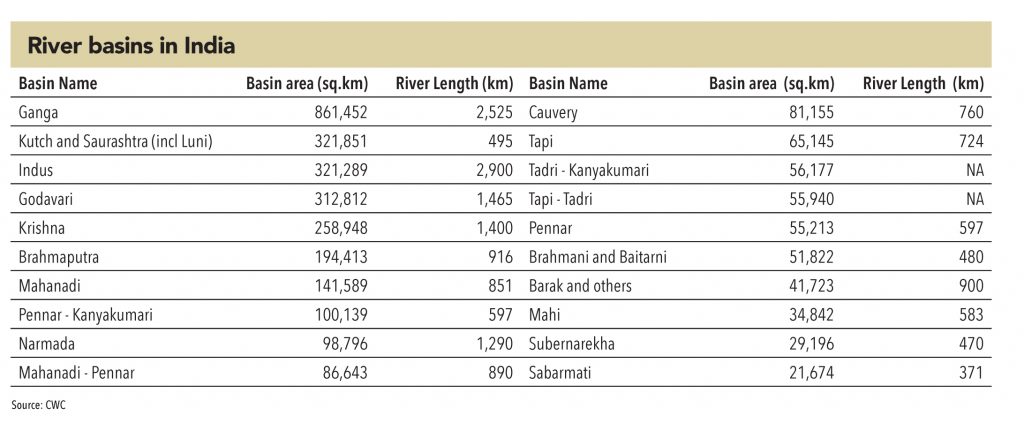

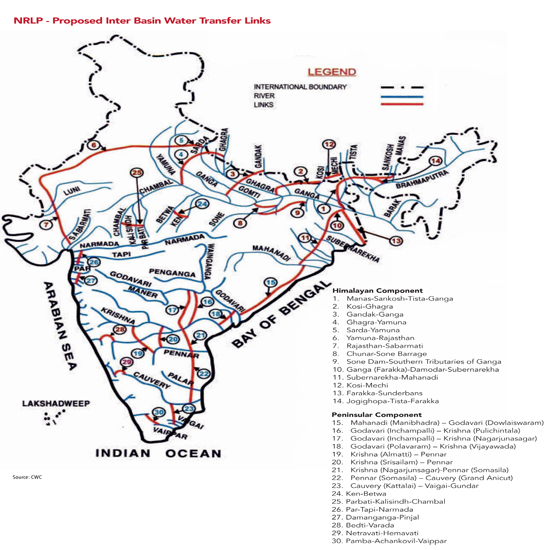

The Indian peninsula is blessed with as many as 111 rivers – the primary ones are Indus, Brahmputra, Ganga and Yamuna (in the Himalayan region) and Narmada, Tapi, Godavari, Krishna, Mahanadi and Cauvery (in the Peninsular region). The CWC has divided the entire country into 22 river basins – the largest of them is the Ganga river basin, with a catchment area of over 860,000 sq.km.

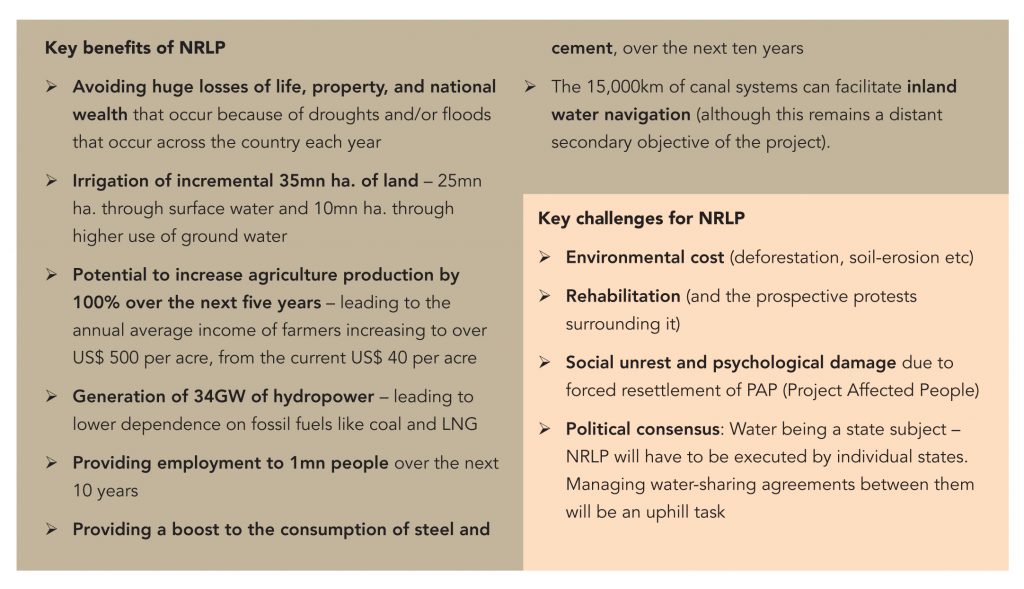

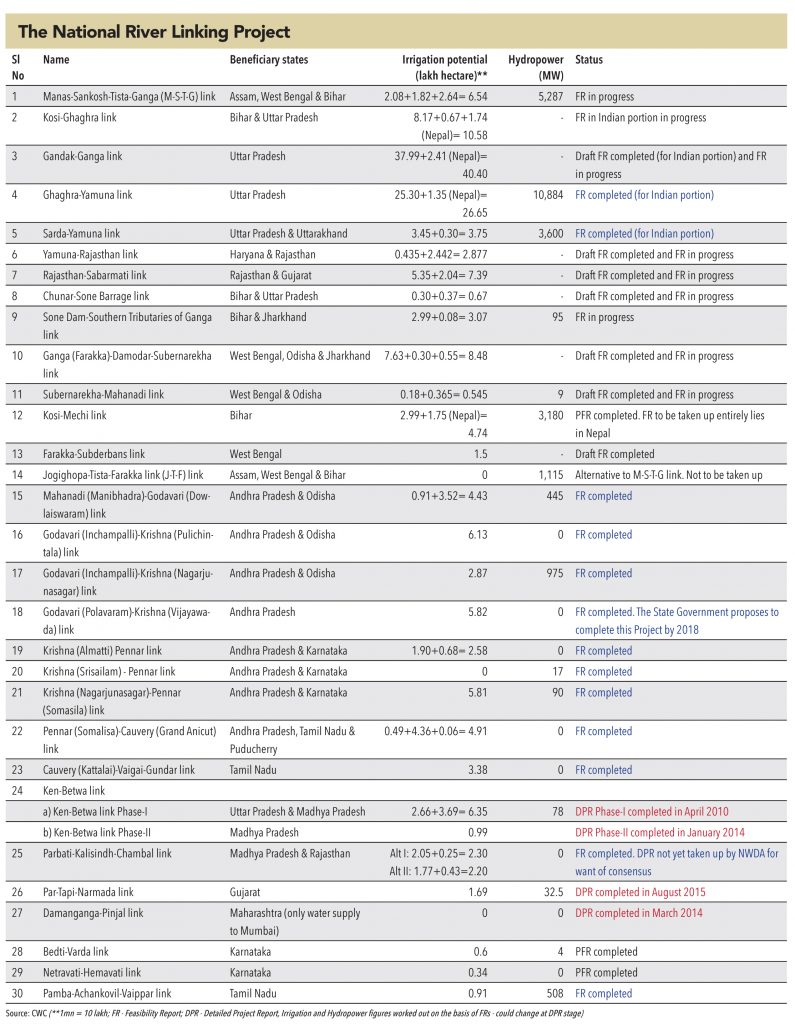

The National River Linking Project (NRLP) , in its current state, envisions connecting 37 rivers through 30 links comprising of a network of over 50 dams and more than 15,000km of canals – to form a gigantic South Asian Water grid. The canals, are planned to be 50-100m wide and more than 6m deep. The project is expected to cost Rs 5.6trillion (in 2002 prices) – or approximately Rs 11.5trillion (in 2015 prices). The NRLP comprises of two components:

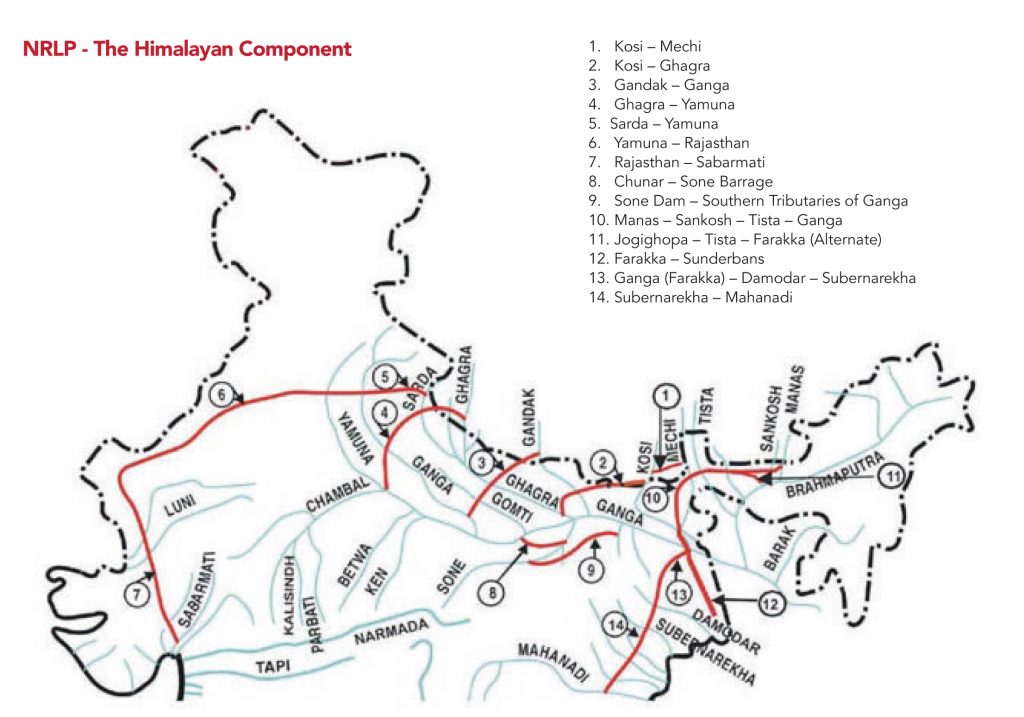

The Himalayan component of the NRLP consists of 14 links that propose to inter-connect and transfer surplus water from the Brahmaputra and the Ganga basin to the peninsular rivers. The idea is to ensure that the surplus water available in the Himalayan rivers in the monsoons is channelized to deficit regions (currently, this excess water results in drowning villages close to the banks). Most Himalayan rivers are perennial, so the Himalayan component will provide a lion’s share of hydropower capacity (24 GW of the total 34GW expected) from the interlinking project.

Key links in the Himalayan component are:

1) Manas-Sankosh-Tista-Ganga: This is, by far, the most ambitious and difficult to execute link. It seeks to connect the three tributaries of the Brahmaputra (Manas, Sankosh, and Tista) to the Ganga. It will be built across three states – Assam, Bihar, and WB – irrigating 0.65mn ha. and generating 5.3GW of hydro power. The execution of this project will be a challenge, considering the terrain. The project might also face hurdles in the form of opposition from China (Brahmaputra runs as river Tsangpo in China) and Bhutan (though Bhutan shouldn’t be much of a problem as per GV’s interaction with a Central Water Commission member).

2) Kosi-Mechi and Kosi-Ghagra: Two links on either side of the river Kosi will seek to distribute its surplus flow to the rivers Mechi and Ghaghra, helping to irrigate areas in Bihar (1.2mn ha.), WB (0.175mn ha.), and UP (67,000 ha.). It is interesting to note that the river Kosi has changed its course significantly over the last few decades, and these links, which are still in consensus-building stage, might see significant modifications after reaching the DPR stage.

3) Gandak-Ganga: This is expected to be the most beneficial link in the entire NRLP – it will add an incremental irrigation area of 3.8mn ha. in Uttar Pradesh. It seeks to connect the lower tributary of the Ganga (Gandak, at the Indo-Nepal border) to the upper basin of the main river itself in UP. Nepal is also likely to add 0.2mn ha. to its irrigated area because of this project.

4) Ghagra-Yamuna: This link will connect Ganga’s tributary Ghagra to the Yamuna – all in Uttar Pradesh. This should be the easiest to execute, given that it doesn’t require consensus with any other state government. This project has the potential to add 11GW of hydropower capacity.

5) Yamuna-Rajasthan and Rajasthan-Sabarmati: These two contiguous links challenge the carvings of nature and seek to connect the Yamuna to the Sabarmati through Rajasthan. In terms of magnitude and nature of catchment area, these links should have a significant impact – they seek to take water to the desert state of Rajasthan, which suffers droughts every year.

6) Ganga-Subernarekha and Subernarekha-Mahanadi links: This is where the heart of this entire project lies – connecting the rivers in the northern part of the country to the southern part – the Himalayan basin to the Peninsular basin. The two contiguous links will connect the river Ganga to Mahanadi. Mahanadi, in-turn, is envisaged to be connected (many intra-state links already present) to the major rivers of the Indian peninsula – Krishna, Godavari and Cauvery – through the peninsular component. The direct benefit of this project is lower than other links (only 0.9mn ha. irrigation and negligible hydropower generation) but the indirect benefits of the surplus of northern rivers, to be diverted to the entire southern region, are immense.

7) Farakka-Sunderbans: This link, completely in West Bengal, is being built solely to channel excess water in the rivers Ganga and the Brahmaputra into the Sunderbans delta – mainly to avoid floods in the catchment areas.

8) Other links: Other links like Chunar-Sone, Sone-Ganga, and Sarda-Yamuna are smaller links in themselves, generating limited irrigable area and hydropower capacity. However, in the overall scheme of the project, they contribute significantly in managing excess water-flow in the Himalayan basin.

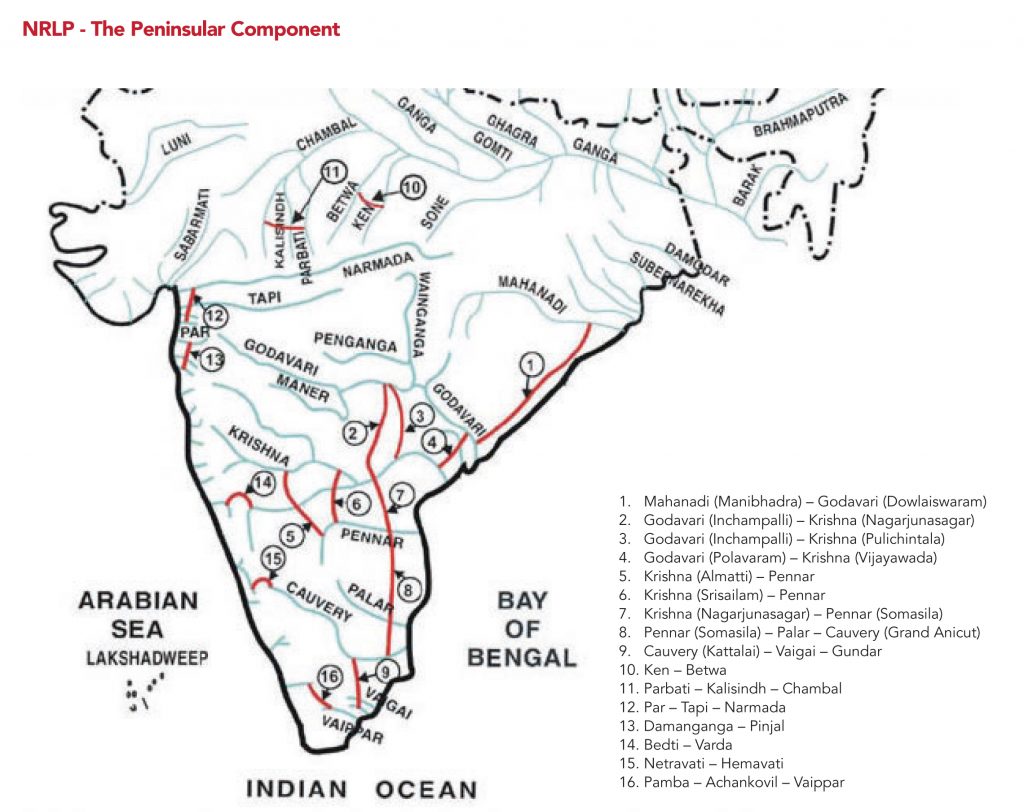

The Peninsular component of the NRLP consists of 16 links that envisage inter-connecting and managing the water flow of the peninsular rivers. This focuses more on the east-flowing rivers (Krishna, Godavari, Mahanadi, and Cauvery) rather than the west-flowing rivers (Narmada and Tapi). Under this component, only two links are proposed on west-flowing rivers and two are on rivers in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. The rest of the 12 links are for east-flowing rivers, benefitting Orissa, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala. It is important to note that these states see the highest volatility in terms of water-related disasters – they are hit by floods during the monsoons and by droughts in the dry months.

Given the fragmented political landscape of this region, consensus-building will be a tough exercise. We have already seen how the state government of Tamil Nadu has been defying the Supreme Court order on the Cauvery water-sharing arrangement. Getting these states on-board to accept mega projects like the river-link project – which propose long-term benefits but short-term pain (rehabilitation etc.) – could prove onerous.

Key links in the Peninsular component are:

1) Mahanadi-Godavari: This link will connect the two northernmost rivers of the southern half of the country. It will provide significant relief to regions in Odisha and Andhra Pradesh (affected by floods every year) by diverting excess water-flow towards the south and west. Significant irrigation benefits (0.44mn ha. of area) are expected through this link.

2) Three links between Krishna and Godavari: As many as three links are envisaged between Krishna and Godavari rivers, through Odisha and Andhra Pradesh. This is despite the presence of the mega dam (Nagarjunasagar) present on the Krishna river. These links will provide huge relief to areas of Andhra Pradesh that are perennially impacted by floods. A mammoth 1.5mn ha. of incremental area could be irrigated through these links.

3) Three links between Krishna and Pennar: Three links are also envisaged between Krishna and Pennar rivers. These links will pass through Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka and provide relief to areas of AP that are perennially hit by floods.

4) Pennar-Cauvery: This link is the final one, connecting all four large east-flowing rivers of southern India – Mahanadi-Krishna-Godavari-Cauvery. In fact, this link is envisaged to be built as a continuation of links 17 (Godavari-Krishna) and 21 (Krishna-Pennar). It will impact AP, Tamil Nadu, and Puducherry.

5) Ken-Betwa: This link envisages to provide relief from drought to parched areas of MP by linking the two Yamuna tributaries – Ken and Betwa. The project is in most advanced stages (DPR prepared and approved, environmental clearances obtained), and with favourable governments in both states (NDA), it could soon start execution.

6) Parbati-Chambal: This link, just like Ken-Betwa, is expected to provide relief to drought-affected areas in MP and Rajasthan. Just like Ken-Betwa, it should also see some action soon, with favourable government in both states (NDA).

7) Par-Tapi-Narmada and Damanganga-Pinjal: These links attempt to connect five west-flowing rivers in Gujarat and Maharashtra. The main objective is to prevent excess water from flowing into the Arabian Sea and harness it to provide relief to drought-affected areas in Gujarat, and also to the city of Mumbai. The projects are in advanced stages, with DPR already prepared and approved, and environmental clearances obtained. With a favourable government in both states now (NDA), the project is likely to start execution soon.

8) Other links: There will be three small links between small tributaries of east and west flowing rivers in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. The projects are in very early stages, and it could be a while before they see action (also because of the volatile political environment in the concerned states).

3.The water of the Colorado River (an international river between USA and Mexico) is supplied outside the basin to the Imperial Valley in California, which receives 3.1 MAF of water annually (as part of multi-state agreements executed in 1920-30s). About 180,000 people in the Imperial Valley receive approximately 70% of California’s allocation of water from the Colorado River.

Mahaweli-Ganga Development Programme in Sri Lanka: This is the largest integrated rural development multi-purpose programme ever undertaken in Sri Lanka and was based on water resources of Mahaweli and six allied river basins.

The main objectives were to increase agricultural production, hydropower generation, employment opportunities, and settlement of landless poor and flood control. The Mahaweli River Basin covers 10,000 sq. km (roughly 15% of Sri Lanka’s land area).

3.Pakistan built a network of river links as a part of Indus Treaty Works, which function as replacement links to irrigate those areas that were deprived of irrigation (after the partition), when three eastern rivers of Indus system (Sutlej, Ravi, and Beas) were allocated to India. Pakistan built ten links, six barrages, and two dams during the post-treaty period of 1960-1970. Most of the links built are unlined channels

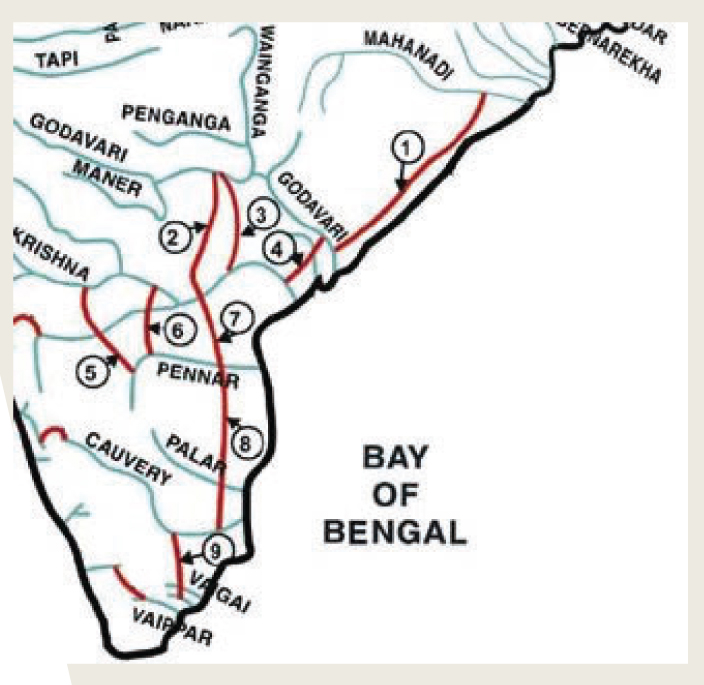

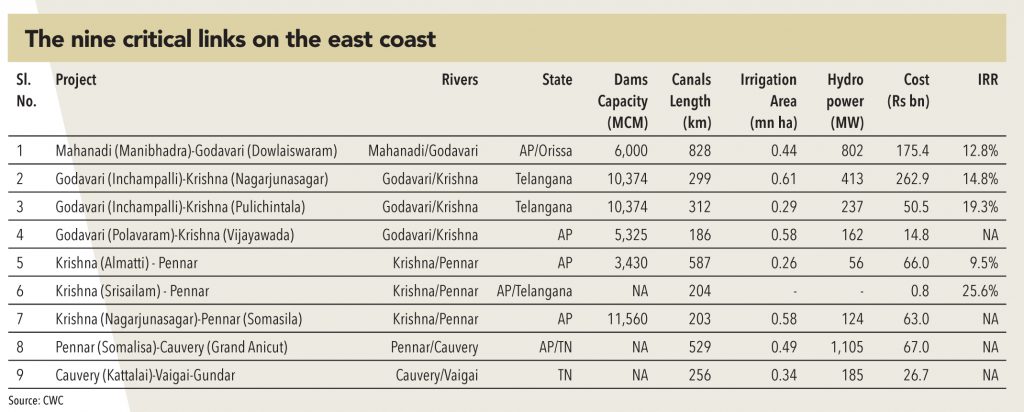

The peninsular component of the NRLP, apart from other small links, primarily focuses on connecting five large east-flowing rivers – Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, Pennar, and Cauvery. The objective of these nine links is to transfer the surplus waters of the Mahanadi and Godavari rivers to the deficit basins of Krishna, Pennar, Cauvery, and Vaigai.

These nine links envisage building multiple dams and over 3000km of canals over the five rivers. Interestingly, the rivers Mahanadi and Godavari already have some of the largest dams in India – Nagarjunsagar, Srisailam, Dowlaiswaram, and Prakasam. Despite these, the Mahanadi and Godavari rivers are flooded every year, leading to significant loss of life and property in Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana.

Through the three links between Mahanadi and Krishna, a major portion of the surplus quantity diverted is to be discharged into Nagarjunasagar reservoir for further diversion to water-deficit Pennar and Cauvery basins, after meeting the entire deficit of the Krishna basin. Since the water cannot be diverted to the Nagarjunasagar reservoir by gravity because of the topography), a series of pumping stations in four stages have been proposed along the canals, for lifting the water to a static head of about 107m.

However, these links will be the most difficult to execute. Three of the nine links do not envisage any reservoir construction, so there will be minimum displacement of PAP (project affected people) and hence minimum rehabilitation requirements. However, the other six links will add 47 BCM of reservoir capacity – which will lead to significant rehabilitation requirement. Also, the nine links are to be built by, and with the consensus of, seven states – which have historically been involved in multiple water-sharing disputes. Lastly, all of these states have a unique political landscape, dominated by local parties, which will be extremely difficult to bring together on a common platform. The only hope that one can have is that the ruling dispensations of these states realise the real, short- and long-term benefits of these projects and set aside their petty differences for the greater good. Perhaps too much to ask for in the current political environment !

After the advent of the NDA government at the centre in 2014, the NRLP started seeing some action. On 23rd September 2014, a ‘Special Committee for Inter-linking of Rivers’ was constituted. The first meeting of this committee was held on 17th October 2014, which was attended by state irrigation/water resources ministers along with the secretaries of various state governments. The meeting decided to constitute sub-committees to expedite objectives of the inter-linking of rivers. Subsequently, the committee met five times over the next one year to review the progress. On 14th April 2015, the Ministry of Water Resources constituted a ‘task force’ on inter-linking of rivers, comprising of experts and senior officials. Chaired by Mr B.N. Navalawala, the task force was to expedite the work on the inter-linking of rivers. Its key responsibilities were:

Two meetings of the task force were held in April 2015, and in November 2015. Over the last two years, the task force has managed to build consensus on multiple issues, and has made remarkable progress. DPRs for five of the 30 links are prepared and approved. Three of those five have also received environmental and forest clearances and project costs have been finalised. The three projects – Ken-Betwa, Par-Tapi-Narmada, and Damanganga-Binjal – are in late stages of approval and could see order award activity in late 2017. For the remaining 25 links, feasibility reports are being prepared or have been prepared.

Some of the key issues faced by the task force in some of the links are:

Himalayan component

1) The proposed storage and initial reaches of five water transfer links (Kosi-Mechi, Kosi-Ghagra, Gandak-Ganga, Ghagra-Yamuna and Sarda-Yamuna) fall in Nepal and that of Manas-Sankosh-Tista-Ganga and Jogighopa-Tista-Farakka fall in Bhutan. To carry out surveys and investigations in Nepal and Bhutan, permission of the respective countries is essential.

2) In 2004, the Bangladesh government had raised concerns about India’s NRLP, after which, in an meeting of the Indo-Bangladesh Joint River Commission held in Dhaka (19-21 September 2005), the Indian government had assured that it would not take any unilateral decision on the Himalayan component of the proposed NRLP that may affect Bangladesh.

Both these issues are being currently resolved with the help of Ministry of External Affairs (MEA).

Peninsular component

1) Parbati-Kalisindh-Chambal link: The government of MP wants to implement intra-state links instead of this inter-state link with Rajasthan.

2) Mahanadi-Godavari: The government of Odisha was not in favour of this link due to large submergence involved in Manibhadra dam. Based on the suggestions of the Government of Odisha’s Water Resources Department, the NWDA has prepared a preliminary revised proposal of the link with reduced submergence (submitted to Odisha government).

3) Bedti-Varda, Pamba-Achankovli-Vaippar, and Netravati-Hemavati links: The governments of Karnataka and Kerala have raised objections to these links.

The NWDA is trying to build consensus for objections, especially the first two links. The first link is important for providing relief to drought-affected areas of Rajasthan and MP and the second is the mother link of the nine link-system on the east coast.

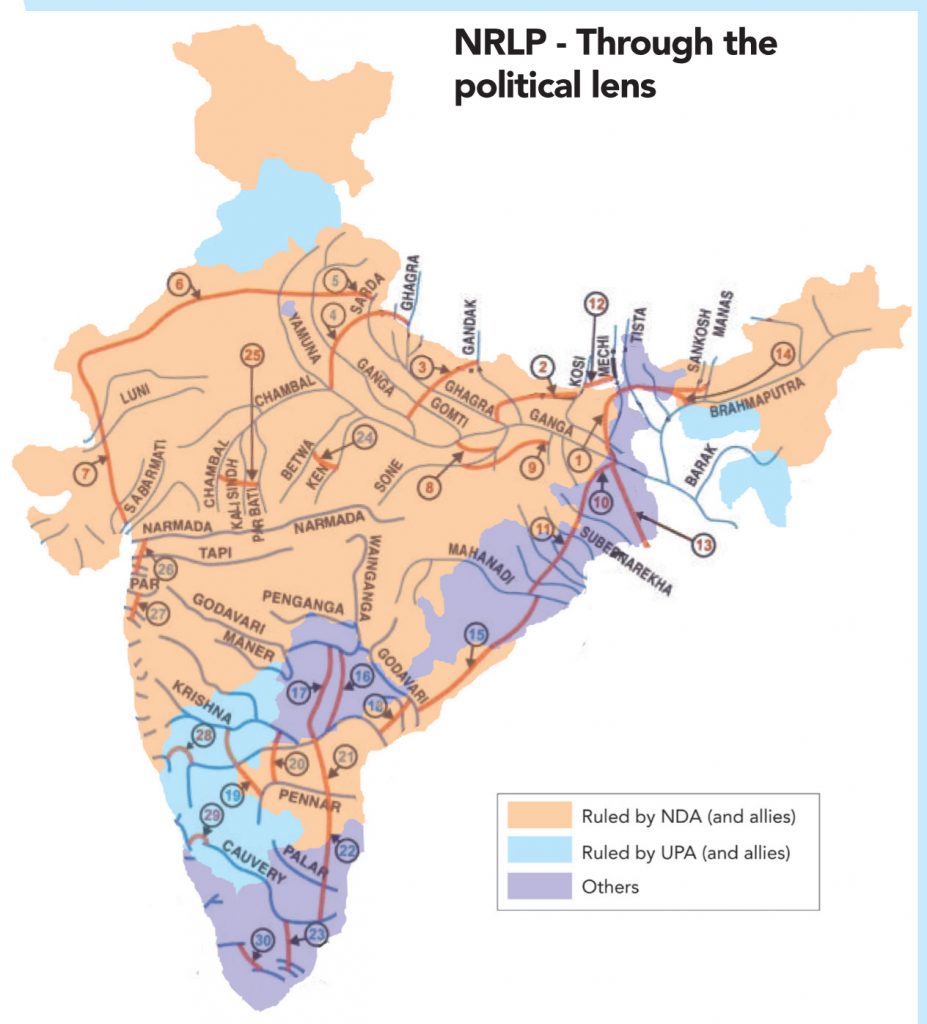

The biggest hurdle in executing a pan-India project of this nature is building a political consensus. Irrigation is a ‘state subject’ – the central government cannot execute such projects without the permission of the respective state governments. In fact, the link projects have to be executed by the various state governments under the ‘guidance and support’ of the centre. However, a fragmented mandate till 2014, and various states being under the rule of different political parties, meant that political consensus was impossible to build (it also appears that the UPA-1 and UPA-2 governments didn’t even try for a consensus).

After the NDA came to power at the centre in 2014 the political scenario has changed significantly, especially over the last two years. As many as 21 states went through legislative assembly elections over the last two years, and most saw a change in regime. As a result, the NDA rules as many as 18 out of India’s 29 states currently (in addition to being at the centre). The NRLP project is expected to receive a significant boost with the election results of the last two years. A prime example of this is the Ken-Betwa link – as long as Uttar Pradesh remained under the rule of a local party (SP), the project saw little progress (with the then UP government not ‘interested’ in the proposal). The other beneficiary state, Madhya Pradesh (NDA governed), was already on board. The NDA came to power in Uttar Pradesh in March 2017, and the project has seen rapid progress – the Ken-Betwa link is likely be the first one awarded under NRLP.

Currently, virtually the entire northern part of India is under NDA’s ‘control’, with the exception of Punjab and Himachal Pradesh. The Himalayan component of the NRLP is likely to see significant progress now, with political consensus looking easier to achieve. Most links in the Himalayan component need the approval of neighbouring countries (Nepal, Bhutan, and Myanmar) which the CWC is already actively working on. However, the southern peninsula still remains fragmented, with local parties ruling four of the five south-eastern states. The most important part of the project – the nine links that would connect the basins of the Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, and Cauvery rivers – still pose an ominous challenge, one that is unlikely to be resolved easily.

Currently, NDA rules as many as 18 out of India’s 29 states

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access