High capex CAGR of +7% over the past decade for the cement industry has already been a key concern. This is likely to halve over the next 3-4 years to just 3-4%. While a bulk of this capex will be going towards grinding and logistics (not capacity addition), most of it will incorporate the latest technology and full support systems of newer inventions such as waste heat recovery systems and ability to use alternate fuels with full supporting infrastructure to tackle such resources.

Most of the capex is on a fast track – the internal targets of project teams are much ahead of the official targets announced by manufacturers. This means that the compulsion for individual manufacturers to move towards better efficiencies in order to maintain their competitive edge is only going to increase, as those who don’t will lag behind.

This capex is not likely to generate too much incremental savings, though few companies may gain marginally as they address structural operational bottlenecks. Overall, the sector will have to heave the burden of higher and consistent compliance. In fact, even now, a lot of ancillary capex initiated by the sector is to ensure that it remains more complaint than before.

Given that the average size of kilns now being set-up is nearly twice what it was earlier – at 7,000 tonnes per day vs. an average of 3,500 tonnes per day earlier, the sector will feel a natural need to invest heavily in building more clinker and cement silos. It may also feel the need to have more packers, given that most of the demand for cement in India continues to be in the form of bagged cement. As demand for cement remains seasonal, absence of such capex will mean a natural pressure on the sector to push volumes during off seasons, as the infrastructure currently present at all sites may not be sufficient to hold the inventories at plants and absorb market demand fluctuations.

As it is costly to stop and restart kilns, the sector will feel the need, soon, to naturally adjust to market demand fluctuations. This means that the sector’s capex spends will rise substantially – not by choice, but by force. Investments in developing better infrastructure for railway and port connectivity (mainly for coastal plants) will be an added capex burden. Road travel beyond a particular lead distance becomes unfeasible, so for individual manufacturers who want to target ‘long lead’ markets, such investments are a necessity. A lot of this capex has already begun – select manufacturers have quietly started investing in such initiatives.

Nearly 40%+ of the sector’s cost is for distribution and marketing. Players who move first to optimise this, not just production efficiencies, will be long-term winners. Not many have focussed on improving supply-chain management and addressing its inefficiencies yet. With limited scope for improvement in margins through production-level efficiency and a largely compliance-oriented capex, manufacturers will turn to the supply-chain for relieving stressed operating margins – a sort of automatic push in this direction. This should result in a more sustainable and balanced operating margin structure for the sector in the long run.

Here are some improvements that have already been rolled out to plug supply-chain inefficiencies: Transparent and strict loading norms and distribution practices and stringent implementation of structural regulations such as GST and E-way bill. However, many legacy (unethical) practices still exist in the supply-chain and distributor network (such as ‘back and forward loading’ or material pilferage), which allow moneymaking opportunities for almost everybody in the chain, but lead to undercutting of cement prices.

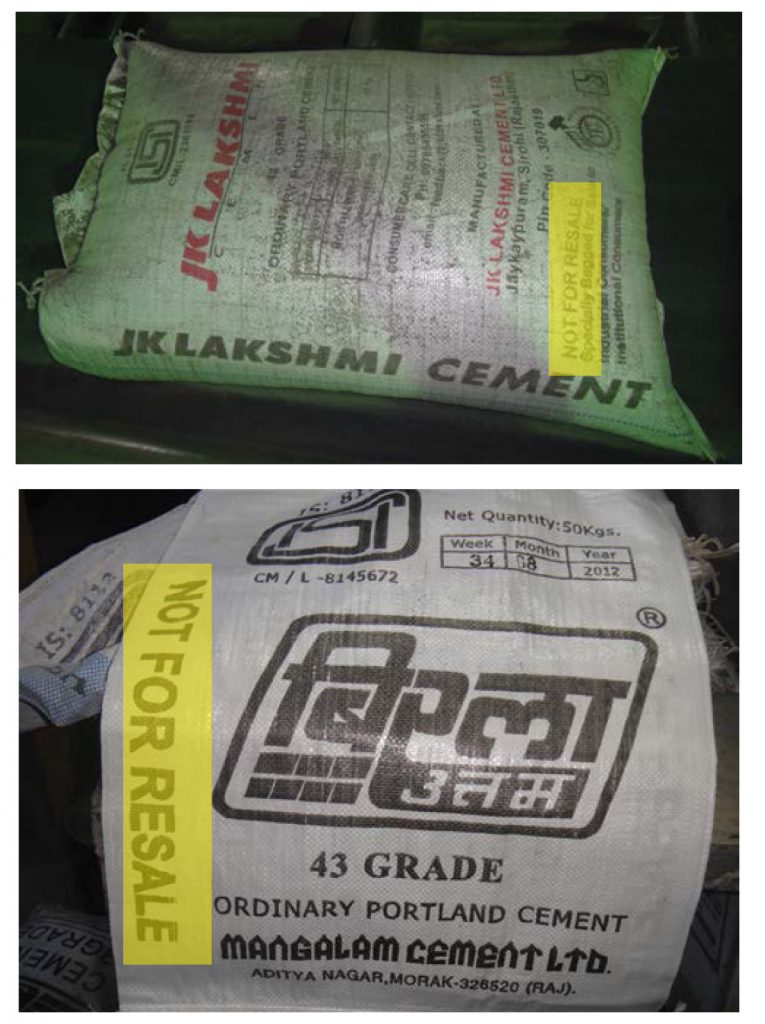

Players who plug these leakages first will have an early mover advantage. In a recent media article Mr Shailendra Chouksey, Whole-time Director at JK Lakshmi Cement was quoted as saying: “On our wide distribution network handling volumes, around 8 lakh (800,000) tonnes/month pilferage, and back/forward loading are some of the key operational challenges that we face. We believe that gaining better visibility into our vast network of multiple plants and about 10,000 destinations will help us control pilferage, optimize capacity, and eventually help us deliver a superior customer experience.

Back-loading and forward-loading pilferages

The differential between the distribution chain’s actual spends and real cash flows become its incremental earnings. These earnings becomes the cushion for the network to offer incremental discounts, buffer their ability to negotiate on volumes, and make better counter offers to customers – but they ultimately damage cement prices. Here are a few examples of how this happens:

• Case 1 (back loading): Material is sold on CIF (cost + insurance + freight) basis to a destination via a stock-transfer mechanism through a depot. However, it is directly despatched to the customer instead. The customer is charged for both primary and secondary freights in this case (secondary freight includes charges from the depot to the customer, primary is from the plant to the depot). Here the secondary freight charges become the incremental earnings for the entire distribution chain.

• Case 2 (back loading): Material is billed for long lead distances, but sold at shorter lead distances. In this, the freight charged and actual freight are materially different – and the difference becomes the earnings for the entire distribution chain.

• Case 3 (forward loading): This is vice-versa. The price of cement in State A is Rs 250 and State B it is Rs 350. The distribution chain will initially bill the material within State A and then re-route it to State B. While the chain will spend additional money (IGST payment, freight) but incremental gains from selling the material in State B are far higher.

In the market that it is practiced in, pilferage hits the efficacy and stability of pricing, which in turn makes cement prices volatile in the region. Cement is a fast-moving commodity, so it is easy for the supply-chain to indulge in these practices.

Ex-factory billing is also not fool proof, though still safer

Lately, many cement manufacturers have said that they will look at increasing ‘ex-factory’ billing to ensure better realisations and stable pricing. This type of billing can be good if manufacturers adopt standard price for all their despatches. However, what really happens is that the distribution chain negotiates the price based on the customer’s profile, location, and terms of credit (if applicable) and all manufacturers tend to provide different ex-factory prices based on these qualitative parameters. Therefore, even if billings are done ex-factory, it is not yet a foolproof mechanism to address pilferage, though it is safer.

Moving non-trade cement to trade – rare, but very damaging to prices

Cement sales are classified as either trade sales or non-trade sales. In almost all cases, the first-stage distribution partner is responsible for both types of sales. Non-trade (bulk, institutional) prices are usually lower than trade (retail) prices. Theoretically, trade sales should go to retail buyers and non-trade to institutional, but many small builders and RMX players are generally supplied through the trade channel too. The price gap between trade and non-trade (which is ideally Rs 15-25/bag but sometimes rises to Rs 50-60/bag) is very crucial for stability of cement prices.

Trade sales

• Customers are generally retail – individuals, small builders, RMX players.

• Material flows from the factory to the distributor – then from the distributor to retail counters or directly to customers.

• Credit risk is less as turnaround time to realise payment from customers ranges from immediate to less than a month.

• Prices of cement are higher than in non-trade; trade sales are always more beneficial to a company and the distribution channel.

• Preference of any cement manufacturer is to push more trade sales than non-trade.

Non-trade sales

• Customers are mainly large contractors, real-estate developers, or government agencies.

• Chain of flow for sales is not very different from trade sales. The bigger difference is that the channel is more flat – except the first leg of distribution partner, the lower ends of the supply-chain are not generally not involved.

• In most cases in these types of sales, the distribution channel will underwrite the risk of their customers. In some cases the company may bear some of the credit risk. The supply exposure of a cement company to each distributor is a function of the working capital investment made by the distributor with the company (such as a security deposit). The offtake allowed is usually a function of such deposits (say 1x-2x, as per the terms of the agreement).

• In non-trade sales, the credit cycle is much higher than trade – 1-3 months. If a customer delays payment, the capital of the distributor is blocked, and the company may not increase its supplies to such a distributor as its credit-risk increases. In tight liquidity conditions, such distributors face outstanding payments and rising risk of default.

Recently a third type of sales concept has emerged to facilitate better supply-chain, especially in the distribution of non-trade (bulk) segment.

Key accounts or exclusive accounts sales

• Key accounts or exclusive accounts usually belong to large corporates or builders with good credit rating and a largely on-time payment record.

• For such accounts, cement manufacturers do not mind taking the credit risk by supplying directly, even as they continue to pay the network partners basic commissions for handling, loading, and unloading.

In tough market conditions, the challenge for the supply-chain is to keep up liquidity levels, so that future orders are not delayed. For this, the supply-chain tends to divert some non-trade supply to trade since the former is at a discount. In this sequence of events, the customer will get the non-trade cement in the trade segment at a discounted price. This gives the network an opportunity to discount cement prices in trade (up to the extent of the prevailing gap between trade and non-trade cement prices). This improves the supply-chain’s liquidity flow – not surprisingly, the trade network welcomes cement at a discount. However, this practice damages prevailing trade prices. Trade sales is the lifeline for cash flow in the sector and this practice upsets the balance.

In unfavourable market conditions when the liquidity is tight and the price gap between trade and non-trade increases, diverting non-trade cement to the trade segment also increases. This happens because the supply-chain has to ensure that liquidity crisis eases and the order flow continues. Diverting material leads to quicker payments, which helps solve its liquidity crisis, at least temporarily. Recently, most of the demand delta has come from infrastructure demand. With rising orders from bulk (non-trade) of late, the risk of these malpractices have increased, as the general liquidity conditions are not too favourable.

All manufacturers said they have adopted a ‘zero-tolerance policy’ for such divergence and no non-trade cement can move to the trade segment; if anyone is caught, they say, stern action is taken – such as dismissing the sales officer in charge and cancelling the dealership. While this may not be entirely true, this malpractice has become rare now, if not fully absent.

One solution that some cement manufacturers are working towards is doing away with non-trade supplies and only keeping trade supplies – i.e., supplying both through trade. These are largely internal targets or aims for now, but are not unachievable. If this happens, the sector will be reborn as far as supply-chain dynamics go. That supply-chain malpractices are now seriously hurting manufacturers badly is evident from JK Lakshmi Cement’s management commentary in a recent media article. The sector is cleaning up the system to achieve stable cement prices, which will also improve the earnings potential of cement manufacturers. The delta is huge – even a Rs 10/bag sustainable improvement in prices (which is just the minimum potential) will lead to an additional EBITDA/tonne of over Rs 140 (adjusted for taxes).

The industry is going for innovation to address supply-chain issues

Recently, few manufacturers started intermittently printing truck numbers on cement bags so that they are reconcilable and traceable at destinations. Few others have started printing district codes on bags and some are printing more precise production data on the bags. Printing additional data on a cement bag costs 7-8 paisa per alphabet, so for a four digit truck number, the cost is a quarter of rupee. Extremely cost-conscious producers have opted for GPS in their captive trucks to ensure real-time movement can be tracked. For hired trucks, manufacturers are making it compulsory for transporters to install GPS tracking and are ready to pay monthly charges for this. Some are even funding the initial capital costs!

Nevertheless, outsmarting the great Indian jugaad tendency is a big ask. An example – as the transport truck starts moving, a small scooter will follow it. After a certain distance, the truck’s driver will remove the GPS chip and hand it to the scooter driver who will ride until the official destination (scooters and trucks travel at similar speeds). On record, it would appear that the truck has travelled the official distance but in reality, the material is being back loaded.

With practices becoming stricter, the cost of malpractices will increase and breaches will become more and more rare as they become unsustainable. For now, none of the mechanisms adopted by manufacturers are 100% fool proof, but they are definitely streamlining supply-chain practices which will lead to sustainable betterment of the sector’s long-term dynamics. In general, the big brother is watching message has permeated – the distribution chain is aware that many of the malpractices are traceable, so directionally there is tendency towards minimisation of such practices.

The cement sector is largely organised, but allied building materials sectors such as sand, stones, and bricks still operate in unorganised formats in many states. Though these sectors are moving towards being organised, the progress is slow. In many cases, cement shares distributors and channels with these sectors. As products of these unorganised sectors are billed in cash in many instances, a window of opportunity opens for the channel to increase its margins, which ultimately hurts cement prices.

An example: Selling of official bills – an established mechanism for the channel to make money

• Many consumers purchase building materials in cash and do not take bills from retail stores, which leads to an inventory build-up in the books of the retailer.

• A real-estate developer or government contractor will purchase such bills from retailers for as low as Rs 2 per bag, while showing the purchase cost in their at about Rs 300 per bag (or whatever the prevailing cement price is). This way, contractors/real-estate developers submit bloated bills to government agencies or show subdued margins officially and make a case to customers for higher rates. The channel earns Rs 2 per bag for doing nothing other than selling the invoice. It becomes a win-win situation for both – contractor / the real-estate developer and the channel.

• These incremental earnings add to the channel’s cushion to discount cement prices and the vicious cycle begins.

A key reason why the channel veers towards unethical trade practices is thin margins. Except the ones in south and west India, cement channels are not incentivised for increasing prices. In the south and west, the channel genuinely attempts to take care of pricing because in these regions incentives are ad-valorem, not fixed commissions per bag. This is the reason cement prices rarely cross Rs 300 per bag in north India, while they routinely touch Rs 350-400 per bag in the south. The channel’s earnings potential in the south and west improves if prices are better.

If this structure is standardised across regions, most malpractices will automatically stop as the channel’s earnings from the cement business itself would be decent enough, leading to lower motivation towards unethical procedures. From the ground it appears that few manufacturers recognise this and are working towards a more ‘inclusive’ and a standardised approach for the channel across regions.

However, recently, cement prices in the south and west were also low. How?

• Huge inter-state transfer movements from few excess-capacity southern states to other adjoining states because price gap was too lucrative.

• Cement manufacturers in excess capacity states attempted to increase volumes by supplying to other neighbouring states and capitalise on volumes.

Why did the channel accept these volumes from other states if it would hurt their business interests and incentives?

• At times, the volume push from large-capacity states can be so phenomenal that the channel’s absolute incentives are almost the same – whether it chooses to go along with volumes or prices.

• The channel and number of players in south India are much larger than any other region, so following basic business ethics for cement manufacturers is more important.

• Many trusted or exclusive channel partners were disappointed by the volume push from large-capacity states, but ‘natural forces’ that come from such a volume push made them accept lower prices.

• Large capacity regions will always face such risk, but the important point is that the long-term sustainability of cement prices in regions with a more trusted channel is higher than in a region in which the channel does not care about pricing.

Bandwidths of manufacturers differ – this matters when incentivising end-users

It is not just the supply-chain, but also about incentivising end-users such as architects, masons, and consumers.

Though infrastructure has contributed significantly to the revival of cement demand, individual house builders (IHB) remains a key demand segment that can give the sector its earnings delta as price premiums here differ substantially. Cement brand needs to have good recall by architects, masons, and consumers. For this, companies organise local melas (fairs) and award functions to appreciate the efforts of architects, masons, and to reward end-users. Many manufacturers also run incentive schemes where they insert coupons or tags in cement bags, which consumers can then exchange for some rewards such as recreational activities or gifts.

All manufacturers have different methods and terms of incentivising end-users and channel partners. Pan-India majors and large multi-regional leaders generally stand out.

Here is an example of such methods – The sales heads of a region or district visit the house of the Sarpanchs (heads) of villages and give them a small token of goodwill – such as a pressure cooker or a mobile phone. They stay to have a cup of tea and a casual chat at their houses. While these heads will not usually directly discuss cement consumption at the Sarpanchs’ village, to reciprocate their goodwill gesture, Sarpanchs spread the word in their villages about that particular cement brand and push people to buy it while building houses. For the cement company, the cost of such ‘gestures’ is negligible, but for the Sarpanchs it is a matter of pride that a local region or district head visited their house, gave gifts, and more importantly, interacted with them socially. In such initiatives, pan-India majors have a different bandwidth because of their more ‘intense’ spread across states, higher number of sales officers, and more network points. The financial strength of a company will matter, as such initiatives ultimately depend on the budget.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access