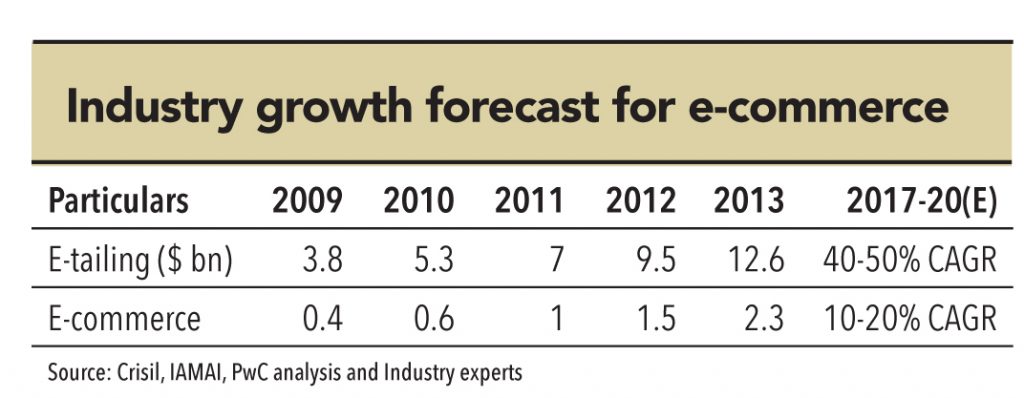

Online retailing or ecommerce is catching fire in India — while it is less than 1% of overall Indian retail, it is already 10% of organized retail and many predict it will be 8% of the total retail market by 2020!! Chinese online ecommerce giant Alibaba’s success seems to have spurred Indian ecommerce players. As the competition hots up, we take a good look at the Indian ecommerce market, its leading players, and their business models including the viability of what all of us love — discounts. We try to understand if Alibaba’s business model may have lessons for Indian retailers. We came across uncanny similarities between offline and online retailers, despite their many differences. The fundamentals of doing business online are not radically different from offline and the laws of economics will catch up with the former as well. With many offline retailers looking to bridge the ‘online’ gap, we looked at the viability of an omni-channel strategy, deployed successfully in developed countries. The competition to offline is real and business models will have to evolve — it will be an ominous threat to those who are oblivious. The online retailers’ products may be delivered in a day, but a winner will not emerge so quickly — out of the rollercoaster ride of discounts, mega sales, and promotions may emerge a business model that is unique to India, just as Alibaba’s is unique to China.

The words ‘retail therapy’ or ‘going shopping’ were long associated with physical, brick-and-mortar retail. But with stores and brands going clicky (websites) and appy (mobile apps) these terms have already widened to accommodate online shopping. Over the last couple of years, the Indian ecommerce space has filled up with home-grown players such as Flipkart, Snapdeal, and the big daddy of ecommerce, Amazon. Online shopping has captured the imagination and attention of consumers, media, brick-and-mortar players, brands, and of late, even the tax authorities and the government.

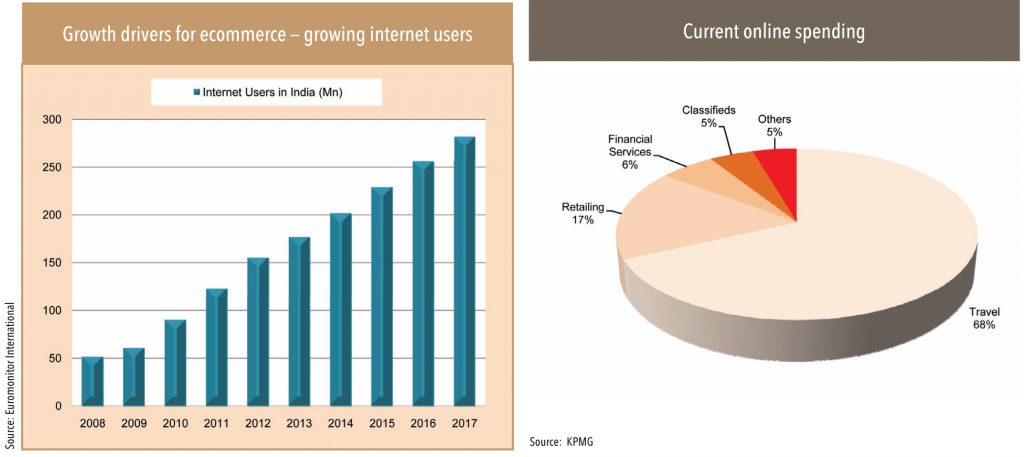

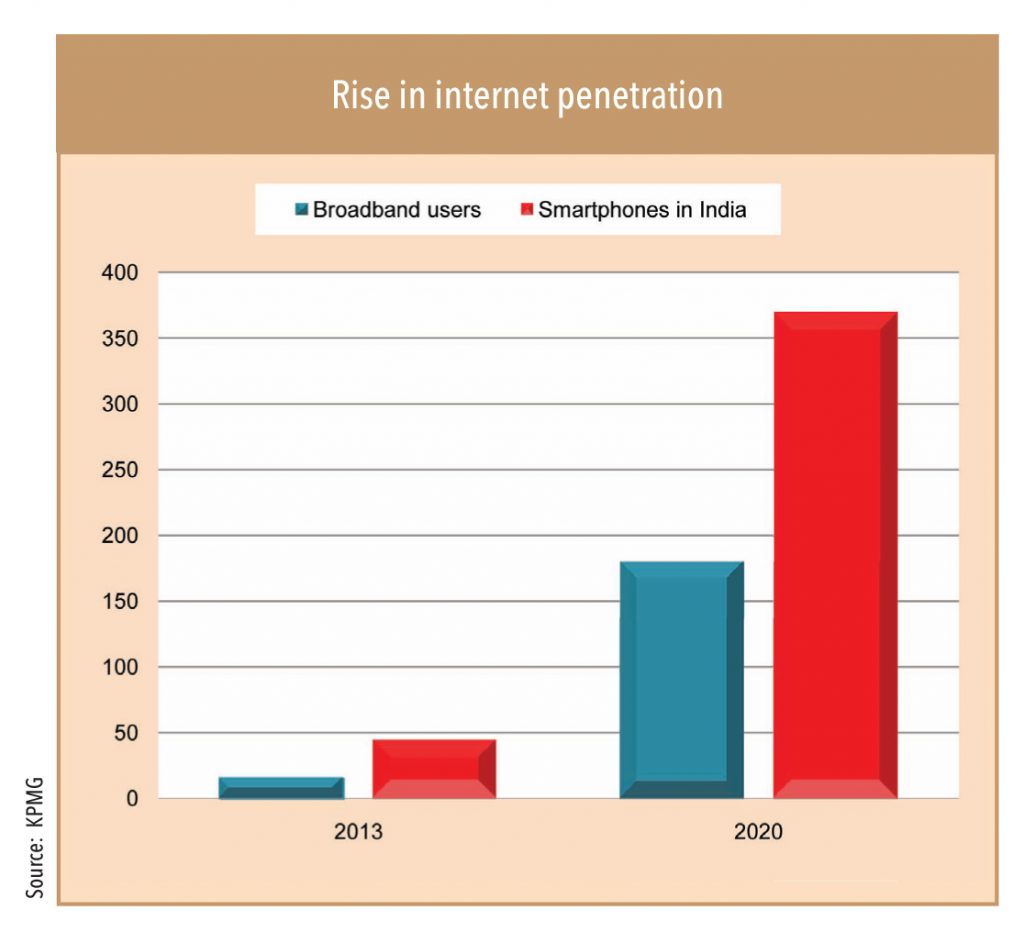

Various studies estimate Indian ecommerce to be about US$ 3bn as of now, which is just 0.8% of the Indian retail market. However, this share is expected to increase rapidly as more people shop online. Of the 200mn people in India who access the internet, 28-30mn (less than 3% of India’s population) shop online. However, this number can move up to touch 100mn by 2015 and a whopping 200mn by 2017, which is the same as the number of Indian internet users in India today. Nitin Bawankule, Director, Google India Ecommerce,says that, “Even now, there are at least 200mn people who can purchase online in India”. The market is redefining itself rapidly as etailers advertise, reach out, and offer deals and discounts to consumers.

An interesting example of increasing online shopping is the Great Online Shopping Festival (GOSF) hosted by Google. During GOSF 2013 (held over three days in December 2013), over 60mn people visited online shopping sites and 16mn unique customers shopped at the event. Myntra.com claimed that it made over 100,000 shipments for orders placed in those three days.

The average Indian online buyer is between the ages of 25 and 30 and ‘affluent’ — he/she has access to websites seamlessly through personal computers and smart phones. Interestingly, the share of tier-2 and tier-3 cities is higher for most online players. Snapdeal claims that over 60% of the orders to its website are from tier-2 and tier-3 cities. Even in the case of pure-play apparel players such as Jabong, these statistics hold true — 62% of Jabong’s shipments in Q2FY14 were to tier-2 and tier-3 markets. This demand is driven by the fact that many of the brands have limited presence in tier-2 and tier-3 markets due to shortage of quality retail space or unviable economics, given limited population in a location.

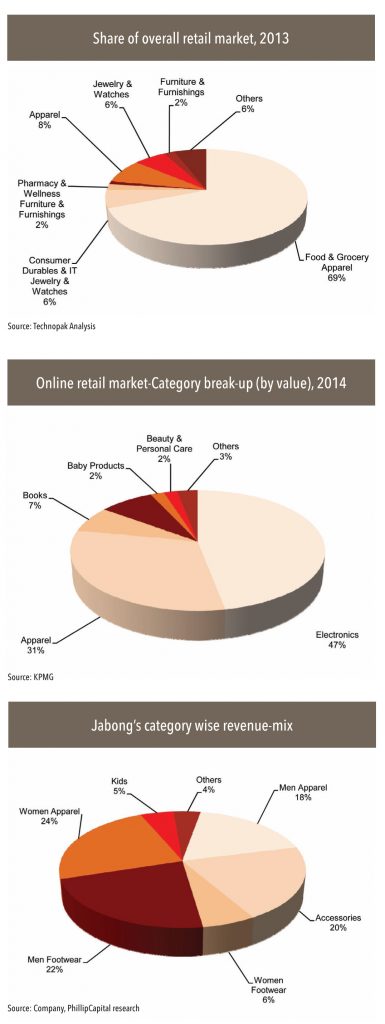

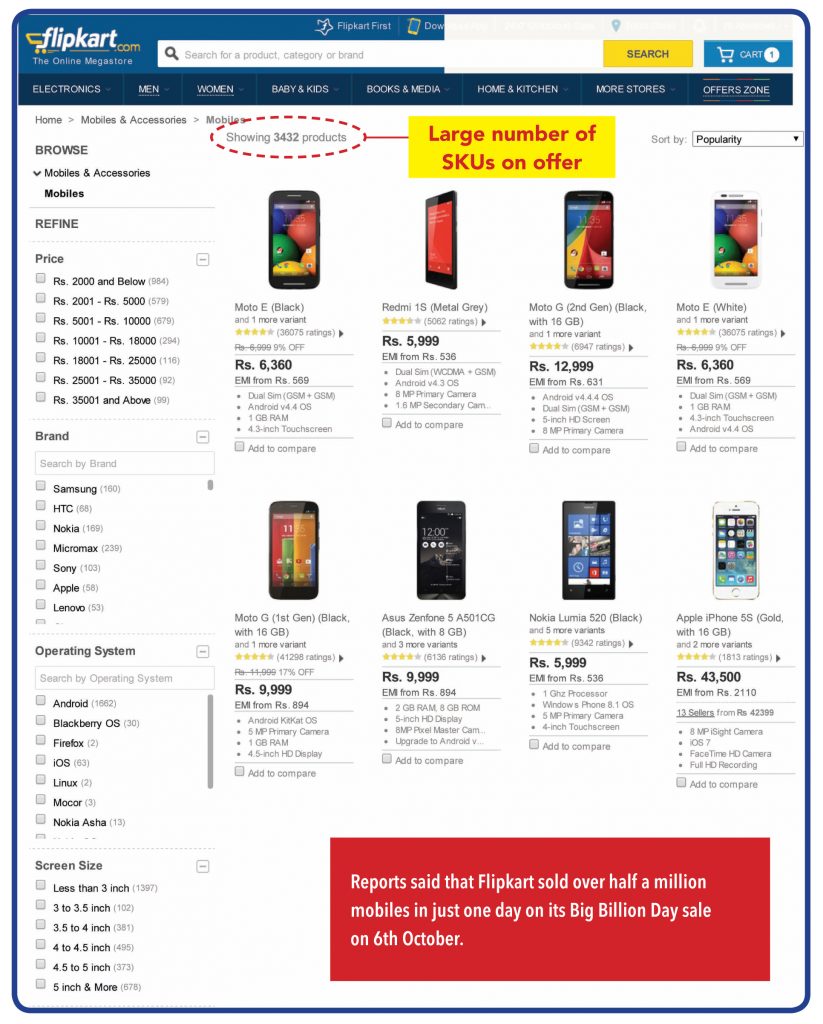

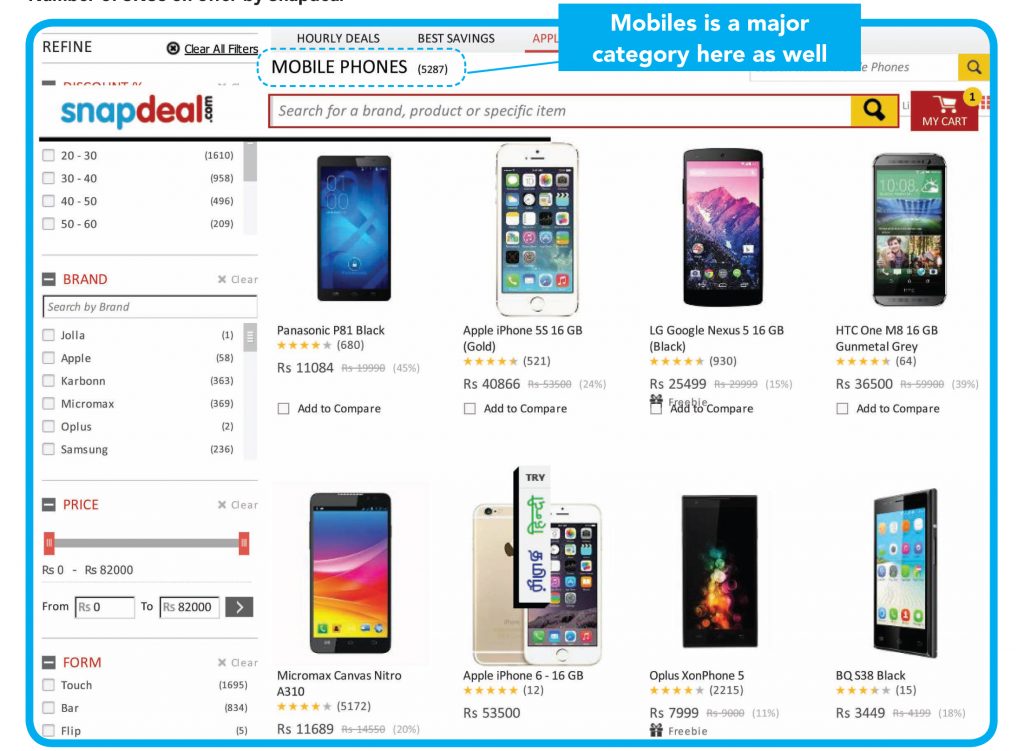

Electronics and CDIT (consumer durables information technology) products dominate the current online buying space. In terms of value, electronics is the largest category — it has a 47% share of the online retail market. Within electronics, mobile phones, laptops, tablets, and cameras are big purchases. A large logistics company that partners with ecommerce players for deliveries said that electronics (and particularly mobiles) form a very large share of their deliveries. Reports said that Flipkart sold over half a million mobiles in just one day on its Big Billion Day sale on 6th October. Flipkart and Snapdeal list over 3,000 stock-keeping units (SKUs) and 5,000 SKUs of mobiles respectively on their portals. The average ticket size in electronics is estimated to be Rs 5,000.

Apparels, footwear, and accessories are the next largest categories bought online, with a 31% share. While this category has a lower share (in value terms) than electronics, it clocks the highest volume amongst all categories. The average ticket size in this segment is around Rs 2,000. The rest of the online pie is fragmented between books, home furnishing, baby products and others.

sdf

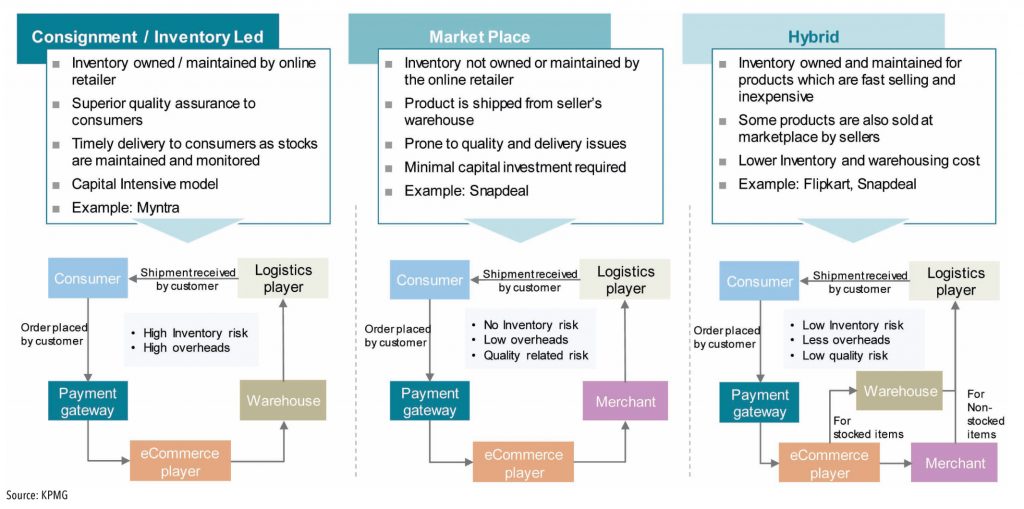

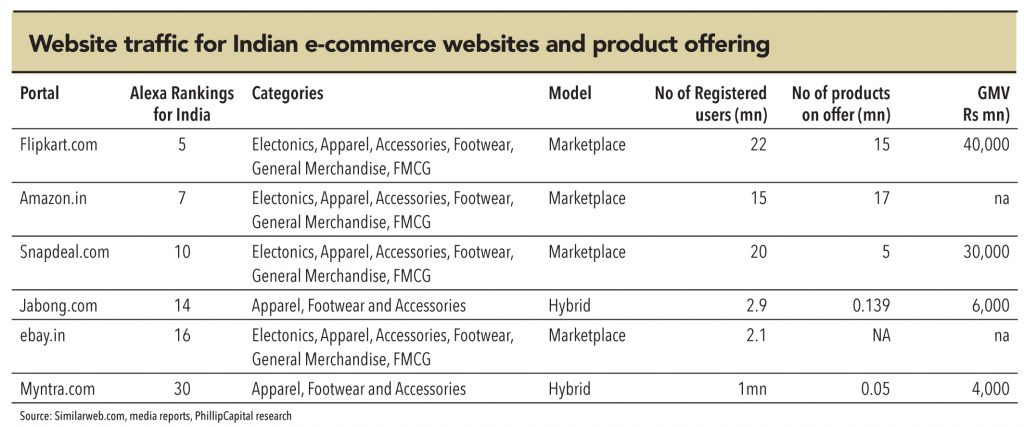

India’s online market comprises of various players with different models. Players that retail pretty much everything from electronics to FMCG products follow a version of the ‘marketplace’ model. Amazon and Snapdeal operate on this kind of a model where their role is to facilitate the sale and fulfil it — that is handle logistics, deliveries, and returns. In this model,the portals do not hold any inventory on their books. Flipkart used to operate on a hybrid model, where it held its own inventory and also acted as a marketplace. However, it has now moved to a marketplace model, albeit with far lower sellers/vendors than Amazon or Snapdeal, since WS Retail (erstwhile Flipkart group company) still contributes a significant portion of its sales. Vendors and sellers usually sign up with these marketplace online retailers for a fee, depending on the category.

Players such as Myntra and Jabong, which are primarily apparel portals, have an inventory model. They have moved to a hybrid market place, but it is still skewed towards the inventory-led model.

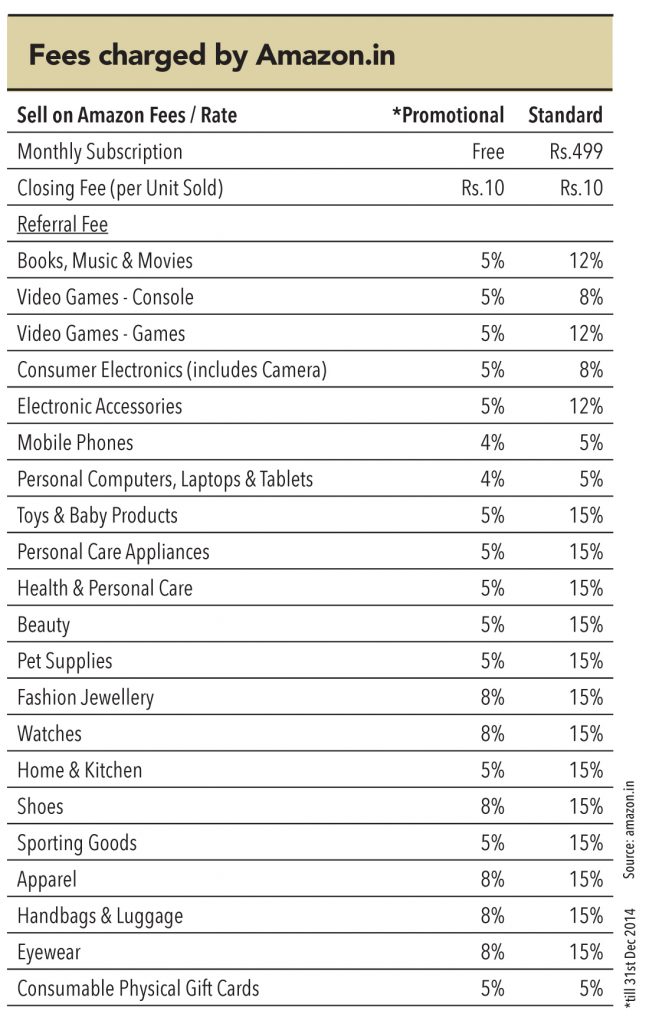

The marketplace etailers in India operate on a commission-based model, under which they receive a fee for listing plus commission on sales depending on the category. Amazon calls it referral fee. The fee is charged when an order is placed and the amount is disbursed a few days after shipping.

“These portals are not retailers but technology companies and are built on sound technology platforms,” says a senior executive of one of India’s largest retail chains. “Being pure technology companies,their platforms are well integrated with their back-end”. he adds.

Commissions are usually a function of Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) — the value of goods listed (note inventory is not carried by the companies) and sold on these portals. In a hybrid model, the revenues are more conventional as far as the e-tailers own inventory goes.

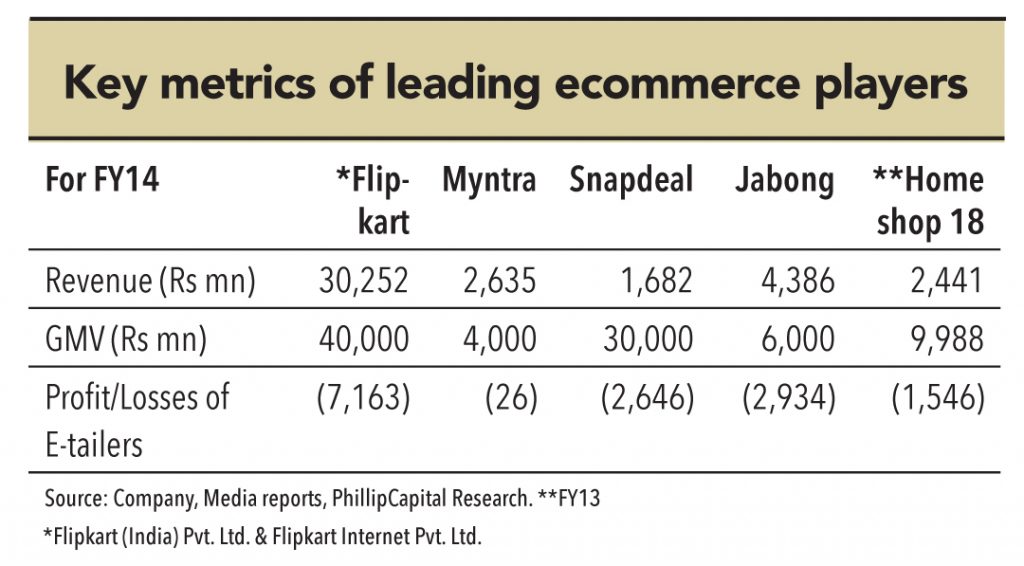

GMV is one of the benchmarks that retailers use for equity funding. But the GMV is seldom reflected in their books of accounts due to either the holding structure (complicated in the case of Flipkart and Myntra) or because revenue recognised is purely commission based (Snapdeal). However, numbers do talk and the numbers of some of the players talk more and give us an interesting insight into the operations of the sector.

GMV – Grossly misstated value?

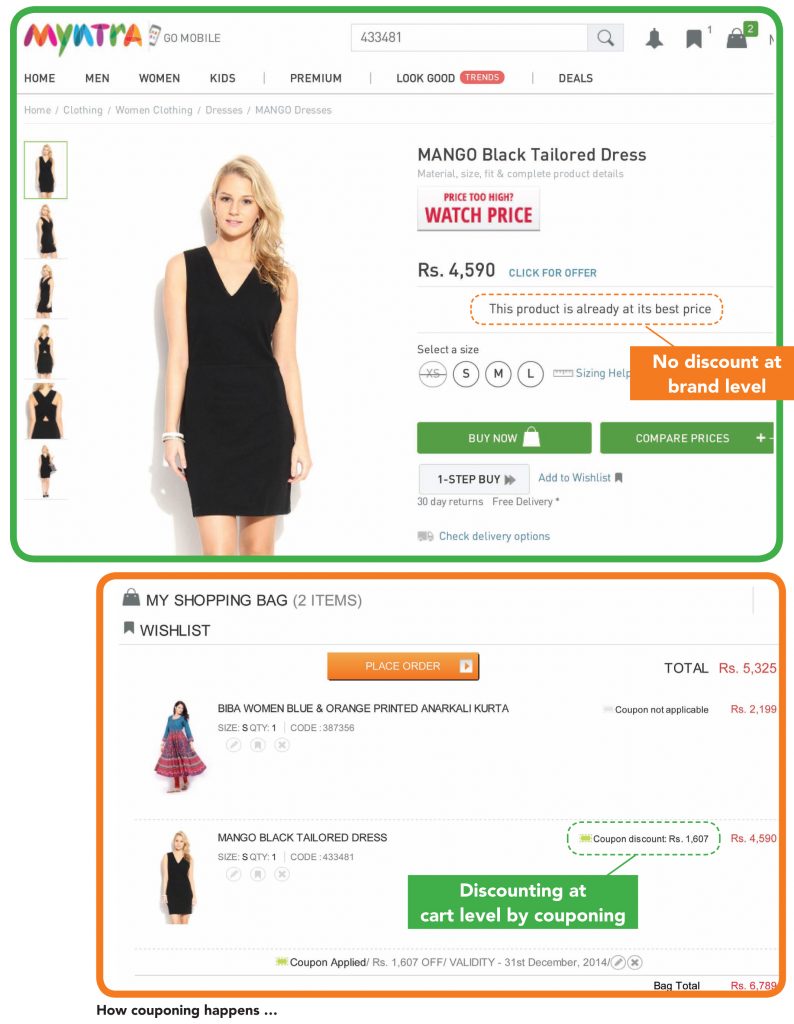

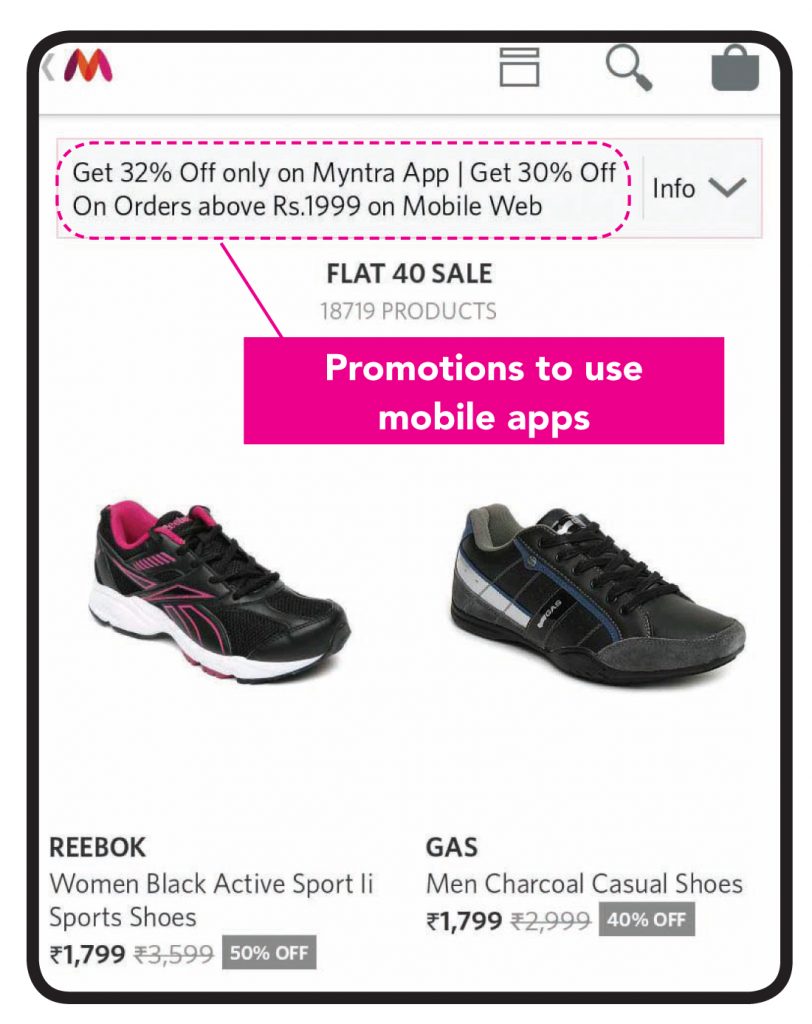

GMV is before all discounts, couponing, vouchers, and taxes. So when we read about a GMV of US$ 100mn in a day or US$ 1bn, it is the gross value of products before discounting and couponing. But what the customer pays is net of all discounts, vouchers, and coupons. GMV is open to interpretation and different retailers may compute it differently.India, unlike many developed countries, follows a maximum retail price (MRP) regime for sale of goods. Discounts are offered on MRPs. But then, one company may choose to compute GMV on MRP while another may compute GMV on the list price (MRP minus discounts that the brands/seller offers). While MRP is relevant in most consumer products sold anywhere in the country, it’s the least relevant in electronics. When was the last time anyone sold a mobile or a television or home appliance at MRP? Since electronics form nearly 50% of the e-tail in India, it is natural that the GMV calculated on MRP will be skewed. GMV is reported on the current run rate rather than the achieved figure. So GMVs for Flipkart and Snapdeal could be misleading given the high mix of electronics.In e-tail shopping, there is almost always a coupon – a coupon or a voucher code is essentially a discount over and above the listed price, which may or may not be discounted. These are at the discretion of the e-tailer and not under the control of the brand. It’s more commonly used by apparel e-tailers such as Jabong and Myntra. It’s noteworthy that Flipkart and Amazon seldom use couponing. One of the industry observers said that, “Coupons are a mechanism of customer acquisition and in apparels, the customer doesn’t necessarily visit the website very frequently, and to get him/her to do this, coupons are offered regularly.”

Marketplaces such as Flipkart and Amazon, catering to a large variety of products, rarely offer coupons as the customer ends up visiting the site for some category or the other. Apparels/fashion have the maximum margin. Interestingly, GMV includes the value of vouchers/coupons as well, which means it is calculated before any coupons are offered to the customer. As one of India’s largest retailers puts it, “If it were net of any of these discounts then it should be called net merchandising value not GMV.”

Couponing between rival portals is continuous. An offline retailers said, “If you don’t want a good price, we will still offer you a coupon.” What this means is that even if a product is displayed on full price, the customer is still offered a discount coupon when he checks out his purchases (just before the payment stage).

Show me the money

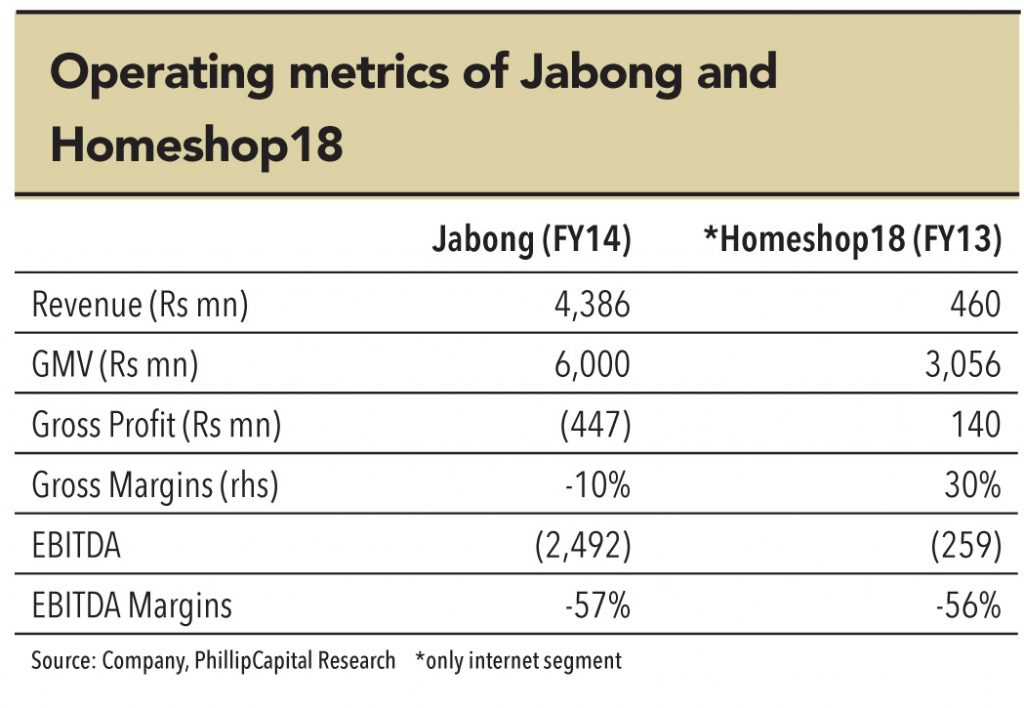

The underlying revenue model of most of the entities that operate e-tailing portals are commissions and gross profits — if they also follow the hybrid model. But the costs of e-tailing are intriguing and they cause of a lot of heartburn to offline retailers as well as brands. Contrary to perception that online retail entails lower costs as there are no costs associated with operating stores, these businesses have high costs in the form of discounts, free delivery for products (where cost of the product is sometimes lower than delivery costs), and customer returns. In e-tailing parlance, some of these costs are known as ‘customer acquisition costs’.

Customer acquisitions cost: In-fact, the largest cost for e-tailers in a nascent ecommerce market such as India is customer acquisition costs — this is because it includes discounts offered on owned merchandise or the cost of funding discounts in a marketplace model. These discounts are offered over and above the discounts offered by brands or sellers of the product and are usually offered to customers in the form of coupons. They are known as cart discounts because they can be availed once the customer adds the product to his or her cart. The discounts sometimes tantamount to losses at the gross level (transaction level) in the hybrid model; in a marketplace model, they sometimes exceed the commissions that the e-tailer earns. E-tailers bear these losses for customer acquisition. However, these discounts are not limited to a one-time purchase and are often open for all — they don’t distinguish between old and new customers. This implies that they are given not only for customer acquisition but also for customer retention. Of course, there are cases where coupons are offered for registering on the portal. Clearly, the e-tailers’ losses are the customer’s gains.

“The Prime Minister says ‘make in India’ ….but given the recent funding the e-tailers have received, one would imagine it’s the best time to Buy in India. It’s a direct benefit transfer – from shareholder to customers,”says a senior executive of one of India’s largest retail chains.

Discounting is the key driver to buy today. A consumer will buy standardised products for convenience but the first greed is price. Mr Biyani of Future Group explains, “Anything which sells in a matter of seconds is usually a product where the price is lower than the perceived value. For example a Xiaomi mobile (which usually gets sold out in seconds).”

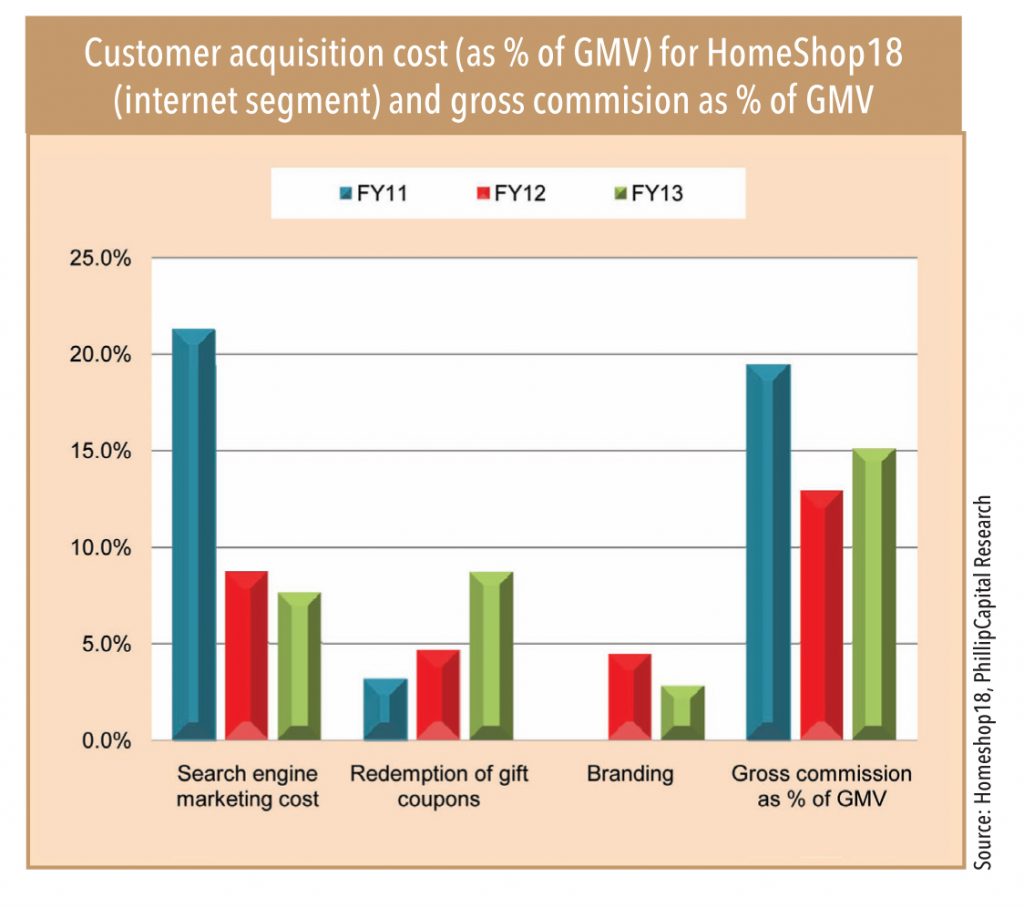

But customer acquisition costs don’t end here. The other significant costs are Search Engine Marketing (SEM) costs. These are costs that ecommerce players incur to direct traffic to their portals on leading search engines such as Google. Typically, searches for key words associated with the merchandise on offer on a portal will direct the traffic to the portal. For e.g., if one searches for ‘buy shoes’ online, the search results will throw up names of portals that sell shoes and to ensure that the e-tailer’s name appears in the top-5 search results, or in the first page of search results, these portals incur search engine marketing costs.

One of the most interesting cases of SEM costs is when flipkart.com ran its big billion day sale on 6th October 2014. When one searched for “big billion day” on Google the search actually led to amazon.in instead of Flipkart!! – it seems like Amazon paid Google to direct the search to their website.

Logistics costs

One of the peculiarities of the Indian ecommerce market is the high share of cash on delivery (CoD) orders. Unlike most other countries, the share of prepaid orders is very low in India for many reasons. Most buyers either don’t have a credit card or net banking (not really surprising for a country where more than 40% of the population doesn’t have bank accounts). More than 50% of the orders that are placed on Indian ecommerce websites are CoD orders says Mr Bawankule of Google India. CoD has inherent problems — it allows customers to change their mind after their purchase has been shipped and sometimes couriers have to wait for customers to make a payment, which in some cases may not happen quickly for want of ready cash. Homeshop18’s return rate for COD and non-COD transactions was approximately 21.4% and 2.8% in FY13, respectively. A logistics company executive states that there are instances when the customer doesn’t have ready cash at home and the courier has to wait till he withdraws cash and returns home for collecting the payment.

Adding to this complication is the reach of logistics companies to various parts of the country. A KPMG report estimates that most logistics companies service around 6,000 area pin codes out of the 22,000 area pin codes in India (less than 30%). To overcome this problem of reach, some online players such as Flipkart and Amazon have established their own logistics team alongside using third-party logistics companies. However, the rationale for establishing their own logistics network is not reach alone — an executive with a leading logistics player said that CoD deliveries (by third party logistics vendors) cost more because they are more time consuming and need checks and balances (given the cash handling). Some of the checks and balances include mid-day reconciliation and deposit of cash collected. Therefore,the logistics companies are unable to make optimum number of deliveries and this cost is billed into the CoD orders. Moreover, air shipments (more expensive) still constitute over 80% of the total shipments.

This does make one wonder if operating your own logistics is viable? The logistics executive’s view on the matter is, “Actually own logistics is not profitable as there is a fixed cost involved and it is seldom able to make optimum orders given the complications of CoD. Our operations are tuned to make deliveries across a designated area irrespective of who the shipper is, hence our efficiencies will be high. The fundamental reason why ecommerce players get into their own delivery logistics apart from handling COD orders is working capital requirements. Logistics companies can take anywhere between 5 days to 15 days to remit the cash collected on delivery to the ecommerce players and that robs them of working capital.” Given that most ecommerce companies are operating on losses, working capital management becomes imperative. Mr Basrur, Head eCommerce at Raymond Ltd (also one of the founding members of Quikr.com – a classifieds website) observes, “In-house logistics capabilities of ecommerce players are not going to be too different from those of third-party vendors. It’s a function of where the product is (known as fulfilment centre) and where the customer is. However, costs still may not be justified for own logistics as number of deliveries made are likely to be sub-optimum.”

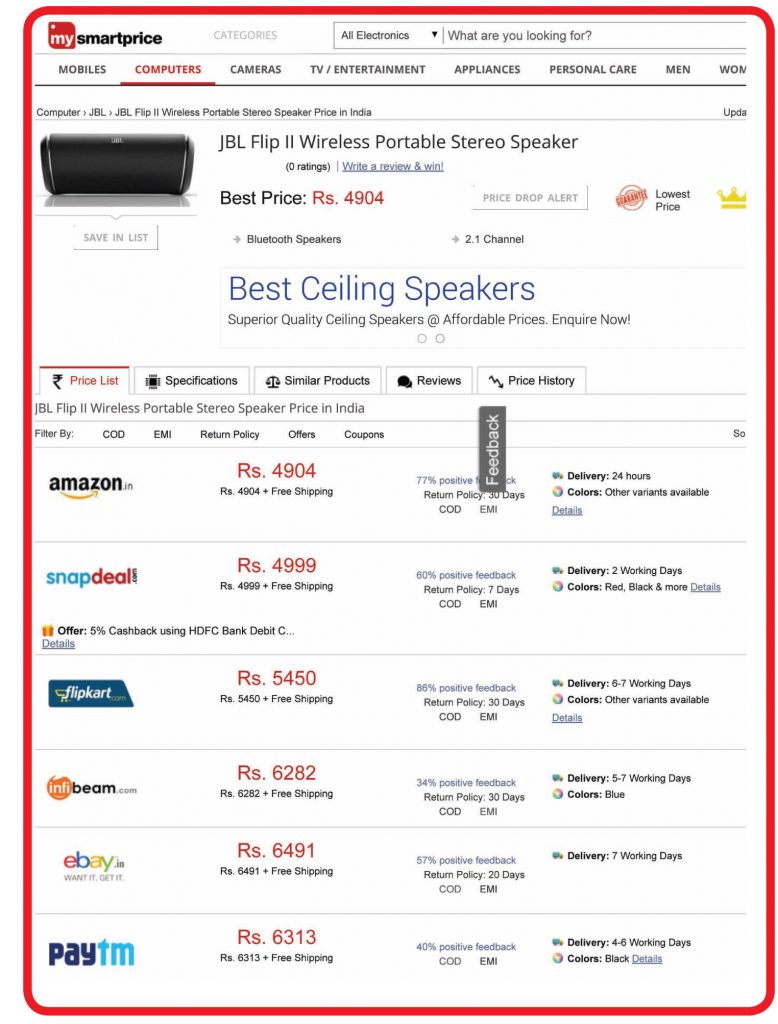

Discounts, free delivery, cash on delivery, easy returns — who wouldn’t want to be an online consumer.But one of the main reasons why consumers continue to flock online is the range of products and the convenience of not having to step out of your home and buying everything under one roof, says Mr Bawankule of Google. While for a consumer in developed markets convenience and range are most important, for the Indian consumer it’s price and range. Online stores, especially marketplaces, literally bring the store to the consumers’ desktop or mobile. The variety and categories on offer at a click or touch are unparalleled. And to top it all, there are apps and websites which guide you on best pricing of the product. Ever tried mysmartprice.com? The website actually aggregates the best prices of the product and sorts the websites retailing the products in ascending order of prices.

Indian e-commerce is rapidly evolving as consumers embrace technology and lap up products available online. While consumers would continue to benefit, offline players seem to have been caught off-guard in most categories. Like any new development, e-commerce has disrupted the market and many players have branded it as an agent of chaos that is unlikely to ever make money and will be one whose ship will sink.

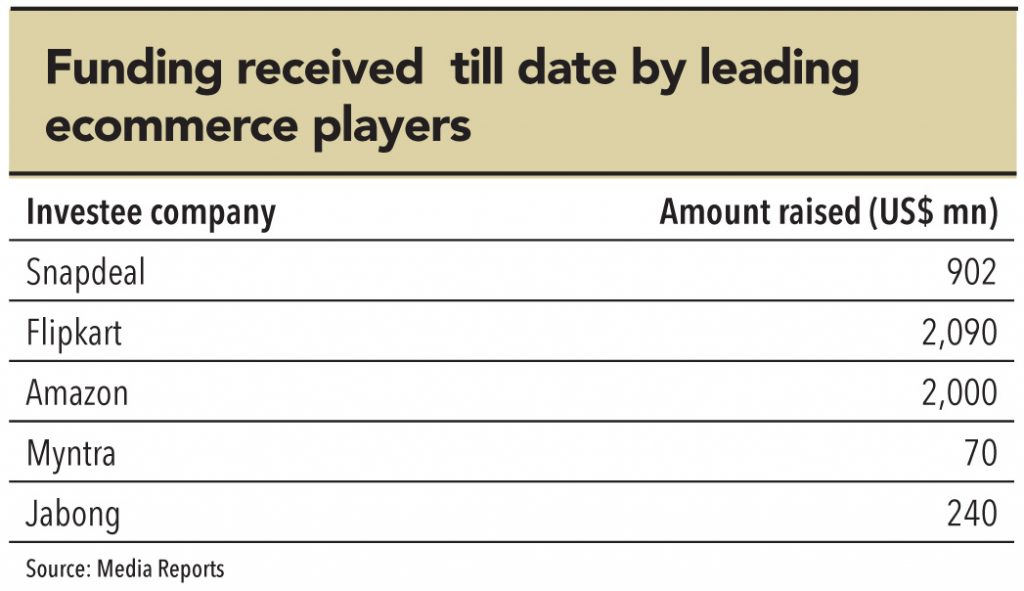

Since March 2014, nearly US$ 4bn of private equity money has been invested in just 3 players – Flipkart, Amazon and Snapdeal. Even if half of it finds its way to customers in the form of discounts, there could be another US$ 5-8bn of discounted sales coming the customers’ way. Therefore, offline retailers will have to gear up, adapt, and more importantly, adopt unconventional and possibly untested strategies to counter the disruption caused by ecommerce. If offline retailers do not evolve, they might as well be writing their own obituary.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access