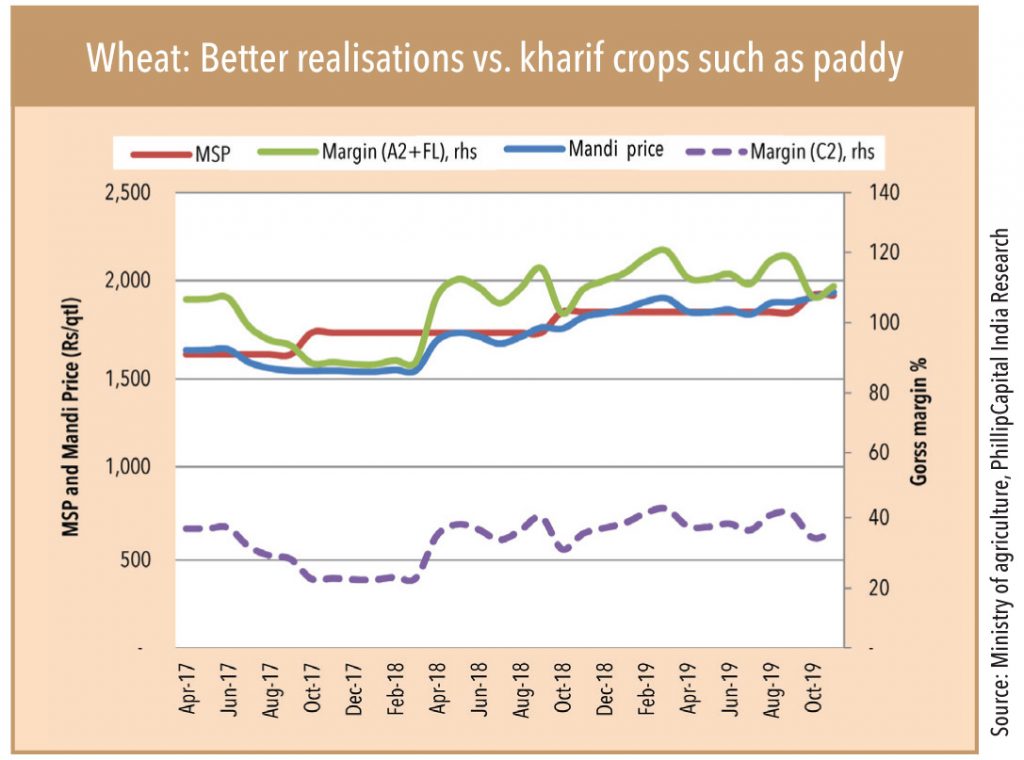

Wheat

• The prospects of this crop largely depend on moisture levels in the soil. A normal monsoon or an extended monsoon (beyond September) during kharif season increases the yield and profitability of wheat.

• Chances of crop losses are limited vs. kharif season – due to limited dependence on monsoon.

• MSPs have remained above mandi prices over the past three years.

• At mandi prices, farmers’ gross margins considering all comprehensive (C2) costs were at about 35% in the past three years, but considering costs at A2+FL, they increased to 100% of mandi prices.

Storage and procurement: Important for farmers’ profitability

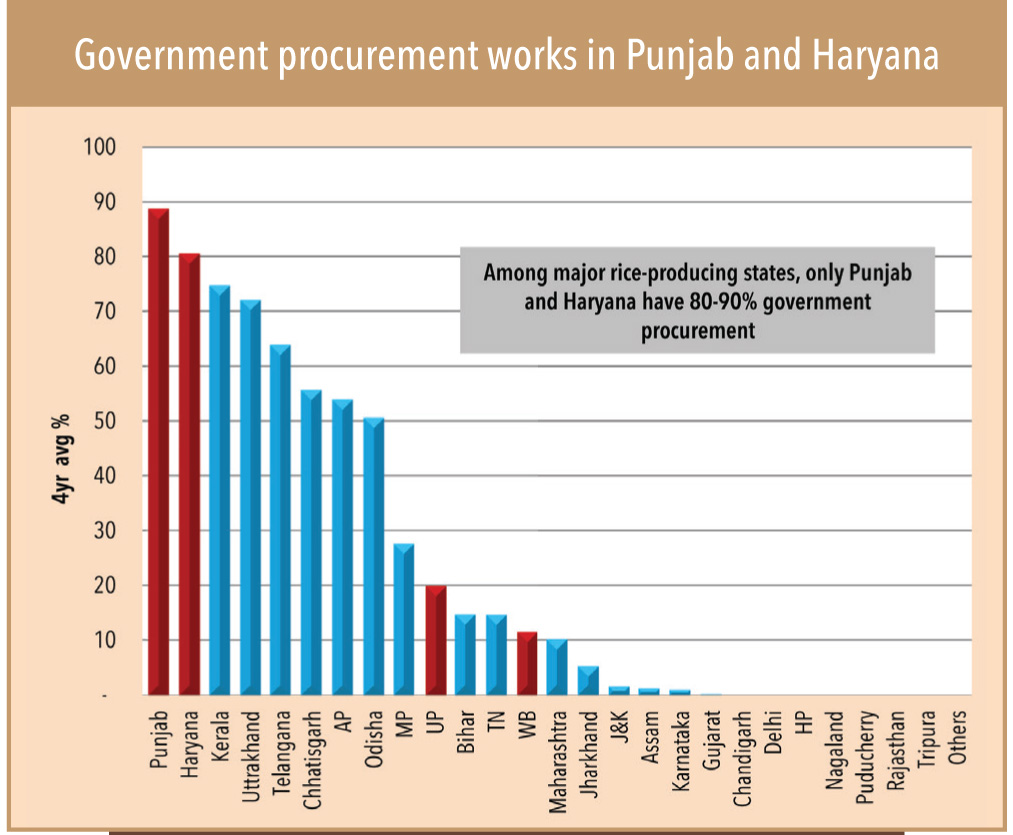

Government procurement and storage of crops plays an important role in determining farmers’ true realisations, as mandi prices are often below MSPs. Traditionally, government procurement is largely focused on traditional crops such as rice and wheat, mainly to have food security in the country.

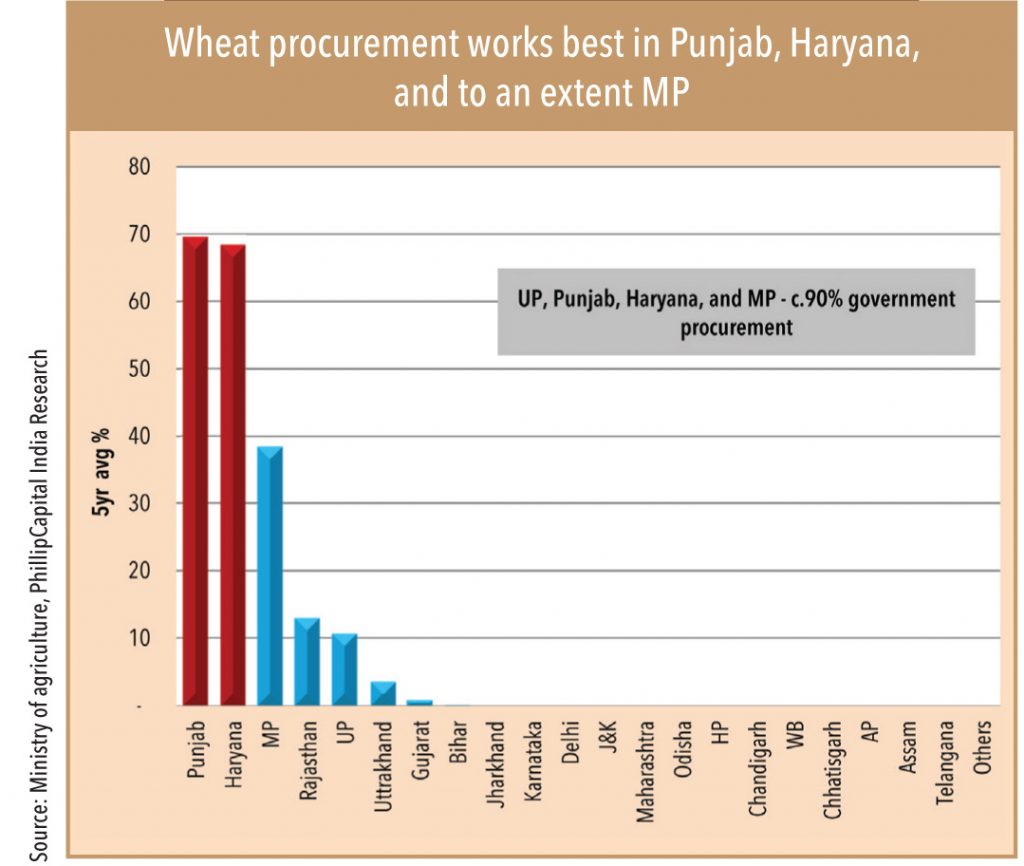

Government data suggests that procurement is only 20-25% of production and largely only in select states such as Punjab and Haryana. “Punjab or Haryana, both are traditionally high crop producing states – whether it is wheat or rice. So, procurement is also high and storage facilities are also built by government agencies such as Food Corporation of India (FCI) or state agencies,” said Mr Dubey, a marketing representative working with a large fertiliser company in Haryana.

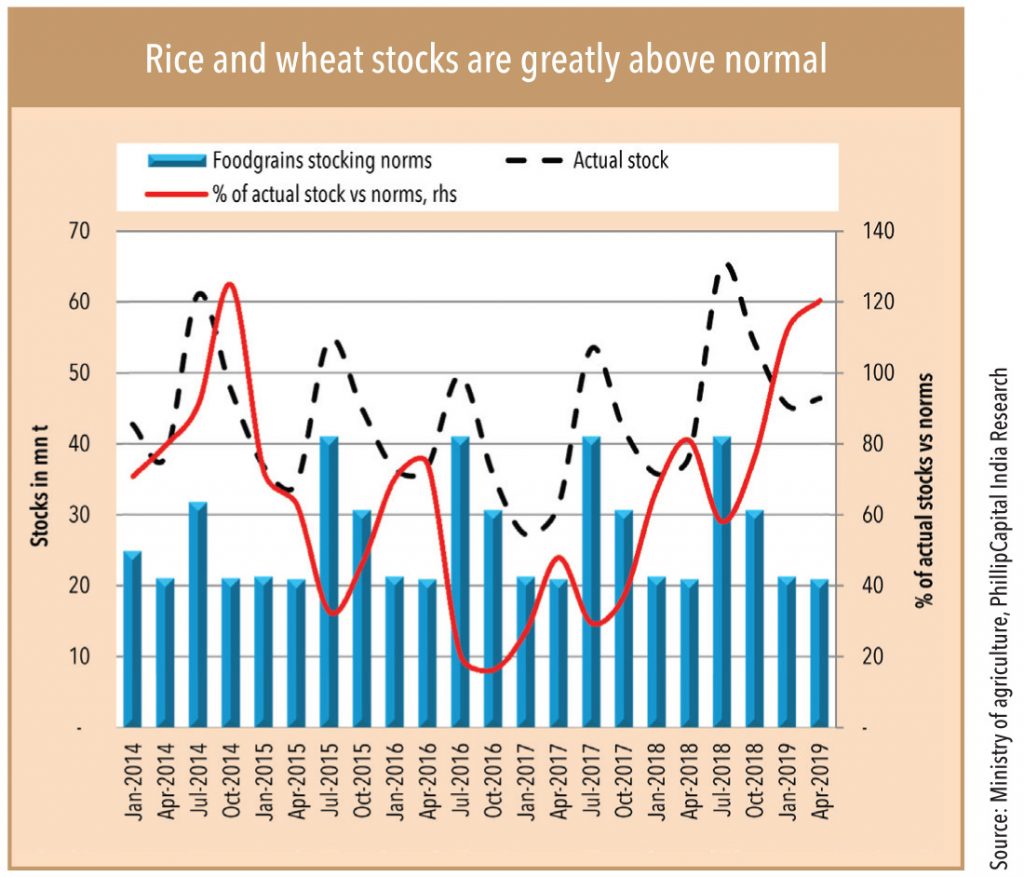

Government agencies (FCI and state agencies) largely store rice and wheat in order to maintain buffer inventories for food security, demand/supply management, and controlling prices. Continuous bumper harvesting of rice and wheat over the past few years has forced government agencies to store inventories that are much above (1.2x) set norms of about 20mn tonnes..

Government procurement process not easy for farmers

• The government has many criteria to buy at MSPs from farmers – the most important one is quality. Farmers have to visit dedicated procurement centres (additional freight costs).

• Procurement is for food grains mostly, farmers producing a variety of crops need to spend additional money on freight.

• Sometimes, farmers are also forced to sell at mandi price because they have to repay a loan taken from the buyer itself (loan against crop produce).

• The role of MSPs becomes less relevant with selective procurement (beyond rice/wheat). So, farmers don’t have much choice and are forced to sell non-traditional crops such as grains/fruits/vegetables at mandi prices to get quick money and start preparing for the next season.

Poor procurement and selective crops storage indicate poor management by the government.

Monsoon still remains the key driver for successful farming

It has been over seven decades since independence, and Indian agriculture still largely depends a lot on the monsoon season for its water supply. Many experts attribute this to very little investment in irrigation projects, growing population and industrialization, and increasing cropping areas. Within the season, distribution of rainfall plays an important role in determining the success of that year’s crop.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access