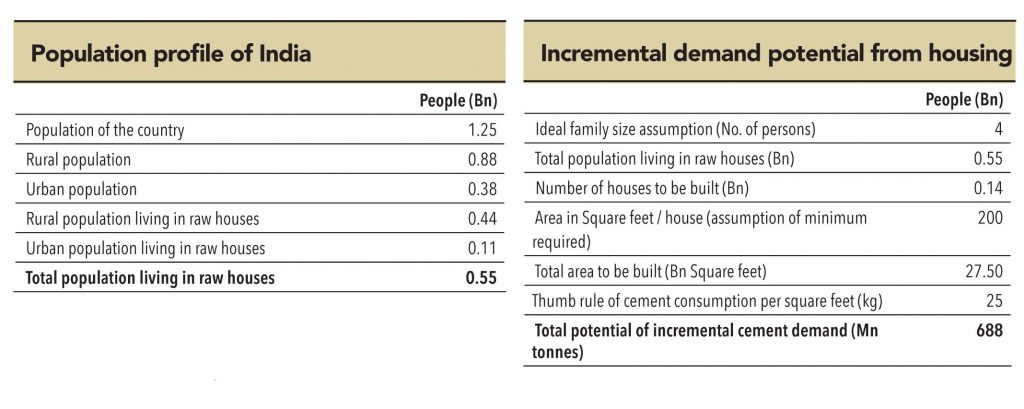

Demand from housing will remain the primary driver: Currently, more than 50% of India’s rural population and more than 30% of its urban population do not have access to cement (pucca) houses. It is unfair to assume that all of these houses will be built in the next 10-15 years. However, even if a part of this is executed, the potential for cement demand can be huge. Narendra Modi has a vision to provide housing for all by the end of 2022. An indicative calculation of the potential of cement demand that can initiate from housing is as follows:

Assuming housing-for-all and only minimum square feet construction (200 square feet, just the size of a room), nearly 700mn tonnes of incremental cement demand is possible. However, this seems an impossible number to achieve in the foreseeable future. If the government sets its heart on achieving this, say over the next 20 years, housing alone can trigger cement demand growth of 8-10% every year.

Announcements in mass-housing schemes are likely to happen soon. Few notable state-housing schemes are in the annexure. Within state housing schemes, Haryana has the maximum number — this explains the increasing interest of cement manufacturers in catering to this region. Most major housing schemes in progress are in the North, East and West. South India is yet to see any new major housing scheme announcements. However, South should see demand revival within 12-18 months, especially with the creation of new state, capital, cities, infrastructure etc.

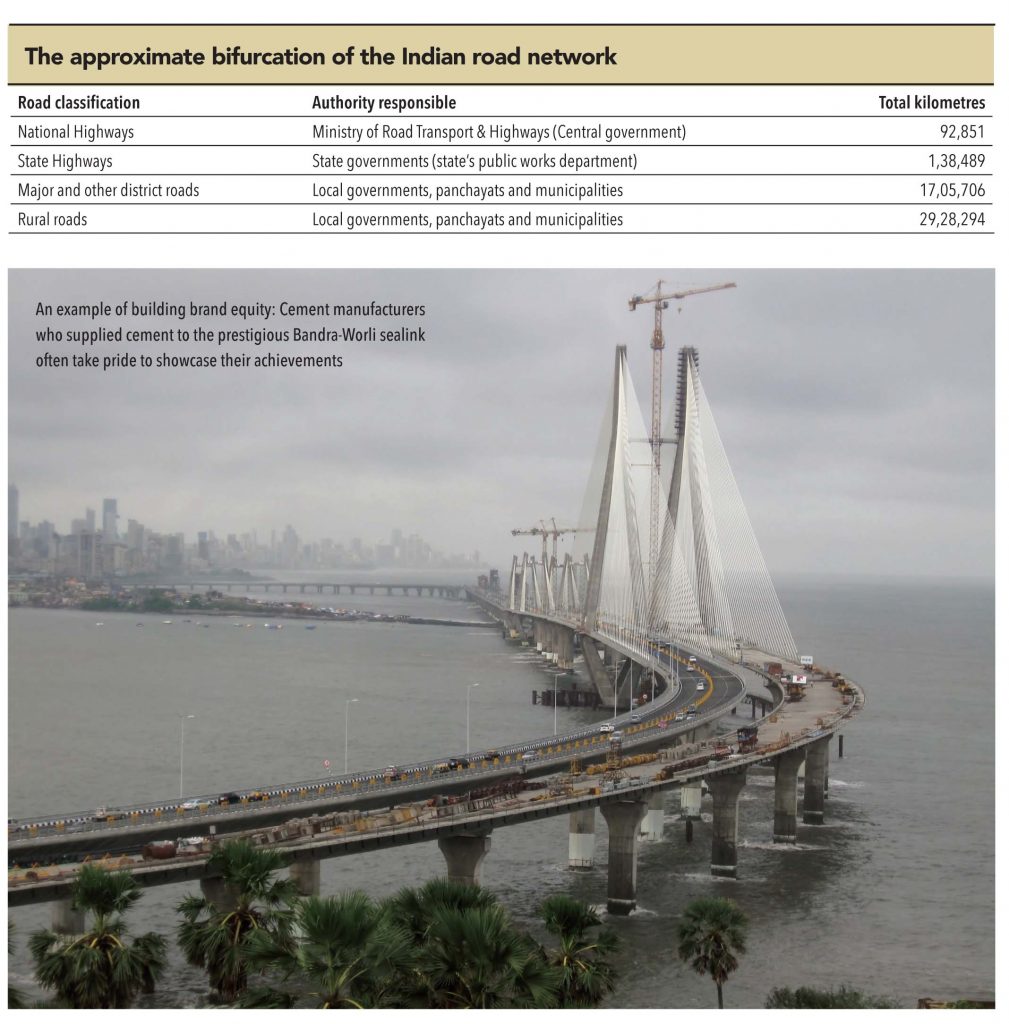

India has a road network of around 4.8mn kms. Of this, only about 54% is believed to be paved. Adjusted for its large population, India has less than 3.8 kilometres of roads per 1,000 people, including all its paved and unpaved roads. In terms of quality (all-season, 4-or-more-lane highways), India has less than 0.07 kilometres of highways per 1,000 people as of 2010. These are some of the lowest road and highway densities in the world.

United States has 21 kilometres of roads per 1,000 people, while France about 15 kilometres – predominantly paved and high-quality in both cases. In terms of all-season, 4-or-more-lane highways, developed countries’ highway density per 1,000 people is more than 15 times vs. India. As of April 2014, India had completed and started using over 22,400 kilometres of recently-built 4-lane or 6-lane highways connecting many of its major manufacturing, commercial and cultural centres.

The rate of new highway construction across India accelerated after 1999, but has slowed in recent years. Policy delays and regulatory blocks reduced the rate of awards to just 500 kilometres of new road projects in 2013. Major projects are being implemented under the National Highways Development Project, a government initiative. Private builders and highway operators are also implementing major projects-for example, the Yamuna Expressway between Delhi and Agra was completed ahead of schedule and within budget; however, the Kundli–Manesar–Palwal Expressway started in 2006 is far behind schedule, over budget, and incomplete.

According to some estimates, India will need to invest US$ 1.7tn on infrastructure projects before 2020 to meet its economic needs, a part of which would go to upgrading its road network. The government is attempting to promote foreign investment in road projects. Foreign participation in Indian road network construction has attracted 45 international contractors and 40 design/engineering consultants, with Malaysia, South Korea, United Kingdom and United States being the largest players.

Expressways make up only 1,208 kms of India’s road network. These high-speed roads are four-lane or six-lane and predominantly access controlled. The government has drawn up an ambitious target to lay another 30,000kms of National Highways in the next 5 years under National Highway Development Programme.Besides these, the government has bold targets of laying another 18,637kms of brand-new expressways by 2022.

India has primarily bitumen-based macadamised roads. However, a few of the national highways have concrete roads. In some locations, such as in Kanpur, British-built concrete roads are still in use. Concrete roads were less popular before 1990s because of low availability of cement. However, with large supplies of cement in the country and the virtues of concrete roads, they are once again gaining popularity. Concrete roads are durable, weather-proof, and require lower maintenance vs. bituminous roads. Moreover, new concrete pavement technology has developed (such as cool pavement, quiet pavement, and permeable pavement) which has rendered it more attractive and eco-friendly. With improvement in technology, concrete roads are marginally cheaper or equal to the cost of building bitumen roads. The maintenance of concrete roads is cheaper vs. bitumen-based roads.

Every 1km of two-lane concrete road has the potential of consuming minimum of one thousand tonnes of cement and hence for every 1,000kms of concrete road to be built, the potential cement consumption is ~1mn tonnes. With increase in the number of lanes, the cement consumption increases — the extrapolation is likely to be nearly 1.8 times.

Assuming all incremental highways are build out of concrete, the potential cement consumption can be phenomenal — more than 100mn tonnes, assuming four-lane highways, over the next 4-5 years or around 20mn tonnes every year.

Can this really happen?

The cement consumption in India as of now is expected to be ~265mn tonnes for FY15. The collective expectation of cement consumption growth is 8-10% p.a given the current optimism, which translates to an absolute volume growth of ~27mn tonnes p.a.

Interactions with people in the know suggest that it is impossible that the entire incremental road network will be concrete — this figure could be about 50% (at best). This means not more than 50mn tonnes (at best) of cement demand will come from road projects over the next 5 years (10mn tonnes every year pan-India). While this number seems to be substantial, when compared to housing (which should continue to grow by 8-10% p.a.) the road sector’s best-case incremental demand is still much lower. Housing will continue to generate and incremental demand of more than 15mn tonnes every year.

The collapse of cement demand over the past few years was largely driven by lack of infrastructure development and policy failures. Housing demand growth stayed positive and strong. While some leading cement manufacturers still believe that road projects can be a game changer, research does not fully validate this theory.

Can road projects be a game changer?

Though demand from road projects will definitely boost overall market sentiment, it is unlikely to be a material game changer. Supplies to such projects will be at steep discounts and unlikely to boost margins. However, supplies to these kinds of projects will definitely help cement manufacturers to stabilize their plant utilisations at better levels and gain on efficiencies, but it is highly unlikely that (barring the efficiency gains) the profitability of cement manufacturers will improve due to road project supplies. Many small-scale manufacturers are willing to compromise on prices to gain on volumes.

The Dirt of Concrete: The reality of road projects

Road projects involve huge amount of cash investments. Turning to concrete may be cheaper, but it is not very easy in a populous country like India with a large bureaucracy.Why? Let’s find out:

Incomprehensible but true: Less maintenance with concrete means = fewer repair contracts — not acceptable: Concrete roads need less repair work vs. bitumen-based roads. While the service life of concrete roads is around 40 years, the service life of bitumen-based roads is only around 10 years. Bitumen-based roads require a surface re-dressing every 3-5 years (at least once) while concrete roads generally don’t need any. Therefore, the value of repair contracts for concrete roads is less — this discourages stakeholders from building concrete roads unless it is a prestigious project that showcases the country’s road network. Road projects involve huge sums of money and hence huge bribes and commissions.Therefore, the preference is for contracts of a recurring nature – this optimises the financial status of stakeholders.

Black marketing of cement / other raw materials: Government contracts with cement manufacturers are mostly at subsidised rates. Contractors frequently divert the subsidised cement procured for road projects to other commercial projects such as housing for financial gains. Road projects lack governance on execution and become a hub for corruption and malpractices. If the government of the day is serious, then it will have to put strong mechanisms in place to weed out corruption.

Wrong belief that this is the best sort of regular employment: Most stakeholders wrongly believe that rebuilding roads at regular intervals helps generate employment for the poor. The truth is that these stakeholders do not want to let go of any opportunity of minting money for themselves.

What the transport minister’s ambition of building concrete roads translates into…

Recently the Union Minister of Road Transport and Highways made a number of strong remarks that marked his ambition to switch to concrete roads for new construction. However, the possibility of this switch depends on tie-ups with cement companies for cheaper rates. Media reported that the minister expects a rate of Rs160/bag for such contracts. Listed below are the responses of various stakeholders:

Government’s take: Authorities with leading PSUs responsible for development and maintenance of road networks across the country believe that the government does not have clarity yet about how much (percentage) of the new roads should constitute concrete. These authorities said that when the government invites the tenders for roads, it does not really specify the type – the selection (concrete vs. bitumen) is largely left to the discretion of the road contractors. The government of India does not have any set guidelines for concretisation of roads as of now. PSU authorities believe that the figure quoted by the media is the minister’s own and personal expectations (they said the minister believes he will be able to forge long-term contracts with cement manufacturers at Rs 160/bag).

What cement manufacturers say: Most large cement manufacturers (across the region) believe that it will be impossible for them to supply cement at Rs 160/bag. However, if the government is willing to waive off all cess/duties, the price is workable ex-works/factory. Smaller cement manufacturers in South India seemed excited about such contracts. It seems that smaller manufacturers are happy to compromise on their EBITDA levels if such contracts can assure them of higher utilisations. The logical conclusion is that such contracts would be a threat to the existing pricing discipline of the industry. Even if the supply of such contracts will be largely on a non-trade basis, trade prices are bound to get impacted.

What contractors say: Local contractors and people responsible for construction of roads seem very excited with the minister’s energetic statements about expediting construction of roads across the country. However, they are not confident about the execution transparency, assuming such contract terms are agreed upon. Some contractors believe that such cheap contracts will lead to large-scale black marketing of cement. Contractors believe that to ensure full transparency in procurement, delivery and execution, it would be wiser to keep the price at a more realistic level. Sources revealed that state governments in central India are likely to agree to enter into contracts with cement manufacturers at Rs200-210/bag for road construction.

To summarise, few cement manufacturers strongly believe that cement demand for concretisation of roads will be the game changer for the fundamentals of the industry. However, in reality, housing will remain the primary driving force for cement demand. It is possible that cement demand for construction of roads may lead to a spurt in despatches, but whether this will be favourable to the sustainability of better cement pricing continues to remain a question.

Creation of Telangana raises hopes for south demand: South India is a bottleneck for the fundamentals of cement sector, especially Andhra Pradesh (including Telangana). With capacity at nearly 80mn tonnes in AP, the issue of excess capacity is almost too huge to address. Utilisations continue to remain between 45% and 55% in AP. With the recent split of Telangana from Andhra Pradesh, a lot of expectations have built surrounding demand revival in south India — creation of new state capitals and support infrastructure in new states. Empirical evidence suggests that a split within the state results in material demand revival – Chhattisgarh from Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand from Bihar, Uttarakhand from Uttar Pradesh all caused a spurt in demand.

It remains to be seen if this will work for Telangana from Andhra Pradesh. Interactions with distributors, channel partners, end consumers, state authorities, corporate authorities (including the marketing and sales departments of various cement companies), housing builders, and contractors were not very encouraging for the near term. Most people believe that a lot has been said and talked about but when it comes to execution, things are still at a standstill. Politicians in ministries are still either settling down or negotiating for portfolios. Sources do not see a revival possibility for the next 6-9 months but remain very positive and confident of a significant demand revival in AP and Telangana over next 12-18 months. Housing demand in the current state capital of Hyderabad has come to a complete standstill after it was decided that the new state capital for Andhra Pradesh will be Vijayawada, which is now the preferred investment destination. However, Hyderabad could attract investments over the next 12-18 months.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access