“We used to find it very hard to make our daughter drink milk. A friend of mine told me about a premium milk brand based on the concept of farm to home. We liked the idea and called up their customer care number. They started delivering the bottles in a couple of days. While I found it difficult to differentiate the quality, my daughter immediately took to its taste. My parents say this is the kind of milk they used to have during their childhood back in villages. My monthly milk bill is up more than 2x, but I feel it’s worth it,” says Padmanabhan Ramadas of Khoparkhairane, about the premium milk brand Pride of Cows. Premiumisation in liquid milk is a challenging concept, but recently, brands such as Pride of Cows or Sarda Farms are trying to carve out a niche for themselves (positioning) by catering to quality-conscious consumers. It now seems that an industry, which has punched significantly below its weight – has finally arrived.

Dairy business in developed markets is lucrative – some of the most valuable companies in the world (Nestle, Kraft, and Danone) have made their fortunes in this space. However, India’s dairy landscape has been markedly different from the developed world – no major company (except maybe Nestle) has made an impact here. This is quite surprising, considering that India is one the world’s largest producer and consumer of dairy products. Nevertheless, the Indian economy, marked by the trend of rising consumerism, holds immense potential for the dairy industry. For companies to realise the full potential of this lucrative industry, it is imperative for them to get the business mix right and to have the ability to invest in the long-term. Whichever way one looks at it, it seems like the dairy industry’s time has come.

In India, dairy is a very sensitive industry because of the sheer number of people involved. “The welfare of farmers and animals is the most critical aspect of the business,” says Mr R S Sodhi, MD of Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation, which markets its products under the iconic brand Amul. The number of people involved in the dairy industry in India is the largest in the world. However, the industry is still largely unorganised. Small farmers (who do not own more than two animals) produce nearly 80% of milk. Because of this, most farmers are unable to get advantages of mechanisation that large herds can avail of – hence, milk yields in India are very low. The World Society for the Protection of Animals pegs India’s average yield per dairy cow per year at 1.3tonnes vs. 6.2tonnes in the European Union and 9.1tonnes in the United States.

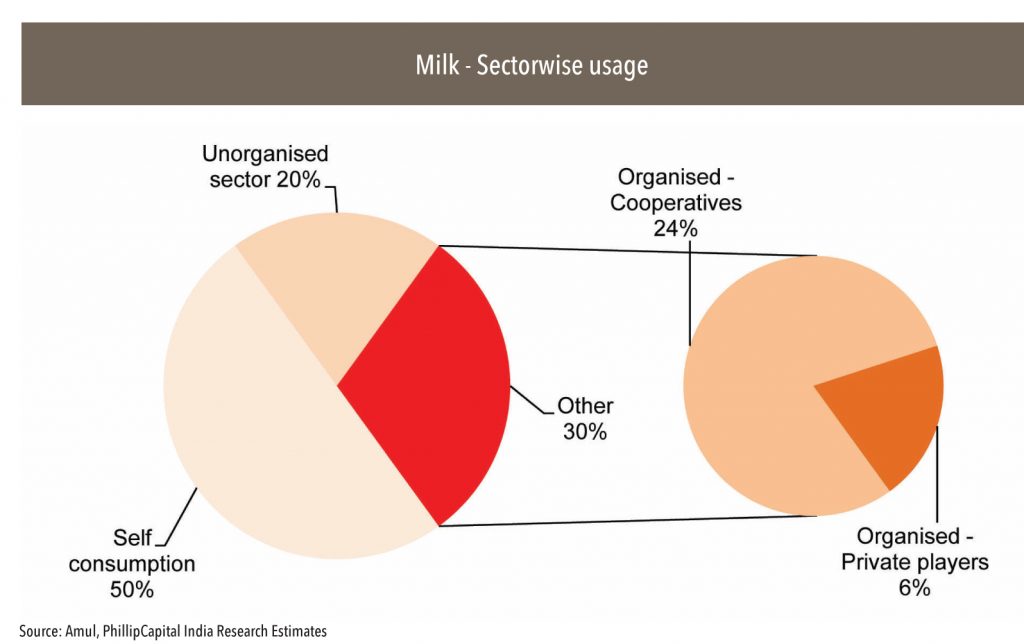

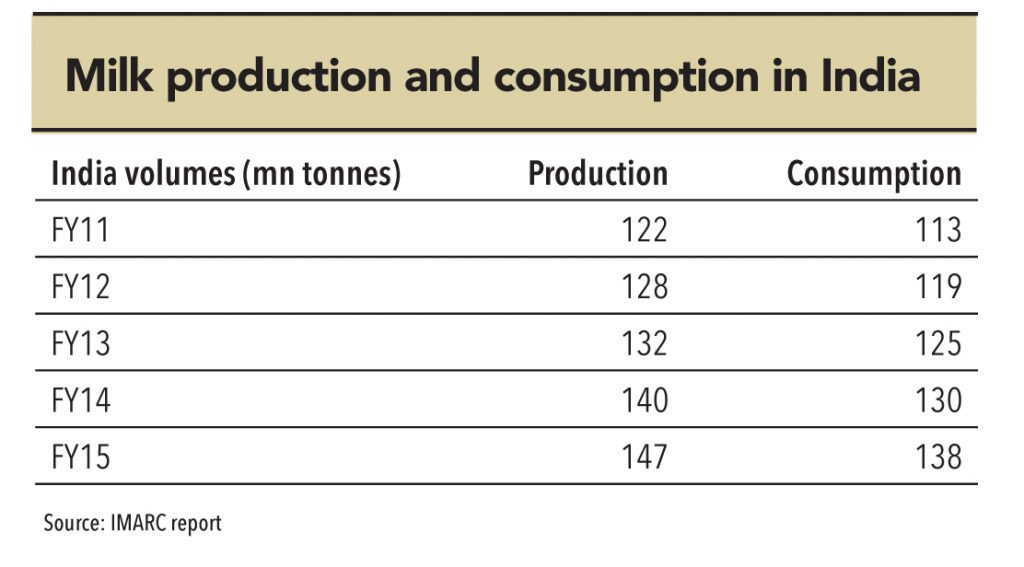

It is not just the milk sourcing, it is also the structure– the unorganised sector accounts for 70% of total volumes. Half of the 140mn tonnes of milk produced in FY14 was consumed at source. Out of the remaining 70mn tonnes, 28mn tonnes or 40% was sold to the organised sector and the rest to the unorganised sector. Co-operatives dominate the organised dairy industry (80% of revenue) because of raw-material sourcing dynamics working in their favour.

– Due to small average herd sizes, milk yields in India are far below global averages

– The unorganised sector accounts for 70% of India’s total dairy volumes

Sourcing is the key, therefore co-operatives have dominated India’s organised dairy industry so far

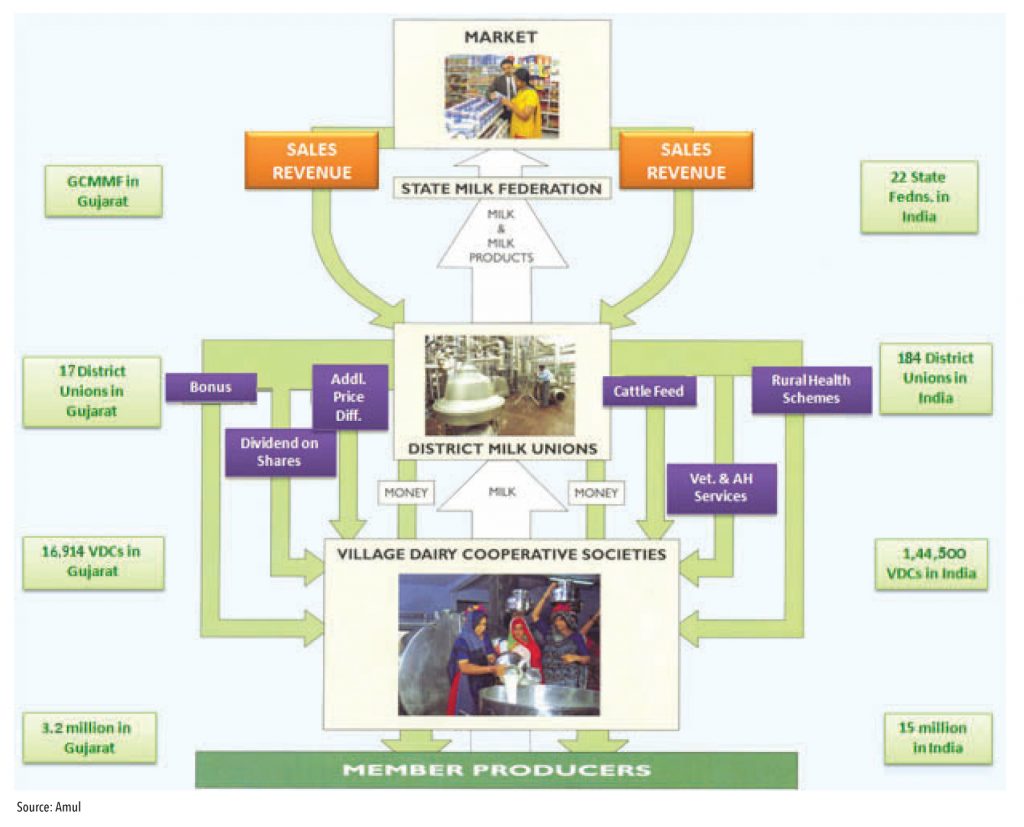

Because of the highly fragmented and unorganised nature of the industry in India, co-operatives have become the primary business model. Their success is based on two major facets of their business model:

1.Milk-farmer members own the shares of a co-operative, whose objective is sustainable input cost maximisation and co-operatives work on a no-profit no-loss principle, thus benefitting farmers. This is unlike private players, whose objective is to increase profits sustainably.

2.Co-operatives’ mandate is to procure all the milk that farmers can supply at a set price, regardless of the demand.This provides small farmers with security.

The co-operative model has enabled small milk farmers to command a lion’s share of profits from their produce and to reduce their financial insecurity – a report by the World Society for the Protection of Animals says that small-scale (often landless) milk farmers in India get to retain 77% of the total price paid by consumers. In comparison, producers in Germany retain only 48% and farmers in the United States only 45%.

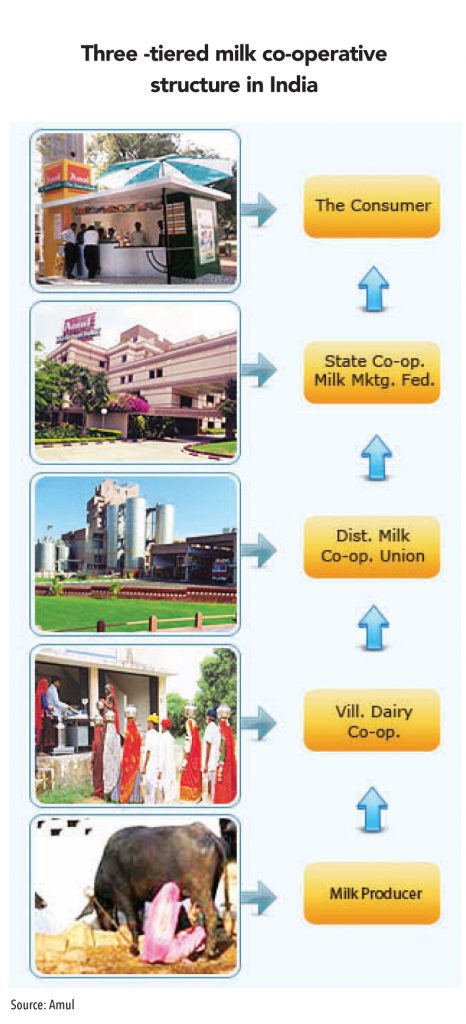

In India, most state cooperatives follow a three-tiered structure,

also known as the Amul model:

• Village-level ‘Dairy Co-operative Societies’ (DCS) – collect surplus milk from farmer members

• District-level ‘Milk Unions’ – collect milk from all DCS’ in the district, process, and market it

• State-level ‘Federation’ – provides marketing services and other support to District Milk Unions

Indian milk producers (majority of whom are farmers) retain a large share (77%) of the price that consumers pay for the milk

In Gujarat and Karnataka, state co-operatives direct all district co-operatives to market products under a single umbrella brand (Amul for Gujarat and Nandini for Karnataka). In other states, such as Maharashtra, the co-operative structure is weak and each district milk union markets goods under a different brand (Katraj in Pune, Gokul in Kolhapur).

The Managing Director of a district cooperative in Maharashtra (who did not wish to be named) says, “States that have a common state-wide dairy brand have outperformed weaker ones that don’t have one. This is because of consistency and economies of scale in marketing products, which helps strong states strengthen their sales and distribution chain.” He explains what is wrong with the state-controlled side of Maharashtra’s dairy industry – “In Maharashtra, the state co-operative markets products under the Mahananda brand, which is distinct from district-level brands like Katraj, Gokul and others. To complicate things further, the government of Maharashtra also markets dairy products under a distinct Aarey brand. In Maharashtra, as district milk unions, state cooperatives, and the state government compete amongst themselves for market share, individual brands lose their economies of scale, impacting sales potential for cooperatives– thereby paving the way for private dairies.”

Besides sourcing skills, the presence of a strong single state-wide brand seems to be the cornerstone of a co-operative’s success

Pune co-operative brand – Katraj

Ahmednagar co-operative brand – Rajhans

Maharashtra state co-operative brand – Mahanand

Kolhapur co-operative brand – Gokul

Maharashtra government brand –Aarey

In Maharashtra various brands of district and state co-operatives, and government compete among themselves for market share. In contrast, in Gujarat all district and state co-operatives market milk under common brand Amul

While Gujarat co-operative’s Amul brand has been a success story and competes with not only strong domestic brands, but also with global ones, Maharashtra’s local co-operative brands (Mahananda and others) have been ineffective in competing with other co-operatives and private brands. This has adversely affected the bargaining power of milk farmers. “In Maharashtra, where procurement prices for milk have reduced to as low as Rs 15-16 from Rs 25-27, the situation is particularly exacerbated because of lack of a strong cooperative. In Gujarat, the situation is much better because our procurement prices are significantly higher”, says Mr R S Sodhi of Amul.

Milk co-operatives not only offer farmers among the highest prices for milk procurement, but also have a mandate to purchase all the milk that a farmer sells, irrespective of near-term demand. Private dairies and bulk-milk traders, which generally procure milk at lower/equal prices, also play an important role in milk production. Prabhat Dairy sources 65% of its milk directly through farmers and buys the rest from bulk-milk vendors. Kwality Dairy procures as much as 85% of its milk from vendors.

Why should private milk collectors exist?

Even as co-operatives offer the highest procurement prices to farmers and buy all the milk for sale, private dairies and bulk-milk vendors tend to be stronger in villages with lower access to organised banking. In these villages, small farmers borrow funds from local landlords, and in many cases from private milk collectors. These small farmer-borrowers, in many cases, repay milk collectors in kind – by supplying milk. As farmers develop an association with private milk collectors, and once the latter become a reliable source of funds, farmers begin selling milk regularly to these private milk collectors, despite co-operatives offering higher prices.

Room for all, even in the long term

The business models of private players and co-operatives are in perpetual conflict, but India is and will continue to be a surplus producer of milk with a very large unorganised market (even in the very long-term), and this provides room for all types of players. However, co-operatives have been aggressively competing for market share, keeping selling prices low – this has impacted the quality of products and profitability of the industry.

Co-operatives’ practice of keeping selling prices low and maximising buying prices has affected the quality of products

Subsidies offered to co-operatives embolden the strong ones

For nearly three years (from July 2013 to January 2016) the Karnataka government provided a subsidy of Rs 4 per litre to dairy producers and families. In January 2016, the government increased this subsidy to Rs 7 per litre. As a result, farmers in Karnataka get ~Rs 28 per litre for cow milk (including Rs 7 in subsidy). In such states, private dairy players’ profitability and business model comes under threat due to such high procurement prices. Hatsun Agro, a key private player in the south, procures milk directly from farmers in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh – but it does not have direct sourcing capability in Karnataka.

Some co-operatives become stronger because of government aid and manage to expand their presence in states or districts with weaker co-operatives.The weaker cooperatives find it challenging to survive when strong cooperatives such as GCMMF or Nandini come to challenge them in their turf. To maintain profitability, the milk procurement prices in weak states drop and private players begin to co-exist with co-operatives (procurement prices drop as no major co-operative is in a strong-enough position to set prices for the market to follow). In Maharashtra, milk procurement prices are significantly lower than those in Karnataka. As a result, private players in Maharashtra like Parag Milk Foods and Prabhat Dairy have been able to set up a local sourcing chain from farmers.

In developed markets, reconstituted milk is sold at a significant discount to fresh milk. This form of adulteration is one of the minor ones. Adulteration of milk happens throughout the supply chain in India and it is one of the biggest problems of the dairy industry. This means that there is a huge opportunity for the supply of high-quality milk. However, the economics of the business are rather complex and profitability is a challenge. Recently, private players such as Parag established brands based on the ‘farm-to-home” concept by following global benchmarks of quality and freshness. Growth was superlative, but profitability and scale remain a challenge because of the huge fixed-cost structure of the industry. Even so, it seems that the Indian dairy industry – with a vast array of products being introduced and private players willing to commit significant capital – has truly arrived.

DID YOU KNOW? Some of the milk that you consume or buy as ‘fresh milk’ is actually reconstituted milk!

“What is pure in today’s market? Every other product is adulterated. Likewise, milk and milk products are also adulterated. It is a knife fight in the market.Nobody can compete fair,” reveals the MD of a leading milk co-operative in Maharashtra. Milk is a seasonal product with rising production during winters while production declines in the summer. Excess production of the winter season is stored in the form of milk powder, which is a global commodity.In cities such as Mumbai, where there is a significant gap between demand and supply, the share of reconstituted milk (milk made from milk powder) is very high. Milk vendors do not label milk as reconstituted, and pretty much everything is sold as fresh milk.

The Managing Director of a leading co-operative in Maharashtra tries to explain the competitive relationship between Maharashtra’s co-operative and government milk company with a hilarious cow and bull analogy – “The conflict between the two bulls for the cow has raged on for decades, making them so tired that a third bull was able to exploit the opportunity,” he chortles. In Maharashtra,the government milk company is Aarey while the state also has quite a few cooperative brands. The battle for market share resulted in the weakening of both Aarey and co-operatives,which in turn led to private companies winning market share. In Maharashtra, milk procurement prices are now one of the lowest in the country, as no major co-operative has been able to set prices for the market to follow. This has not only helped private players establish their business models, but cooperatives from other states have also forayed into the market.

Indian dairy negatives -> lower profitability than global average -> lower investment -> lower productivity and lower quality products

This phenomenon is seen across many states – private players have been able to establish their brands, but the profitability of the industry is significantly lower than in developed markets. Lower profitability meant that investments have been below par while in reality this industry requires huge investments in supply chain, factories and farms. Due to this, the number of dairy brands known for their quality is very few.

Indian dairy positives -> growing per capita consumption, growing scope for value-added products and premiumisation

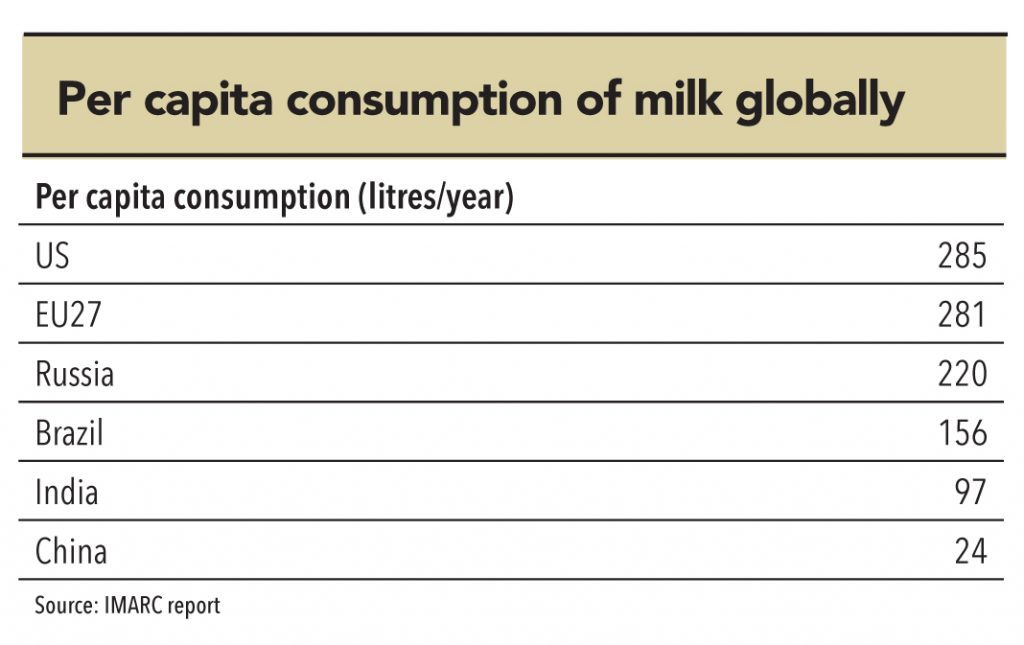

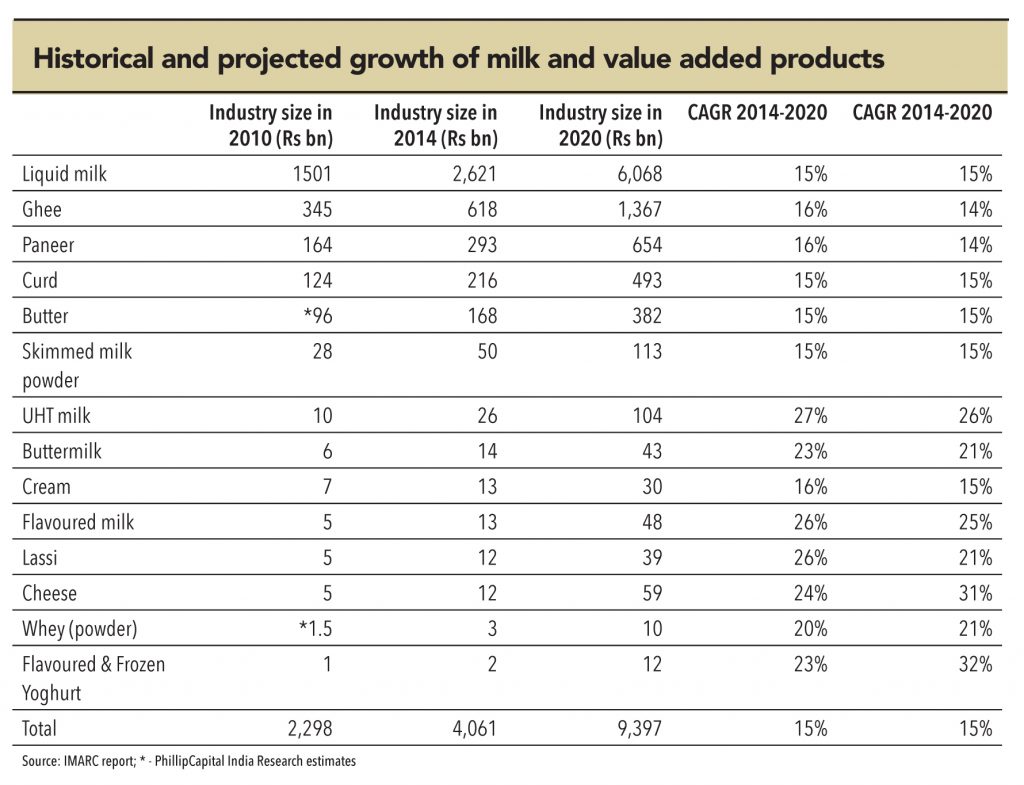

Although profitability is low for the industry, growth is not a concern. The per-capita consumption of milk is growing, but more importantly, value-added products are growing faster. This segment has higher gross margins and immense scope for premiumisation. However, there is a catch – value-added products and liquid milk supply chain economics are inextricably linked to each other.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access