Towards efficiency and environment preservation

Detergents that consume less water and provide convenience and superior wash with minimal damage to the environment will see maximum off-take. Liquid detergents that do not leave any residue behind in the machine are best suited for the environment, but its packaging formats (plastic bottles) damage the environment. Consumer durable companies (washing machines) that are working on technology that helps to reduce water usage will be at the forefront.

Pods and tablets could be the next leg of premiumisation

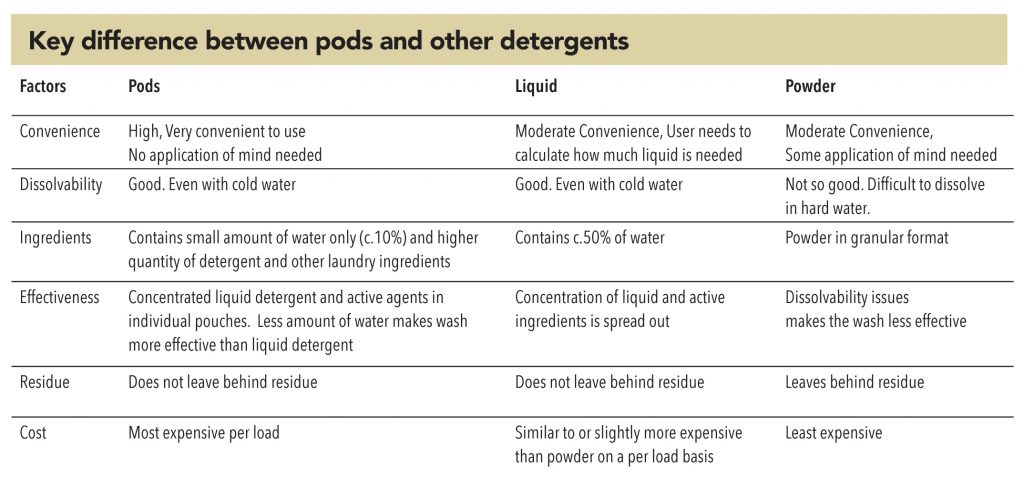

Detergent pods or tablets are single-sized dissolvable pouches that contains highly concentrated liquid detergent, softener, and other laundry products inside a single pouch. The pods are easy to use – they just need to be chucked directly inside the machine drum and are premeasured, which helps customers to avoid unnecessary wastage.

Consumer durables company IFB derives 10% of its revenue from consumables, mainly detergents. Tushar Singh is a sales person at IFB Point (the company’s owned retail outlets, which provide products and services across a range of categories), which also keeps its own laundry products, including detergent pods. He explained why pods are such a simple solution. “With laundry pods, customers need not apply their mind as to what quantum of detergent or softener or conditioner needs to be put in to the wash cycle. They just have to put one or two pods depending on the quantum of clothes,” he said.

Detergent pods were an instant success when they were first launched in 2012 by Tide. Currently, detergent pods constitute c.15% of the laundry market (value) in the US.

Water is the new gold: Are waterless machines almost here?

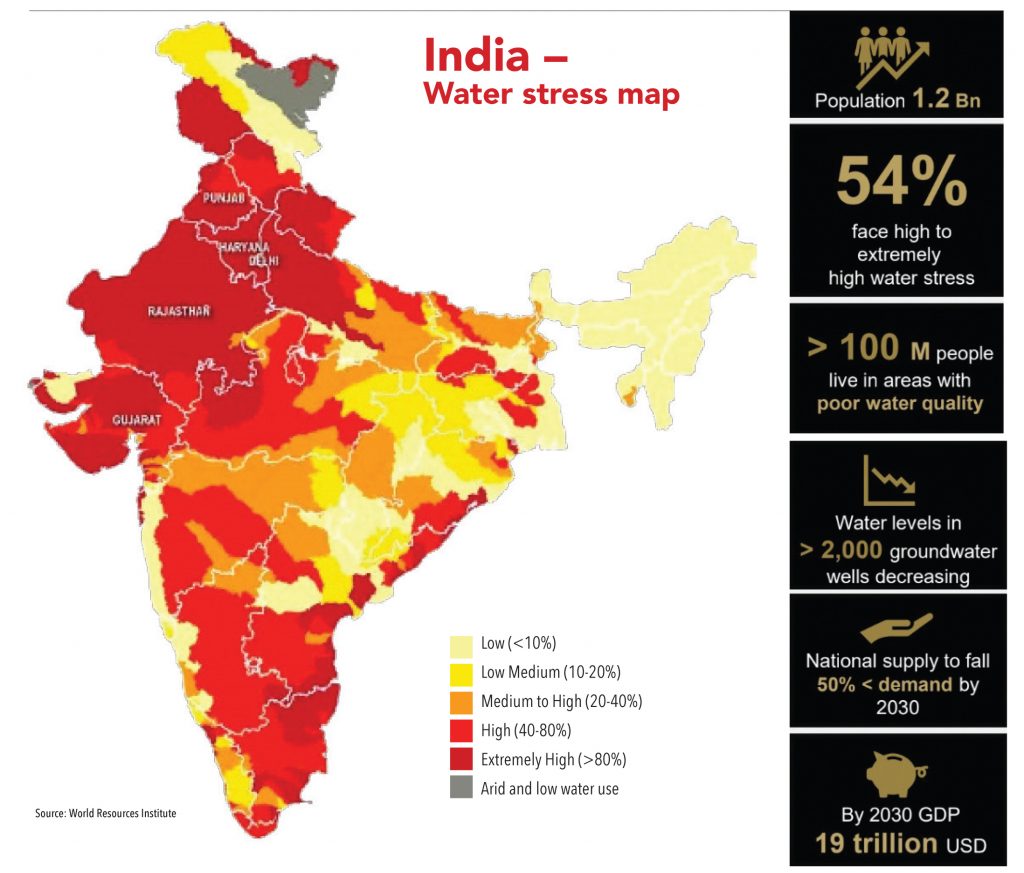

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), by 2025, over half of the world’s population is expected to be living in water-stressed areas. Availability of fresh water is expected to be challenging in the future, driven by continued rise in world population. This, coupled with a drastic change in global climate has brought on droughts and floods. Statistics show that water usage has been increasing 1% a year on an average while availability has been falling every year.

Xeros Ltd. has invented a washing machine called Hydrofinity Xeros XOrbs washing system in 2014, which uses 80-90% less water and 50% less electricity compared to washing machines available in the market currently. It uses a technology that cleans laundry using re-usable nylon polymer beads called “XOrbs” – which are super absorbent. It claims that XOrbs absorbs dirt and stains without damaging the clothes and prevents fading and linting.

How does Xeros’ XOrb washing system work?

When a wash cycle starts, XOrbs are added in the laundry compartment to mix with the fabrics and a small amount of water. The water itself is sprayed in, rather than poured, to improve efficiency. XOrbs (re-usable nylon polymer beads) gently massage garments, loosening dirt and stains. XOrbs then expand slightly, creating microscopic cavities that absorb and trap stains, carrying them away from fabrics, in a small amount of cold water. When the wash cycle is complete, the XOrbs automatically return to a holding area inside the machine and are ready to be used again for the next wash. Xeros claims XOrbs can be used up to thousand washes and are collected by the company’s technicians for recycling in exchange for new ones.

So far, this technology has been restricted to B2B units (hotels and laundries) and Xeros expects that its new technology will be made available for consumer washing machines as early as 2020. It plans to partner with major appliance companies, which will help bring down the cost per unit and drive faster adoption. Though this technology is at the developing stage and initial cost of the machine could be expensive, over a longer period, this could be threat to detergent companies and premiumisation.

Washing machine OEM players will have to evolve as total solutions providers

Consumer durable companies will have to evolve as total solutions providers rather than selling plain-vanilla washing machines, collaborating with FMCG companies by giving free detergent when customers purchase washing machines. OEM companies will have to extend their roles beyond just selling washing machine – they will have to help customers with better-formulated products that provide a better quality wash.

Although most washing-machine OEMs offer two-year warranties on their machines, their technicians rarely visit customers’ homes (only if there is breakdown). IFB Industries has taken a different approach. Its technicians visit customers (without being distress-called) just to service the machines every six months. This, it believes, (1) enables the company to up-sell its detergents portfolio (technicians earn 5% commission on every pack of IFB detergent sold), (2) significantly enhances customer relationships, as customers feels special, and (3) motivates technicians to stay with the company longer since they have an opportunity to earn higher income.

Mehul Bhatia, a resident of Borivali said that he prefers using IFB’s own liquids detergent despite the product being priced at a 40-50% premium to Surf Excel liquid detergent. He says that while he had to use 2 litres of Surf Excel Matic liquid for desired results, he has to use only a litre of IFB’s liquid – given the latter’s superior product quality, which reduces his effective cost.

The CEO of a leading front-load washing machine company said that his company wanted to become total solution provider in the longer run. “We are not merely interested in selling only washing machines. c.10% of our business already comes from selling detergents, which we are currently importing – and we plan to manufacture these in-house once we reach the desired scale.”

Innovation will be a key element

Rin’s ‘Save Water’ campaign proved to be effective. In 2017, HUL re-launched its Rin detergent bar with the proposition of Smart Foam Technology, which, according to company, saves up to two buckets of water in every wash cycle. Normally, while doing laundry, rinsing-out clothes consumes 70% of the water, as people tend to keep on rinsing until there is no visible foam on clothes. HUL’s technology does not allow foam to stick to clothes, which results in less water while rinsing.

Millennial are looking for environment friendly products

Water pollution caused by laundry detergent is a big concern in the global context. Many laundry detergents contain 35-70% phosphate salts, which make detergent more efficient by helping to soften water and remove stains, but these phosphate particles remain in wastewater (cannot be eliminated) and make their way to natural water bodies, producing algae that are harmful for the environment and aquatic animals.

With stricter rules by various governments and organisations globally to save water bodies, most modern and premium laundry detergents will have to be compliant with environment and social norms and they will have to launch products that minimise damage to the environment.

Natural products could be a possible solution

Over centuries, reetha (soap nuts) has been used as a natural laundry detergent. Soap nuts are great surfactants – when in contact with water they release suds that can do wash clothes naturally and in an environment friendly manner. With this in mind, Manas Nanda founded BubblenutWash in 2016. It is a Bengaluru-based startup that uses reetha to produce laundry detergents, dish-wash, floor cleaners, hand-wash and other washing products – primarily targeted at urban customers. It is different from modern detergents, as it is 100% chemical free detergent. Bubblenut products are available in Pune, Hyderabad, Chennai, Mumbai, and Delhi and currently have 10,000 plus customers.

Laundromats: Are these a long-term threat to premium detergents?

Many entrepreneurs, especially those involved in start-ups, are launching laundromats – self-service coin-wash or professionally operated laundry services. These are fairly common in western countries such as the UK, the US, and Canada. Indian start-ups such as Uclean and Washiteria are providing full services – from washing to ironing – but the charges are on the expensive side (Rs 25-30 per cloth for washing and ironing). However, these costs could fall as technology improves and scale increases. Increasing proportion of DINK (double income no kids) and nuclear families in urban areas could contribute to this trend.

Though laundromats are at a nascent stage and a largely urban phenomena, these could pose substantial risk to premiumisation in the future. If they become popular, adoption of washing machines could fall, impacting sales of premium detergents. This is because laundromats use their own captive detergents instead of buying products from branded national players.

However, it is not going to be an easy journey for laundromats. Indians customers are not willing to give clothes that are meant for daily use (worn inside their homes) to laundromats – they are choosy about which ones to give. This means that they need to have washing machines at home and run a cycle in any case. As a result, most customers end up cleaning clothes themselves.

Even the dhobis have shifted to premium detergents and washing machines

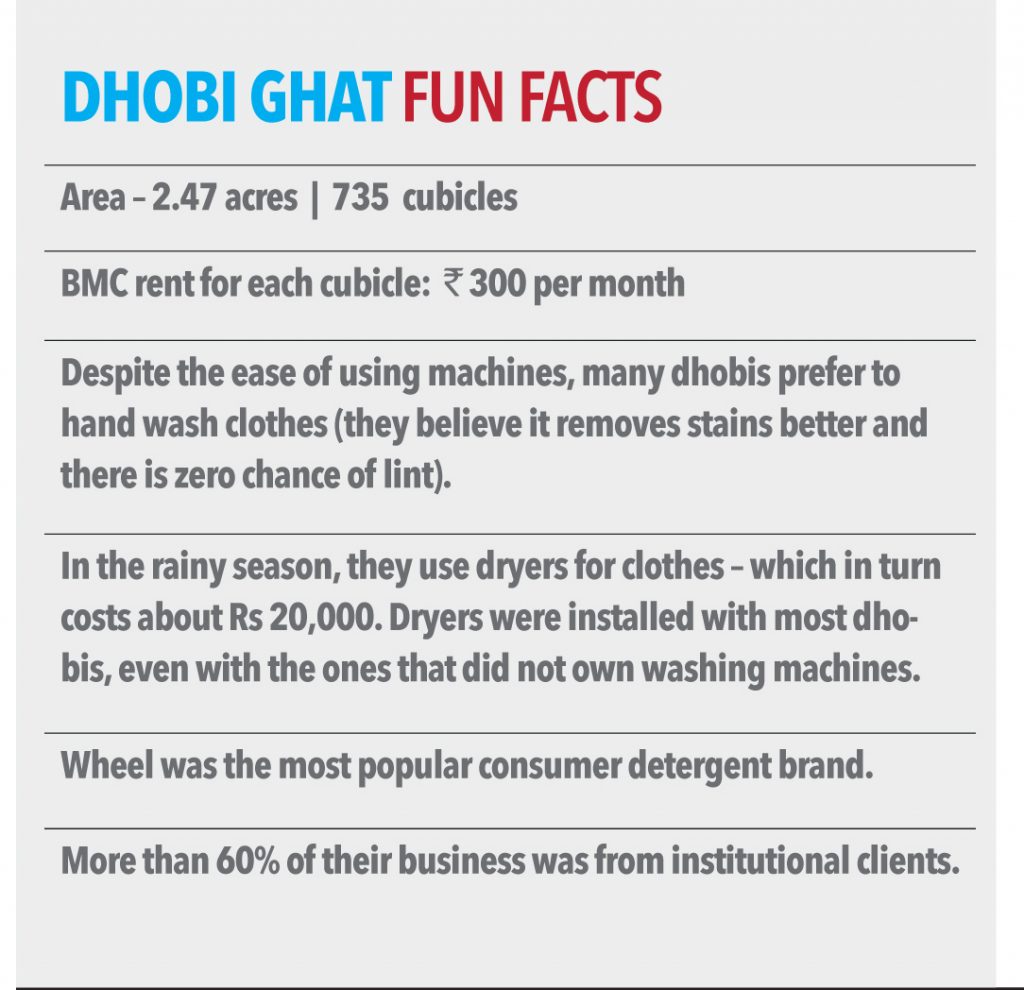

Dhobi Ghat was built in 1890 under the British Raj to wash their clothes and make their life easier. The uneven narrow lanes of the ghat are filled with rows and rows of wash-pens each fitted with flogging stones that have been there since their inception and used to hand wash clothes. However, modernisation has crept in among these ancient stones as well. Some of the wealthier washers at the ghat have now purchased machines due to lower availability of manpower and higher scale of operations.

Raj Nirmal, an owner of a cubicle in Dhobi Ghat said, “Ever since I have bought the machine, my business has grown considerably. Most of my business comes from institutional clients – garments dealers, neighbourhood laundries, wedding decorators and caterers, mid-sized hotels, and pubs. He said that his retail (individual) business has slowed in the past five years as most people in Mumbai use washing machines. “I am also seeing business from hotels and hospitals falling for the past few years, as some of them have set up their own captive laundries,” he added.Like Nirmal, most cubicle owners at the ghat said that faster adoption of washing machines in metro cities have led to a fall in the retail business. They mostly receive heavily stained clothes and those for dry cleaning – for which they use special local bleach and some liquid chemical to remove stains.

However, premiumisation has overtaken Dhobi Ghat too. Most of the washers were using branded detergents (Wheel or Tide), not local detergents. They said that both branded and local detergents cost the same. However, most did not use matics or liquid detergents for washing clothes.

In 2016, HUL launched India’s first urban-area-based water, hygiene, and sanitation community centre called Suvidha in Azad Nagar (Ghatkopar) – one of the largest slums in Mumbai. The purpose of this centre was to address the hygiene needs of people that reside in slums who might be facing challenges in doing daily household chores due to lack of infrastructure and facilities.

A visit to the Suvidha community centre revealed a laundry facility, drinking water machines, and bathing and toilet facilities – all at a low costs.

The centre comprised G+2 floors. On the ground floor was the laundry facility, water filter, and two toilets for specially-abled people. On the first and second floor there were 15 toilets and three bathing rooms (on each floor) – one floor each for men and women. Six employees were maintaining the facility and helping people to wash their clothes.

The laundry facility

• There were eight 7-kg fully-automatic front-load washing machines (Siemens) which used Surf Excel Matic powder and liquid to wash clothes.

• Customers had to put clothes in a bucket and leave the bucket for the helper (who generally took an hour to wash clothes).

• The centre charged Rs 55 per bucket and one bucket on an average carried five-six pairs of clothes. There was a monthly subscription available – Rs 650 per month, but customers could not do wash more than 15 buckets worth of clothes.

• The centre charged Rs 10 extra per bucket if customers wanted to use liquid detergents.

• On daily basis, 15-20 buckets (75-100 pairs of clothes) were washed, highlighting that the centre’s washing-machine capacity remains heavily underutilised. The pricing seemed expensive. But one of the employees said that most customers were blue-collar workers (with both spouses working) full time, leaving limited time for household chores.

Overall, the Suvidha facility seemed like a good initiative by HUL (works on a self-sustaining model) where members are provided with modern facilities and premium products at a reasonable cost. Through this initiative, HUL was encouraging consumption of premium detergents and also fulfilling its CSR objective.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access