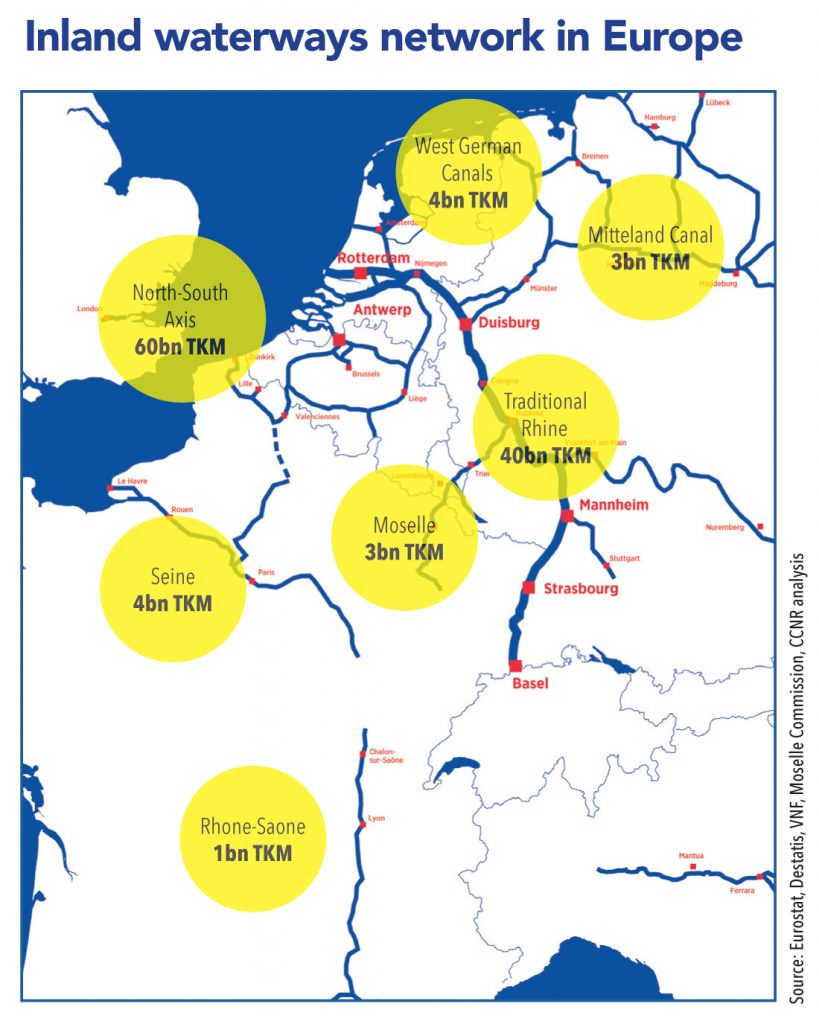

The dominance of maritime and river navigation has characterized the transport of goods for centuries. In Europe, more than 37,000km of waterways connect hundreds of cities and industrial regions. Waterways play an important role in the movement of cargo globally, with a staggering 90% of world trade moving on water. However, in India, the use of waterways for domestic movement is limited in spite of its long coastline as well as a huge network of rivers. This is all the more tragic considering India is naturally blessed with 14,500 km of navigable waterways that can be effectively used for cargo movement. The country has 13 major ports and around 185 minor ports (under state governments) spread across 9 maritime states. The share of coastal shipping in the modal mix of domestic freight transportation in India is low, at just 6% while around 93% of freight is carried over land transport. This, despite waterways being more cost effective, fuel-efficient, and environment-friendly compared with other modes of transportation. To provide perspective, India’s sea-borne traffic is just 950mn tonnes, even with a total coastline of 7,500km. China’s is almost 10x more at 9bn tonnes with a coastline that is twice India’s at 15,000 km.

However, hope floats. The government has been making a strong push for developing coastal shipping and inland waterways over the past few years, and this has started showing results. Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated India’s first multimodal terminal at Varanasi for inland waterways late 2018. On that day, this terminal received India’s first container movement on an inland waterway since Independence. Meanwhile, a ferry service for cargo and passengers (RoPAX) between both Ghogha and Dahej under the Sagarmala initiative has reduced the travel time between Saurashtra and South Gujarat to just over an hour (from 7-8 hours) and the distance is down to just 31km from 360km. Cargo movement in the northeast through NW-2 and Bangladesh protocol is also picking up.

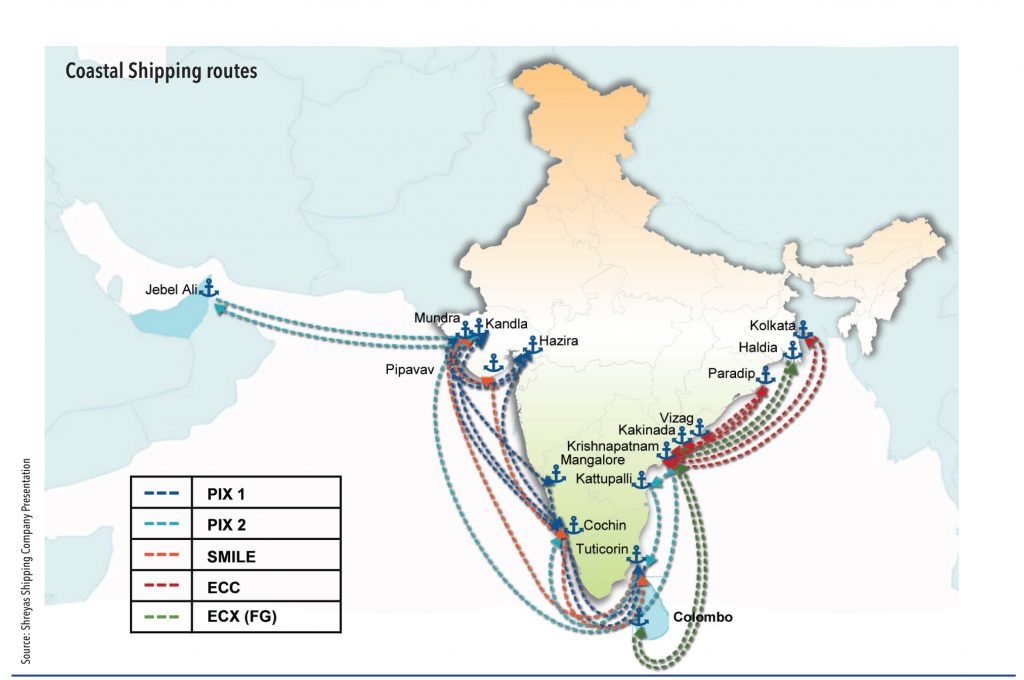

Government initiatives to promote coastal cargo – through reduction of tax on bunker (which is any fuel poured into a ship’s bunkers to power its engines), relaxation of Cabotage Law, simplification of manning requirements, and concessions on vessel-related charges at ports with priority and separate coastal berths at major ports – are expected to benefit the sector. Relaxation of cabotage rules is likely to develop transhipment opportunities for shipping players. Out of the total 17.5mn TEU container traffic in India, around 20% is transhipped; of this, about 40% volume is handled at Colombo alone. Coastal shipping and inland waterways offer huge potential in bulk transportation (125mtpa of coal transport for thermal power plants and 40-45mtpa of other commodities).

With 111 declared waterways, the scope has indeed increased and the government aims to increase the share of waterways to 12% of total cargo volume from current 6%, with cargo rising to 150mn tonnes from 70mn at present. Waterways will not only reduce the burden on roads and railways, but also boost the economy and save the environment. Though the sector offers attractive opportunities for a modal shift, last-leg connectivity remains very important and much of its success hinges on the kind of efficiency that can be brought into first- and last-leg distribution.

Neglected for many years, water transport has gathered momentum with the government’s support and improvement in port infrastructure

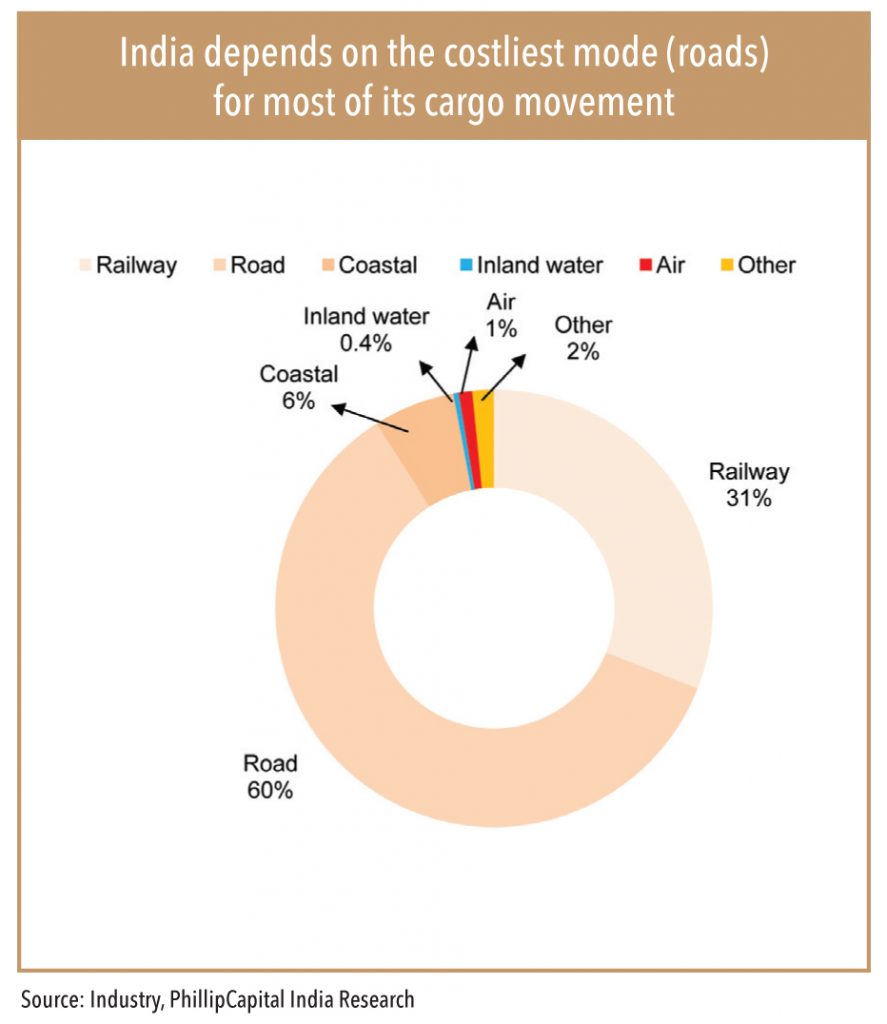

Moving cargo and passengers through waterways is cheaper than roads and railways, and more environment friendly. However, so far in India, regulatory and infrastructure related issues have not been conducive to the efficient use of waterways. The statistics are disheartening. As of 2017, the share of water transport (including coastal and inland waterways) was a little more than 6%; conversely, roads was 60% and railways was 31% (Source: Report from National Transport Development Policy Committee , 2017).

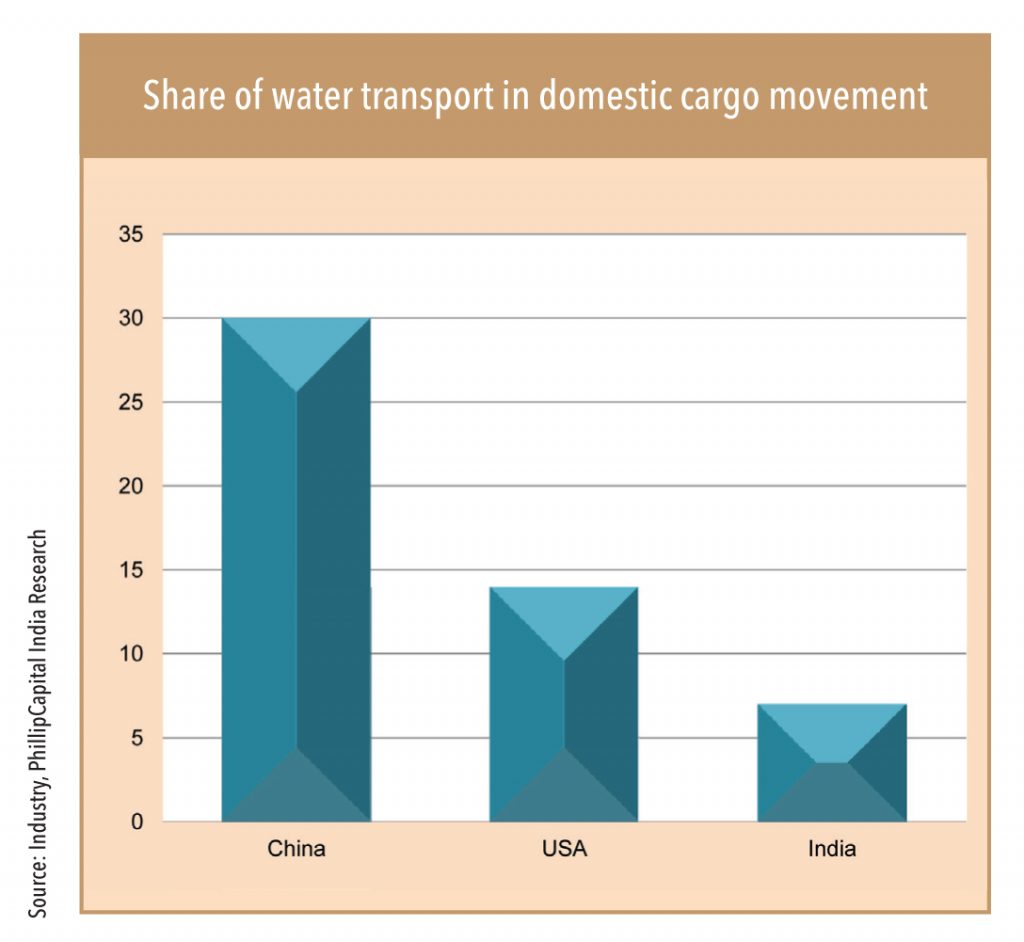

India’s planning commission wants to increase the share of low-cost transport (rail and water) to reduce the country’s overall transportation costs. Most countries have efficiently developed their waterways for cargo and passenger movement. For example, 14% of US’ domestic cargo moves through waterways; the figures are – 30% for China, 40% for Japan, and a low 7% for the EU.

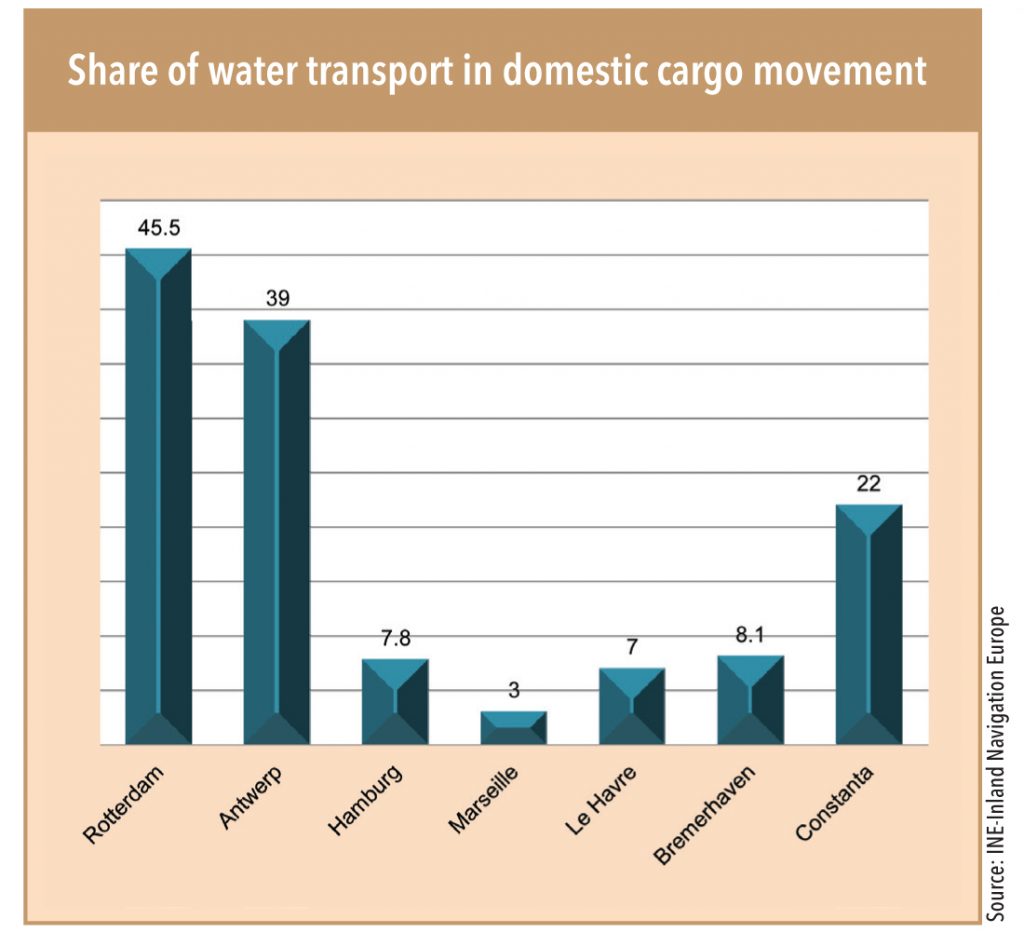

While the overall share of waterways in the European Union appears low at c.7% of freight volume (with 40,000 km of navigable waterways), it is considerably higher in individual countries with good waterway infrastructure – such as Germany at 12%, Belgium at 15%, and Netherlands at a whopping 37%. Some of Europe’s largest seaports use inland waterways because of increasing congestion. Rotterdam, for instance, avoids using almost 100,000 daily truck movements because of the use of inland waterways (Source INE – Inland Navigation Europe).

Waterways offer a powerful environment-friendly solution to road congestion

This is a government initiative to promote costal development and waterways

Key highlights

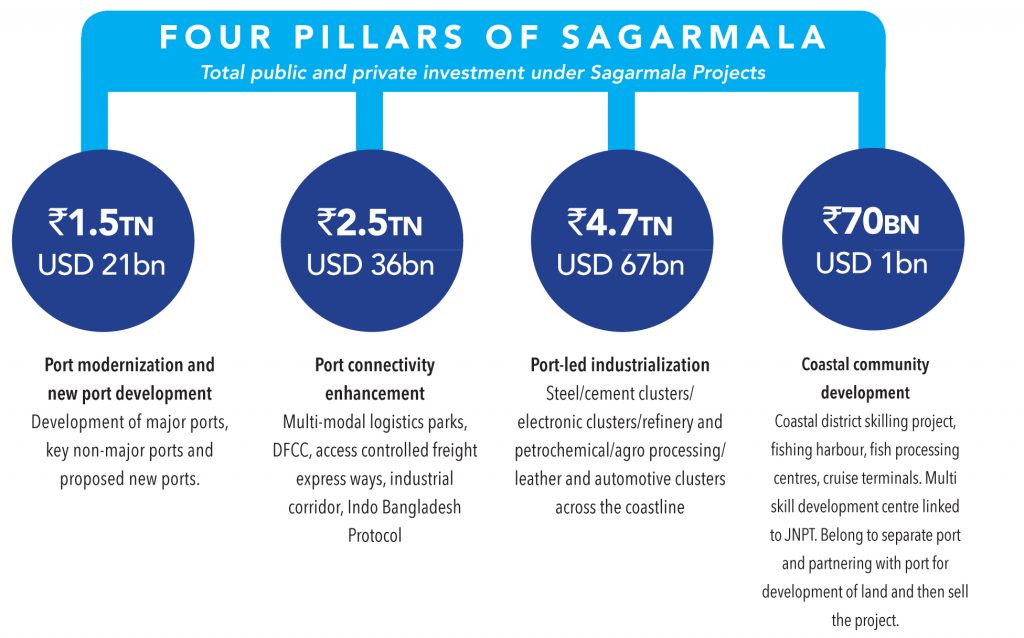

• Sagarmala is aimed at bringing about a big change in India’s logistics sector’s performance by unlocking the full potential of India’s coastline and waterways.

• Current logistics system in India fall far short of international standards in terms of cost, efficiency, sustainability and safety. This eventually contributes to higher cost of doing business and higher prices of goods and services in the economy. For example, for power plants that are more than 1,000km from coal mines, the cost of coal transportation alone could contribute 30-35% of total cost of power produced (source: Ministry of Shipping, GOI).

• Sagarmala’s vision: To reduce logistics costs by a huge Rs 350-400bn for both domestic and EXIM cargo with optimized infrastructure investments.

• Some of these results would come about through direct cost savings, while others would happen through lower inventory-handling costs due to time (and reduced variability) in transportation of goods, particularly containers.

• These cost savings apply to current industrial capacities as well as future coast-proximate capacities for energy, material, marine, and discrete industries that could come up through port-linked industrialisation.

• Sagarmala also aspires to reduce carbon emissions from transportation by 12.5 MT/annum.

The concept of Sagarmala was approved by the Union Cabinet on 25th March 2015. As part of the programme, a National Perspective Plan (NPP) for the comprehensive development of India’s coastline and maritime sector WAS prepared and released at the Maritime India Summit 2016

The government has appointed an exclusive joint secretary to monitor the progress of Sagarmala projects. It will make equity investments of up to 49% in these projects through SPVs and undertake pre-feasibility studies, the cost of which would be considered an equity contribution. While there are no restrictions on the type of projects, the projects that are financed are likely to have IRRs of more than 12%.

About Sagarmala projects

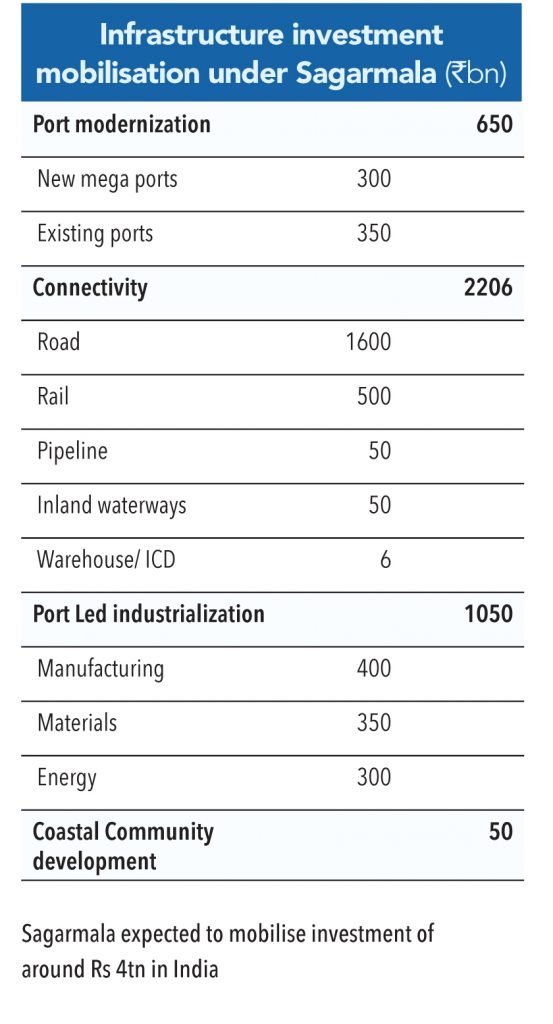

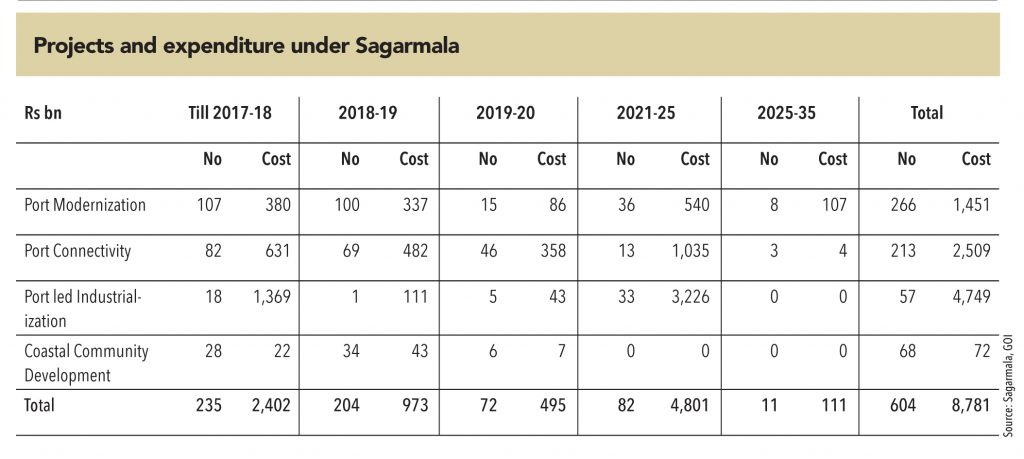

• As part of Sagarmala Programme, more than 604 projects at a cost of Rs 8.8tn have been identified for implementation during 2015-2035 across port modernization and new port development, port connectivity enhancement, port-linked industrialization, and coastal community development.

• As of September 2018, 522 projects worth Rs 4.32tn were under various stages of implementation, development, and completion.

The Coastal Berth Scheme

• The Coastal Berth Scheme is a key initiative under the Sagarmala Programme to promote the development of dedicated infrastructure for coastal shipping of goods and passengers across India’s major and non-major ports.

• The scheme provides financial aid for projects that promote coastal shipping at Indian ports.

• So far, 41 projects have been provided financial assistance of Rs 6.3bn under this scheme.

• The scheme has been extended up to March 2020 and its scope has been expanded to cover the cost of preparation of DPR and capital dredging at major Ports.

• Cochin Port has added a fourth cement terminal in a move aimed at directing a modal shift in the movement of cement, from road and rail to the sea, in a order to promote coastal shipping as a cost-effective and environment friendly means of transportation.

• ‘Penna Suraksha’ carrying 25,000 tonnes of cement from Krishnapatnam arrived at Q6 berth at Ernakulum Wharf, from the 4th cement terminal of the Cochin Port. As cement is a high-volume and lower-cost product, its movement through water transport could be a more viable option. Currently around 117mn tonnes cement moves through railways and a significant part of this can move through coastal waterways.

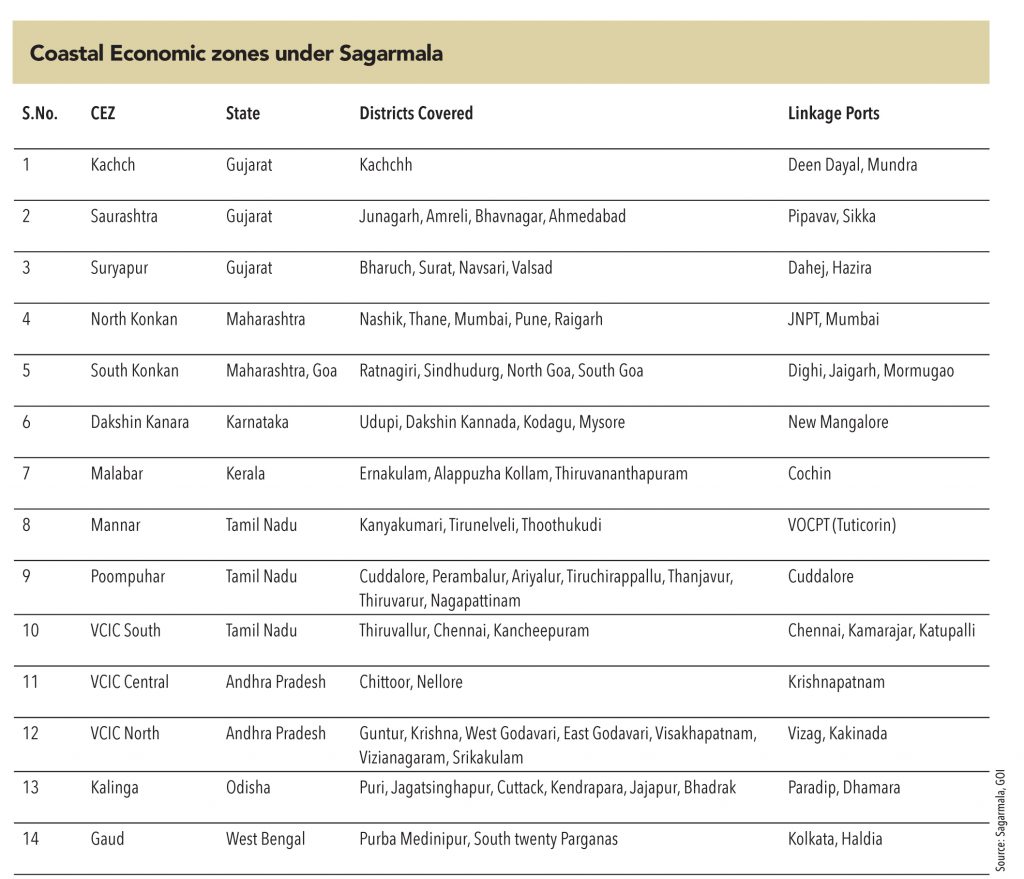

The government’s focus on coastal cluster development – with focus on multimodal logistics solution for the country – is expected to benefit coastal movement. Sagarmala envisages the formation of 10 such Coastal Economic Regions (CERs) along the coastline and inland waterways. To develop each CER, a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) would be formed with equity participation from the concerned state government and the Sagar Mala Company. The management of the CER SPV is vested with the state government.

Government studies under Sagarmala show that two optimization levers could lead to potential savings:

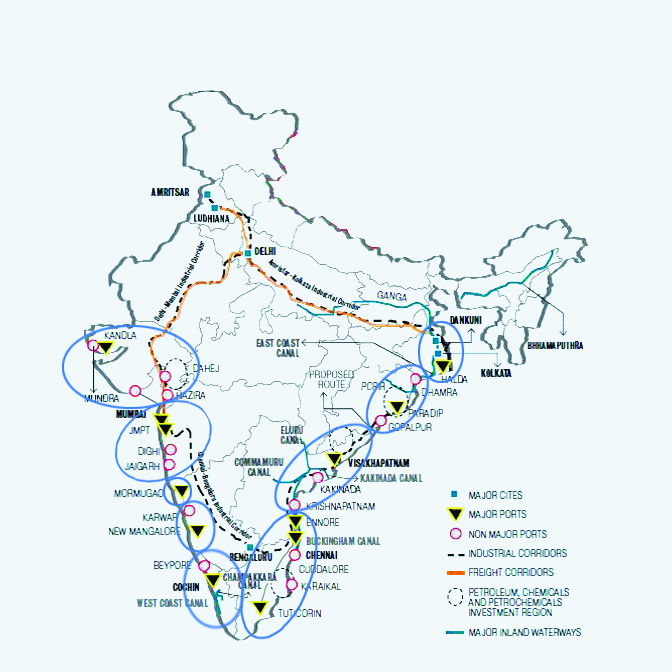

India has large coastline of 7,500km (mainland: 5,400km; island territories: 2,100km) mostly in its southern half, providing an opportunity for movement of from its west coast to its east coast. The immediate area for coastal trade comprises of 40 districts in five states on the west coast and four on the east coast. The hinterland covers an area of c.380,000 sq. km. Lakshadweep and Andaman and Nicobar group of islands in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal also form a part of the coastal area, dependent on coastal shipping for movement of cargo and passengers to the main land and for inter-island movement. The hinterland districts possess rich silica and minerals such as bauxite iron-ore, manganese-ore, and limestone, providing opportunities for coastal shipping. The distribution of minerals shows that there is a rich concentration of iron ore in Goa, in the Ratnagiri district of Maharashtra, the North Kanara district of Karnataka, the Calicut district in Kerala, Ongole district in Andhra Pradesh, and Cuttack district of Orissa. Lime stone is available on the coastal districts of Gujarat; Maharashtra and Orissa have rich deposits of bauxite.

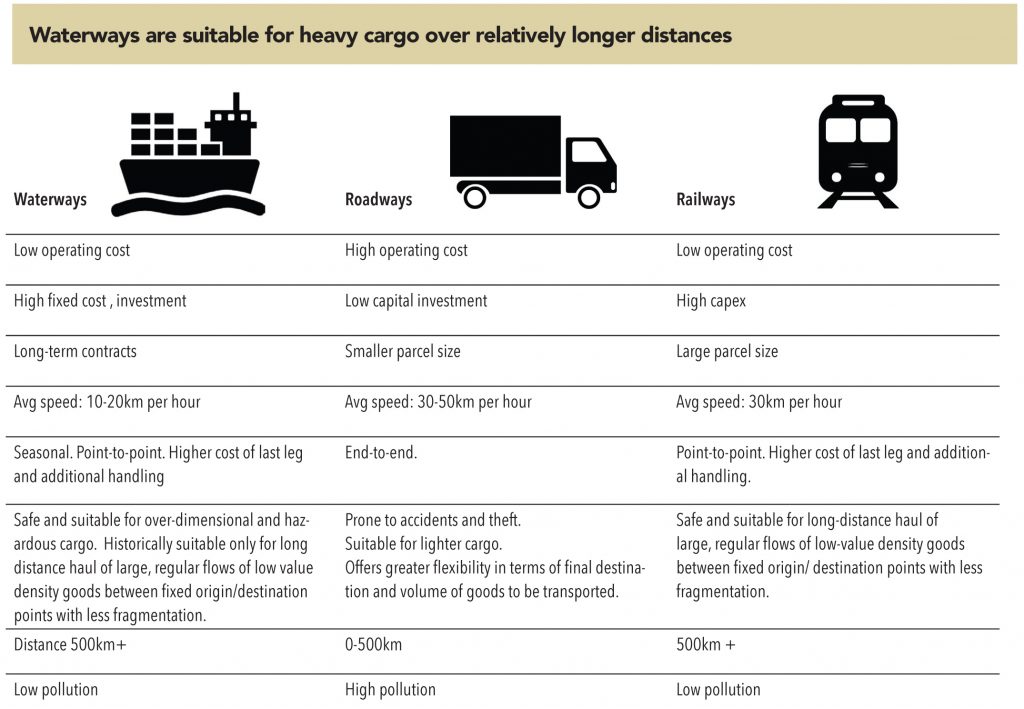

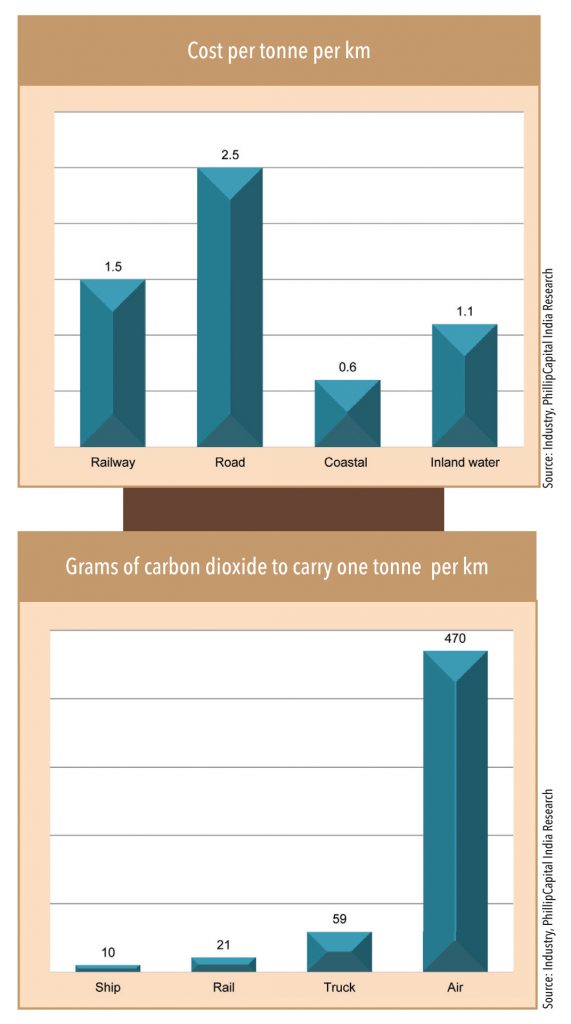

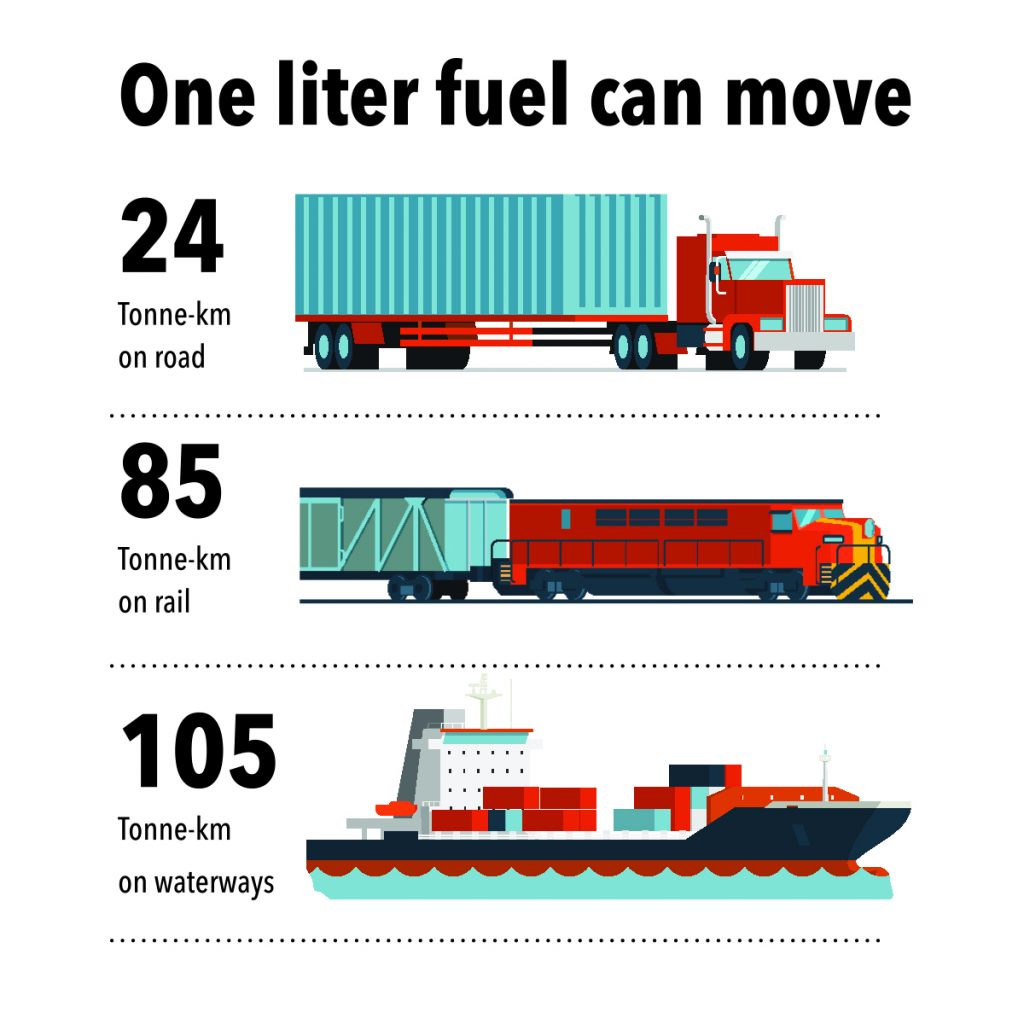

While road freight movement cost is Rs 2-4 per tonne per km, it is Rs 1.4-2.0 by rail, and as low as Rs 0.60-1.25 by waterways

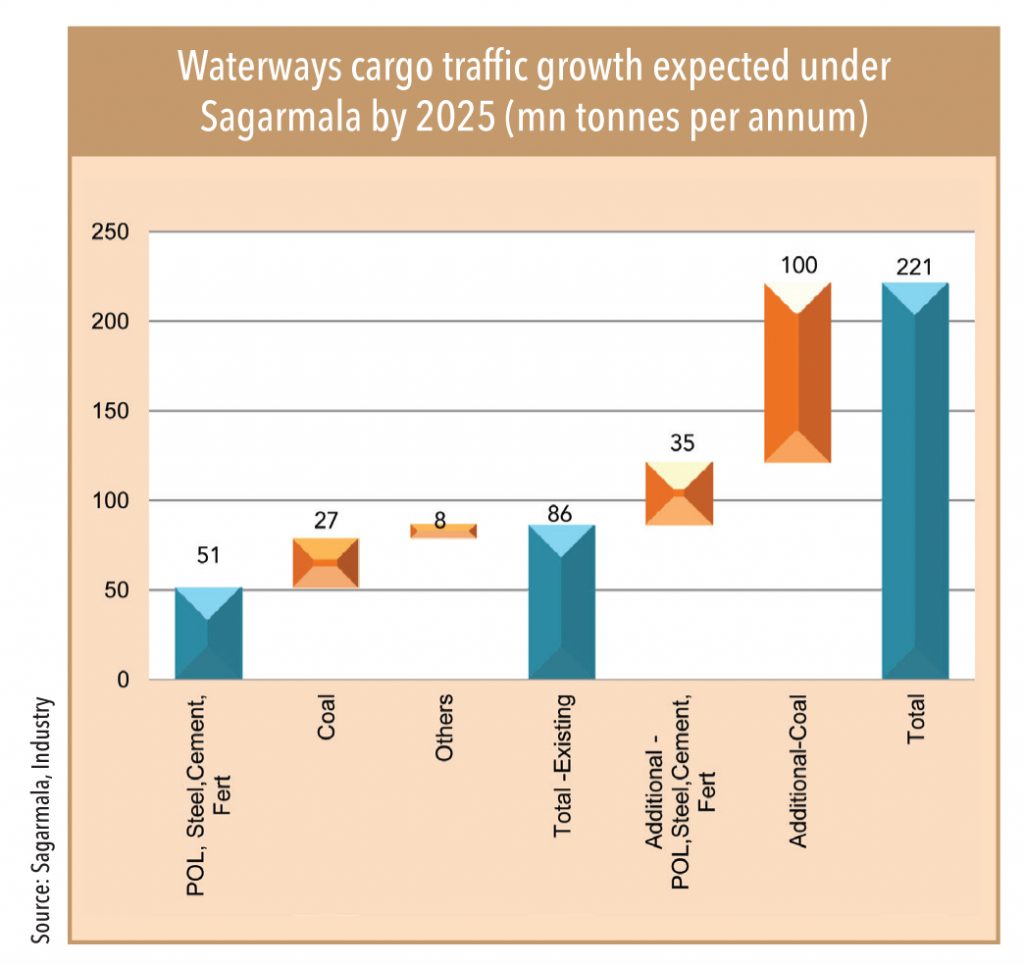

The National Perspective Plan of Sagarmala envisions a potential saving of Rs 210-270bn through coastal shipping of 220-230 MMTPA in key commodities such as coal, cement, fertilizers, iron & steel, food grains, and POL by 2025

Sectors that will benefit from Sagarmala

• Under the Sagarmala initiative, the government has identified nine commodities – steel, marbles, tiles, cement, automobiles, fertilisers, food grains, salt, and sugar, suitable for coastal shipping.

• To promote transportation of fertilizers through waterways under Sagarmala, the Nutrient Based Subsidy Policy was extended to coastal shipping and inland water transportation of fertilizers in November 2016, for reimbursement of freight. The subsidy was earlier only applicable to the movement of fertilizers by rail from plants or ports to rake points (railway stations) that are nearest to dealers in various districts for distribution.

• While rail is currently the primary long-distance mode of transport, government (shipping ministry) analysis indicates that a modal mix shift towards waterways can lead to a saving of c.Rs 9-10bn annually, assuming movement of c.10mn tonnes by 2025.

• Coastal plants in Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat have potential to move their products through coastal shipping (IFFCO and RINL are assumed highest potential).

Benefits for the coal industry

• Out of annual movement of c.750mn tonne coal in the country, only c.35mn tonne is moved through waterways while most of the remaining is moved through rail. More than 90 % of the rail routes relevant to coal are running at full capacity.

• Costal movement of coal has a potential of c.65mtpa per annum from current 32mtpa for power plants located near ports and up to 400km from the ports.

• Most of the movement is on the east coast from mines of Mahanadi Coalfields (MCL) via Paradip and Dhamra ports for power plants in the south. In the long term, additional coastal coal volume of c.30mntpa is likely from power plants with MCL linkage in Maharashtra and Gujarat and c.15mntpa from partial import substitution.

• With the expected ramp-up in domestic coal production, India may need to move 1.0-1.2bn tonnes per annum by 2025, creating pressure on the already congested railways.

• It is estimated that using the right infrastructure and institutional support, India can move 155-160 mtpa of coal, and save around Rs 65bn per annum.

• Since logistics contribute 30-35% of the cost of power generation, this initiative will also directly cut power costs by 50 paisa per unit for coastal power plants. A similar comparison of logistics costs for five other key commodities — POL, steel, cement, fertilizers, and food grains – revealed a total potential of 70-80 mtpa coastal movement, with a potential savings of Rs 45-56bn per annum. The National Perspective Plan of Sagarmala envisions the potential to save around Rs 210-270bn by 2025 through coastal shipping of 230-280 mtpa of these commodities.

The industry had demanded that the government should offer financial incentive of Rs 0.50 to Rs 1.0 per tonne per km to shipping companies to promote shifting cargo to waterways from roads and rail. Industry experts said that the government (specifically, the shipping ministry) came out with an incentive scheme of Rs 1 per tonne (up to 500km) in 2013, which was withdrawn immediately due to financial problems

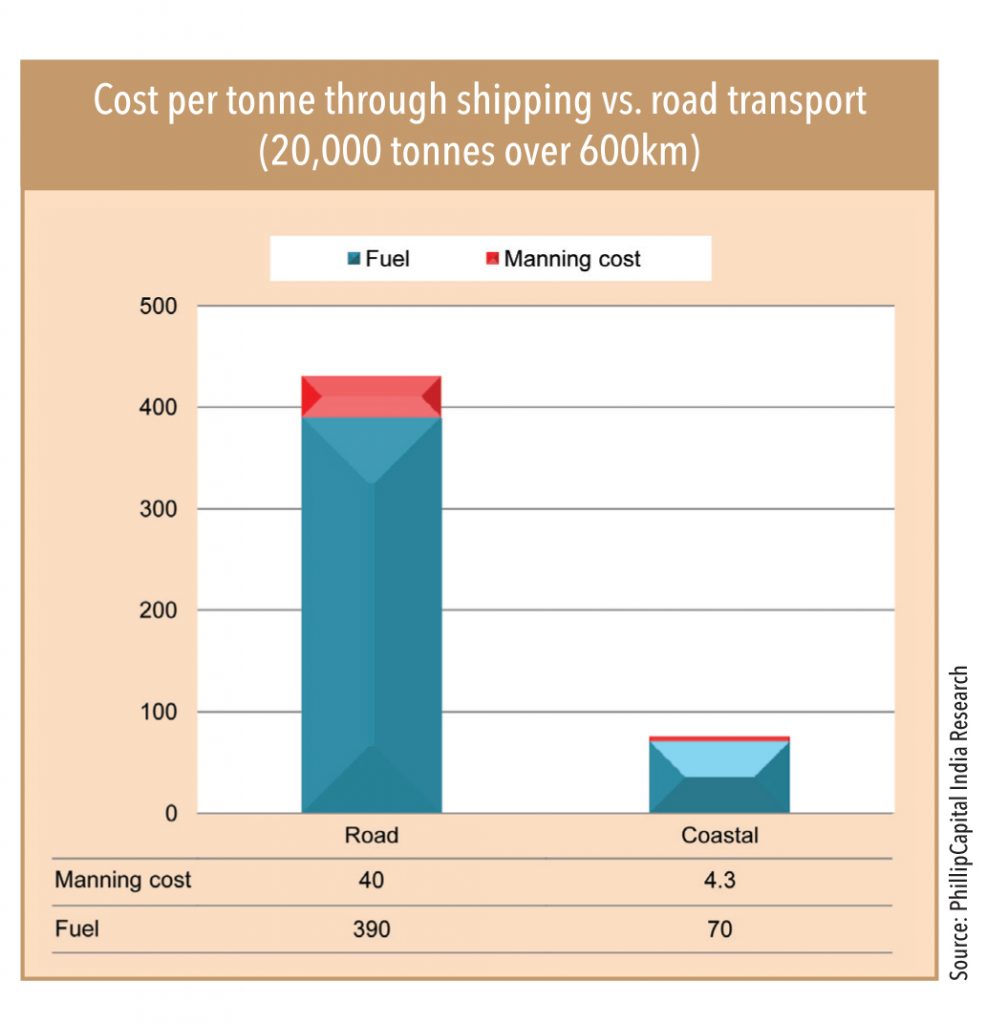

Shipping provides better operating leverage than roads and railways in transportation of cargo. The operating costs of shipping are significantly low in terms of fuel cost and manning costs per tonne of cargo carried. The fuel costs for container ships carrying 800 TEU over around 600km is around Rs 1.4mn compared to Rs 7.8mn for carrying the same cargo by road, saving around Rs 6.4mn in fuel per trip. Ships can carry around 20,000 tonne cargo in one voyage with around 10-15 employees, while it would require around 800 trucks (assuming per truck load of 25 tonnes) with 800+ drivers for the same cargo. Fuel accounts for around 25-30% of total operating costs for shipping, while for road transport it is around 35-50% of total cost.

Last leg of movement is the ‘Game Changer’

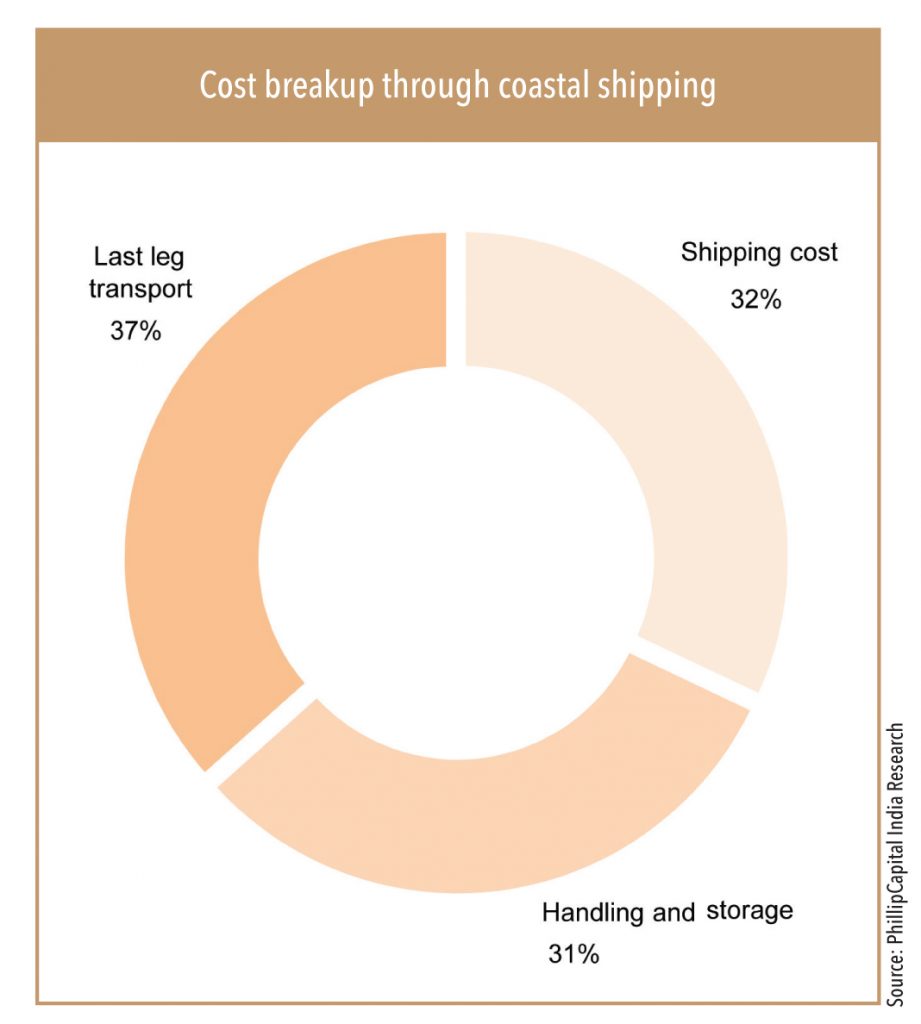

Though savings in voyage costs through shipping are huge, the major cost is in cargo handling and storage and providing last-mile delivery through coastal shipping. In most cases, the coastal cargo movement is limited to catchment areas of up to 100-150km from port locations due to limitations of rail connectivity or inefficient road network. Total cost of delivery in coastal shipping comes to Rs 1.6-1.8 per tonne km when we include the end-to-end cost of up to c.100-200km from ports, while by road it comes to Rs 2.0-2.5. Ships need to pay port charges, which include vessel-related costs and handling costs, which are around 31% of total costs. Another major cost is first and last leg transportation by road, which is around 37% of total cost. In most cases, transportation is more expensive in smaller ports as it is difficult to find truck availability to evacuate large parcels on time. The transport rate for trucks is also high in cases where there is no return cargo for ports from the hinterland or vice versa. “We target cargo within 50-150km around ports for coastal shipping, beyond which it is not viable and the charges are around Rs 600-900 per tonne,” said a senior management person of a shipping company operating on India’s west coast.

Coastal shipping is a low-hanging fruit and can be promoted with marginal investment, while inland waterways will require large investment and take time to evolve

Industry experts in coastal shipping in India said that after years of low growth they expect a sea change ahead based on policy support from the government and improvement in port infrastructure.

It has begun…

The sector has long-term growth potential and a number of companies such as Reliance Industries, JSW, Ambuja Cements, Narmada Cements, Kribcho, and NTPC (National Thermal Power Corporation) are already using the coastal mode for some of their cargo movement. Concor has started coastal shipping services from January 2019 between Kandla and Tuticorin ports with stops at New Mangalore and Cochin (two ships, weekly service). It has been able to scale up operations fast and was able to develop a new market for coastal shipping with around 400 containers per trip on a 700 TEU capacity ship. It is planning to increase services on India’s east coast to Bangladesh. Other listed companies with exposure to coastal shipping are Shipping Corporation of India (SCI), Shreyas shipping, Allcargo, and and TCI seaways. However, Shreyas Shipping has been able to increase its cargo and fleet over the past five years, while Allcargo and Gati have reduced exposure to the sector. In this segment, the success of players largely depends on the type of cargo they cater to. Ideally, it should have a good mix of exim and domestic operations, asset profile, and route rationalization.

…but problems need to be overcome for it to gain momentum

While the government promoted carrying cars through coastal movement, after some trial runs, it did not take off. This was because the frequency and delivery schedule was difficult to match with road transport.

The problems:

• Most dealers need delivery in a short time and visibility in tracking the cargo movement.

• Due to the very large order size for shipping and higher transit time, storage requirement increases significantly for the logistic chain, and inventory costs for dealers rise.

• For auto distribution, existing road operators are already quite well established and they provide flexible pricing for cargo movement.

• Initial high investment in shipping is also a limiting factor, without long-term contract and policy visibility private players are reluctant to invest.

Costs remain prohibitive, especially for transportation of vehicles

For roll on-roll off vessels port dues are calculated based on Gross Registered Tonnage (GRT). The GRT for normal vessels is around 66% of DWT (dead weight tonnage) but for Ro-Ro vessels, GRT is at times 400% more than DWT, which makes it very costly for carrying vehicles through ships. In Indian ports, dues for specialised vessels like a car carriers are among the highest in the world. However, the Chennai Port Trust offers ‘wharfage’ at an economical rate of Rs 500 per unit as against the actual rate of Rs 1,200.

The EU has a concessional rate for RoRo vessels, while in India, most ports charge based on GRT (expensive)

An under-developed transport market at smaller ports and poor connectivity are major issues for coastal movements. “We will not shift (from road to ships) just for saving 10-20% in transportation cost, as reliability and inventory cost is a major issue for coastal shipping,” said one SCM (Supply Chain Management) Head. With improvement in road infrastructure, travel time by road is the same or sometimes better than coastal movement, largely due to delays at ports.

Experts in coastal shipping said that another issue in Ro-Ro vessel movement through coastal shipping is the strong lobby of road transporters. Road transport in India is not strictly monitored and companies were able to move cargo with under-reporting of invoices and paying duty on only 10-20% of cargo value, which is not possible via shipping.

Also, familiarity with officials helps transporters to overload cargo, which is also not possible in shipping.

“We started Ro-Ro service from Cochin to Gujarat and vice versa with a loading capacity of c.120 trucks per voyage, but the ship can take a maximum100 trucks only during actual operations,” said a promoter of a domestic shipping line. There is a high level of transparency in shipping movement while it is fairly murky in road movement. In shipping, all cargo-related documents are checked, and overloading is strictly not allowed, but via road, it is quite common especially by unorganised transporters.

Using RoRo ships for moving trucks reduces the wear and tear of tyres and engines and saves fuel; but most truck drivers prefer to travel by road as they get additional income on the way by carrying passengers and also through fuel theft due to which drivers are not keen on using coastal mode.

Going forward, industry experts anticipate strong regulation follow up (which is relatively easy now post GST and e-way bill) on the road side movement is also important as it create unfair competition.

Cargo movement at Mumbai port

However, implementation of GST and E-way bill has now renewed hopes for stricter compliance in road transport, which can reduce under-invoicing significantly. The implementation of BS-6 norms and AC cabins in trucks are also expected to increase road-transport costs, which can help coastal shipping to grow.

Cargo handling needs to be improved

Ports and berths are custom notified and cargo handling is performed under the surveillance of customs. Berth availability for coastal shipping and segregation of domestic and exim cargo is a major concern for many ports in India. Most of the success of coastal cargo in the EU is due to the handing of cargo in small exclusive ports with efficient hinterland connectivity. In China, ports are developed along rail and road connectivity with a network of inland waterways, which provide efficient evacuation of cargo. In India’s largest container port, JNPT, the share of rail movement is only 15-18% and the share of coastal movement is negligible.

Industry experts believe coastal movement between JNPT and Mumbai Port could provide a viable solution for storage and distribution of cargo for Mumbai City. “Due to poor infrastructure at Mumbai port and restrictive labour norms, no private player is interested,” said a retired senior officer. Most cargo meant for Mumbai City is moved by trucks from JNPT to Bhivandi for storage. Basically, it needs to cross the city by road for distribution. This not only increases logistics cost, but also causes pollution and congestion in the city. A viable solution would be to move cargo directly from JNPT Port to Mumbai Port via sea.

Unfair competition from foreign players in coastal shipping

Indian operations on voyage-to-voyage basis are 32% costlier than similar services provided by foreign shipping companies operating in India, mainly due to difference in taxes and bunker, manning, and finance costs.

• Tax difference: Indian flag ships need to recruit Indian crew as per manning norms prescribed by the Director General of Shipping (DG Shipping). However, Indian people working on foreign flags do not pay income tax while on Indian ships they have to pay income tax. Due to this, Indian ship owners have to pay higher salary to compensate for the tax outgo and find it difficult to get a good skilled crew.

• Finance for shipping needs to be long-term specialised: There is no specialised or dedicated institution to provide finance for shipping in India and traditional banks treat these as industrial loans with tenures of 6-7 years, while the life of a ship is around 20-25 years. Cash-flow pressure on domestic players is higher compared with foreign players, who receive loans for 10-12 years. Therefore, there is a

The government has taken steps to encourage coastal shipping – including reducing GST on bunker used in Indian vessels to 5% in April 2018 from 18% earlier and providing 40% discount on cargo related and vessel related charges for coastal ships (except for coal and iron ore). To promote RoRo vessels (coastal car and truck movement), the government offered 80% discount on vessel and cargo related charges for two years, priority berthing, and green-channel clearance for faster evacuation at major ports. It also allowed reimbursement of freight subsidy on primary movement of subsidised urea.

Key policy initiatives to promote coastal shipping

• Moderating the manning and technical requirements for vessels operating within Indian territorial waters through a River Sea Vessel notification.

• Declaring the inland vessel limits for facilitating coastal trade operations.

• Issuing coastal shipping rules for coastal vessels operating within 20 miles off the coast.

• Exempting Customs and Central Excise duty on bunker fuels (IFO 180 and IFO 380 CST) by Indian flagged coastal container vessels. Post GST regime, tax rate reduced to 5% from 18%.

• Discount raised to 80% from 40% for marine charges for two years to promote RoRo movement. Vessel related charges or marine charges include port dues, berth hire, and pilotage.

• Bringing abatement of service tax at 70% for coastal shipping at par with road and rail. Including abatement of service tax in coastal shipping, fertilizer movement through railways, roadways along with inland waterways and shipping, 80% of tax relaxation for vessels and development of cruise ships.

• Simplification of customs procedures.

• Green-channel facility provided at major ports for faster evacuation of coastal cargo. Major ports have been directed to provide priority berthing to coastal vessels to reduce waiting times of such vessels at the major ports. Major ports are required to accord priority berthing (at least one berth), irrespective of origin and destination of cargo.

• Cabotage relaxation for specialised vessel and select cargo.

• Proposed cargo preference for coastal shipping if vessel is built in India.

Government policy changes that have had a significant impact on coastal shipping are:

(1) Reduction in duty on fuel.

(2) Permission to mix exim and domestic cargo during voyage.

(3) Relaxation of Cabotage law and right of refusal.

(4) Concession in port-related charges for coastal shipping with priority berthing at major ports.

Duty benefit on bunker fuel

The duty reduction on fuel used for coastal shipping was a long-awaiting demand from the sector, as it accounts for around 25-30% of the voyage cost. Earlier, due to very high tax difference, bunker cost for domestic operations was almost double the bunker cost for foreign-going ships. Fuel for foreign-going vessels was exempt from custom and excise duty while duties were applicable for coastal shipping. The government removed this disparity by providing exemption to coastal shipping as well.

However, while the government has provided tax benefit for bunker and reduced GST to 5% from 18%, OMCs (oil marketing companies) in India keep prices for bunker high compared to fuel prices prevailing in the international market. Reliance and Essar do not supply bunker, only PSU OMCs – IOC, BPCL and HPCL – do. Indian players suffer a 20% disadvantage to foreign vessels in term of fuel purchase cost. In April 2019, bunker price for Indian flag vessels was US$ 468 per tonne vs. US$ 439 per tonne for foreign ships buying fuel outside i.e. Singapore or other ports and come to India, as per an industry source.

Allowing to mix exim and domestic cargo

Coastal ships were restricted from mixing domestic and exim cargo, resulting in lower utilization of ships and making coastal operation unviable. The Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs (CBIC) now permit Indian-flag vessels to make calls en-route at Sri Lankan and Bangladeshi ports during their domestic services. “Earlier Indian vessels were not permitted to make calls into foreign ports, even when such ports were on their domestic-service routes between the east and west coast ports of India. So Indian ships engaged on such trades were unable to make optimum use of their space and were incurring higher cost of transportation on both export-import and domestic coastal cargoes,” said CEO of Indian National shipping association.

Relaxation of the Cabotage rule

India’s domestic shipping industry was given preference to move coastal cargo through right of first refusal (ROFR) clause under Cabotage rule – this gives Indian shippers a chance to match the lowest rate offered by foreign ships as well as restricts select operations to only Indian flag vessels. In May 2018, the Indian Shipping Ministry changed its Cabotage rules so that foreign-flagged ships would no longer be required to obtain a special licence to perform coastal operations. in India. Previously, these licences would only be offered if there were no Indian ships available to carry out tasks. Since this relaxation, international shipping companies have been able to move export and import containers along the country’s coasts.

The industry’s experience about relaxation of the Cabotage rule is mixed.

• People supporting relaxation of Cabotage believe that the domestic fleet growth was not in line with cargo opportunities and that there is a shortage of domestic capacity to carry cargo, which is why foreign players need to step in. “Coastal shipping is bound to increase over a period with the government’s announcement on the relaxation of Cabotage law,” said one operator.

• The government has been giving a ‘No-Objection Certification’ for in-chartering of over 150 vessels into the country each year, since domestic players are not in a position to provide ships for coastal and inland water transport in such a big way.

• The move is also expected to address the issue of empty containers accumulating at certain Indian ports, while others face shortages. Sources in the sector have said that foreign shippers would be able to allay the costs that would otherwise be involved with repositioning these empty containers and will increase transshipment cargo

Coastal shipping is bound to increase over a period with the government’s announcement on the relaxation of Cabotage law,”

An operater

• Market players said that shipping lines were able to redirect c.95,000 TEU (loaded 83,000 TEU) of containerized freight to Indian ports through transhipment in February 2019, which was the highest monthly incremental gain since the relaxation of the Cabotage rule.

• The pricing flexibility at minor ports with better infrastructure is expected to increase the role of minor ports in developing coastal shipping and transhipment. The success story of Krishnapatnam Port in south is an example. At 112 nautical miles north of Chennai Port, it is emerging alternative private port for transhipment. Out of a total record throughput of 506,000 TEU at Krishnapatnam during FY19, as much as 230,682 TEU came from transhipment movement.

• DP World’s International Container Transhipment Terminal (ICTT), or Vallarpadam Terminal, at Cochin Port also ended FY19 on a solid note, with volume up 7% yoy to 594,592 TEU.

“India’s domestic shipping industry needs to be given a level playing field on all operating parameters, on par with foreign shipping companies, especially in all aspects of taxation and law,”

– Mr. Anil Devli CEO INSA

• Indian players have opposed this move and the matter is under review.

• Indian shipping is able to compete with foreign shipping companies on all international trades, but is unable to compete on the Indian coast due to non-availability of a level playing field.

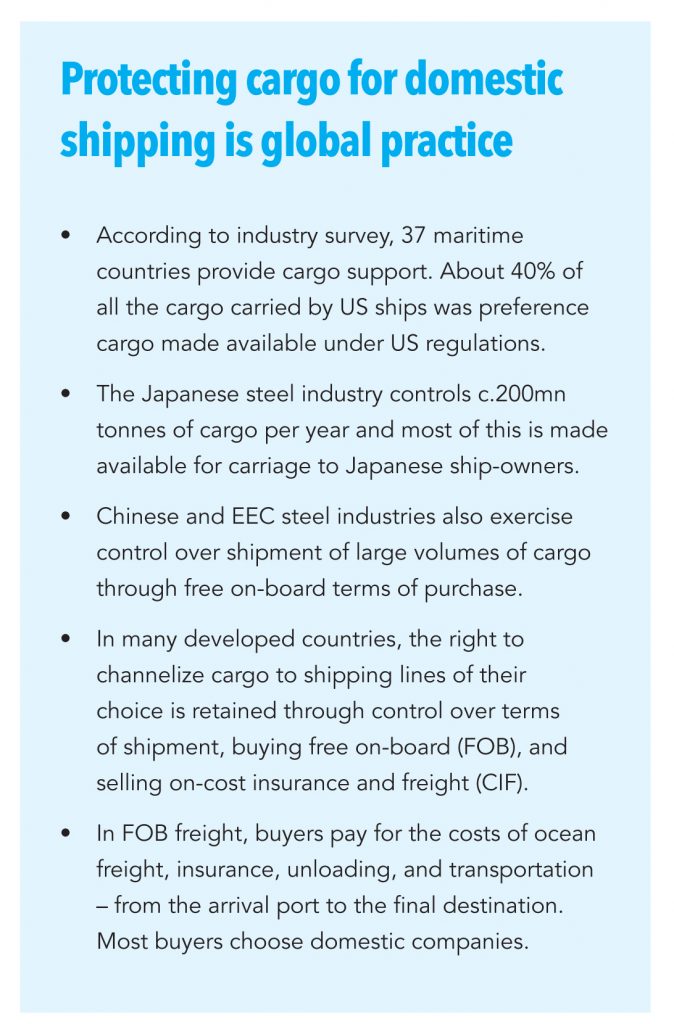

• Domestic players pointed out that all countries with a long coastline, including the US, do not encourage foreign ships to ply their trade along their coast. They believe that the relaxation in Cabotage may be considered only on a case-to-case basis and only in case Indian ship owners are not able to move the cargo.

• “Foreign companies have only moved empty containers from JNPT to Mundra port and from Chennai to Vizag,” said the MD of a domestic shipping company. Indian-registered shipping companies say that the move has helped private ports in India, while domestic shippers are at a disadvantage.

• “ India’s domestic shipping industry needs to be given a level playing field on all operating parameters, on par with foreign shipping companies, especially in all aspects of taxation and law” said Mr. Anil Devli CEO of INSA. “This will lead to greater FDI in Indian shipping leading to growth of tonnage, taxes and employment”.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access