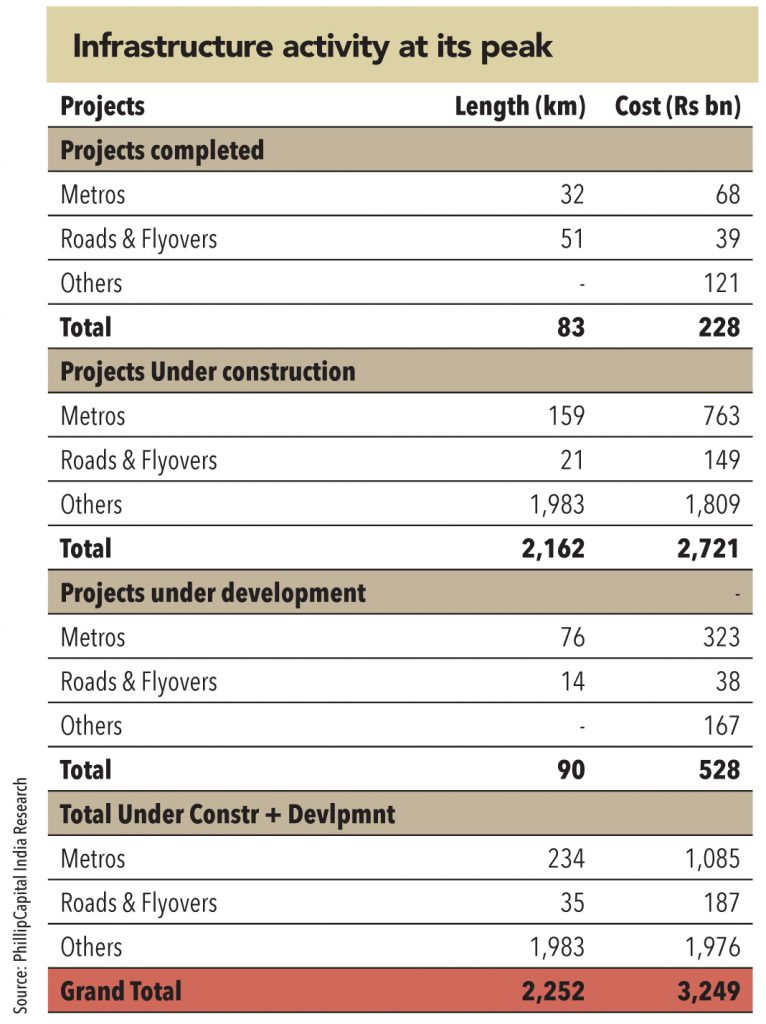

Mumbai has seen heightened level of award and execution activity over the last five years. That the projects now being awarded should have been completed years ago, is an altogether different matter. But the lethargy and inactivity of the earlier governments for over 15 years (just four projects of significance completed during 1999-2014) finally gave way to five years of nimble-footedness and action. Scores of road/metro/flyover projects have been conceptualized, awarded, and completed over the last five years. Together, major projects have over Rs 3trillion riding on them. When all of them are completed (hopefully by 2023) – the infrastructure of the city will look completely different from today.

Overall, more than Rs 200bn of large projects were commissioned in the last five years. At the same time, currently, a mammoth Rs 2.7trillion of projects are under construction and Rs 500bn of projects are at the conceptualization stage (excluding the Bullet Train and Hyperloop).

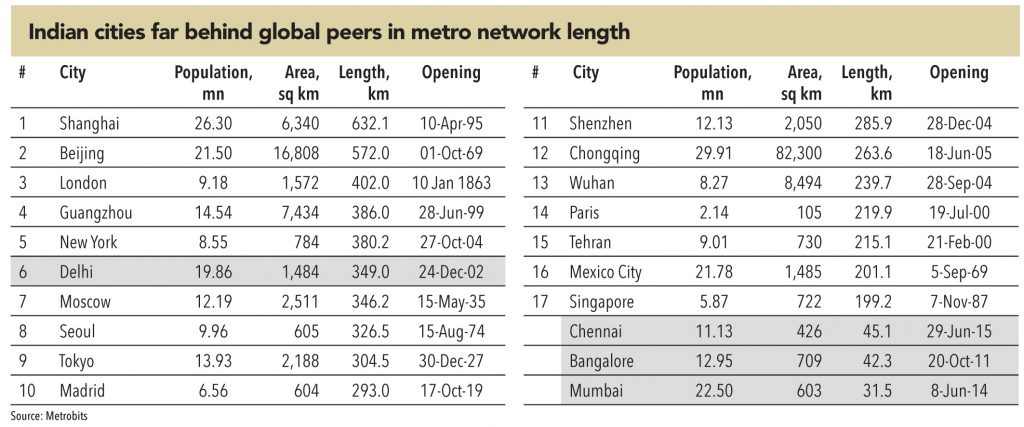

While Mumbai should have been one of the first cities in the country to start a metro service (given the paucity of land for building roads), it has been a laggard amongst all Indian metros. Not just Delhi, even Bengaluru started its metro service in October 2013 (before Mumbai). However, over the last five years, the government bodies (especially the state government and MMRDA) have sprung into action and have awarded an unprecedented number of metro projects in the city.

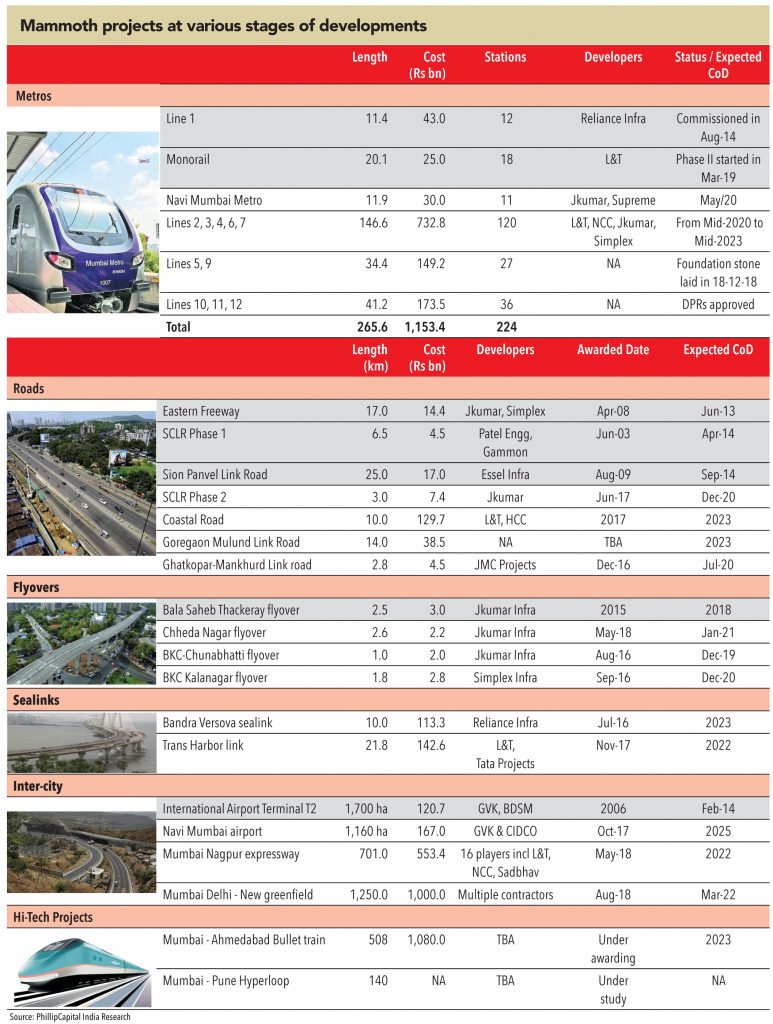

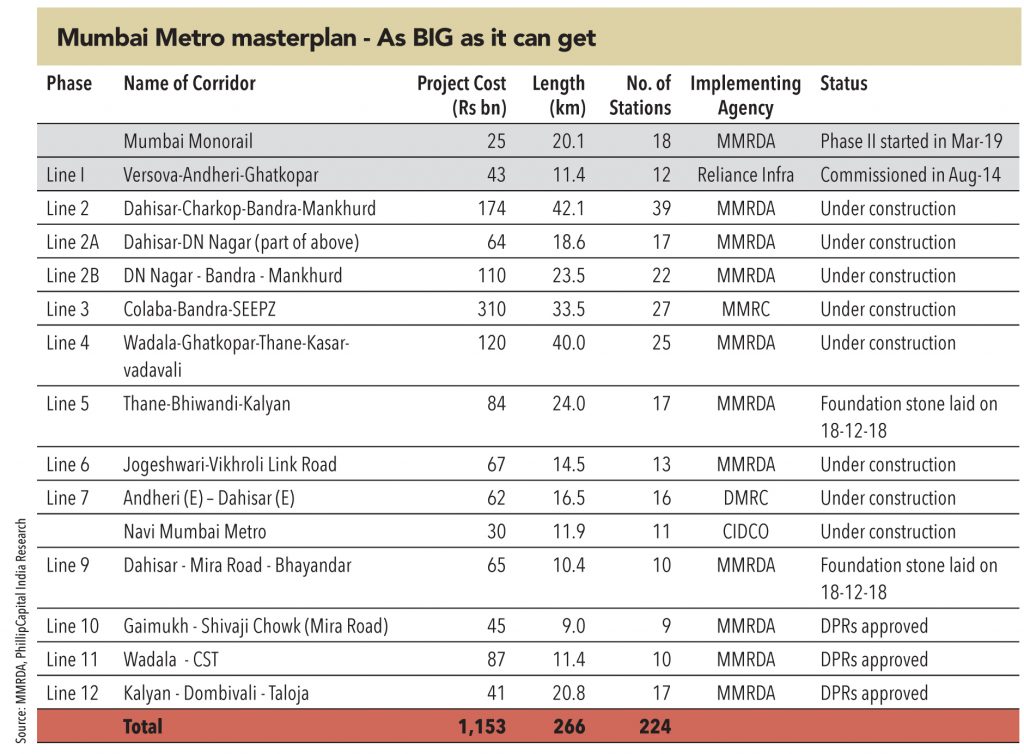

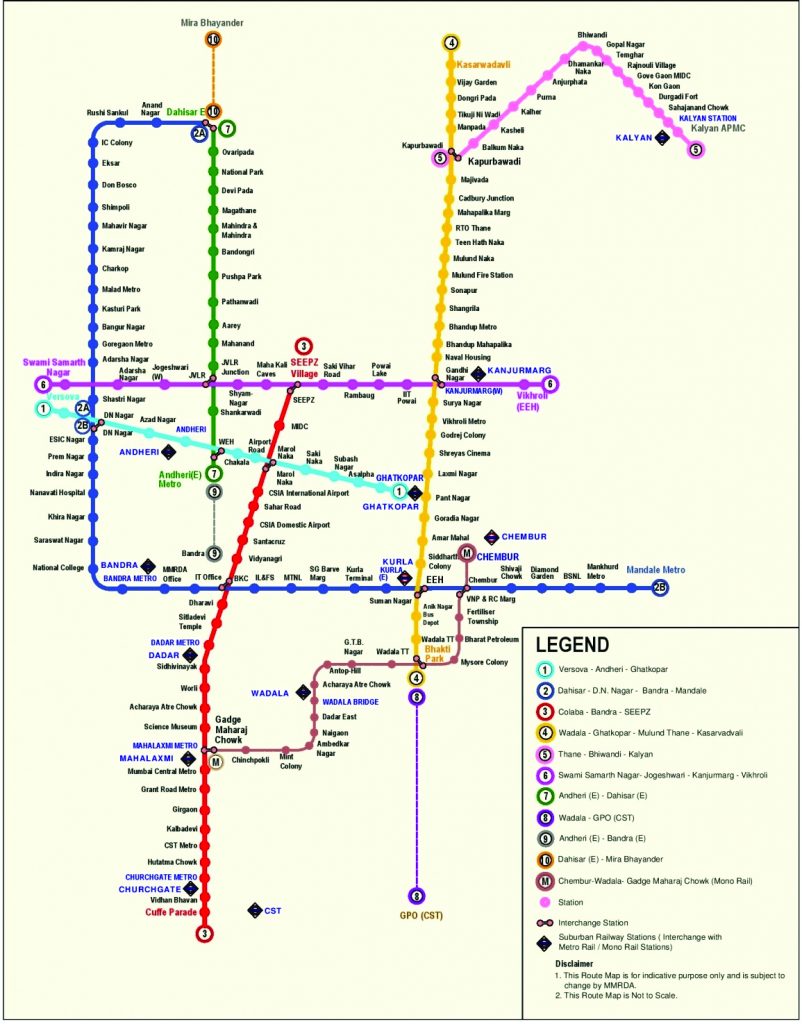

The MMRDA metro master plan has undergone so many changes in the past three years that it becomes difficult to believe any new route being proposed till its plan and funding are approved and accepted. The current Mumbai Metro masterplan envisages a mammoth network of 265km of metro projects to be built at an investment of Rs 1.1trillion. Of this, only 32km is currently operational (Line 1 and Monorail). The significant achievement of the current government is that almost 160km has been awarded over the last five years – with Rs 762bn riding on it. Never in the history of any city across the world has metro network witnessed an expansion of this scale, in one go. That this massive infrastructure push has created havoc on roads, with almost every major road/corner dug-up, is another matter!

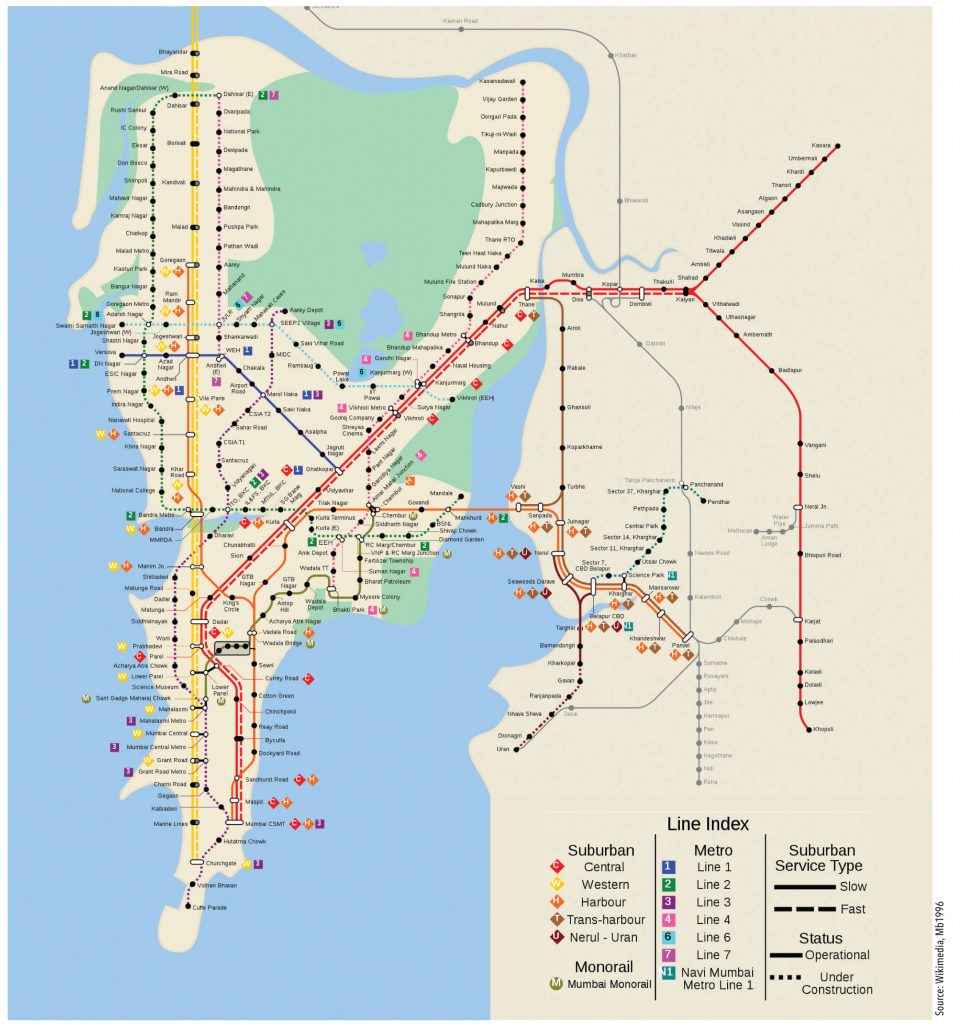

This massive expansion of metro network is sure to change the transport landscape in the city. From an operational length of just 32km, the Mumbai metro network is expected to touch 200km by 2023 – making it the second largest metro network in the country (after New Delhi at 350km) and the 17th largest in the world (overtaking Singapore at 199km).

The travel time for residents, congestion on the roads, and traffic in the local trains are all expected to be impacted positively by this expansion.

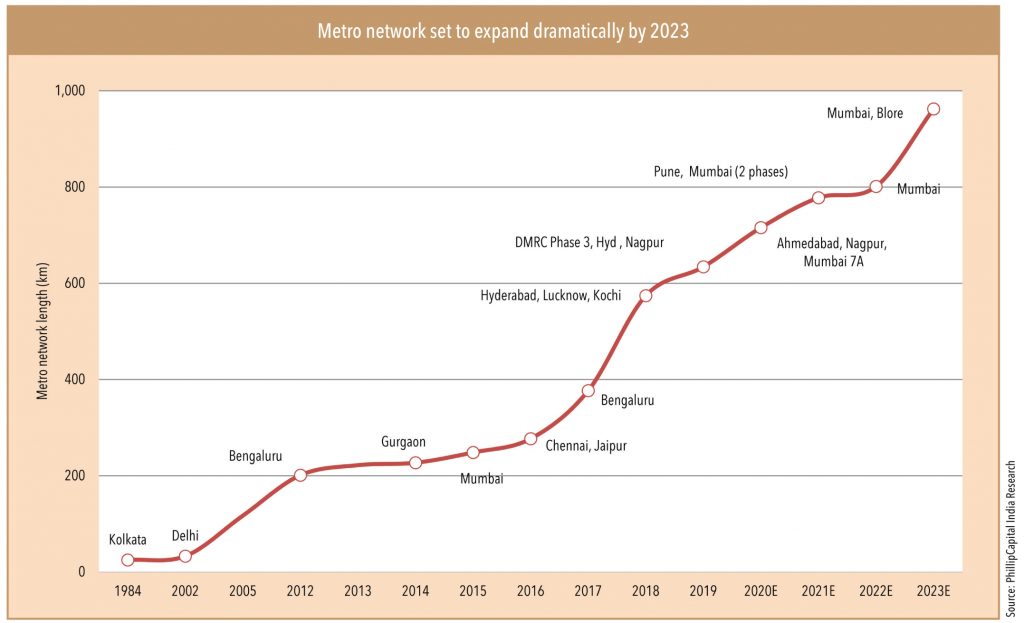

To provide a perspective, while the metro network in the entire country is expected to grow from 635km to 960km over the next 4 years (growth of 52%) – the Mumbai metro network will grow from 32km to 190km over the same period (growth of 503%). From accounting for just 5% of the total operational metro network in the country in 2019, Mumbai’s share will jump to 20% in 2023. The expected ridership on the metro network in 2023 is expected to be over 5mn passengers (daily) – amongst the highest in the world.

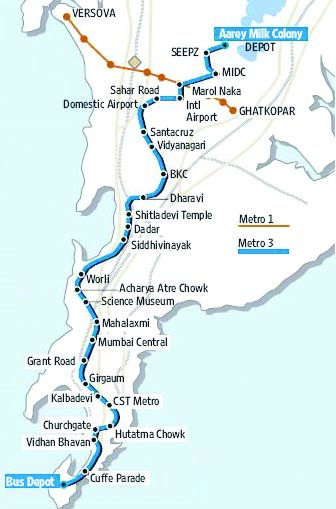

The long wait for Mumbai’s entry into the ‘Metro club’ finally ended in May 2014, when the first phase of Mumbai Metro, built by a Reliance Infrastructure led consortium on a PPP basis, was thrown open to public. The service has since significantly decongested the suburb of Andheri and provided much needed connectivity between western suburb of Versova to the eastern suburb of Ghatkopar – reducing travel time between the two ends from 90 minutes to 21 minutes.

Even though the project was much delayed, the construction of the Mumbai Metro can be hailed as an engineering marvel — the track was laid through one of the most densely populated suburbs of the city (Andheri and Ghatkopar). The company had to deploy ‘form traveller’ to build the viaduct above the western express highway (an example of poor and myopic planning, visible all across the MMR region).

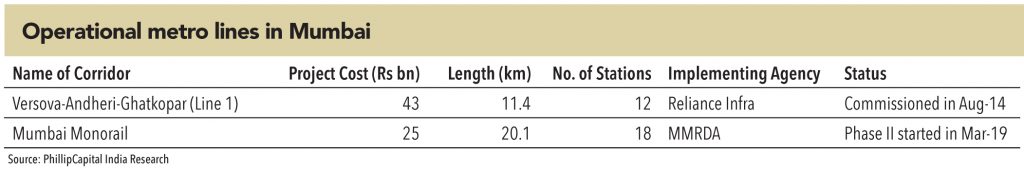

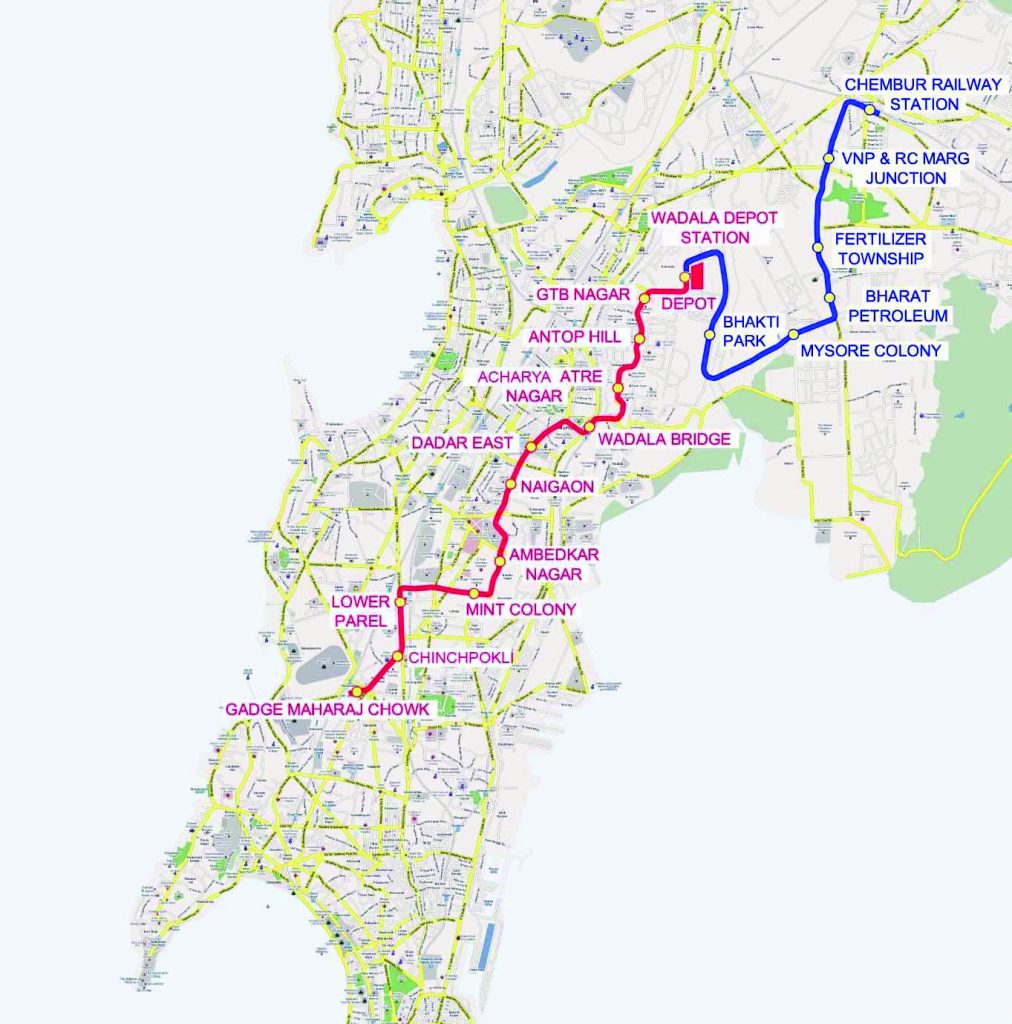

In December 2013, Phase 1 (Chembur-Wadala) of the Mumbai monorail, constructed by L&T, was thrown open to the public. Post commencement of Phase 1, the project faced multiple hurdles – in the form of accidents on the operational part and delay in Phase 2. Eventually, Phase 2 was commissioned in March 2019 – making the entire 20km line operational. Now the line connects the suburbs of Chembur to Mahalaxmi – and will form a critical part of the city’s metro network, once Line 4 (Wadala-Ghatkopar-Thane) become operational.

While monorail has been derided as ‘joyride’ by lot of people and media publications, GV believes most people are missing the objective of this line. The line traverses through the narrowest and densely populated lanes of the city (Sewri, Parel, Mahalaxmi) and the thin structure of the monorail allows it to bend on sharp turns, which a metro rail would have not been able to do. GV believes that the MMRDA has been pragmatic in this case, and adhered to horses for courses ideology – enhancing the connectivity of those areas of the city that might have otherwise been deprived of the metro connectivity.

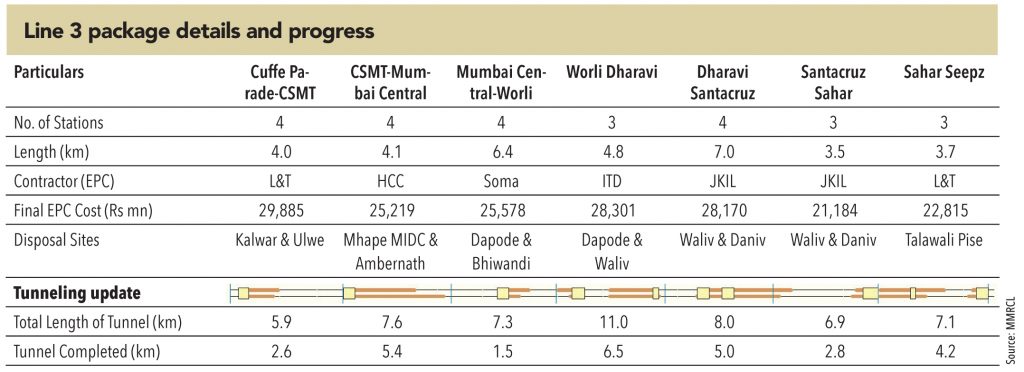

Line 3, when first envisaged, was completely ridiculed by the residents of the city. A 34km long fully underground metro line will take a decade to complete (if it ever starts) – in a city where a 10km overhead metro took 5 years to complete! But call it the will or the vision of the government bodies (state government, MMRDA, DMRC) – civil contracts for the line were announced in October 2015, and the revised contracts were formally signed in December 2016. The 34km completely underground metro project is expected to cost c.Rs 300bn – with almost 40% of the funding coming from JICA.

Line 3 proposes to connect some of the key areas of the city, that are not connected by the local train network (viz Worli, Siddhivinayak, Airports, Marol and SEEPZ) – along with providing interconnectivity with the train network. The completely underground network is being built with the latest technology and adequate safety measures. While two packages of the MM3 in Mumbai faced a few litigations initially, which delayed work by about 6 months, other projects have seen smooth and steady execution. All packages are making good progress, and the line is expected to be thrown open to the public by 2023.

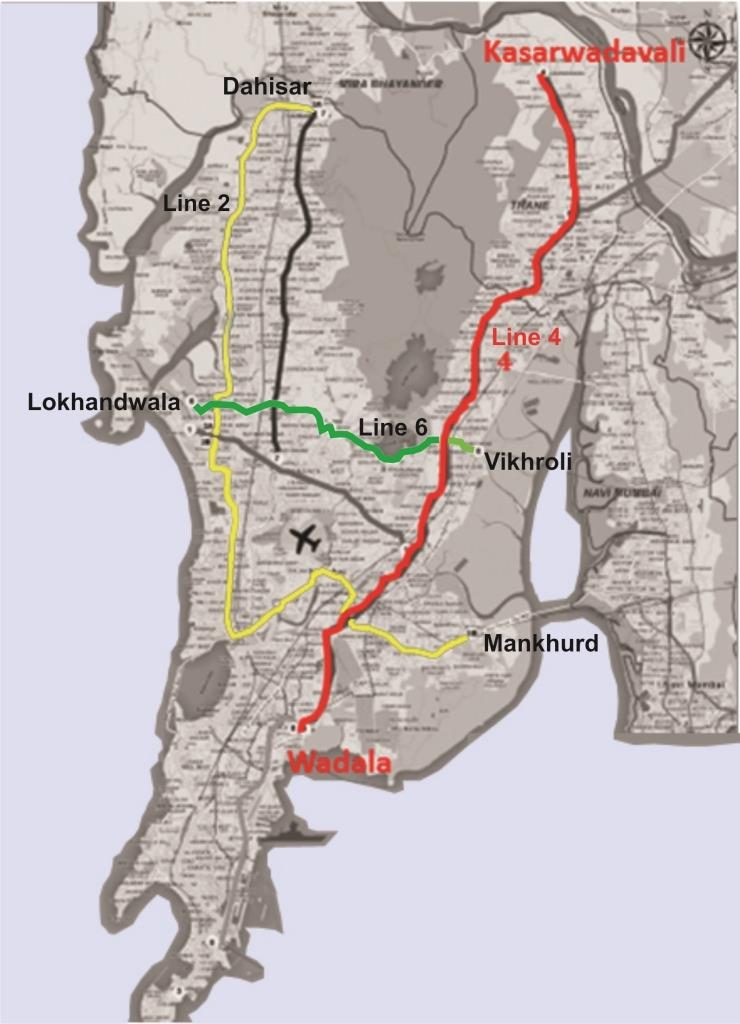

Like most projects in the city, Metro line-2 also has a long and interesting history. It was first awarded on a PPP basis to Reliance Infrastructure (the same developer who built the line 1) in 2009. But funding and guarantee issues led to the termination of that contract in 2014. Thereafter, multiple attempts were made to revive the project in different formats (PPP/EPC), but without any success. Finally, the government decided to break the line into two parts – 2A from Dahisar to Andheri, and 2B from Andheri to Mankhurd.

Line 2A was inaugurated by the PM, Narendra Modi, in Oct-2015, along with a line parallel to it – line 7. Line 2A and 7 will together cost Rs 126bn, for which 40% funding is being secured from JICA. Winners of the two EPC packages for line 2A (both were won by JKumar) were announced in June 2016. Civil work on this line is in full swing, and expected to be completed by 2020. The government, that hoped to make the line operational by 2019 (before state elections) will only be able to see it in operations by 2021.

Line 2B was divided into four packages, and winners were announced in August 2017. However, most bids were more than 25% higher than MMRDA estimates. Hence the packages were revised (four packages reorganized into three) and the winners were announced in March 2018. Civil work on this line has started in 2018, and is expected to be completed by 2021. The line is expected to be fully operational by 2022.

Overall, line 2 – 42km; Rs 174bn – is expected to provide cross-city connectivity from western suburbs to Navi Mumbai, through the CBD of BKC. Combined with line 3 and line 4, it links almost every part of the city with BKC, and the island city.

Just like line 2, that provides longitudinal metro connectivity to the western suburbs of the city, line 4 seeks to do the same for the eastern suburbs. The line will connect Wadala and Ghatkopar to the far-flung eastern suburbs of Thane and Kasarvadavali. The line will have interchange with Monorail (at Wadala), Line 1 at Ghatkopar, Line 2 at Mankhurd, and Line 6 at Eastern Express highway. Civil works for Line 4 were awarded in August 2017. However, like line 2B, most bids were more than 25% higher than MMRDA’s estimates. So the packages were revised, and the winners were announced in March 2018. Civil works on this line have started in 2018, and are expected to be completed by 2022. The line is expected to be fully operational by 2023.

Line 6, though the smallest of all, is perhaps THE most important line in the city’s metro network. This line and Line 1 are the only ones that provide lateral connectivity, as opposed to longitudinal connectivity provided by other lines. Line 6 will provide interchanges with Line 2 (at Jogeshwari-W), Line 7 (at Jogeshwari-W), line 3 at SEEPZ, and line 4 at EEH.

Civil works for the Line 6 were awarded in August 2017 and execution started in 2018. Civil works are likely to be completed by 2022. The line is expected to be fully operational by 2023.

Globally, most cities with well-developed public transport provide interconnectivity between all modes of transport. So, while metro/monorail lines cross each other at multiple locations, most stations are co-incident with major railway and bus stations. There is also direct connectivity to airports and jetties.

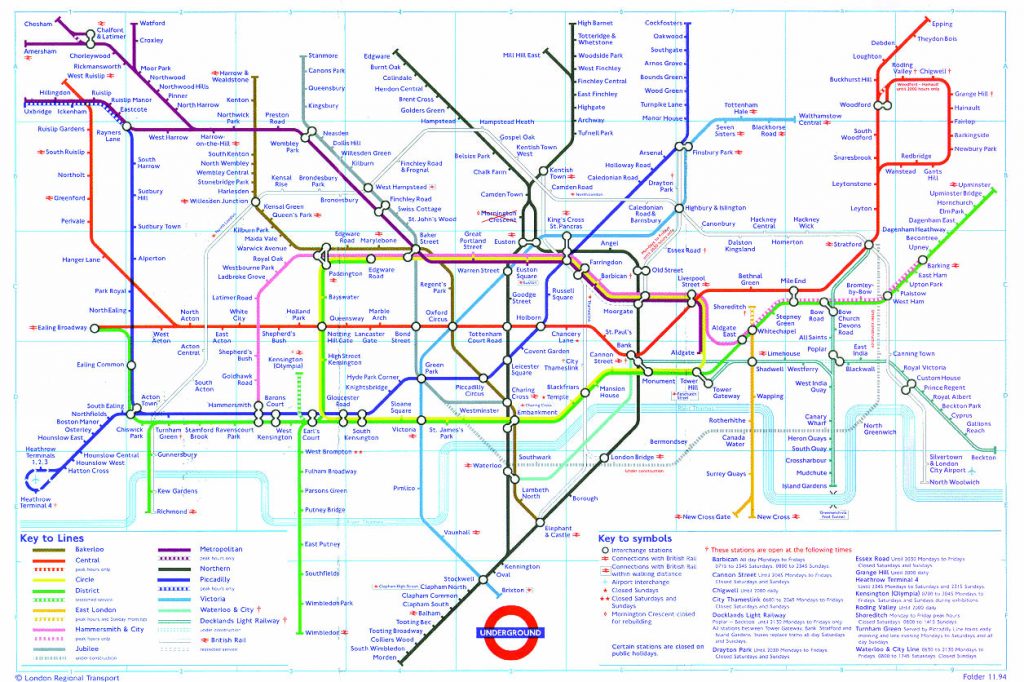

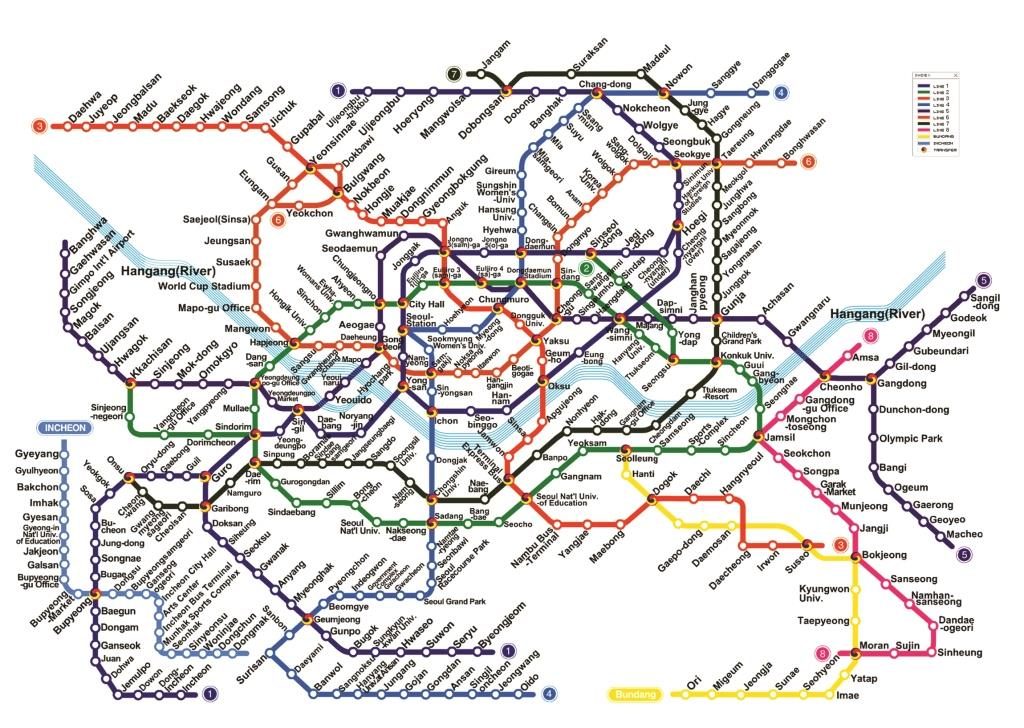

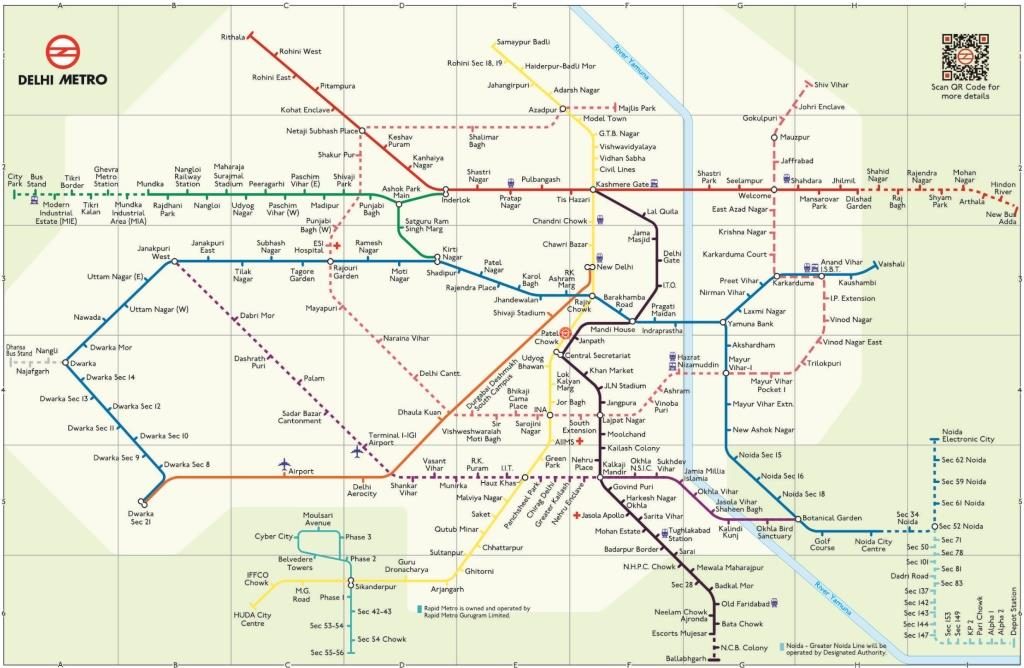

In India, Delhi is the only city that can qualify as a city with well-developed public transport network. However, a look at the Delhi metro map too reveals that there are only fifteen interchange stations across ten lines. A comparison with London, Paris, Singapore, or even Seoul offers a completely different picture — these cities have many more interchange stations.

The proposed Mumbai metro network will have as many as 14 interchange points between the eight lines that are currently under construction – a healthy number to provide seamless travel in all directions. Also, 18 of the metro stations will be coincident/connected with the local train network stations – again providing a seamless travel experience between various modes of transport. The metro stations have also been designed so as to being close to densely populated areas and bus stations all along, with the gap between two stations not exceeding 2km. Despite all these efforts and planning, the Mumbai metro network would still be far behind other global cities and insufficient for the needs of the city. While the metro network is still in its nascent stage, it would definitely help if the authorities take this into consideration while designing the next phases of the metro network.

Line 7 was envisaged more as an afterthought – an attempt by the state government to complete at least one metro line before the next state elections in 2019. The line, parallel to line 2A and to the western line of the suburban railways, runs right over the western express highway (WEH) – connecting the suburbs of Dahisar to Andheri. Since the line runs completely over the WEH, preparation of DPR was relatively easier and so was land acquisition.

The line was inaugurated by the PM Narendra Modi in October 2015, along with line 2A. Lines 2A and 7 will together cost Rs 126bn, for which 40% funding is being secured from JICA. Winners of the three EPC packages for Line 7 (JKumar, NCC, Simplex) were announced in August 2016. Civil works on this line are in full swing and are expected to be completed by 2019. The government hopes to make the line operational by mid 2020 – likely missing the state elections in 2019.

Line 9 has two packages – one 14km overhead route connecting Dahisar to Mira Road and second 7km underground route to connect Andheri station (of line 7) to the international airport. The foundation stones for this line was laid on 18th December 2018 by the PM Narendra Modi. The civil contract winners for these two packages are expected to be announced soon, and construction activity should start late 2019.

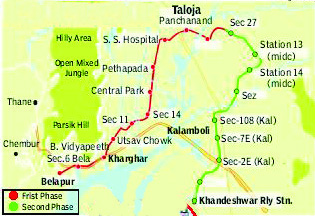

Navi Mumbai Metro is probably the most ill-conceived metro projects in the city. It is designed to connect two far-flung sparsely populated areas of Navi Mumbai with no connectivity to any of the lines of the main Mumbai city and any of its other suburbs. What’s worse is that it comprises of two phases, which will not be connected to each other – a third phase will be needed to connect the two!

Phase 1 of the Navi Mumbai metro, being developed by CIDCO, consists of an 11.1km network, originally estimated to cost Rs 20bn – now escalated to Rs 30.6bn. The foundation stone of the metro was laid in May 2011, with an initial deadline of December 2014. However, multiple hurdles such as clearance from Central Railways for an over-bridge, clearance for extending the height of high tension wires, and heavy traffic on Sion-Panvel Highway meant that the project has faced huge time/cost over-runs. In between, CIDCO terminated the original developer’s (Supreme Infrastructure) contract and appointed a new one. The deadlines were moved – to July 2018, then May 2019, December 2019 to now May 2020. In March 2019, CIDCO procured two metro trains for operations and is confident of meeting the May 2020 deadline.

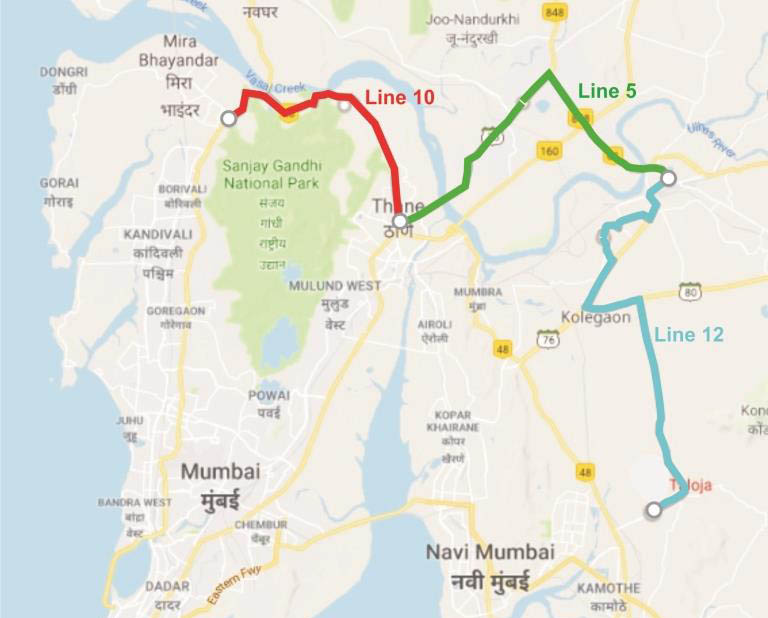

Line 5 connects the suburbs of Thane to Kalyan. The foundation stones for this lines was laid on 18th December 2018 by the PM Narendra Modi. Civil works are expected to be awarded in 2020, after state elections. Construction should start in late 2020 or early 2021.

Lines 10, 11 and 12 are in the pre-awarding stage with DPRs prepared and approved. Order awarding activity is expected to occur early 2021, and construction to start by the end of 2021.

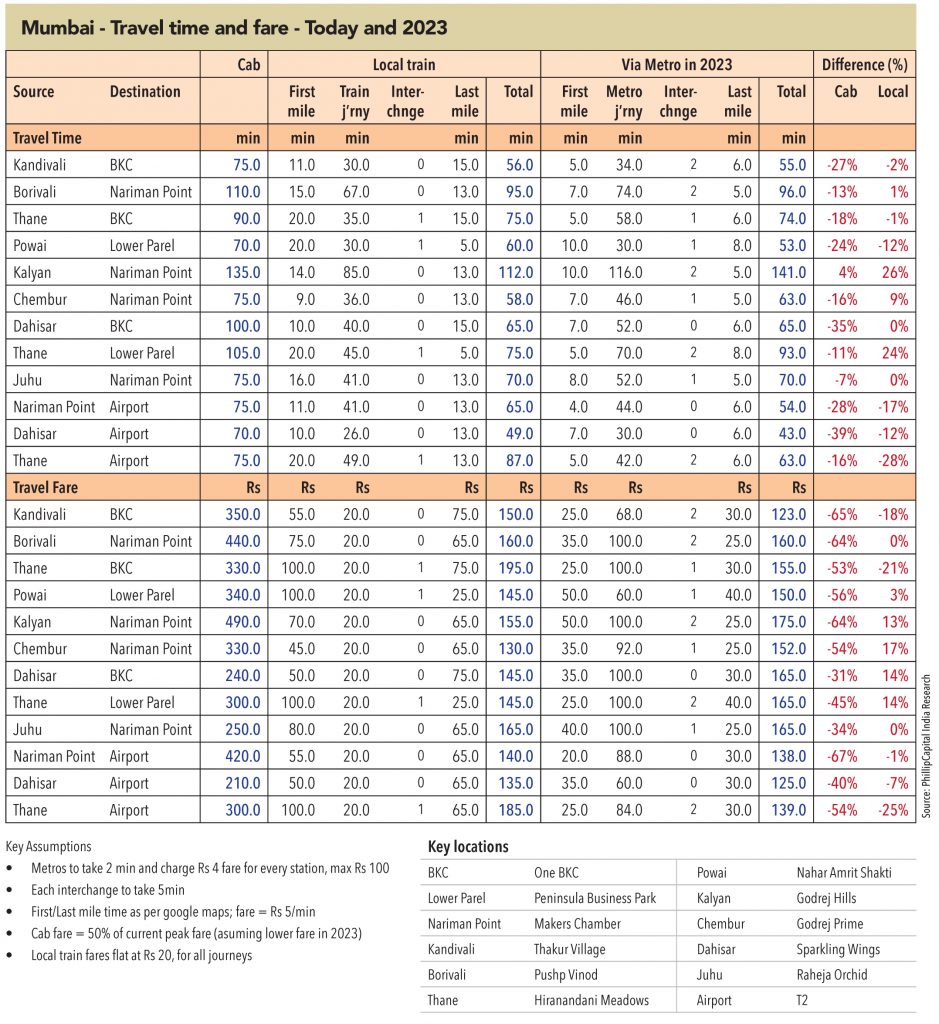

The metro network will go a long way in decongesting the roads and railway network of the city – and also reduce the commute time for residents. GV carried out an exercise to find the commute route, time, and cost for few of the premier locations across the city – especially for people travelling for work. The results show a remarkable reduction in time and cost for the commuters across the city – along with a significantly better travel experience.

With over 160km of lines under construction, the Mumbai metro network will touch 200km by 2023 – this not including the latest 5 lines (5,9,10,11,12) that are yet to be awarded. Authorities expect over 5mn commuters to use the metro network then – far ahead of the current ridership of 2.6mn of Delhi Metro. The current ridership of Line 1 (~400,000) and Monorail (~15,000) remains low due to limited reach of the metro network. In 2023, the metro network of the city, along with its operational local train network, will look like this:

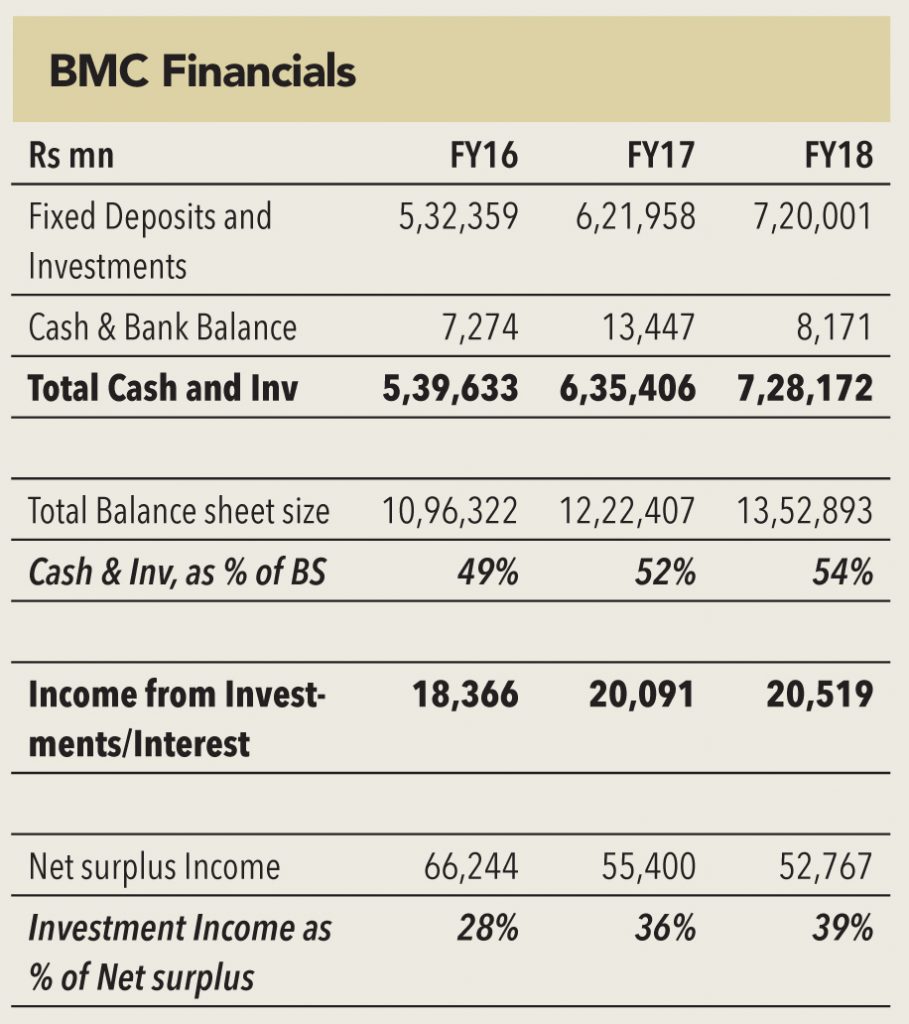

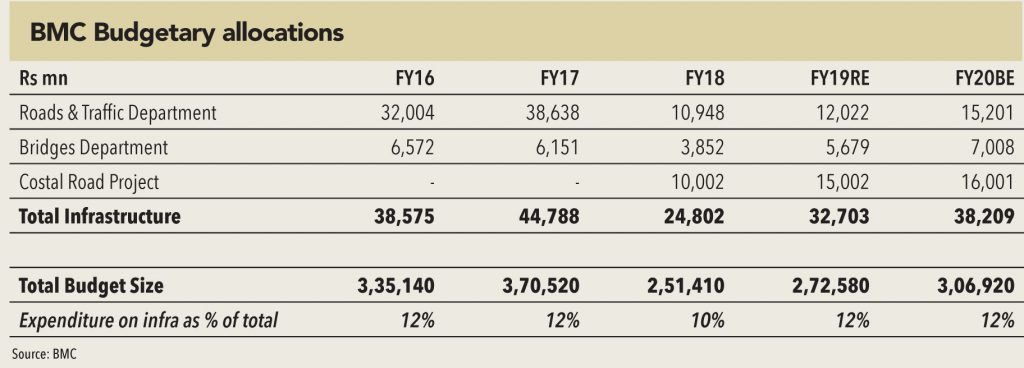

BMC (Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation) is THE richest Municipal Corporations in India and one of the richest across the world. Its FY18 annual report puts its cash and investments (including fixed deposits) at a whopping Rs 728bn (Rs 635bn in FY17) – more than 50% of its balance-sheet size. At a time when most city municipalities around the world are reeling under the pressure of debt taken to finance their infrastructure and other development projects, BMC has a debt of only Rs 3.8bn (Rs 4.5bn in FY17) – just 0.5% of its cash and investments. The corporation earned Rs 20bn as income from investments and interest – accounting for 39% of the net surplus income it generated in FY18.

And yet, BMC spends very little on the development in the city. In FY18, the corporation spent only Rs 15bn on Roads & Traffic and Bridges Department – along with only Rs 10bn allocation for the coastal road project (which never got used). This forms a paltry 10% of its overall budget expenditure of Rs 251bn. However, off late, the municipal body has loosened its purse string, and has agreed to fund large projects like Mumbai Coastal Road (Rs 130bn) and Goregaon Mulund Link Road (Rs 40bn) – on top of the regular road expansion and maintenance work it executes.

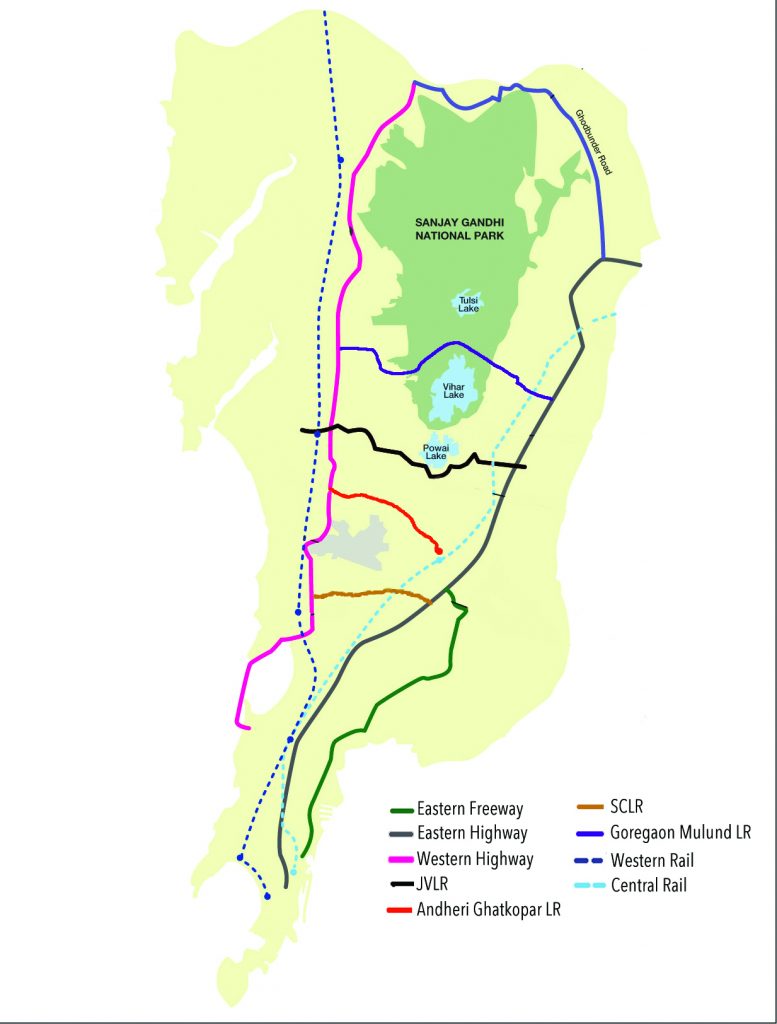

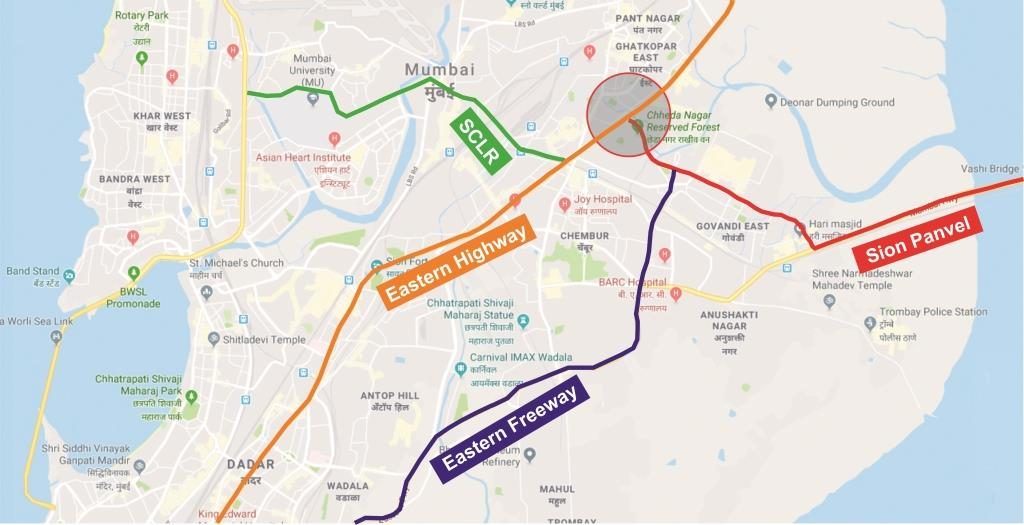

The primary problem in designing transportation infrastructure in a city like Mumbai is its longitudinal structure. The city, originally formed in the shape of a peninsula has only expanded towards the North – with sea covering it on the eastern and western sides. While attempts have been made to attract the population to move to eastern suburbs like Navi Mumbai and Vashi – the migration has been much below the authorities’ expectations and the city’s requirements. Hence, most transportation projects in the city, historically, have been designed to provide North-South connectivity.

1) The two main suburban railways lines are – Western (Virar-Churchgate) and Central (Badlapur-CST)

2) Three main expressways are – Western (WEH), Eastern (EEH) and Eastern Freeway (EFW)

The primary problem in designing transportation infrastructure in a city like Mumbai is its longitudinal structure. The city, originally formed in the shape of a peninsula has only expanded towards the North – with sea covering it on the eastern and western sides. While attempts have been made to attract the population to move to eastern suburbs like Navi Mumbai and Vashi – the migration has been much below the authorities’ expectations and the city’s requirements. Hence, most transportation projects in the city, historically, have been designed to provide North-South connectivity.

1) The two main suburban railways lines are – Western (Virar-Churchgate) and Central (Badlapur-CST)

2) Three main expressways are – Western (WEH), Eastern (EEH) and Eastern Freeway (EFW)

SCLR Phase 2

In 2010, Roberto Zagha, the World Bank’s India head, referred to SantaCruz-Chembur-Link-Road (SCLR) as the ‘world’s most delayed road project’. Conceived in 2003, the project, which provides connectivity between the eastern and western suburbs of the city, took eleven year to complete. So desperate was the government to commission the project before 2014 elections, that the road was thrown open to the public without many of the supporting iron pillars and structures removed. Nonetheless, the road has significantly reduced the travel time between Chembur and Santacruz (from 60 minutes to just 10 minutes). The project also boasts of the first double-decker flyover in the city (second in the country).

The SCLR is part of the MMRDA’s plan to improve horizontal connectivity in the city. As an extension of this, MMRDA has already awarded contracts for Phase 2 of the projects (SCLR-2) – which connects the suburb of Kalina (where the SCLR-1 ends) to WEH. This would provide an end-to-end connectivity between EEH and WEH – aiding the JVLR in catering to horizontal movement of traffic across the city’s landscape. The civil contracts for this project were awarded to JKumar in 2017 and it is expected to be completed by 2020.

Ghatkopar-Mankhurd Link road

This road serves as one of the only two roads connecting the eastern/western suburbs and the island city to the suburbs of Navi Mumbai. A large number of heavy vehicles enter and leave the city through the Navi Mumbai suburbs, making this road perennially congested. In order to decongest it, MMRDA has awarded the contract to expand the 4.5km long road and build a 2km flyover over it – thus facilitating swift movement of traffic. The flyover will enhance connectivity to Eastern Freeway and SCLR.

The civil contracts for this project were awarded to JMC Projects in December 2016, and it is expected to be completed by July 2020.

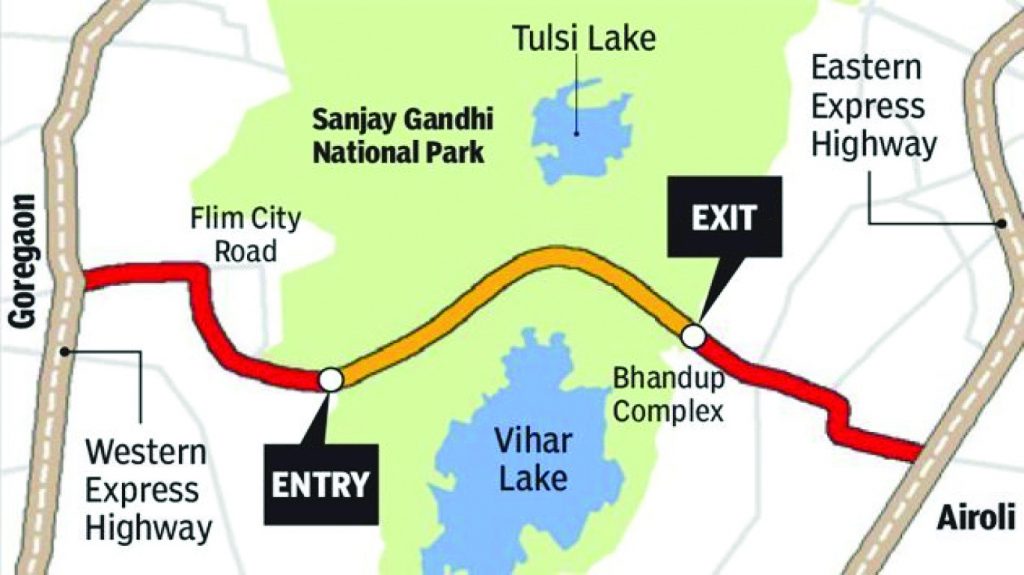

Goregaon Mulund Link Road (GMLR)

This has been one of the most controversial projects in the city because it was to pass through one of the iconic green reserves of the city – the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. After much deliberation, negotiations, and adjustments, this project, which was recommended in 1963, is now in its final stages and should see tenders floating soon. The 14km, Rs 38.5bn project, is to comprise of three flyovers, an underpass, a rotary, and a 5km, six-lane box tunnel under the Sanjay Gandhi National Park – between Film City (Goregaon) and Bhandup. Once completed, it will reduce the travel time between the two places to 15-20 minutes from the current 1 hour 10 minutes.

The project received a nod from the National Board for Wildlife (NBW) in February 2019, and awaiting for forest clearance. While the BMC has made a provision of only Rs 1bn in its FY20 budget, more funds will be provided in FY21 and beyond – when the project starts execution. Civil contracts are expected to be awarded in mid 2020, and the link should be operational by 2024.

Chheda Nagar flyover

This flyover would not have been necessary for another 20 years, were it not for the meticulous planning (or actually the lack of it) by the authorities. Read our special section (How a new bottleneck was miraculously ‘created’ at Chheda Nagar) to find out more about how and when the need for this flyover arose. This section focuses on the fact that three major roads (EFW, SCLR, and EEH) merge at the now famous Chheda Nagar junction – leading to long queues of vehicles and long waiting times. To decongest this, the MMRDA has designed a three flyover structure, that will help serve the needs of commuters heading in almost all directions.

The Chheda nagar flyover structure will consist of three flyovers:

1) 680m-long 3-lane flyover on the junction on the Sion-Thane stretch.

2) 1,235m-long 2-lane flyover connecting Mankhurd road to Thane directly

3) 638m-long Chheda Nagar flyover to directly connect motorists to SCLR

The project is expected to cost Rs 2.24bn, and the civil contracts were awarded to JKumar in May-2018. The project is expected to be completed by 2021.

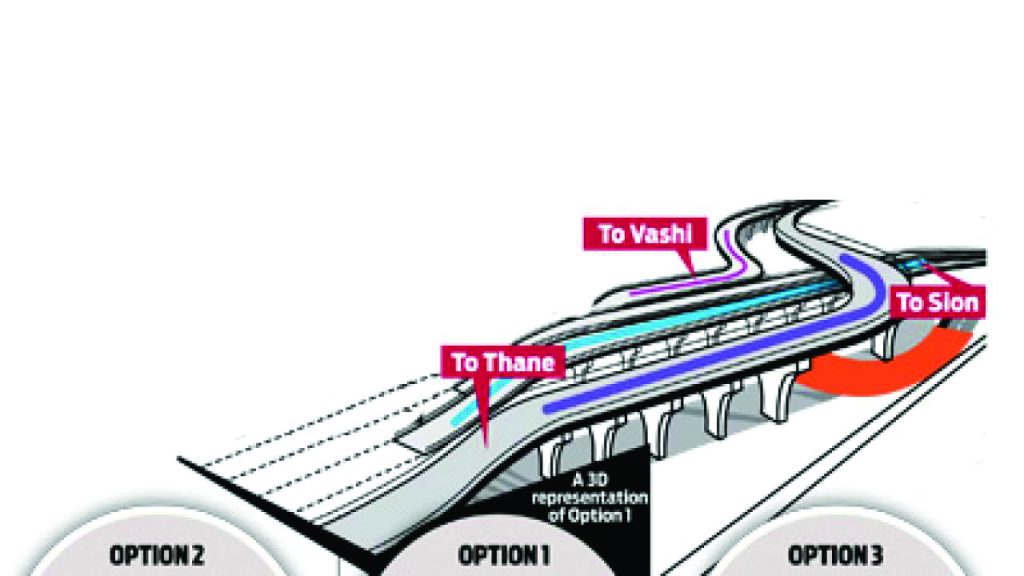

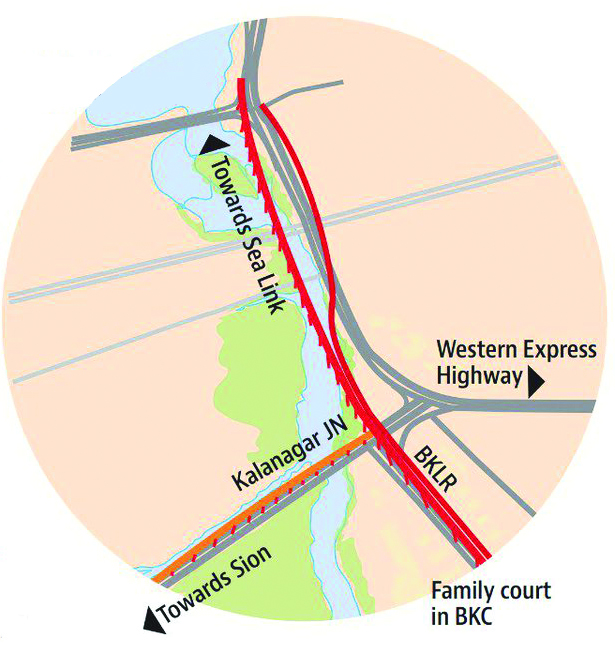

BKC-Sion and Kalanagar flyovers

These flyovers are part of an elaborate scheme to enhance connectivity to BKC – the area which the MMRDA wishes to transform into the city’s CBD (it already is, for all practical purposes). The twin flyovers, along with the SCLR-2, are to provide a ring-road structure to BKC – enhancing its connectivity to WEH and EEH. The Kalanagar flyover will also provide speedy access to BKC for commuters plying to and from the BWSL and the proposed coastal road.

The proposed BKC-Sion flyover starts from G-Block of BKC – and after crossing the Mithi River, LBS Marg, Central and Harbour Railway tracks, and Somaiya Trust Groundit joins the EEH. The civil contracts for this project were awarded to JKumar in August 2016, and it is expected to be completed by December 2019.

The proposed Kalanagar flyovers includes: (1) a 900m flyover connecting BKC to BWSL, and (2) 450m flyover connecting Sion T-Junction at Dharavi to BWSL. The civil contracts for this project were awarded to Simplex Infrastructure in September 2016. The project was expected to be completed by June 2019 – now expected to be completed by December 2020.

The key achievements of these projects will be to enhance the longitudinal (East-West) connectivity across the city. After the completion of SCLR-2, GMLR, and MTHL (discussed in the next section) – there will be as many as six links providing east-west connectivity at different points in the city (as compared to three currently) – thereby, significantly easing the load on the current road network. When will these road projects be complete? Would the traffic not have grown by then and would that not reduce the impact of these projects? These are questions we all know the answer to!

Five years ago, Chheda Nagar was an obscure unknown name in this city – 8 out of 10 people would not have heard about this place, and those who had, would have vouched for its insignificance in the larger scheme of things. But today, majority of people with offices in BKC or Nairman Point would be aware of this place, especially people residing in the central and Navi Mumbai suburbs. The credit for making this place famous (or rather infamous) goes to the city’s authorities.

Between January and December 2014, the authorities completed and threw open to public two ‘mega’ road projects that were being developed for almost a decade (conceived many decades ago) – The Eastern Freeway (EFW) and the SantaCruz-Chembur-Link-Road (SCLR). The two were supposed to enhance the connectivity of the two prime CBDs – BKC and Nariman Point – to the central and Navi Mumbai suburbs. They actually succeeded in doing that – as depicted by the large number of vehicles that adopted these new routes as soon as they were thrown open. But little did the commuters know, that the two roads had succeeded in creating a new bottleneck in the city that did not exist before – the Chheda Nagar junction (CNJ).

The EFW, connecting the island city (from P D’mello Road) to the suburbs (Mankhurd) – connects to the Eastern Expressway at the CNJ. And to travel in three of the four directions from the end point of the Freeway – commuters have to cross the CNJ. Similarly, the SCLR also connects the BKC to the Eastern Expressway at the CNJ. And again, to travel in three of the four directions from the end point of the SCLR – commuters have to cross the CNJ. On top of that, CNJ has its own existing captive traffic of the Eastern Expressway – for people travelling to Eastern/Western/Navi-Mumbai suburbs. Hence CNJ became the junction for people travelling in three of the four directions from any of the three critical roads of the city.

The result, which any basic traffic simulation exercise would have forecasted (if one was ever undertaken), was a huge pile-up of vehicles at the CNJ. The traffic police were caught unawares, and weren’t able to comprehend what happened! For the last five years, CNJ has become one of the longest traffic signals in the city, with the long queue of vehicles in all directions. Mumbai development authorities might not be able to build perfect roads, but they do know how to create perfect bottlenecks.

It took MMRDA three years to design a solution to decongest the CNJ, which, as usual, went through its own set of corrections and delays and was finally awarded to a contractor in 2017. The flyover – a three legged one – is expected to be completed by 2020 – and will help commuters finally breathe a sigh of relief – after six years of the most frustrating waits.

While the CNJ might be de-bottlnecked in sometime, the problem is symptomatic of a bigger malaise that has set in – no planning or estimation of the impact of a project being conceived. It is as reactive a planning as it can be – trying to find solutions AFTER the problem has been created. In a city as vast as Mumbai in which little has been done over the last two decades and a lot is being done right now, proper planning and co-ordination is required between various authorities to ensure minimum wastage of public resources and maximum benefit to the residents.

If there is one image that you’d see across media (print, electronic, social) that represents the city of Mumbai – it is the iconic Bandra Worli Sealink. Built at the whopping cost of Rs 16bn, the project enhanced the connectivity of the western suburbs to the island city, and eliminated 23 traffic stops in the process. The link was thrown open to public in 2009, and has had a significant impact in reducing commute time across the city.

However, much like most other projects in the city, this one too was completed in haste and abandoned without actually being completed. In our earlier GV on Mumbai infra, we called it an ‘Engineering disaster-piece’ for the simple reason that it constituted a 4.7km-long sea-link culminating in a right-angle connection to the main road – defying basic principles of civil engineering. Also, the link was earlier envisaged to be extended up to Haji-Ali in the south and Versova in the north – but no action happened on either for a long time.

Eventually, in 2018, the Worli-Nariman Point link and the Bandra-versova sea-link were included as parts of an ambitious mega project – The Coastal Road. A little earlier, in 2017, the government was finally able to tie-up funding for the Mumbai Trans Harbour Link (MTHL) and was able to award its civil contracts, after multiple attempts, on EPC/PPP basis. These two ‘special projects’, when complete, would not only enhance the suburban connectivity across the city, but also add to the list of iconic structures the city can boast of.

This project could enter into the Guinness Book of World records as ‘the project with the most number of unsuccessful attempts at being awarded’. The first attempt to award this project was made in 2004. Thereafter, after six failed attempts (initially on BOT, later on EPC basis) the project, divided into 3 packages, was awarded to 3 consortiums in November 2017. Construction activity started in April 2018, and is expected to be complete by late 2022. The awarding body, MMRDA, expects more than 70,000 vehicles to use the bridge daily, after commissioning.

MTHL is a 21.8km-long, 6-lane, freeway-grade road bridge that would include a 16.5km-long sea bridge and 5.5km of viaducts on land on either end of the bridge. About 4km of the bridge length is being built with steel spans to eliminate the need for pillars (which could have hindered the movement of ships in the area). The link will connect the island city with Navi Mumbai – starting at Sewri (South Mumbai) and across Thane Creek (north of Elephanta Island), to terminate at Chirle village (Nhava Sheva).

MTHL will directly connect the island city to the suburbs of Navi Mumbai, and also, serve as a key road, connecting the under-construction Navi Mumbai International airport.

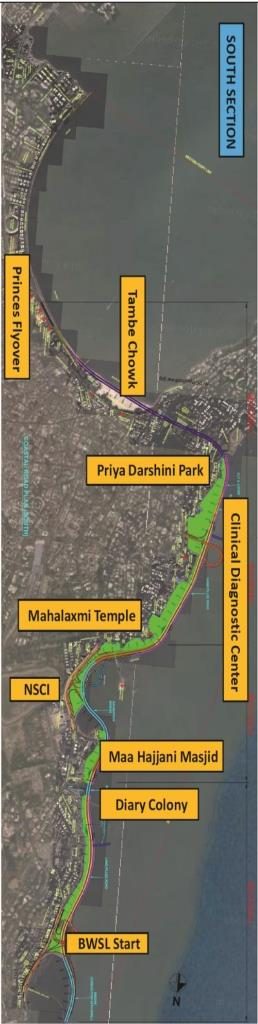

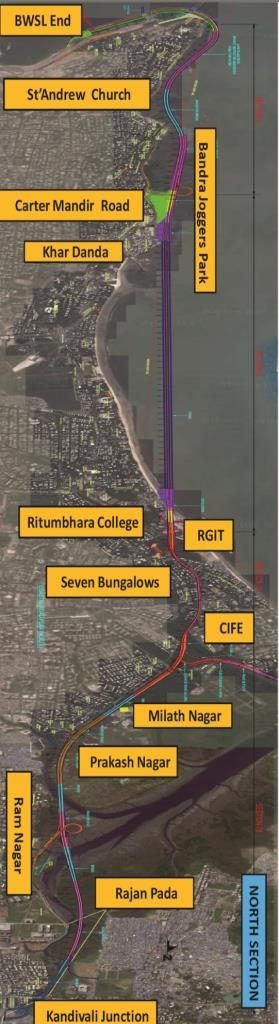

The highly ambitious and picturesque 8-lane, 29.2-km-long freeway, that would run along Mumbai’s western coastline – providing beautiful views of the ocean, while enhancing connectivity and decongesting traffic in the city – has been one of the most controversial projects in the city. Over the last 18 months, various NGOs and environmentalists have opposed the project for its negative impact on the environment.

The coastal road will connect Marine Lines (in the island city) to Kandivali (northern suburb). From its initial plan of just being a bypass route, the project plan had undergone radical transformation, to become an 8-lane multi-modal transport route with bridges, BRTS corridors, a 3.4-km tunnel (from Khar Danda to Juhu) and interchanges at various locations like Haji Ali, Worli, Breach Candy Hospital and Bandra. Public spaces such as cycle tracks, promenades, pedestrian underpass or foot overbridges are planned at every 500 metres, along with advanced parking facilities and recreational zones.

The Coastal Road is projected to be used by 130,000 vehicles daily and is expected to reduce travel time between South Mumbai and the Western Suburbs from 2 hours to 40 minutes.

Two sections, adding upto 13.8km of the Coastal Road project, have been awarded. The remaining stretches were earlier expected to be awarded in 2020 – after the state elections in 2019. But as recently as 16th July 2019, the Bombay High Court has quashed the CRZ clearance granted to the project – as the project falls under a development project and not a road project. This would now require consultations with various stakeholders, including NGOs that have been vehemently opposing the project. These current and future hurdles might take this project well beyond its targeted deadline of 2023.

The island city is famous for a lot of things – the iconic Gateway and the Sea-link, the old heritage buildings, the film industry, cricket, being the finance capital of the country, safety of women, slums, crumbling infrastructure, and being the political centre of the state. But it also figures in many record books that it would not be really proud of – it boasts of some of the most delayed projects in the World! In 2010, Roberto Zagha, the World Bank’s India head, referred to SCLR as the ‘world’s most delayed road project’ – and he wasn’t far from the truth – it took the road 11 years from conception to completion!

Most of Mumbai’s infrastructure projects have the same story – conceived sometime in the last century – taken up in this one – and getting delayed by 5-7 years due to permissions and various other factors. Projects like the EFW, MTHL, SCLR and JVLR were conceived in 1963, and have all started operations only in the 21st century – some are yet to start operations. There are chiefly two problems:

1) Multiplicity of authorities: MMRDA, MSRDC, and BMC are three bodies who rarely talk to each other and are all responsible for the infrastructure of the city. The result is when BMC is developing a flyover, MMRDA is planning a metro over it – eventually leading to both projects getting stalled.

2) Reactive thinking: For long, infrastructure projects in Mumbai (and in the state of Maharashtra) have all been reactive – deciding to build a road/flyover/metro/airport – when its need is fully evident and screaming in the face. The projects are then hastily put together and executed. The result is that most infrastructure projects end up serving the needs of the last decade – and are hardly ever futuristic.

What do the Eastern Freeway, MTHL, JVLR, SCLR, and Coastal Road have in common? A cool fact – that all these projects were initially conceived in 1963 – and that it took the first among them, over 40 years to become operational (JVLR).

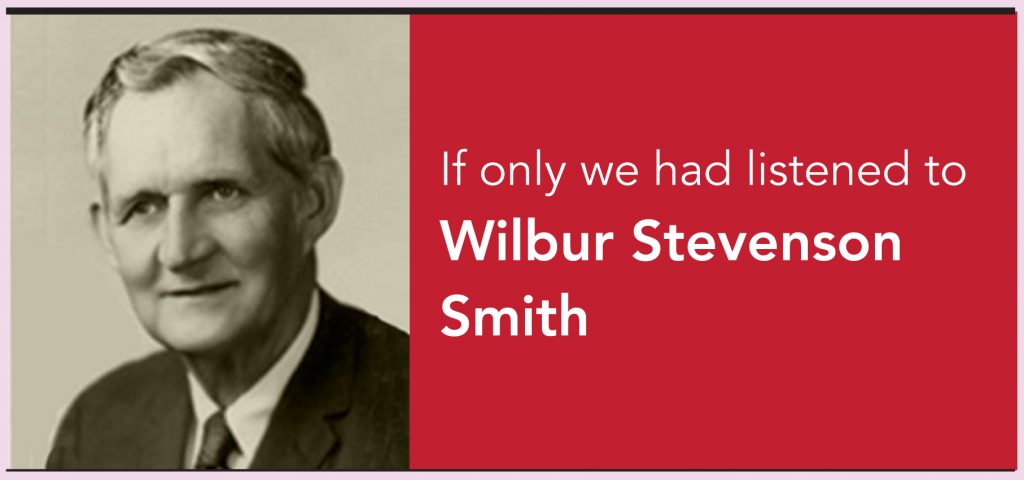

In mid-1962, the Central planning Commission had appointed M/s. Wilbur Smith and Associates to prepare a report on Urban Transport Project for Traffic Planning in Mumbai. The company, started by Wilbur Stevenson Smith (a graduate from the University of South Carolina, studied traffic engineering at Harvard and Yale), completed the report in 18 months and submitted the same in December 1963. The report included theoretical studies on the existing road network, on-ground surveys of car occupancy, vehicle trip and pedestrian count, at select locations. The report recommended at least 10 freeways and expressway, and 24 major arterial roads across the city. Alas, even today, only few of them are operational – more than half a century after it was submitted.

Some of the key projects that the report had recommended have taken the form of JVLR, SCLR, and Eastern Freeway. Few of its recommendations like Coastal Road and MTHL are still being implemented. The plan also envisaged a CBD (of the size of BKC) in Uran (Navi Mumbai) – which would have been connected by the MTHL to the island city – a step which would have helped the city grow eastwards, rather than northwards. Most shockingly, the cost of implementations of Smith’s plan, at that time, was a paltry Rs 960mn. Even if it is compounded at 10% annual, its cost today would have been Rs 181bn – compared to that, today the cost of MTHL alone is Rs 140bn and the Coastal Road is Rs 130bn!

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access