D-Mart’s explosive market debut could be the start of something…

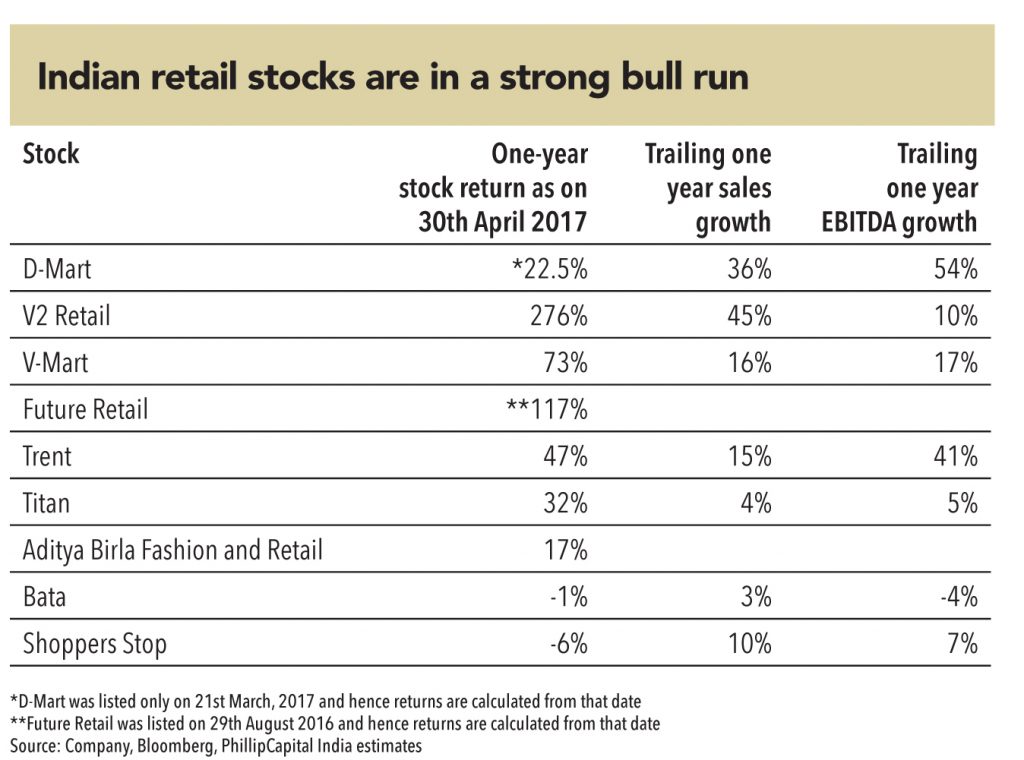

Dalal Street recently saw the listing of one of the most successful IPOs in recent times – D-Mart. The company is a play on the fast-growing modern retail space in India. D-Mart’s stock listed at Rs 604, netting gains of more than 100% on an issue price of Rs 299. Investor confidence in D-Mart seems well founded if one considers its strong growth trajectory and the perceived superiority of its business model vs. unsuccessful retail models in India. However, it is not just D-Mart, but the entire retail pack that has captivated the investor community recently. In the last year, most retail stocks have generated returns of more than 15%, with some far higher, hinting at either excessive exuberance or an inflexion point in the growth trajectory for organised retail in India.

…but the last retail bull-run did not end on a happy note

This is not the first time that Indian retail counters are exploding on the ticker. In 2005-08, many retail stocks (such as Pantaloons Retail and Vishal Retail) gave returns in excess of 100% within a few months. However, back then, it did not end well for most retail companies – by 2009, most stores of Vishal Retail were closed down due to misallocation of capital by its management; it was eventually sold to investors in 2011. Similarly, reeling under skyrocketing debt, Future Group was forced to sell its Pantaloons chain to the Aditya Birla Group in 2012. Another prominent retail company, Subhiksha, which had deferred its IPO indefinitely in December 2007 in anticipation of better market conditions, was forced to close all its stores in 2009 due to capital mismanagement.

What makes a retail model successful and what leads to its possible doom? In this Ground View, we attempt an in-depth analysis of different business models that exist in the Indian modern retail space and try to determine, through global examples, ground research, and existing literature, which business models are best poised to succeed in India.

The Indian retail industry is one of the world’s largest at US$ 616bn and is likely to achieve 12% CAGR to touch US$ 960bn by 2020, as per Technopak. It has multiple levers of long-term growth such as favourable demographics, low penetration of various consumption categories, and rising aspirations due to economic growth and urbanisation.

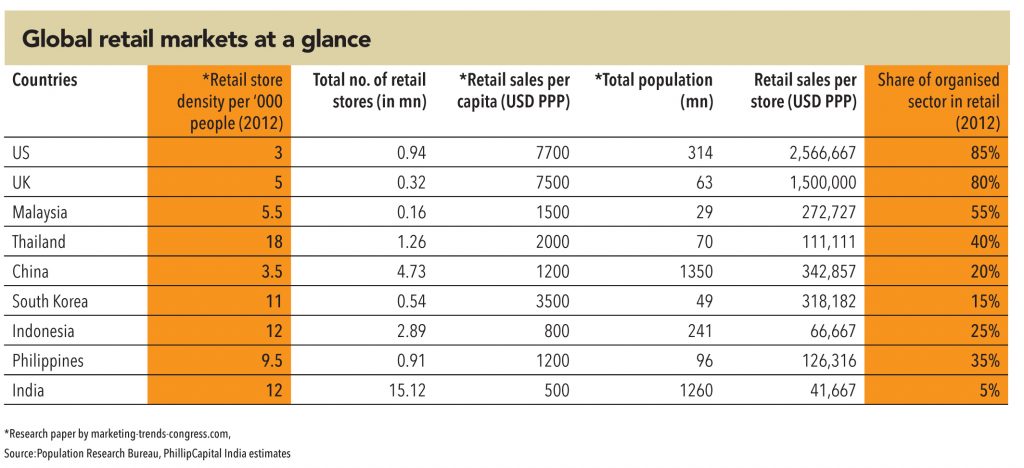

While the Indian retail industry may be as big as the retail industries in the world’s leading economies, the Indian landscape is very different from most of its emerging and developed-market peers. As per AC Neilsen, the Indian market is highly fragmented with 15mn retail outlets (mostly small mom-and-pop stores) operating across the country. This translates to 11 outlets per 1,000 people – one of the highest retail densities in the world.

With 15mn retail outlets, India has one of the highest retail densities (11 outlets per 1000 people) in the world

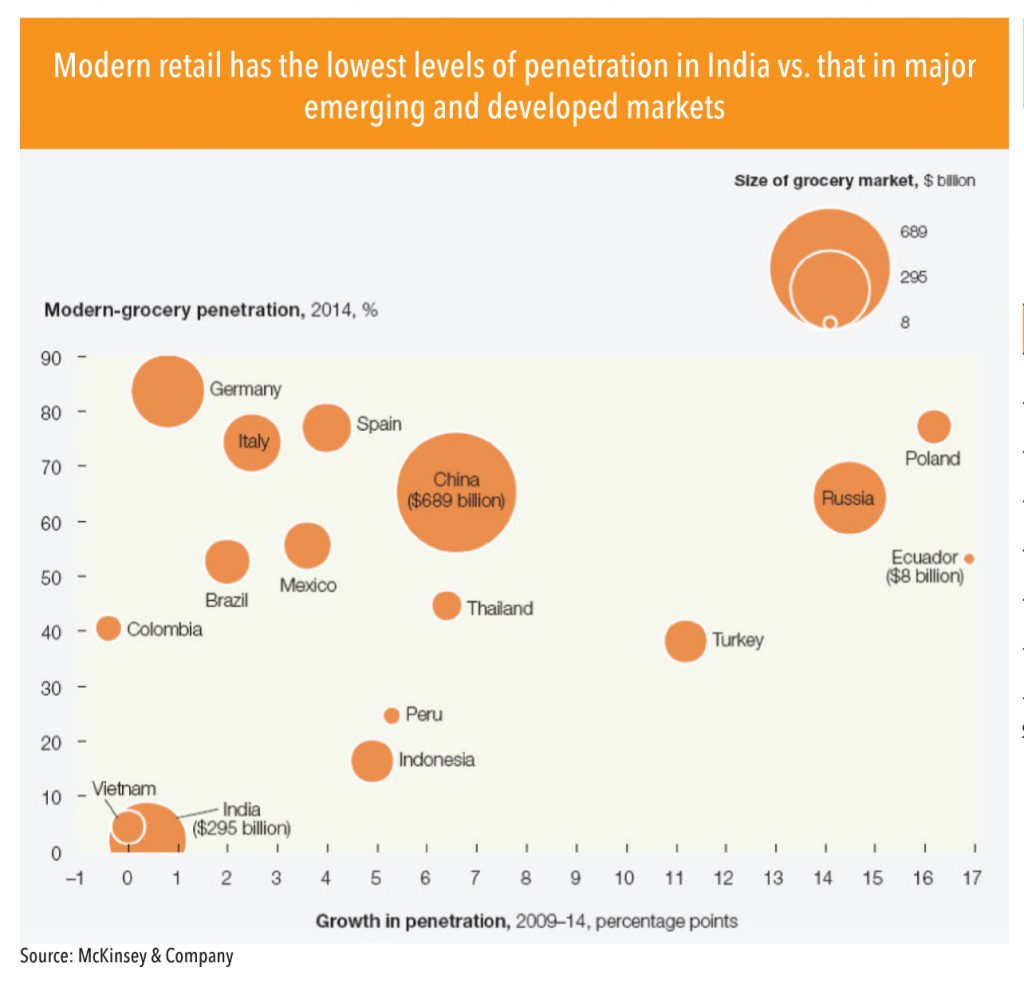

In India, organised retail accounts for less than 10% of total retail sales, as per Technopak – demonstrating the dominance of smaller retail outlets. In contrast, the share of modern retail in emerging markets such as China, Indonesia, and There are many factors that contribute to the continued control of small retail outlets on India’s retail landscape.

The average Indian consumer prefers smaller SKUs: Unlike consumers in other major retail markets, which prefer purchase of larger SKUs due to significant cost savings, the average Indian consumer tends to prefer smaller SKUs due to the lower cash outlay involved. An example – HUL brand Clinic Plus’ one-rupee shampoo sachet has been its largest selling SKU in its hair care portfolio for a very long time. Small SKUs dominate sales of many FMCG and grocery categories, and account for a sizeable share of revenue for most FMCG companies. As modern trade Philippines is far higher at 20%, 25%, and 35%.

Under-penetration of organised retail is more striking in the foods and grocery segment (modern retail) which dominates retail spending in India (c. 67%). Just 3% of sales in foods and grocery categories are through organised retail (as per Technopak), putting India at the very bottom in modern retail penetration globally. normally offers discounts only on larger SKUs, and offers no benefit to buyers of small SKUs, most customers prefer to buy from local outlets due to convenience, availability of credit, and a personal relationship.

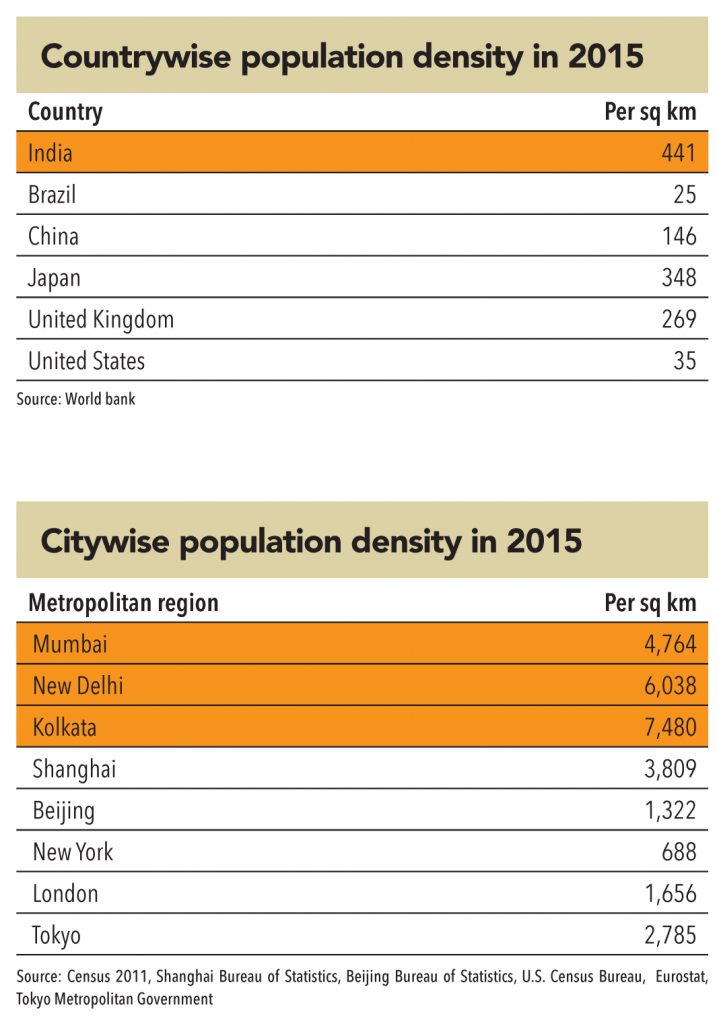

Higher population density: India’s population density, at 441/sq. km, is significantly higher than what it is in emerging and developed peers. The population density is even higher in Indian metros and tier-1 cities vs. other global cities. This kind of density, combined with consumer preference for local retail outlets, makes multiple retail outlets in the same locality, selling the same category of goods, financially viable.

Government regulations have hindered the entry of global retail giants while local modern retail is still in a learning phase: India was closed to global retailers for a long time. It only opened itself in 2012 when the government allowed 51% FDI in multi-brand retail. As a result, many global retail chains such as Walmart, Target, Aldi, and Seven Eleven, present in most major economies, are absent from the Indian retail landscape – though some have recently tied up with Indian companies for B2B retail. Also, Indian organised retail players are still in a learning phase – with many players still struggling to find a profitable and sustainable business model. As a result, competition for unorganised retailers in India is very limited vs. that in other countries.

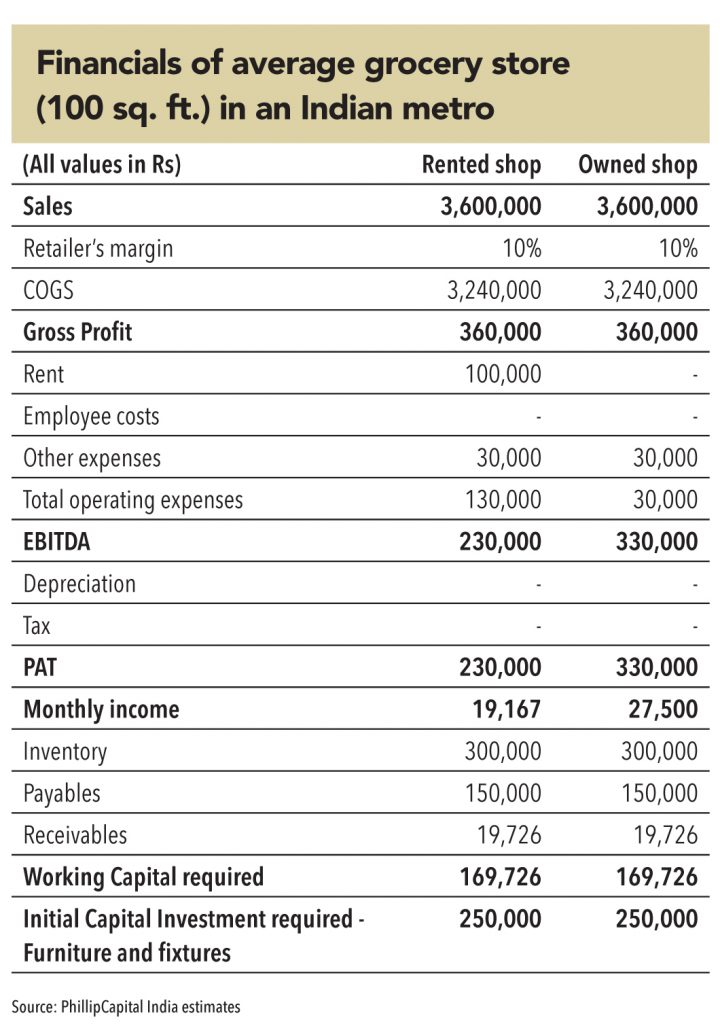

Lack of well-paying jobs and comparatively lower wages make retailing attractive: The per capita income in India (around US$ 7,200 in PPP) is far lower than that in emerging and developed peers, and below the global average of US$ 15,500, as per IMF. While an unskilled Indian labourer earns just Rs 5,000-10,000 per month, even a semi-skilled Indian worker makes only Rs 10,000-20,000 per month in most Indian cities. In contrast, a retailer with a 100 sq. ft. shop on rent can make around Rs 20,000 per month, with an initial investment of Rs 250,000 and working capital of Rs 170,000. Due to lower wages and lower employment opportunities for well paying jobs, many people in the workforce in India prefer retailing, which provides stable income, independence, and self-satisfaction. Retailing becomes even more attractive and profitable in a country like India with very high property ownership rates (866 per 1,000 households as per 2011 census) as it eliminates rental expenses. This can increase monthly earnings by up to Rs 8,000 – 10,000.

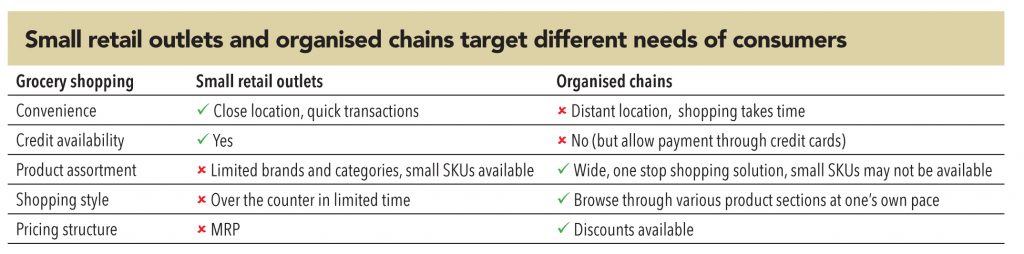

Mom-and-pop stores dominate the industry as they offer convenience of location, credit and quick transactions

While organised retail contributes to less than 10% of the total retail sales in India, it is growing faster than the overall retail industry. Mom-and-pop outlets tend to dominate the Indian retail industry as they offer convenience of location, credit, and a quick shopping experience. However, organised retail outlets have their own set of strengths, which make them a very attractive shopping destination for value-conscious and brand-savvy customers. These outlets offer an expansive product assortment, higher variety of brands, a one-stop shopping destination for various needs, and the luxury of shopping at leisure while browsing through sections of various product categories.

Within organised retail in India, modern retail (focused on the foods and grocery category) has the lowest penetration (3%) and is widely estimated to achieve 25% CAGR to touch US$ 31bn in 2020 from US$ 13bn currently as per Technopak.

What differentiates organised chains from unorganised retailers is the significantly high rate of discounting offered by the former due to their economies of scale

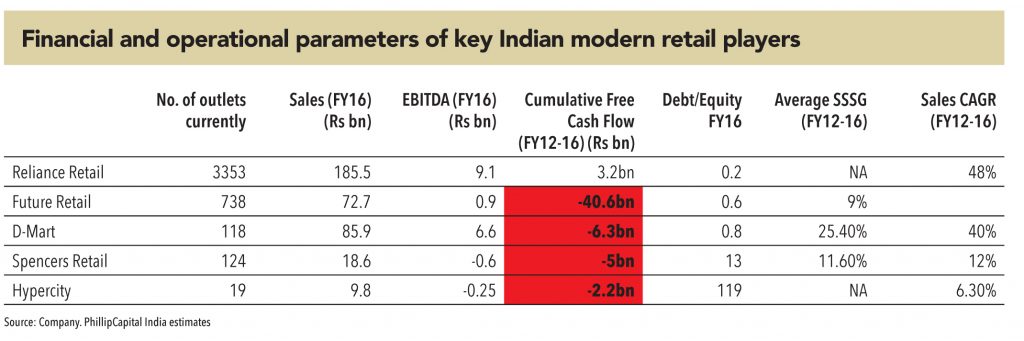

Modern retail in India is a fast-growing industry with most players reporting significant revenue growth. However, this has not translated into substantial profits. Most current Indian modern retail players suffer from structurally low margins, very high debt levels, and consistently negative free cash flows. The Indian modern retail industry is still in the learning phase and its search for sustainability is still ongoing. As a result, no modern retail company in India has the substantial size and scale that can be seen in the developed world.

Most Indian modern retail players suffer from structurally low margins, very high debt levels, and consistently negative free cash flows

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access