Structural drivers are supporting growth, despite near-term challenges

India’s core advantages of higher topographical diversity, soil, and climate makes it one of the most agriculture-conducive countries in the world. The small-sized farming, different cropping patterns across the country and farmers’ multi-tasking ability makes India a leader in agriculture. However, farming has also become challenging over the past few years due to mismanagement of resources, policies, and climate change. “There is no doubt that agriculture is the prime driving force of rural India. While the last few years have been challenging for farmers, the government’s current focus towards farming will surely support them. In fact, this has helped us to grow faster in terms of revenue and profit,” said Mr Shinde, a product development manager with a large fertiliser company based in Pune, speaking to the GV team at a Kisan Fair.

Despite all its inherent positives, it is fairly well known that Indian farming and its farmers are facing many challenges; a key one is earning reasonable profits or recovering costs. Dr Ashok Dalwai, CEO of Doubling Farmers Income Committee of Government of India, believes that there are problems on both sides – production and post production. “The first is addressed via high MSPs and the second via marketing efforts. Some changes are visible, but it will take time,” he said. Mr Dalwai’s comments are in line with the government’s efforts to encourage better agriculture growth and its approach of making structural changes in the sector.

“We (farmers) are also businesspersons – we shift to crops where returns are higher. Also, we gauge water availability, MSP, and mandi prices before sowing,” – Mr Rai, a farmer and agriculture inputs dealer in Amritsar, Punjab.

Here are some of the structural changes that are panning out in the sector:

One of the main disadvantages of Indian farming has been dependence on monsoon water. In the past two decades, we have seen that every 2-3 years, there has been a drought-like situation or below-normal rainfall compared to periods in the 1980s or 1990s, which were more stable. As uncertainty of monsoons often puts sowing and crop-production at risk, farmers need to find options to improve production and yields. Focussing on less water-dependent crops is an ideal option.

The government has been advising farmers to select crops with minimum water requirements. “I am planting more oilseeds (soybean) rather than wheat and rice over the past two years, as water availability is very limited,” said a farmer from Latur, Maharashtra, who seemed quite satisfied with this gradual shift in his sowing pattern, which he believed has helped him improve yields and realisations.

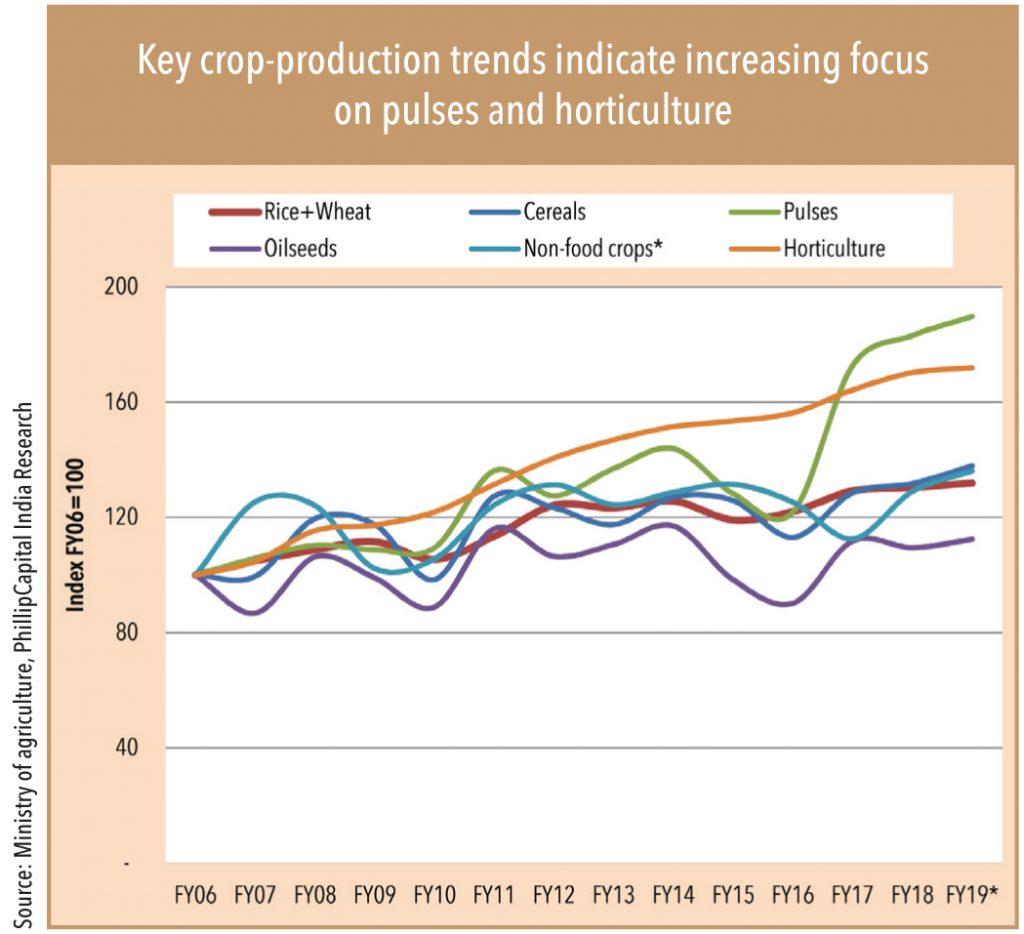

Mr Darak, a senior marketing representative of Hifield-AG Chem India, a small agrochemicals company based out of Aurangabad believes that fruits, vegetables, and cereals are the best options for farmers. “Water plays an important role in farming; deficient rainfall over the past two years forced farmers to adopt different cropping patterns requiring less water.” Historically, farmers have been quite inclined towards sticking to traditional crops due to well-known procedures in terms of sowing, costs, realisations, and credit management. Often, farmers only stick to crops sown by neighbouring farmers so that profits/losses are similar. However, as Mr Darak points out, – “Now, farmers are more aware of newer products, methods, and crops. They are happy to take up new challenges. One more reason for accepting change is the uncertainty of rainfall – farmers have to find some solution if rainfall is not great.”

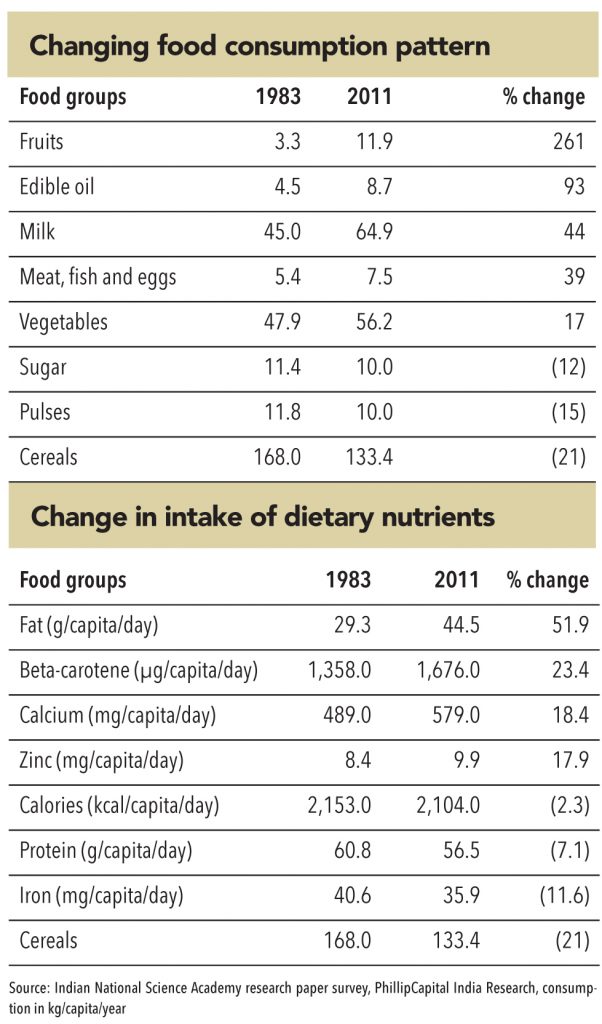

Many agencies are expecting India’s population to be c.1.8bn by 2050, which would entail a c.70% rise in food demand. In addition, rising income levels of the middle-class population is supporting changing food-consumption patterns. People are moving towards animal products (poultry, meat, and eggs), fruits, and vegetables vs. cereals earlier.

Kisan Fair, India’s largest agri show, saw 150,000 agriculturists and over 500 companies attending in 2019. At the event, the main reasons for changing food consumption patterns emerged as alterations in lifestyle and eating habits. Many agriculture inputs companies emphasized at the Kisan Fair that demand for horticulture, livestock, and fisheries products should overtake cereals (rice, wheat) demand in the medium to long term. A research paper published by IARI (Indian Agriculture Research Institute) supports this contention. The paper says that from 1983 to 2011, consumption of cereals declined by 21% – from 168kg to 133kg per capita per year. In the same period, consumption of milk increased by 44%, meat by 40%, fruits by a whopping 260%, vegetables by 17%, and edible oils by 79%.

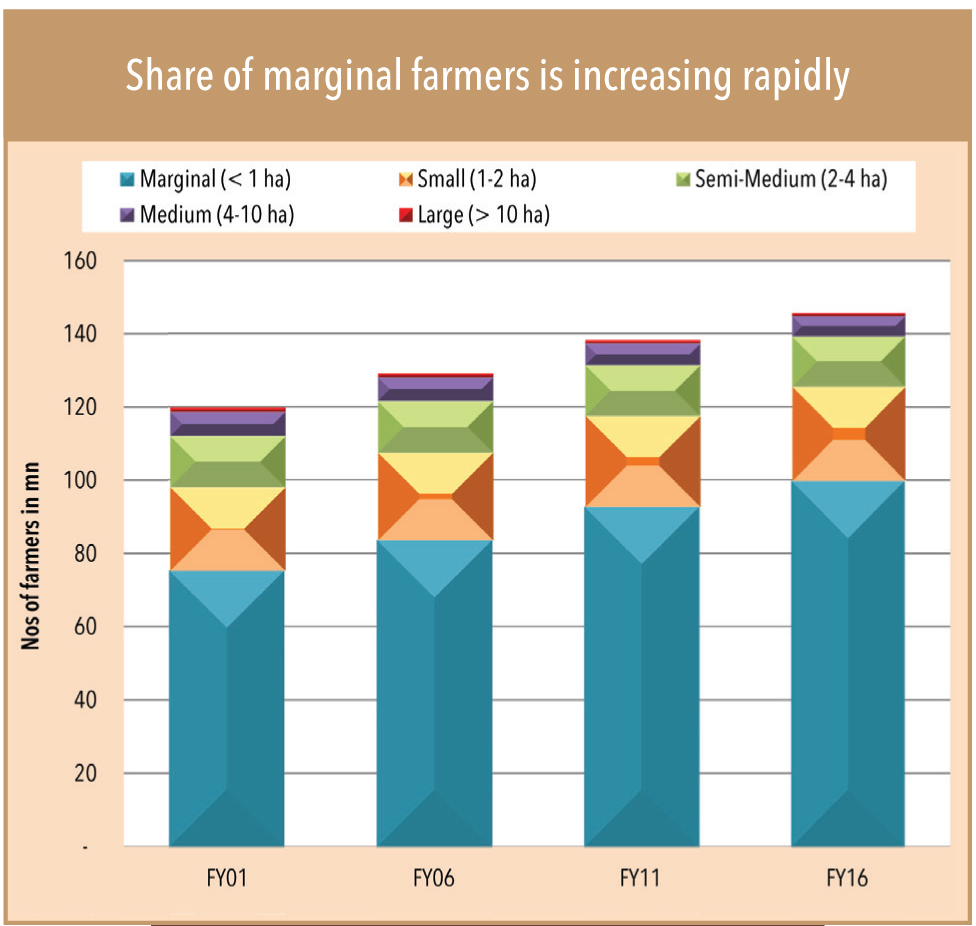

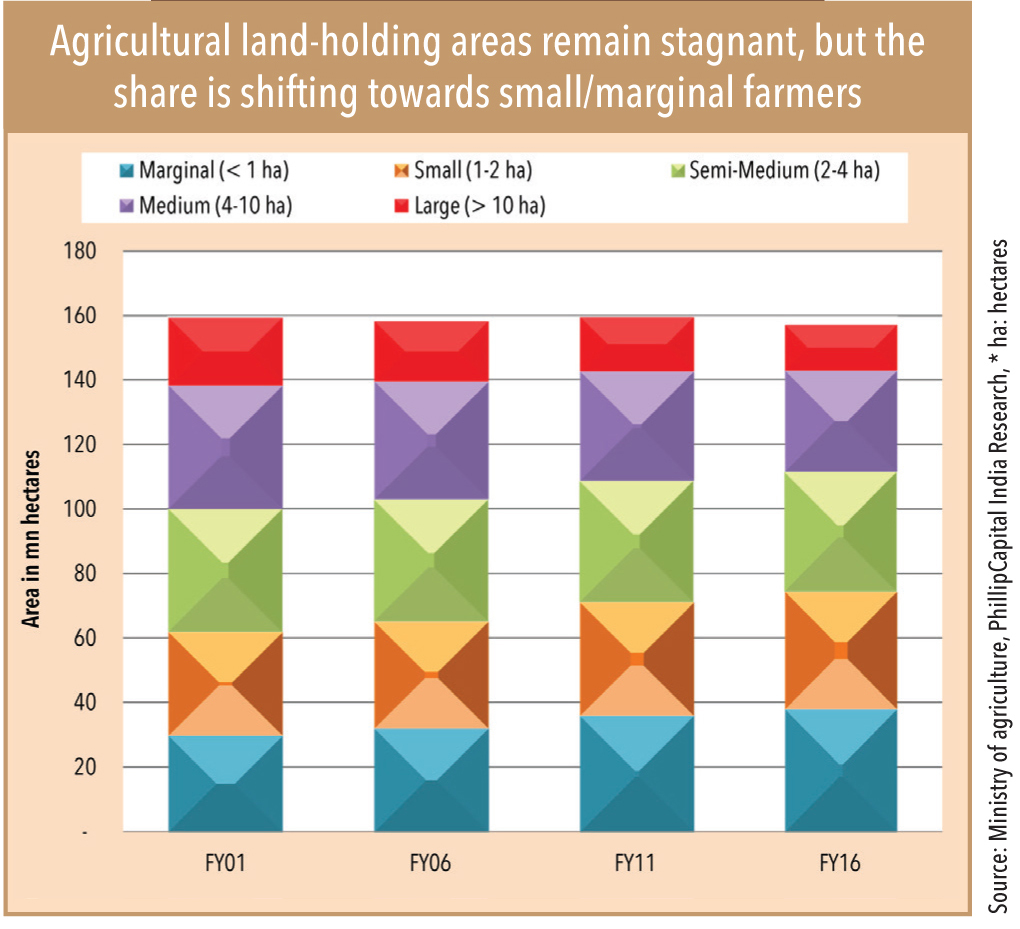

While India’s agricultural land mass has remained stagnant over the past few decades, share of small and marginal farmers’ holdings (<2 hectares) is continuously rising. By 2016, their share was c.90%; therefore, government policies and reforms are formed keeping the interest of these farmers in mind.

“Inheritance issues have led to division of land holdings into smaller and smaller holdings,” said Mr Nimbalkar, a farmer from Nashik, Maharashtra, who holds c.4 acres of inherited agricultural land. Another farmer from Nagpur, Mr Kamble, who has about 2 acres, believes that smaller holdings support non-traditional crops such as fruits and vegetables and sometimes even oilseeds, better than traditional crops do. “Profits are much better in fruits and vegetables compared to rice, wheat or sugarcane. In fact, I am exporting fruits such as grapes to generate better returns,” said Mr Kamble

The government support has always been important for the development of agriculture. However, the government has limited ability to procure crops and this becomes very important when MSPs falls below mandi prices. In this situation, farmers end up making lower realisations. They have only a limited window to offload their produce and prepare for the next season. Traditionally, the government’s share of procurement is just about 25%, and that too in rice and wheat. That means that farmers have no choice but to sell at mandi prices.

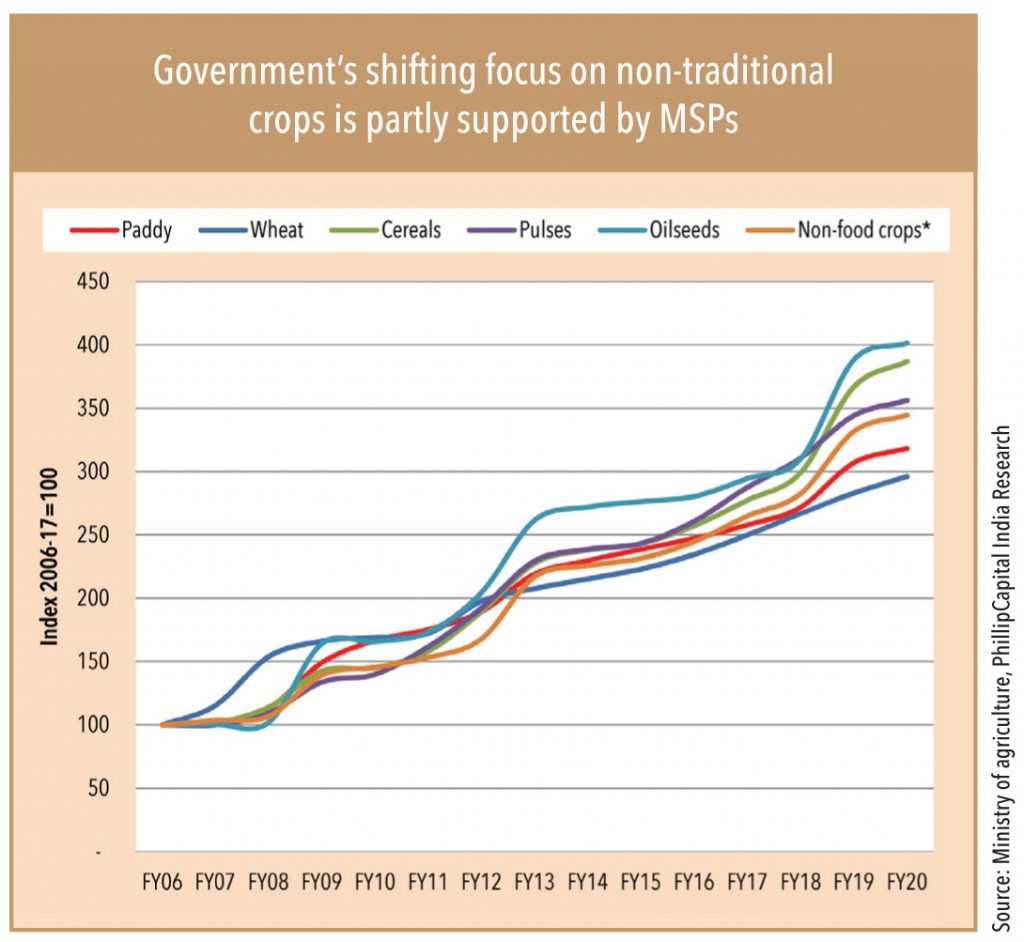

“Government only focuses on traditional crops, as those are essential items for food security. Majority of procurement happens in Punjab and Haryana because both states have better storage facilities,” said Mr Verma, a large distributor of agriculture inputs in Uttar Pradesh. Farmers end up selling at mandi prices in most states. “Over-supply of rice/wheat has forced the government to encourage cereals/pulses/oilseeds by raising MSPs, so that farmers receive better returns,” he added. MSPs trends over the past few years support this shift.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access