‘Driver dila do yaar (please get me a driver)’ seems to be a common refrain from truck fleet operators. A scarcity of drivers is a major constraint that fleet operators across the regions are facing. This shortage is not only increasing the costs (higher salaries), but is also forcing operators to reinvent their business model by coming up with innovative compensation structures and changing the mix of their fleet. The problem is so severe that in the future (when growth picks up) driver shortages could actually spoil the party.

Factors leading to shortage of drivers

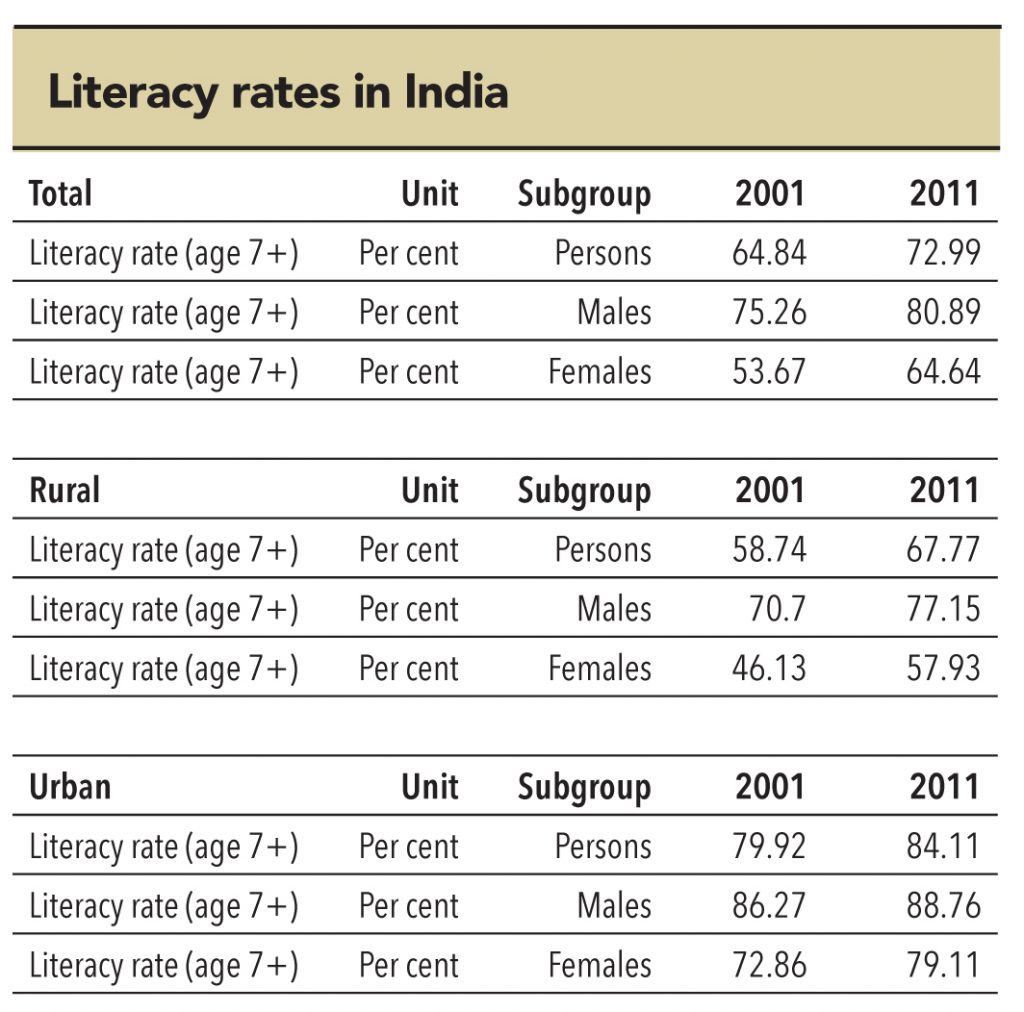

Improving education standards, rise in organised retail, and minimum age of employment are some of the factors driving the shortage. Improvement in overall education, higher aspirations, and expectations of a better standard of living are driving people to employment options that are considered more attractive than being a truck driver. As seen from the table, literacy rates have moved up to 73% in 2011 from 65% in 2001. The jump has been even sharper in rural areas, from where drivers were traditionally sourced. Literacy rate in rural areas have moved up from to 69% in 2011 from 59% in 2001.

In 2007, the Ministry of Road Transport made it mandatory for drivers carrying hazardous material to be educated up to the 10th grade and for drivers carrying other cargo to have a minimum qualification of 8th grade — this created more problems for the sector. A driver from Rajkot says, “Saheb license nahin milta hai (getting a license has become a herculean task)”. With that kind of education, people have other (easier) employment options (such as office peons, courier boys). Increasing penetration of organised retail has further accentuated the problem — people prefer to work in a retail chain than being a truck driver.

Despite the fact that this profession pays well, people are reluctant to take it up. A fleet operator plying hired vehicles across India highlighted this (the reluctance to become truck drivers) as a reason for a good number of second-hand vehicles being up for sale, but without takers — in this industry,cleaners eventually graduate to becoming truck drivers, and truck drivers eventually become small truck owners and more often than not, they start by buying second-hand trucks.

Monthly gross earnings (before trip expenses of Rs 5,000-10,000) for a driver could range between Rs 30,000-40,000 vs. Rs 10,000-15,000 for a job in organised retail.

The main reason behind the reluctance to become a truck driver is the quality of life and compromised family time. The Treasurer of the South India Bulk LPG Tanker-Owner Association says, “People prefer driving tankers despite lower income as they are able to visit the family every week unlike trailer drivers who come home after 20-30 days.” The current generation is wary of taking up driving trucks as a profession because of the hardships and the risks involved. Older truck drivers are reluctant to let their children enter into this profession due to several occupational hazards, one of which is the increasing rate of HIV prevalence among truckers. According to the surveillance report of HIV among different risk groups in 2010-11, the prevalence among truckers is 2.59%, which is 10 times higher than national prevalence among the adult population of India (0.27%) (Source: MOU signed in June 2014 between Ministry of Road Transport & Highways and Department of AIDS Control).

Flouting of norms to mitigate the shortages

In the past, ‘cleaners’ were hired (who are assistants to the truck driver and even take over in patches when the driver tires out) with the understanding that they would eventually graduate to becoming a full-fledged truck driver. This practice is facing issues with the mandated age norms — many states are against hiring people below 18 years of age and have issued notifications after CY12 revising the minimum age limit to 18 years (from the earlier 14 years). The constitution of India still has a minimum age limit of 14 years, except for some industries.

While truckers still follow the practice, the prevalence has come down, leading to availability issues. This, along with higher compensation,is leading to many freight carriers flouting norms and making do with a single-driver for an interstate journey vs. the national permit requirement of two drivers per vehicle. A government crackdown on this will further aggravate the situation. Operators are running the vehicles with one driver because quality of commercial vehicles has improved over the years. New global entrants gain an edge over the domestic CV players, given superior technology. However, lower capacities for the global majors and higher product offerings by incumbents will limit the impact.

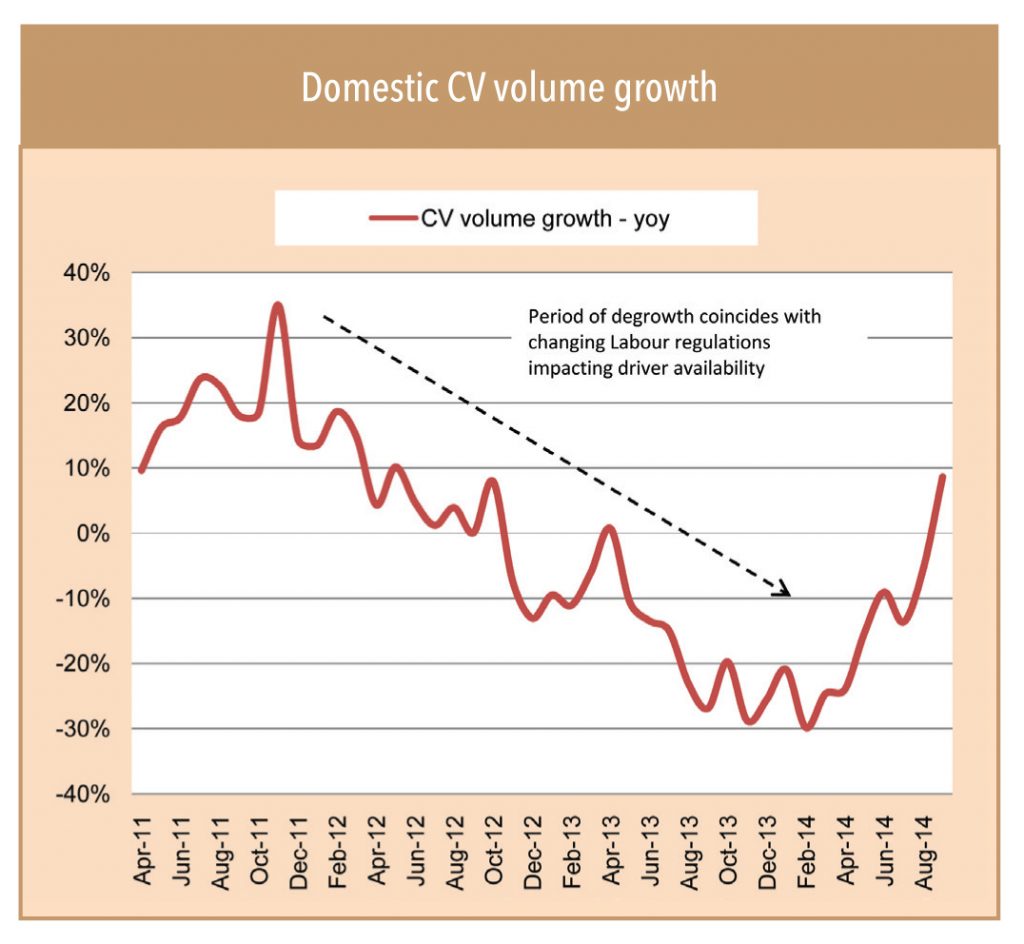

While the availability of drivers due to changing regulations has been an issue for a few years now, the impact was not felt severely because it coincided with a fall in the CV industry. CV volumes peaked towards the end of FY12 and started declining from FY13. However, this (driver shortage) can play spoilsport to the CV volume growth when the economy improves.

Driver shortages is a well-acknowledged problem

OEM manufacturers are aware of this problem for a while now. Mr Ravindra Pisharody, Executive Director (Commercial Vehicles) at Tata Motors said in a media report in February 2011 that driver shortages could slow growth in commercial vehicle sales to 20%from 25%.

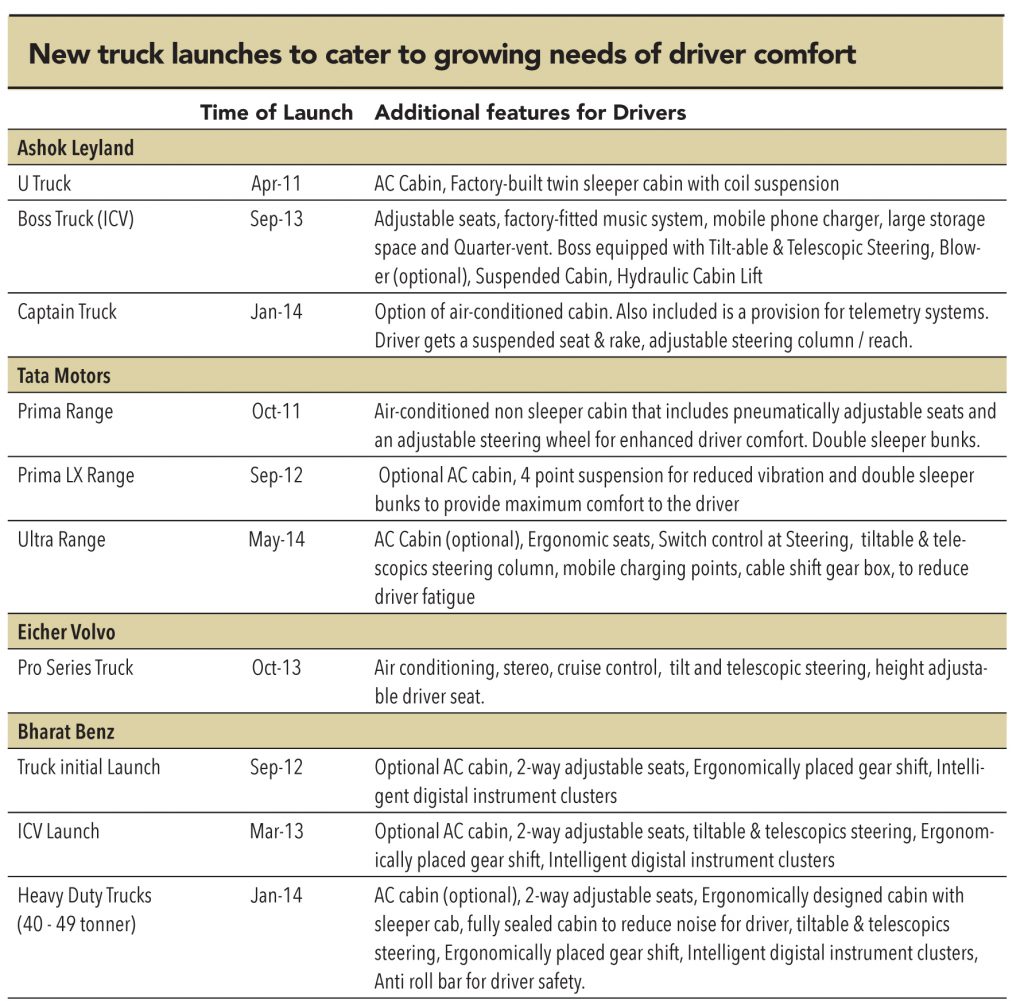

CV manufacturers have taken various initiatives to address the problem, ranging from introducing various driver-friendly trucks with better driving conditions to undertaking various driver-training programmes. They launched many truck ranges keeping in mind driver comfort.

Driver training institutes – is it really helping?

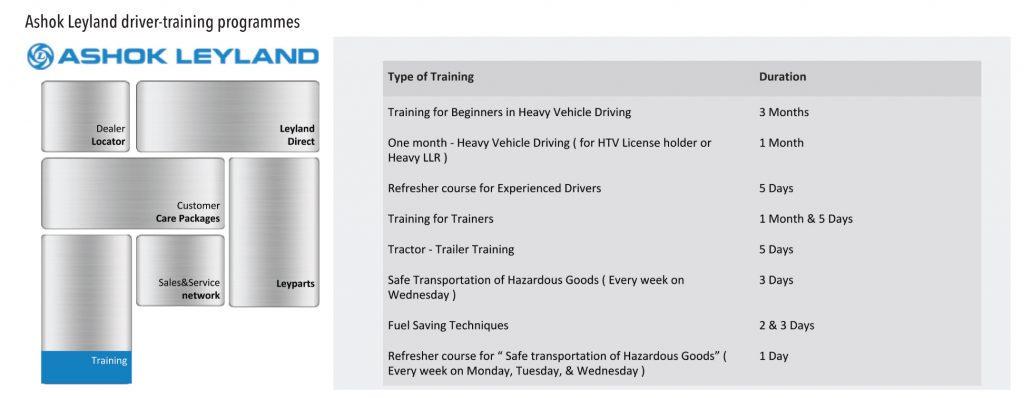

Ashok Leyland has opened or is in the process of opening 8 driver-training institutes at Nammakal,Burari, Kaithal, Chindwara, Bhubaneswar, Rajsamand, Bangalore and Dharwad. Tata Motors has also set up or is in the process of setting up such institutes in Punjab, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Assam, Nagaland, Bangaladesh and SriLanka. Volvo trains 2 drivers for every truck sold in India in addition to training drivers on a standalone basis.

A manager at one of the oldest driver-training institutes put a very different spin on the intent of CV manufacturers in setting up such institutes in India. His view is that this is only a CSR activity for companies and not really designed to benefit anybody.

However, to be fair to corporates running such programs, low enrolments are because of the reluctance on the part of the drivers, who prefer the traditional route of becoming a cleaner and then graduating to becoming a driver.

Training charges per driver are significantly lower than the training costs. CV companies charge Rs 4,000-5,000 (for the three-month course where a driver is trained one hour daily), while the total training cost is actually Rs 30,000-40,000. Driver enrolments continue to be significantly lower despite the low charges. A fleet operator said, “Driver training institute koi kaam nahi aata. Waha log hi nahin jaate (training institutes are of no use, drivers don’t go there).”

As a result of low enrolments in company-run or privately-run driver-training institutes, the quality of drivers on road in India is quite poor. Most drivers are only dimly aware of even basic traffic rules and are sometimes completely unaware of safety procedures. A person involved in enrolling drivers into company-run training institutes had an interesting anecdote, “A company had once conducted a one-day workshop for drivers hired by a very large cement company. Of the 100 drivers attending the workshop, not even a single driver would have passed the license test had the norms been followed to the letter.”

Driver shortages escalating costs for operators and changing fleet mix

Driver shortages are leading to costs increases for fleet operators, as they are demanding higher salaries among other things. Traditionally, the drivers were happy to only discuss the salary before taking on an assignment — with the acute shortage, drivers are now in a position to discuss the type of vehicle and distance travelled. They do not want to drive second-hand vehicles and prefer new vehicles that provide more comforts and facilities. Fleet operators have had to change compensation structures — from fixed salary to a variable structure — to incentivise drivers. Namakkal Trailer Owner Association said that they are currently offering 13.5% of the total freight received to drivers. A driver in Gujarat said he is being paid on a per kilometre basis.

Through variable compensation structures, fleet operators are incentivising drivers to take on more long-distance journeys (vs. shorter distance freight) to maximise their earnings. This, along with the drivers’ increasingly strong and vociferous preferences for types of vehicle and distance travelled, will further evolve and harden the existing hub-and-spoke model; higher tonnage vehicles will be used for longer distances and LCVs will be used for local distribution. While this trend is already in place, it will emerge more sharply over the longer term. Once GST is introduced, this kind of a model will make even more sense; current logistics have to be planned considering various state tax structures.

OEMs revenue mix – new trends emerging; likely to change even further

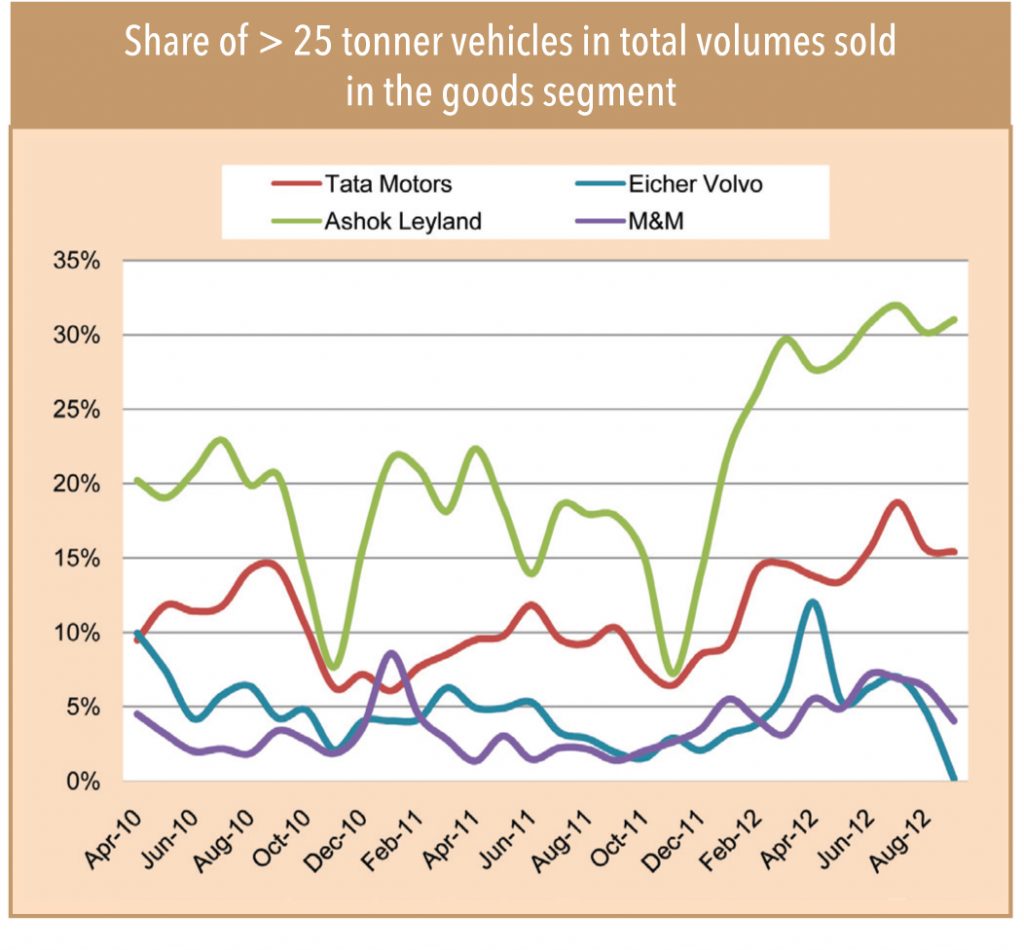

Driver preferences and the hub-and-spoke model will see the share of high-power higher-tonnage vehicles increase over the next few years. While this trend has already started emerging over the past couple of years since driver shortages became acute, the trend is likely to get more prevalent as driver availability deteriorates further. All major OEM producers have seen the share of 25-tonne-and-above vehicles (in terms of total volumes) increase over the last 2 years, while the share of below-25-tonne vehicles in the M&HCV category have either reduced or stayed flat.

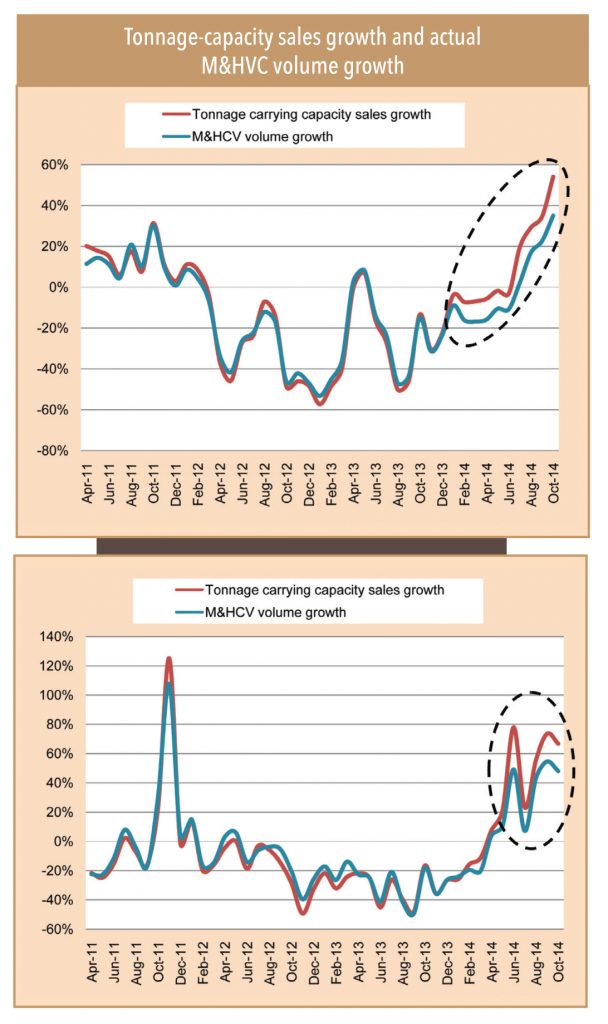

Tonnage sold will increase; volume growth will lag

Higher demand for 25-tonne-and-above vehicles will lead to superior growth for tonnage capacity sold; however, actual volume growth will lag.

Category-wise volume analysis for OEM’s M&HCV sales shows this trend emerging strongly in the past 6 months.

Conclusion: Driver availability issues will be a major impediment to CV industry growth going ahead as freight volumes pick up. This will also see a shift in product mix for various OEMs with higher-tonnage vehicles grabbing a larger share of incremental growth.

Subscribe to enjoy uninterrupted access