Northeast India region (NER), India’s easternmost arm is connected to the sub-continent via a narrow sliver of a corridor squeezed between Bhutan and Bangladesh. Just like the narrow strip that connects NER with India, its relationship with the rest of the country over many decades has been tenuous at best. However, recent political commentary by the NDA government suggests that this region is likely to be in sharp focus during its tenure. Because of its inaccessibility and harsh hilly terrain, it has always retained an aura of mystery. To truly understand this largely unexplored, beautiful, and bountiful land, one has to actually spend some time there. Ground View toured NER extensively to uncover some of this region’s magic, especially from the standpoint of development potential, and especially of its relatively new cement industry. Interactions with bureaucrats, the local community, developers, contractors, and distributors revealed the region’s tremendous long-term growth potential, which is probably higher than the rest of India. Since infrastructure development will drive this progress, cement consumption in NER is likely to see strong growth. However, the dynamics of doing business in NER are not the same as the rest of India. Having had to face frequent natural calamities such as earthquakes, floods and landslides, man-made ones such as the numerous insurgencies and border conflicts, and a heavy perception of political apathy towards NER from the centre throughout India’s independent history, the people here tend to be wary of the motivations of what they perceive as outsiders. It is virtually impossible for an ‘outsider’ to set up a business here – many have tried, and even the mighty have fallen. Ground View takes you on an NER journey – not only through its picturesque cloud-clad mountains, not just to explore the potential of the cement industry, but also to the very heart and soul of the people who call this land of their own.

While India embarked on its difficult yet steady path towards progress and growth, NER remained largely ignored – its economy kept collapsing, it faced huge unemployment, and power supply was non-existent in many parts – even until as late as 2010 – this, in the region that holds India’s highest hydroelectric power potential and some of the highest literacy rates. Insurgent groups wreaked havoc, often extracting money from people and extracting ‘protection tax’ from local businesses. While some of these groups demand a separate state, others seek regional autonomy – some extreme groups even want complete independence. The relationship between these states and the central government, between the native tribal people and migrants from other parts of India, between its various factions – have been tense. It is widely believed in this region that successive political regimes in India have largely ignored NER due to the limited influence of its vote-bank – however, the centre has viewed it as challenging to govern due to the many separatist movements.

Newertheless, efforts have been on for a while now to create a more inclusive environment for NER withing India’s development framework. The North Eastern Council (NEC), constituted in 1971, is the acting agency for the development of the eight states. DoNER was set up in September 2001 with a view to expedite development in NER with governance and independence. PM Narendra Modi has remained steadfast in his commitment towards the development of NER – in his maiden budget, he allocated Rs 530bn toward NER while promising 14 railway lines, a sports university in Manipur, six agriculture colleges, Ishan Uday (scholarships for 10,000 students), and 18 FM stations.

Recently, Modi’s government made a deal with Bangladesh to develop a link between Tripura and Chittagong, thus increasing flow of products between NER and the rest of the country. In his Mann Ki Baat aired in July 2015 Modi had said “Is it possible to develop the northeast while sitting in Delhi? No. Officials will visit and see how it is to be done.”Many announcements have already been made by India’s transport minister, Nitin Gadkari, for developing roads in NER. Union Minister of Urban Development, Venkaiah Naidu, said recently at a conclave, “The people of northeast are the first to see the rising sun in India. There is no reason why we should not rise to the occasion to help the northeast reach its optimum potential.”

Minister Jitendra Singh from the Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region (DoNER) has invited women entrepreneurs from across the country to invest in NER and to take the lead in developing the region as an industrial hub. Mahesh Sharma (Minster for Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation) has said that the government was giving a big push to tourism in the country, with a special focus on tapping the huge potential of the NER. Assam’s Chief Minister Tarun Gogoi has urged DoNER to publish a white paper giving details of the funds it has released over the last 18 months for the development of NER. He also recently said, “Since DoNER has (now) come into being, NER should not be subjected to such shoddy treatment like the one meted out to the region by the present dispensation at the centre”.

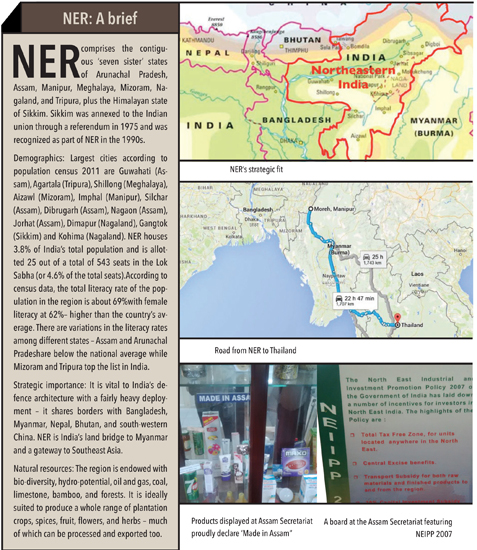

This is imperative, given the government’s increasing focus on this region. It definitely calls for a visit and a reality check. NER has seen many cement plants coming up since 2005; few are still in the pipeline. Even mainstream players such as Dalmia Bharat have shown interest in this region and entered NER through acquisitions, which were considered to be risky bets by peers and investors but yielding returns now. To evaluate opportunities and threats in NER, GV visited ministries, industries, infrastructure companies, contractors, cement distributors, factory sites, cities, and villages.

Most of the limestone reserves in NER are in Jaintia Hills district in Meghalaya; hence, almost all of the cement plants in the region are located here. Due to the difficult and hilly terrain where many places are inaccessible, the people have developed a tendency to resolve their problems without expecting outside intervention. In mining and related activities, external intervention is rarely seen and is not well tolerated.

For the cement industry, this means that all fuel-resource supplies are through the local community. In fact, it’s a common (and amusing) sight to find small piles of coal stacked at intervals besides the road across the hilly terrain. While there are many mining and crushing sites across NER, this region has virtually no external fuel supplies – hence the dependency risk on locals is huge. In certain cases, where limestone mining reserves are inadequate or not of cement-grade quality, few cement manufacturers choose to buy limestone from locals who own such limestone mines.

Though NER is lucrative, doing business here is not easy – the people tend to be mistrustful of ‘outsiders’. One has to belong to this region or else it becomes practically impossible to conduct any business, let alone succeed. Most successful business organizations in NER were started and are run by locals. This is visible in the case of the cement industry too. All cement plants have been set up by local business houses; outsiders have not been able to set up any greenfield projects so far. There are numerous examples of big business houses attempting to enter NER and not being able to succeed (such as UltraTech and Holcim Group). The ecology, topography, and the cultural ecosystem of the region makes it very different – it is virtually impossible for an ‘outsider’ to try to enter it. While Dalmia Bharat has established itself in this region (through acquisitions), it too faced enormous difficulties when it initially ventured into NER, for quite some time.

Mainstreaming NE states into India’s economy is a formidable challenge. These states have some unique economic problems arising out of remoteness and poor connectivity, hilly and often inhospitable terrain, poor infrastructure, sparse population density, shallow markets, inadequate administrative capacity, low skill endowment, and a law and order situation frequently threatened by insurgency.

People are conservative: Although emerging lifestyles (at least in urban / semi-urban areas) are veering towards the modern, most people here remain conservative. They do not appreciate outside interference, which they perceive as ‘invasive’. For an outside business to succeed here, it is very important to connect to the local people – this is perhaps the reason why Dalmia Bharat chose Mary Kom as its brand ambassador.

“NER is almost like a mini country in itself – its dynamics are very different from any other region in India.”

Language barriers persist, but it is manageable: Like other regions in India, language barrier exists. NER has several active dialects in use, but very few are known to the outside world. Almost 15 ‘main’ languages are spoken in NER – Assamese, Nepali, Manipuri or Meiteilon, Kokborok or Tripuri, Nagamese, Mizo, Khasi, Garo, Bodo, Karbi, Dimasa, Mishing and Apatani, Bishnupriya Manipuri, and Rabha. Among the seven states, Assamese and Manipuri languages have been included in the eight schedule of the Indian constitution. But, within these main languages, there are many dialects, which are yet unknown (some are endangered). Since a lot of people from Bihar, West Bengal, and Bangladesh have settled in this region, one can get by speaking Hindi and Bengali, especially in Assam. But for more insular and isolated states, such as Meghalaya where Khasi and Garo are the most spoken languages, this may not work. Bangladesh, where Bengali is the official language, is so close to some parts of Meghalaya that its mobile networks are visible in the manual selection mode of mobile handsets in this region.

God-fearing people: People here are god fearing – one possible reason for this is the frequent natural calamities that they have to deal with such as floods and earthquakes. These calamities also act as barriers to what they perceive to be the ‘outside’ world and ‘outsiders’, especially for the businesses that are eager to venture into this region

Sense of belonging is huge: Most of the people here are very attached to their lands, their villages, their towns – whatever part of NER they belong to. It is very rare to see people leaving their homes and states for higher income and better lifestyles – something that is becoming increasingly common across all parts of India. People here seem to be happier to remain close to the place that they were born in – this is not to say that they do not have aspirations – they do. However, their aspirations do not appear to be as high as in other regions in India. The people here appear more satisfied with their life and lifestyle – they seem self-contained and happy to grow within the region rather than without. Although people here do not have a closed mindset exactly, making them accept new ideas is quite challenging.

People seem unsure about their inclusion in India’s growth: People here have their own reservations about being a part of India and yet being left to their own devices for years, largely ignored by successive political regimes. They feel worried about their region’s inclusion in India’s growth. While politics is to blame, it is also because of the sheer physical isolation of NER, and also due to the conservative outlook of the people here and their attachment to their land –this remains a key bottleneck to growth. It is probably the reason why many ministers have increased their visits to NER, largely to reiterate the centre’s commitment to this region.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access