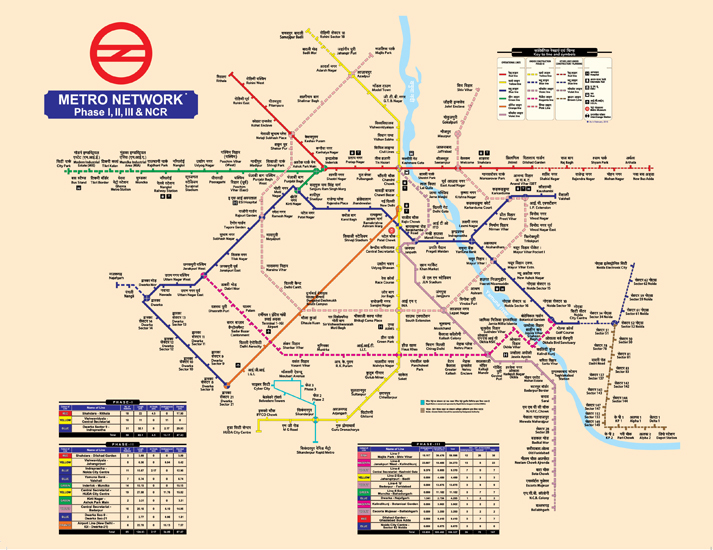

Delhi Metro network, built and operated by the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation (DMRC), has inspired various government bodies (centre and state) to implement metro projects across the country. The network, which started from a single line of 8km and six stations, has now expanded to 190kms and 143 stations – and is still expanding. It is now the 12th largest metro system in the world – both in terms of length and number of stations.

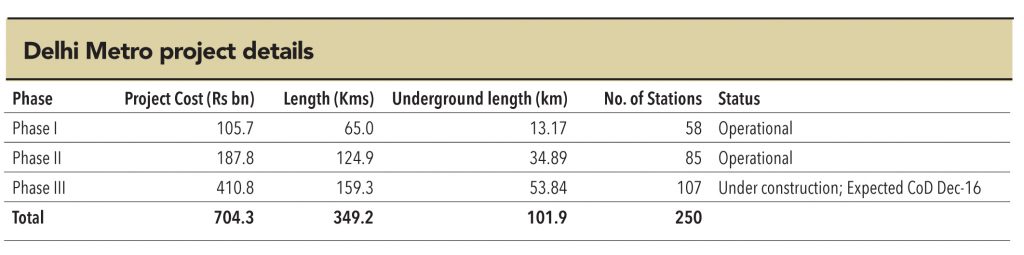

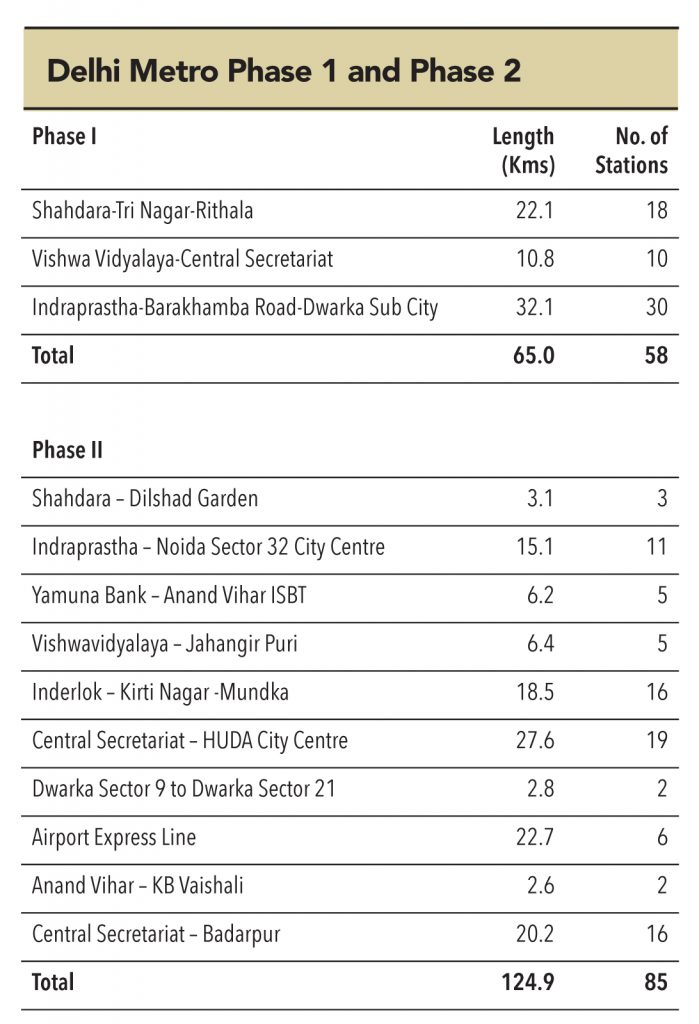

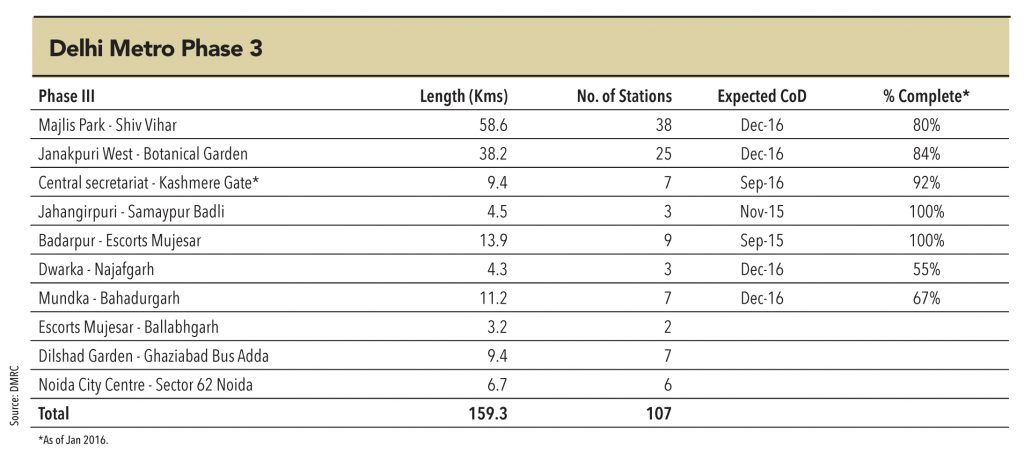

Currently Phase 1 and 2 of the DMRC development plan are operational, boasting of a daily ridership of 2.4mn passengers. Phase 3 of the network (160km, 107 stations) is currently under construction, which will expand the connectivity of Delhi to Greater Noida, Ghaziabad, Badarpur, Najafgarh, and Gurgaon – and is expected to take the annual ridership to 4mn passengers.

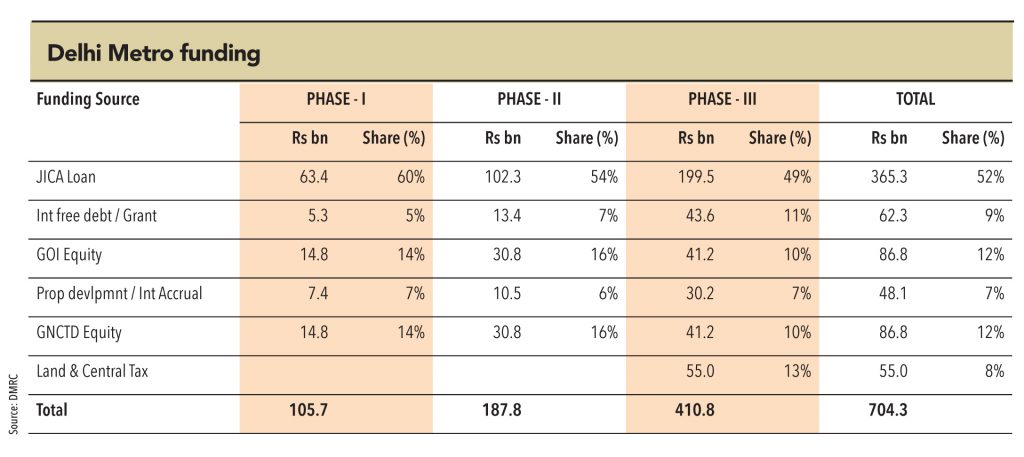

DMRC has already spent Rs 290bn on the first two phases of the Delhi Metro network – funded over 50% by JICA. Phase 3 entails an investment of Rs 411bn, which will again be 49% funded by JICA.

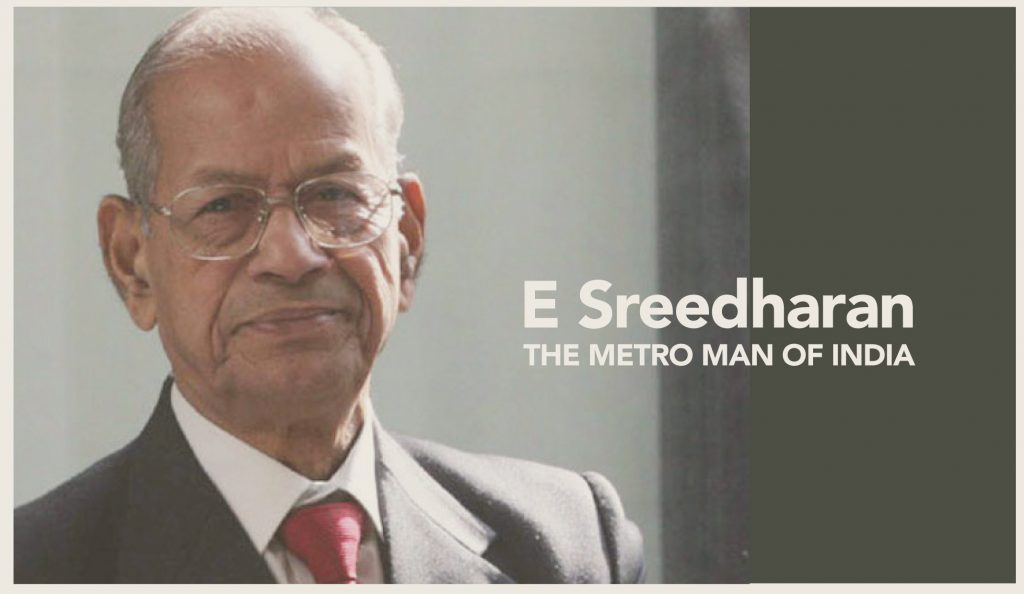

Delhi metro has been exemplary in more ways than one. It showed the Indian public and bureaucrats that government projects could be executed in a timely and cost-effective manner. It was admirable – the way in which its MD over 1995-2012, Dr E. Sreedharan (the man credited with turning the metro dream of the country into reality), executed the project ensuring minimum inconvenience to the public (“some inconvenience will be there”, he once quipped).

DMRC also deployed multiple engineering techniques for the first time in the country. In the early stages of the project, it used the ‘incremental launching method’ to speed-up the construction of a 533-meter span-bridge over the river Yamuna. In 2002, when the Delhi metro was expanding to the northern part of the city, it experienced severe difficulty in boring underneath the ground due to the unpredictable nature of the soil. Every day of delay was costing DMRC Rs 130mn. To overcome this, it deployed NATM – New Austrian Tunnelling Method – for the first time in India. Hard rock was blasted using explosives and TBMs (Tunnel Boring Machines)

were thereafter used to excavate and complete the construction work. The result is the Chawri Bazaar Station – at 30-metres below the ground – one of the deepest metro stations in the world.

Phase 3 is the largest and the most ambitious phase planned by the DMRC. Currently, only two lines of 18kms are operational, while work on all other corridors (apart from three lines) will be complete by December 2016, which will add 159kms and 107 stations to the Delhi metro network.

The contribution of the Delhi Metro to economic activity has been huge. But what has been even more remarkable is its impact on the development of the NCR region – the suburbs of Noida, Gurgaon, and Faridabad. Seamless connectivity to almost every part of the city has ensured that a large number of potential migrants from these regions can now stay back in their native places and travel to work every day. This has also led to an increase in job opportunities for people in the neighbouring poor states of Haryana, Rajasthan, and UP.

Financials

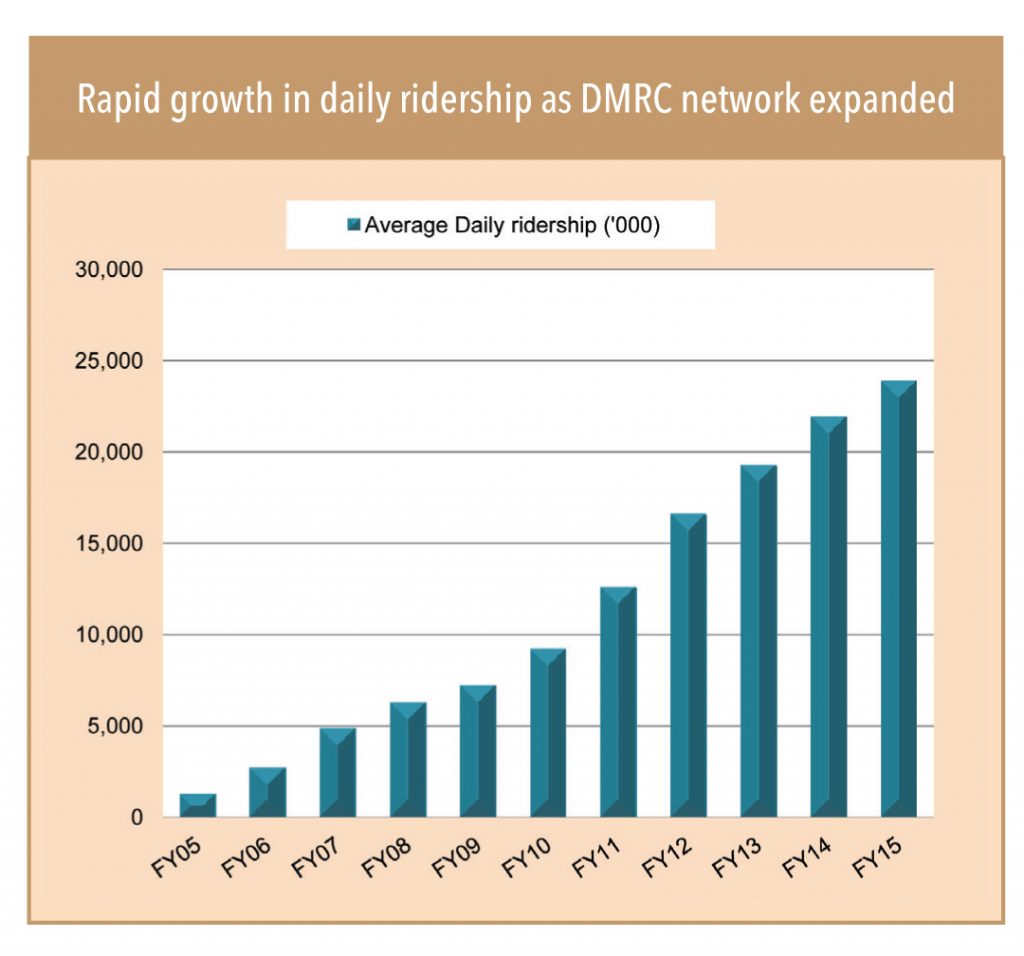

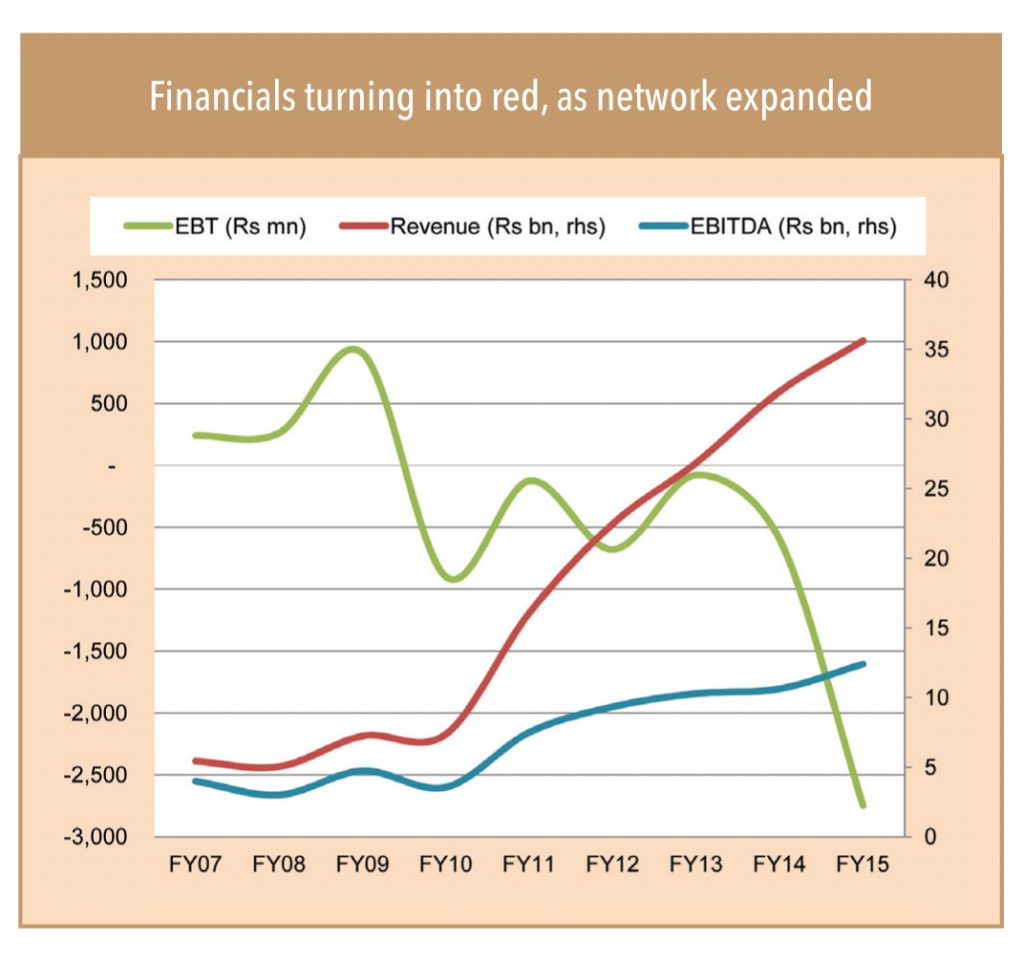

The Delhi Metro’s success lies in its reach and the steady rise in its ridership. Its average daily ridership has grown to 2.4mn in FY15 from 124,000 in FY05 – as the network expanded from its initial 15km to touch 294km now. The annual revenue for DMRC has also increased – to Rs 35.6bn in FY15 from Rs5.4bn in FY07. However, continuous capex and expanding network has meant the Delhi Metro, which was once profitable (along with HK Metro) has slipped into the red – its net profit of Rs 240mn in FY07 has turned into a recent net loss of Rs 2.75bn.

Yet another first in the country

Soon, DMRC will embark upon yet another revolutionary journey – it plans to operate driver-less trains, for the first time in India, on sections of the Phase-3 network. The new trains, which will begin service with drivers for a short period, are expected to be operational by the end of next year. For unattended operation, stringent trials will be held (global standards – 12-18 months trial period).

The trains will run on the over 58 km-long Majlish Park-Shiv Vihar (Line 7) and the 38 km-long Janakpuri (West)- Botanical Garden (Line 8) corridors of the Phase-3 – both expected to be operational by Dec-16. The trains will have on-board CCTV cameras for inside and outside view of the train, which would be directly accessed by the control centre in driverless mode.

“These new-generation trains are suitable to eventually run on UTO mode, that is, train operators will not be required to operate these trains and the Operations Control Centres (OCC) of the Delhi Metro system will directly regulate the movement of the trains,” DMRC official (media source).

“Even the rich people will also use metro after about 10 years, when they find that there is no place to park their cars”

-Dr E.Sreedharan, on the use of metro networks by different sections of society.

NO report on the metro network in India can be complete without mentioning the Metro Man as he has popularly come to be called – Mr E Sreedharan. He is the person to credit with taking Delhi (and the entire country) into the 21st century on the wheels of the metro networks – he served as the Managing Director of DMRC from 1995-2012. He was awarded the Padma Shri in 2001 and named one of Asia’s Heros by TIME magazine in 2003.

Mr E Sreedharan joined the IES (Indian Engineering Services) in 1954. Due to his excellent work and skills demonstrated during his tenure, the Indian Railways called him back to head the Konkan Railway project even after his retirement in 1990. In this, he completed one of the most beautiful and breathtaking stretches for the Indian Railways – a track of 760km on India’s west coast with 150 bridges and 92 tunnels – and all this with no cost/time overruns! This paved the way for an assignment that was to transform his legacy – he headed the DMRC.

It was E Sreedharan’s dedication that helped secure Japanese funding for DMRC and many other metro projects thereafter. Sceptical of Indian engineers executing a metro project on time and within the estimated cost, Japanese investors were shy of investing. Sreedharan and his team set out to convince them in the best manner that engineers know – by building things. They constructed the first 8.5km stretch of the Delhi metro within the stipulated four years (an unheard of schedule until then). The stretch had many challenges – the biggest was constructing a 533-meter span-bridge over river Yamuna, which itself was going to take two years. Sreedharan’s team used ‘incremental launching method’ for the first time in India and completed the project on time, securing Japanese funding.

Sreedharan’s extremely high energy was contagious – this spurred contractors, both domestic and foreign. Sreedharan was an exceptional engineer, had keen business acumen, and shared a good rapport with staff. He made land acquisition into an art – he even sent movers and packers to facilitate people vacating their premises. At one point, he convinced the school management to provide him with the land and necessary support to construct the metro station right next to their premises by bringing them on board about how the children would actually benefit due to the station. His corporate consciousness meant he retained most of his key staff, even when the private sector lured most of the DMRC staff away with lucrative salaries. Sreedharan is credited with a lot of ‘firsts’ in the DMRC project – the ‘incremental launching method’ to build bridge over Yamuna, the ‘NATM’ for tunnelling under the unpredictable terrain underneath North Delhi, etc. However, one special thing that the DMRC staff still remember him for is his ‘reverse clock’. For every critical phase of the Delhi metro, to keep everyone on their toes, he put a huge clock that ran backwards to the deadline.If there is one man who can be credited with professionalising the way PSUs worked, of convincing foreign investors of the infrastructure potential in the country, or of taking the country into the 21st century – it has to be E. Sreedharan. And the most unbelievable part is he did all this while heading a PSU and with a monthly take-home salary of only Rs 30,000.

We build roads such that they require minimum maintenance and have NO potholes

We met Mr Chin Kian Keong, Group Director at Land Transport Authority (LTA), Singapore. LTA is in charge of the roads and metro network in the city of Singapore and works in coordination with the urban development ministry. Just like India, and most other countries, it constantly runs into the green development department and utilities department while carrying out its expansion/maintenance projects.

Few points during our interaction with LTA were eye-openers for us. For example, despite the highly efficient metro network that exists in Singapore, which is more than adequate for the city’s current needs, the LTA is already executing its next phase of expansion, which will double the existing network length (to 360km from the current 178km) – taking care of the next 20 years of the city’s transit needs.

The LTA currently employs 6000 people – a rather high number we believe, keeping in mind Singapore’s 5.5mn population. It is completely funded by the Singapore government, and had a maintenance budget of US$ 400mn last year, over and above the US$ 2bn expansion capex. The LTA makes extensive use of CCTV cameras to monitor the traffic and upgradation requirement of the metro/road network in the city – it has deployed over 1000 CCTVs across the city.

Our conversation with Mr Keong hit a rather surreal patch when we tried to find out how and when they carry out patch-repair work on their roads, especially potholes. After 3-4 ‘lost-in-translations’– we figured it was actually an unchartered territory for him. “We build roads such that they require minimum maintenance and have NO potholes,” he told us. For the miniscule number that do appear, they use pre-fabricated ‘bitumen packs’ which are dumped into the potholes, and take its shape, filling it up almost instantly!

The LTA also uses regulation in the best possible manner to benefit citizens. The tolling on various roads is done to manage traffic NOT to add to revenues. It also controls the number of taxis running across the city – giving licenses to companies and NO individuals. The companies have to adhere to multiple constraints minimum fleet size of 200 – and plans to expand to over 500 during the next two years.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access