Questions on sustainability of existing ecommerce models?

The jury is still out on the sustainability of existing ecommerce models in India. However, one thing that most experts concur on is that a lean model is likely to make money. The likes of Ebay and Alibaba have been profitable because they are pure ecommerce facilitators offering technology solutions and logistics support to buyers and sellers. But the economics of ecommerce is still suspect according to some experts. One of the experts whom we interacted with gave interesting insights into the current business models. He says there two primary costs for a pure ecommerce model:

1.Cataloguing costs: These are the costs associated with creating online catalogues. The photographing cost for one SKU is Rs 1600-1700. If this were to be billed to the brand, it is unlikely to offer the product on consignment to online players.

Amazon India has 3rd party providers who are trained on Amazon’s imaging and cataloguing guidelines and assist you in creating high impact listings. They also have preferential rates and offers for Amazon sellers

2.Operating costs (% of GMV):

a. Marketing: 14-15%

b. Man power: 7-8 %

c. Logistics: 10%

d. Corporate: 5%

According to the expert, “An ecommerce player needs to have a gross margin of at least 40%, but because a reseller seldom earns 40% margin, there is the need to have private labels. The only other way to make money is when other players have dropped off and you are the last man standing. Then, attaining scale can drive operating leverage. If a player has a GMV run rate of US$ 1bn and losses of US$ 200mn, then mathematically,they have to do US$ 6bn (at 5% commission rate) in GMVs to break even as most costs (as mentioned above) are variable.”

The industry expert adds that many of these businesses have had significant inventory write offs because in their scramble to offer range, brands, and assortment, they were left with dead inventory. A physical store has to write of 10-12% of its inventory after running an efficient inventory model. When one sells everything and every size under the sun, the inventory risk is huge. He claims that on the international brands retailed by some of ecommerce players, they carry over 1,000 days of inventory. He estimates that the amount of PE money written off in the sector would be at least US$ 1bn. He cites examples of acquisitions of online brands and portals which were then discontinued. The primary reason is that investment write offs of the investors (who are common investors in the acquirer and target) would get camouflaged under acquisitions. Some 50-70 ecommerce websites have gone down — some of the prominent ones are India Plaza and Yebhi.

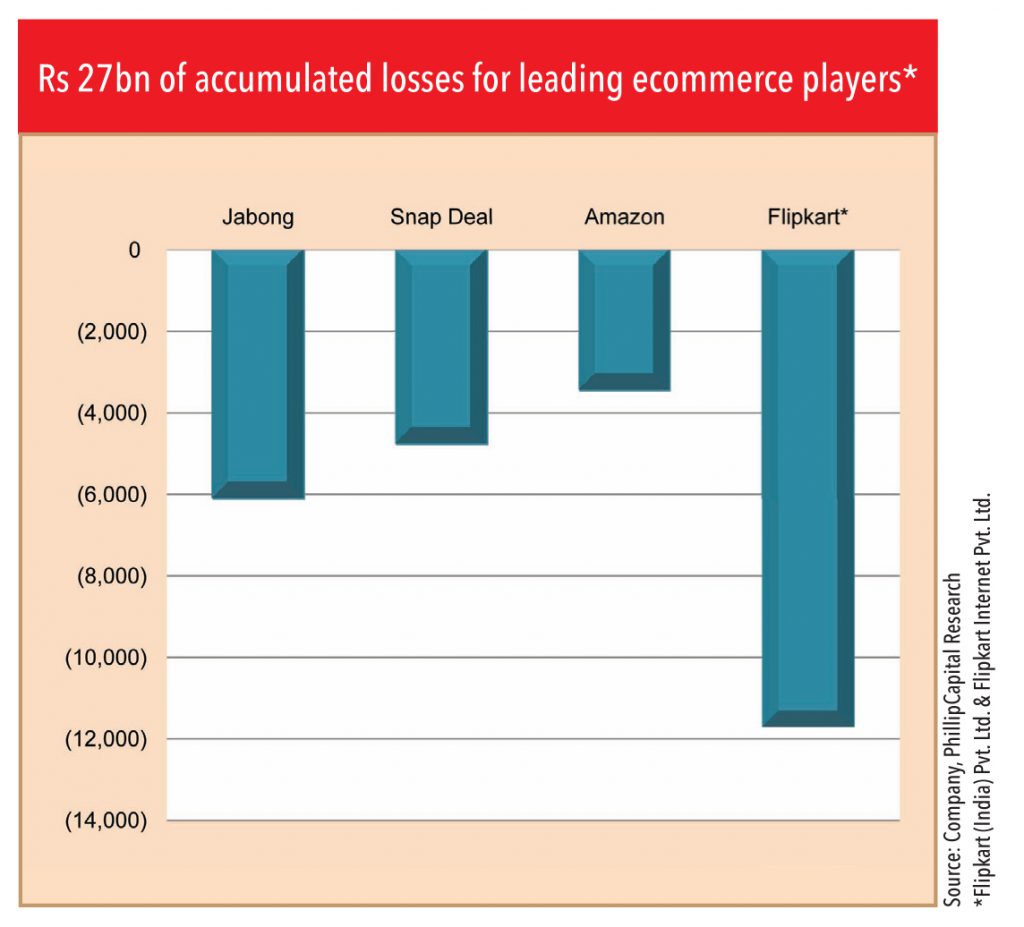

The cumulative losses of top-5 ecommerce players till 2014 (companies that operate the platforms and excluding their vendors and logistics arms if any) in India is Rs 27 bn. The losses could be even higher considering losses of critical vendors/suppliers, logistics manpower etc. which may have been created as separate legal entities.

Even Mr Bawankule of Google is of the opinion that out of the 150 websites started in three years, only 30 exist today. He says it is about technology, learnings, and an understanding of what works and what doesn’t.

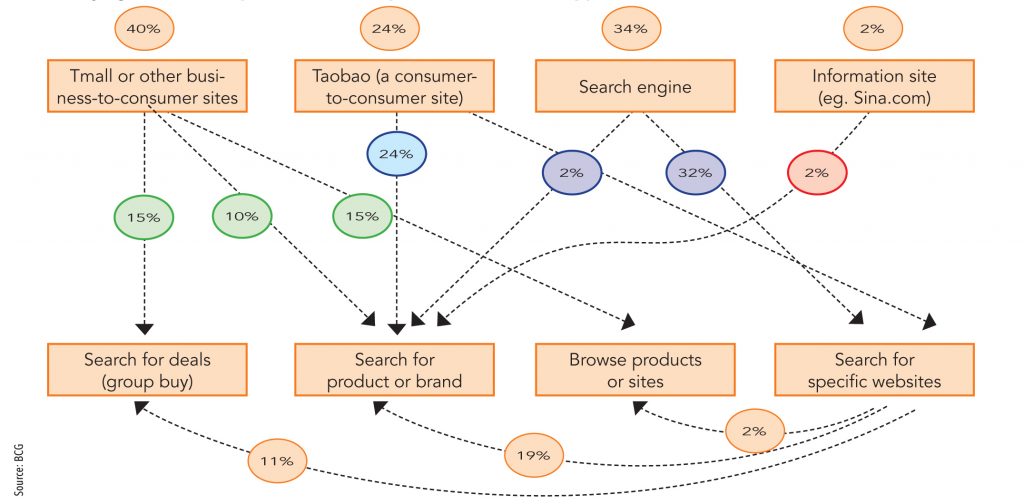

Then what is the right model for India where everyone makes money? An expert bats for a market place around brands like Tmall. He says the world’s second largest retailer Tesco’s ecommerce venture is turning into a marketplace. Tesco also sells brands that it doesn’t list in its stores. The whole space is about getting the customer to buy more categories. After spending Rs 1,000 (in the form of discounts) to acquire a customer, if he/she just buys a Rs 50,000 mobile and nothing else from the site, then the 4% margin on the mobile doesn’t even cover the marketing costs. It is when he shops for more products across the basket — from apparel to general merchandise on the same portal — the margin accretion is commensurate with the customer acquisition costs. Therefore, individual deep sites (selling only electronics or mobiles) which are visited only for specific purchases, are unlikely to be economically viable.

The expert says unlike most PE players who are betting on the last man standing game in this space, there will be at least 4-5 players in a free market like India. He sees immense opportunity on building a brands-centric market place such as Alibaba’s Tmall.

He believes there is space for an alternate marketplace,which will be driven by strong brands. Logically,any conglomerate which has its portfolio brands across categories can anchor this market place.

Snapdeal is one of the few pure-play market places that don’t carry inventory and are a pure B2C player modelled around ebay. Such players are likely to emerge as strong and long-term players in the industry.

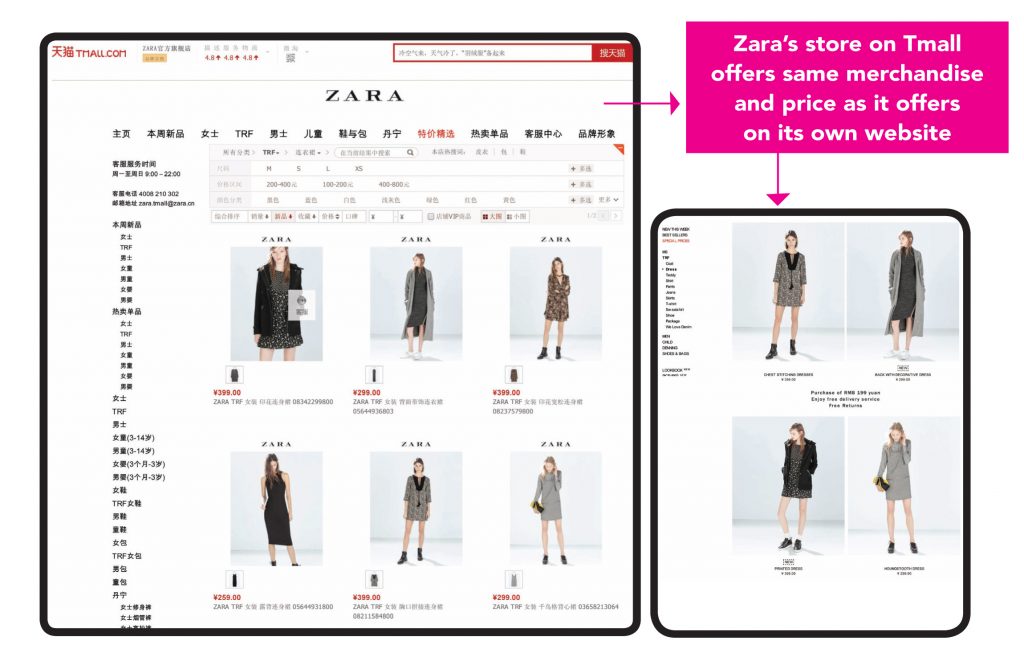

Tmall is so popular that even Zara in China entered Tmall in October 2014 to gain a stronger foothold in China. Zara has been operating its own ecommerce portal since 2010. It is interesting to note that Zara’s china website traffic ranking is at 6685 as against Tmall’s 5th rank.

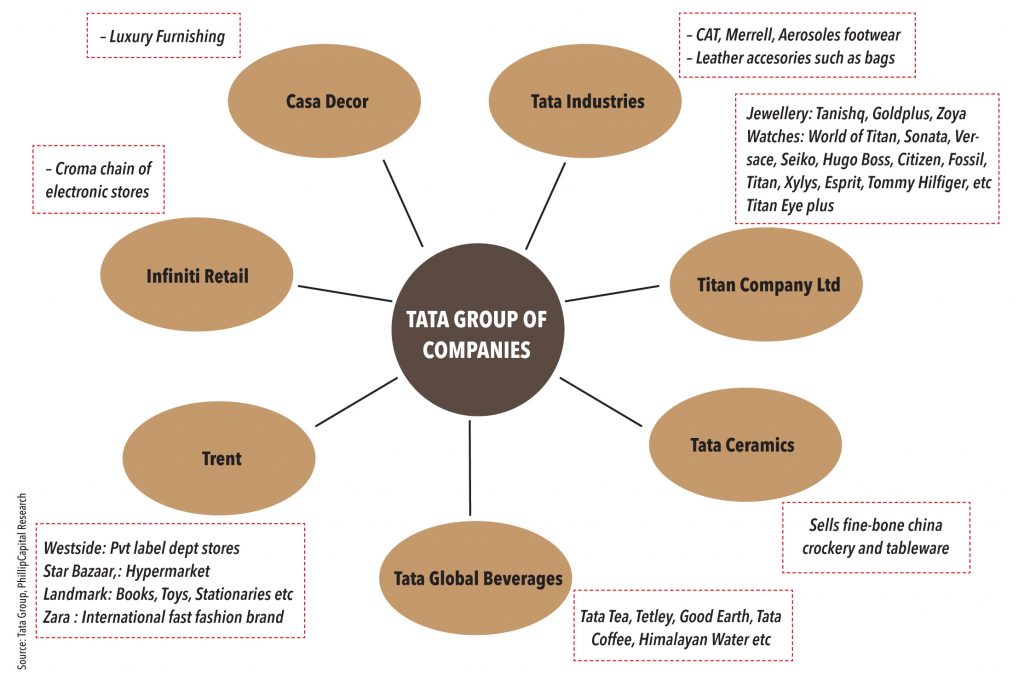

“The Tata group has such a wide presence that logically it can anchor a market place — it depends on how it wants to position itself (single platform or multiple),” says Mr Bawankule of Google.

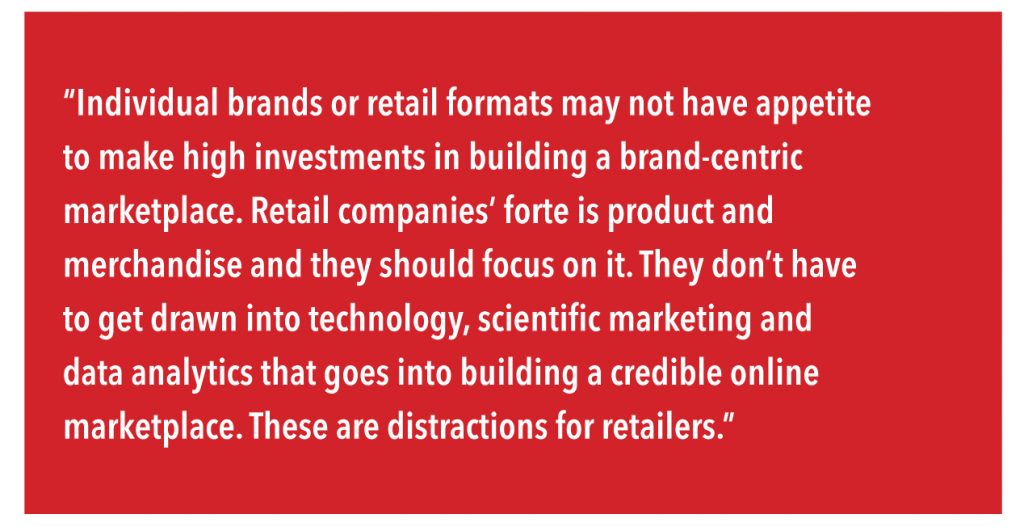

An industry expert explains, “Individual brands or retail formats may not have appetite to make high investments in building a brand-centric marketplace.Retail companies’ forte is product and merchandise and they should focus on it. They don’t have to get drawn into technology, scientific marketing and data analytics that goes into building a credible online marketplace. These are distractions for retailers.” But then, why hasn’t any major retailer abroad started its own marketplace? The industry expert says that, “Organized retail is 85% of the retail market in developed markets and hence retailers individually are of critical size and scale — it does not make sense for them to be marketplaces —it made more economic sense for them to evolve their own online business models — for example, Wal-Mart had 11.4% of US retail sales — no Indian retailer will be anywhere close to that number.”

The marketplace needs to have as many categories as possible. The Indian Tmall, with an omni-channel proposition, will be a unique offering. A marketplace is like a mall and will always draw more visitors than a standalone website (a store) selling one category. If a certain conglomerate is present in multiple categories,then it would be logical for it to anchor such a brand-centric market place and subsequently tie up with players in categories that are not in the portfolio.An expert emphasises that, “It is how efficiently one takes the brand to the consumer.” He cites the example of Aditya Birla and Tata groups, which can leverage on such platforms as they are present in multiple categories. The Tata group is present in all major categories from apparel (Westside) to books to watches and jewellery (Titan) and enjoys tremendous brand equity. Trent’s Westside is a private label driven departmental store and it controls the entire experience from the product to retailing. Titan’s Mia range (daily wear & small ticket sizes) of jewellery could find wider markets when sold online, supported by Tanishq’s strong store network, supply chain and customer trust. Tata group’s association with international brands such as Zara is an added advantage. The advantage a new player entering the market will have is that it can learn from the mistakes the existing players have made and hence the learning curve will be shorter, says the expert.

In a platform such as Tmall, responsibilities are demarcated and divided between brands and marketplace on the basis of inherent strengths and capabilities. Some of the things that brands have to manage will be pricing, merchandise range, and ecosystem. Brands will have to provide the full-range to the platform, while the marketplace manages the technology and logistics and sets up an omni-channel infrastructure. Therefore, the realisation per SKU is higher and margin shared will be commensurate. The absolute investment will be just 5% of what one would have incurred if it were to go omni on its own, as even the marketing expenses will be managed by the marketplace (due to the multiple categories it offers).

Customer acquisition for such a marketplace may be easier due to the existing loyalty programs of the brands under a group’s umbrella. Customers can continue to get loyalty on purchasing from this platform. Using points to buy other categories will be stage two, as the entire loyalty program needs to integrate.

Going omni alone has its pitfalls. When an offline retailer goes online, it’s not his forte or area of strength to operate a shopping website. There is always a channel conflict of offline vs. online – what stock to offer, how much discount to offer — all of these conflicts get addressed usually in favour of offline. Therefore, the online business grows in the shadow of the big tree. The online business requires a different mind-set and skill set hence has to be separately funded entity and with a team of specialists. That perhaps explains why Tata Group’s ecommerce initiative is said to be under Tata Industries and is being driven independently with a dedicated team of specialists.The venture is reportedly being put together by Ashutosh Pandey, former COO of Landmark and it has also reportedly roped in Sarvesh Dwivedi, who was heading the lifestyle division of eBay India.

One of the key draws for brands to participate in a marketplace or give preference to a particular market place is providing data analytics — for example, providing data on best-selling stocks to the brands. This helps the brands plan their next season’s inventory better. Existing market places don’t share the data with the brands as – their currency is customer data.

“In the month of October 2014, the 3 big online sales by Flipkart (including Myntra), Snapdeal and Amazon clocked a turnover of Rs 10 bn in the fashion category, accounting for nearly 5% of overall category sales for the period,” says Mr Sanjay Behl, CEO Lifestyle Business, Raymond.

Online players don’t have significant advantage on sourcing merchandise, says an executive with a national brand. Shopper’s Stop may carry limited lines due to limited shelf space. Online players don’t have constraints to display, but they still have to buy inventory. Online player are scouring products from mainline brands but brands are wary of launching new introductions and better lines online. For e.g., Van Heusen introduces new lines every week. Myntra or Jabong, like any other sellers with inventory models, have to buy from the brand — they will take a call on which lines to buy, thus narrowing the collection. Thereafter, if they get stuck with some inventory, it limits the ability to buy the next round of inventory, thus limiting the lines of the brand it can carry.

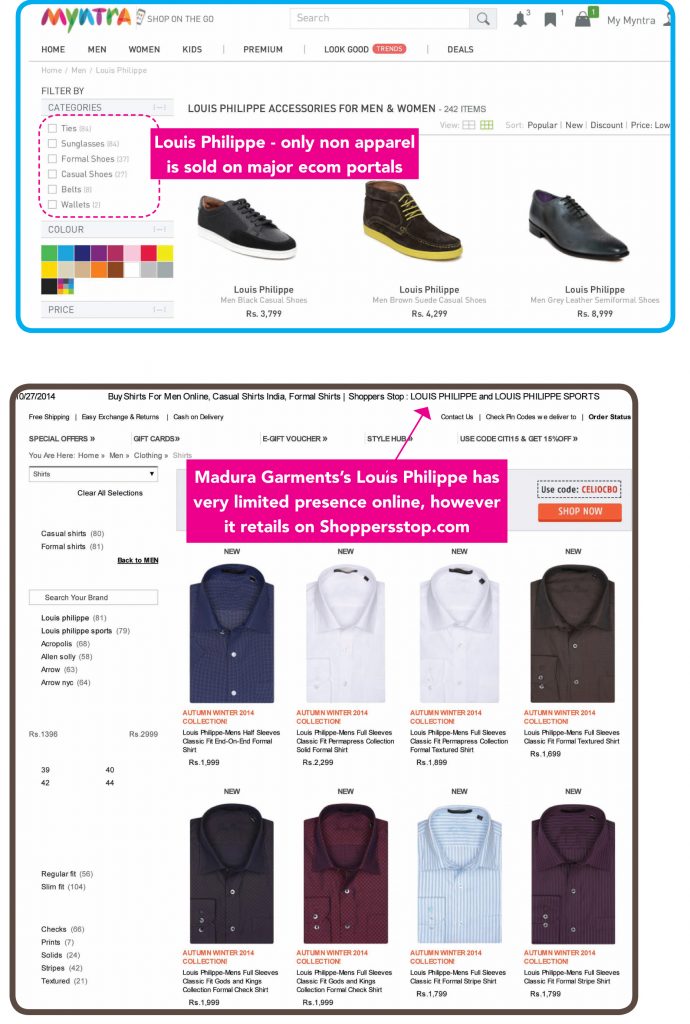

We came across interesting patterns and cues on brands and their relationship with ecommerce players.Madura Garments’ largest brand Louis Philippe doesn’t retail on Myntra, Jabong, or Flipkart. However it does retail on Snapdeal, courtesy a reseller. These are possibly measures taken by the brands to protect the brand image and the interests of its offline partners (from unreasonable discounting).

Brands are wary of online channels – for an online portal, a product is a product (that is, it will not differentiate between black shoes of two different brands) and it will discount it despite the brand proposition. However, brands do use online channels for liquidating inventory. These two reasons put together conspire to create a small range for online stores by any brand. Therefore, there is no direct competition yet in merchandise as far as apparel is concerned.

The entire retailing space is rapidly changing and businesses will reinvent and new models will emerge challenging even the existing disrupters. From the existing bunch of ecommerce players, structurally sound and lean business models will thrive. Third-party retailers have the opportunity to revolutionise their businesses and become relevant online marketplaces for the brands. India could see a brand-based market place akin to Tmall, with strong logistics and technology support — this could help Indian brands grow. A brand such as Bata, with a large physical store network of over 1,400 stores, is conceptually well suited for such an omni-channel enterprise and maybe the Tata group’s ecommerce initiative (with Trent and Titan playing vital roles) could very well be a rewarding offering for its participants as against the current winner takes it all charade.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access